An interview with Ramón Ramírez

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 8 November 2022

MiniBio: Dr. Ramon Ramirez is the Coordinator of the Microscopy Centre at Universidad Mayor in Santiago de Chile, and a leading member at LiSIUM (the light sheet imaging centre). He did his early career in Chile, at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso where he studied a BSc in Biology. He later went to Madrid to study a MSc in Scientific Photography under the mentorship of Dr. Luis Monje. He did his PhD fully focusing on imaging viruses, with Dr. Sergio Marchel, at Universidad de Chile. Ramon is fascinated by light sheet imaging and hopes to bring this cutting edge technology to a larger scale in Chile. Moreover, Ramon is one of the founding members of SEECA, which aims to unify and increase access to microscopy in Chile and neighbouring countries.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I think my decision to become a scientist was highly influenced by my parents. I was born in the countryside of Chile so I always had access to nature. My mother always had plants at home and she knows a lot about medicinal plants for instance, she studied this, and she taught me about this. My father used to take me with him to do bird-watching. I remember him showing me how to use binoculars to watch animals, and a magnifying glass to observe insects. They both motivated me to learn how to solve problems, which I think is the foundation of the work of any scientist. I think problem-solving skills are not just essential for science, but also for life. I went on to specialize in Science during high-school, then studied a BSc in Biology, later a PhD, and then a postgraduate degree in Scientific photography, which I studied in Madrid. This course was amazing! I learned about all types of scientific photography – microscopy, macro-photography, essentially they teach you how to photograph anything: slow motion, fast motion, big scale, small scale, we get to work with the police and the army. I got to work with a teacher who was extraordinary.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

I always loved microscopy, since I was a child. When I joined the career of science, the disciplines of molecular biology and genetics/genomics were at the peak. This was a bit demotivating to me because I wasn’t so interested in genetics. I wanted to be able to see these processes through microscopy, using different techniques that I was able to learn and develop. I had access to one of the first confocal microscopes in the region where I was working. What happened when this fancy microscope arrived is what tends to happen in many places with limited resources: there were no specialists or anyone with the skillset to handle the microscope. The microscope was sophisticated, but no one was able to make the most out of it. I then started learning about this microscope and about microscopy by myself and used it as much as possible. Eventually one of the PIs (Dr. Sergio Marchel) asked me how it was that I knew so much about the microscope. I told him I needed to use that microscope for specific questions I had. He was surprised and told me that since I had learned so much on my own, he would support me in sending me to courses to learn about microscopy. He hired me and I worked with him for 10 years. He was super encouraging and supportive when it came to allowing me to learn and attend relevant courses and workshops at home and abroad. The unfortunate thing in the field of Microscopy is that there is no such thing as a career or degree in Microscopy. It’s mostly scientists who choose to become microscopists within the scope of their own careers. Since I was working on microorganisms, microscopy went hand-in-hand with my own research. My PhD thesis was mostly about microscopy – it became a beautiful piece with a lot of imaging and photography. During this time I got to work a lot with both optical and electron microscopy. In this field one never stops learning – there’s new techniques, new applications, new microscopes being created/released all the time. We submitted an equipment grant and we got funding for a lattice light sheet microscope – the Zeiss 7, and now many people are keen to use it. I am passionate about this type of microscope and is something I’m fully dedicated to. In South America there are very few specialists, and it’s a similar situation as what I mentioned regarding the confocal microscope: if there are no specialists, the microscope is underused. So I’m studying again everything there is to know about lattice light sheet: the techniques for sample preparation, suitable fluorophores and dyes, all the possible applications, image analysis, etc. I’ve been doing this for a few months and have advanced enough to be able to provide support to the users coming from different areas of science. I now work together with the director of the Imaging Center, and Pamela Mena, another colleague working on the Flamingo – a low-cost lattice light sheet microscope which can be built from Legos and can use different setups and configurations.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Chile, from your education years?

I think my undergraduate degree was probably the best one can hope for as a scientist. The range of topics they taught us was extraordinary. We started with full organisms, then cells, then proteins, then genes. We went from macro to micro. They also instilled the scientific method very rigorously. All the time they taught us how to formulate scientific questions and how to think as scientists in all sorts of situations: from climbing a flight of stairs, to actual scientific questions. We dedicated enough time to philosophize. This was truly valuable, because I feel in terms of knowledge, one can find most things in books or on the Internet – there’s no need to sit in a classroom to read a paper, and as scientists we need to read all the time. However, we were not just taught how to find information, but most importantly, how to think, and how to develop the scientific mind. Perhaps for many people, problem-solving skills come instinctively, but the structured scientific thinking is something one learns, and I think it was extraordinary that they taught us how to do this, early on in our career.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a Bioimaging Unit Director at Universidad Mayor, heavily involved in microscopy?

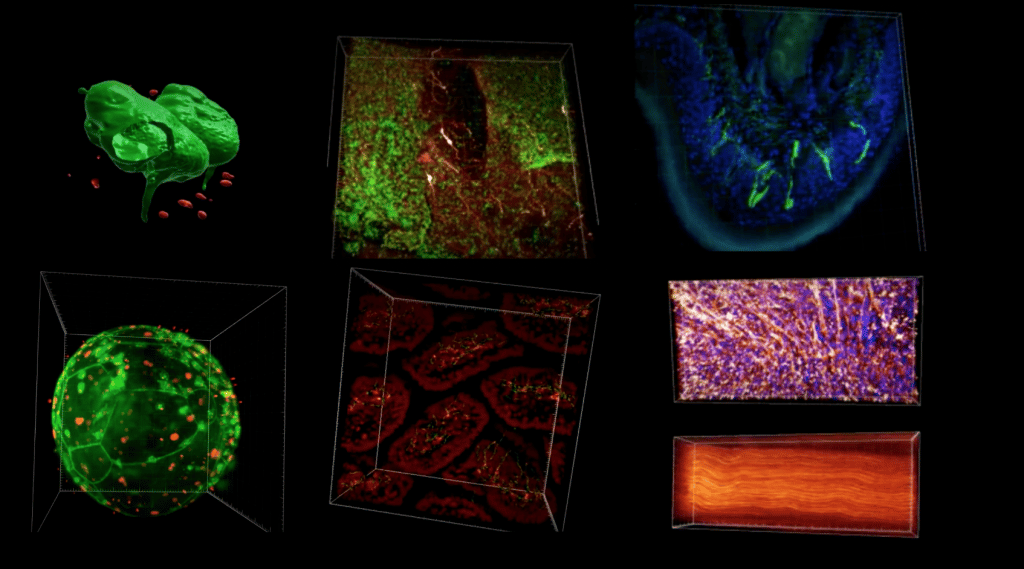

I’m the coordinator of the Bioimaging Unit. It comes with new challenges, which I find inspiring and motivating. Scientists come to you and ask for your help to image a huge range of things: anything from a full mouse brain, to a sub-cellular structure. My job is not just image acquisition. I feel the microscopist’s job is divided into 3 stages: sample preparation, the actual microscopy (including the choice of which microscope to use), and image analysis. Those 3 things are relatively new for lattice light sheet. For instance before the microscope arrived, I was optimizing sample clearance for various types of samples. Once the microscope arrived, we optimized image acquisition, and at the moment I am working on the 3rd part, which is image analysis. With lattice light sheet microscope one can easily acquire 1TB of data, and so the challenge comes during image analysis – how to handle all this data without things getting out of control. I’ve been exploring all the tools to really make the most out of the whole technique. Coming back to my point on the technique of sample clearance, there are nowadays tons of methods to make samples transparent and so we have optimized several methods for different types of sample. On this line, at the moment I am also working on the establishment of expansion microscopy – this is a technique that solved the issue of super-resolution in an indirect way. Instead of relying on optics to achieve super-resolution, we expand the sample. This is a brilliant idea! So at present I will start working with some scientists who already have more experience using this technique, and will take it from there to be able to cater for all the needs of the scientific community at my institute.

How did you become involved with LiSIUM? Can you tell us more about this initiative and your expectations?

The director of LiSIUM and the director of the Centre for Integrative Biology designed this project. I am involved because the initiative involves the Imaging Centre. The idea is to have a hub of expertise in light sheet microscopy not only for Chile but also for Latin America. For this we hope to establish the Flamingo microscope to be able to bring that to the entire continent. This overcomes the complexity posed by the Zeiss microscope, for which anyone interested would have to come to Chile to learn how to use it – it poses a problem of accessibility. I also help Pamela Mena, who is learning how to build the microscope, with my expertise in the Zeiss. We’re working on establishing the sample preparation techniques.

You are also a founding member of SEECA (Sociedad de Especialistas en Equipamiento Cientifico Avanzado). Could you tell us more about this Society, its aims and activities, and your role?

SEECA is a group of scientists who realized that we didn’t have a Society of Microscopists in Chile. We wanted to facilitate training and resources. Several microscopists from across Chile came together to discuss the microscopy needs of the scientific community, and how best we could address those needs. We started as a small group and eventually it grew into an actual organization. I believe now we have united all Chilean microscopists. It was challenging because each University/research centre has its own microscopes, but the information on which microscopes were available and where, was not publicly available. What we did was to generate a database with all the regions of Chile, and contacted each centre not only to gather information on the infrastructure, but also other resources available in each place: like courses, workshops, conferences, scholarships, and expertise in general. We hope this will also help us in the formation of microscopists. As you know, currently there is no ‘Microscopy’ degree, or an official career. I for once, don’t have a certificate or a diploma or anything that says that I’m a microscopist. It’s assumed from publications, but even so, some people are not included as authors, so the problem arises in how to show this expertise? We want to facilitate this. Regarding publications, in my particular case, it’s up to us and the groups we collaborate wirh, whether we appear as authors. If we do, we often have to dedicate extra time to this. My main job is to provide service, not to specifically work on publications. I’ll give you an example: I have a collaboration with groups in Valparaiso, where first I did consultation on how to prepare samples, and then I did all the image analysis. This is something I can do from home, so I am able to collaborate. With another group, I developed a protocol during my working hours – it involved all the image acquisition and image analysis, and so I was an author too. I like it this way. I wouldn’t like an imposition from a University or centre prohibiting authorships.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Chile?

I’ve been able to work with Argentinian groups mostly. I was there for 6 months in Rosario, working on microscopy. I had a very good teacher there – Jose Pellegrini – who taught me a lot. He was director of the microscopy centre in South America – he taught me for instance, how to solve problems with few resources. I think resourcefulness is a vital tool for science and microscopy, especially in Latin America. It’s a pity to not do an experiment because of the lack of a component, especially when you can design it yourself.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Chilean researcher, working abroad?

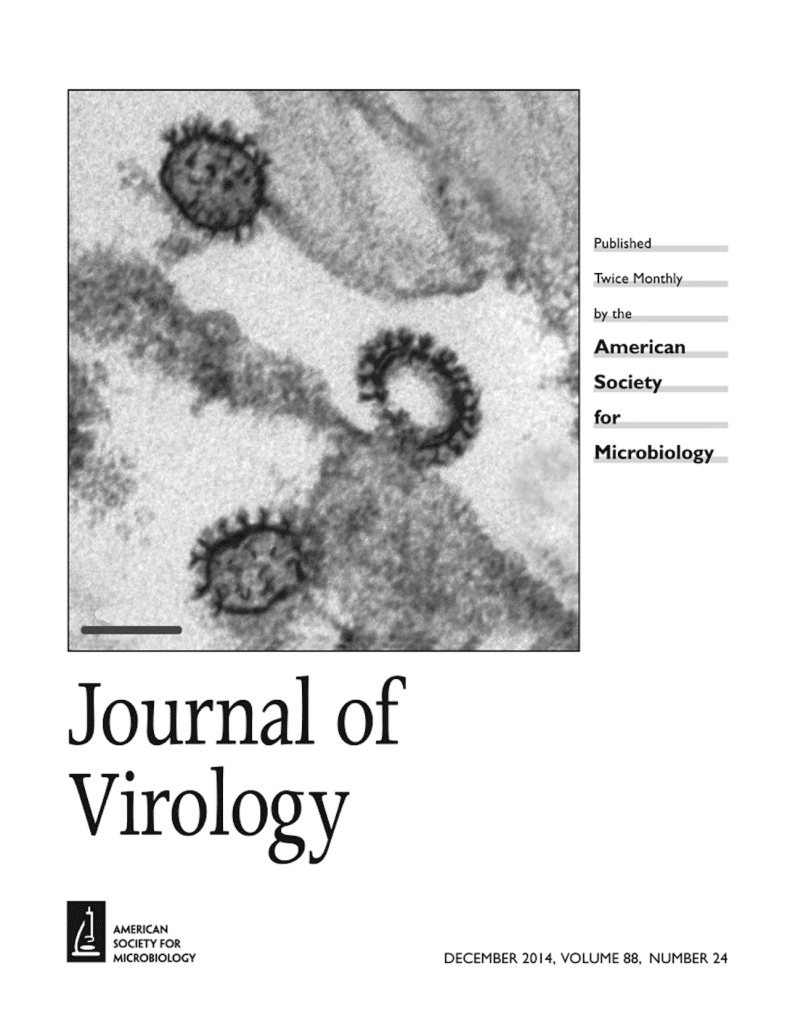

Mostly scientific. When I worked in Spain, I was working on a virus which I needed to image. I wasn’t able to image it! I used cryo-EM, conventional EM, and a million other techniques. Then it was difficult to bring the virus to Spain. Eventually we managed to get an image. Eventually when we published it, an image of this virus was chosen as the cover of the Journal of Virology. This was a challenge because I had worked with this virus for a long time, and had never been able to take an image before I went to Spain. It’s different to see a schematic than to see the actual image of something you work with. It’s like black holes: some people have done calculations of black holes and knew the theory about it, but eventually I am sure being able to photograph it was a unique experience. I think this is a microscopist’s reward: to be able to see something like a virus or something we otherwise only imagine in concept.

Who are your scientific role models (both Chilean and foreign)?

My mentor, Dr. Sergio Marchel, who works at Universidad Católica de Valparaiso, is one of them. He motivated me to become a scientist. He is the type of person that sees potential in someone and helps you reach and exceed this potential. He facilitated learning, he would encourage me, etc. He was able to identify people who haven’t lost the capacity of wonder – his philosophy is that a scientist should never lose this capacity. He is now a true role model. He used to love the science he was doing, and would philosophize about the science and the reasoning behind. To me he was like scientists in the movies! Among foreigners, Dr. Luis Monje who was the leader of the postgraduate degree in scientific photography in Spain. He was incredible. He loved what he did, and he wasn’t interested just in the publication numbers and impact factors. Another thing is that he is hearing-impaired, and he managed to break all barriers. He told me even that this is what allowed him to get into a bubble where he could think a lot without interruptions. That he learned how to use other senses to do science, and this allowed him to go into the area of photography. He had all sorts of photographs of everything and anything. He was able to modify photographic cameras to do the type of photography he needed/wanted to do. He taught me to lose the fear to disassemble something or modify something.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Chile, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I’ve always worked with more women than men actually. I always had more colleagues who were women. And because you spend so much time in the lab, you end up seeing your lab-mates as your family. At least this was the case in my career. For instance most of the members of SEECA are women. First it was only me and Jorge Toledo. When we were searching for microscopists to join the group we realized the majority were women. And they’re extraordinary scientists. I think the most complicated time for women in particular, is when scientists decide to have a family. My colleagues leave for maternity leave and when they come back to this career which is very competitive, they are left behind. This is something that should really change. It should be controlled in some way – it shouldn’t be fair in any competition anyway, that some people have to stop and everyone else goes on, and this affects the person who had to stop. It’s the wrong way of seeing it and of handling it. I had colleagues who would come to work up to the last possible minute before the delivery date because of this pressure, and I think sometimes they shouldn’t have been there anymore. It’s a complex issue to solve, really.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

Light sheet of course! I’m super excited about this microscope and everything one can do with it. I find it’s such a simple concept: to generate a sheet of light and be able to visualize things. Usually, when you are at a confocal microscope, you get a lot of information from a very small sample section. This is not as global as what you can obtain from light sheet. With light sheet you can image an entire brain. Now the challenge is data analysis, but not the microscopy part anymore. I’m amazed by the capacity of this microscope. It’s revolutionary. And hand in hand with other technologies, like expansion microscopy, what we can achieve is really incredible. Every time we are pushing the limits of what we can achieve with light 🙂

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

One of the most extraordinary things I’ve seen was the virus I worked on during my PhD – an orthomyxovirus. By light microscopy I could see filamentous structures of 300-500 µm which were recognized by antibodies. I started studying this until I was able to image it in Spain. There I realized these structures were giant filamentous viral forms. This was the biggest thing for me. I didn’t think viruses could ever have those shapes. My PhD thesis focused on isolating these viral particles and to define what exactly was their role. I realized this was a general characteristic of the orthomyxovirus. I later was able to see this in influenza viruses using cryo-EM. It was fantastic to have been able to see this.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Chilean scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

My main advice would be to be sure to stay up to date. And also to make sure you get recognition for your expertise in microscopy – make your expertise visible and tangible for others. Unless you make a name for yourself as a microscopist, it’s really difficult to get fair conditions and even fair treatment: for instance, while you might get a job, you might not be well paid. This would be my main advice for someone wanting to do microscopy.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Chile a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

Nature! Chile has Torres del Paine, which is truly amazing. If you’re a photographer or a nature lover you have to go there: this is beautiful and it has for instance, colours I had never ever seen. The water, nature, everything is huge and novel. You feel small there. It’s a humbling experience to be here. It’s an unforgettable experience to be there.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)