An interview with Leandro Lemgruber

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 15 March 2022

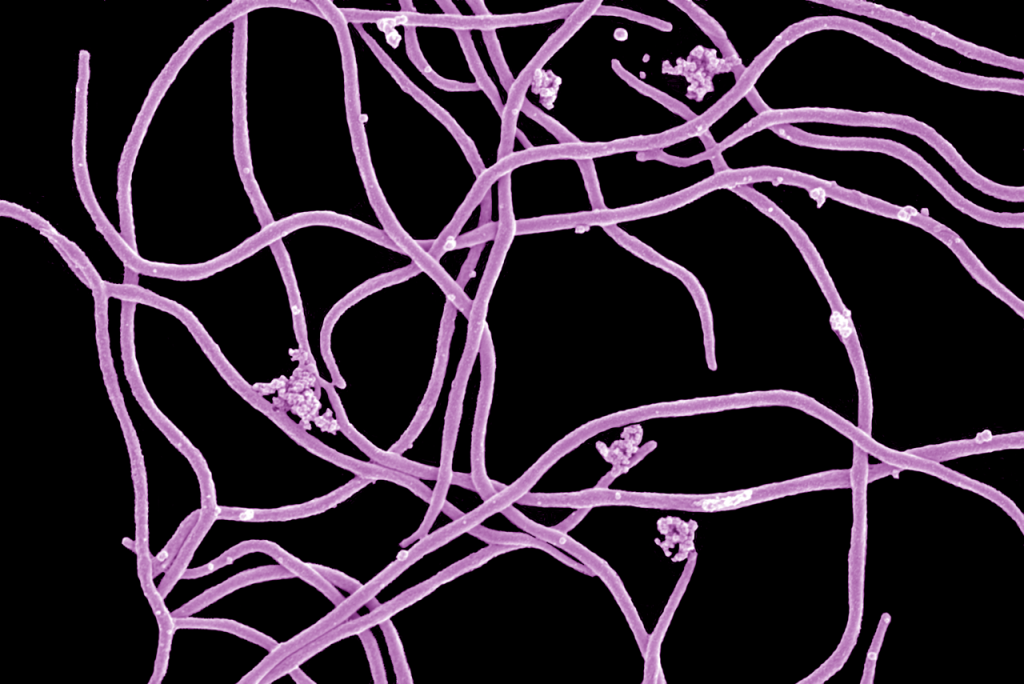

MiniBio: Leandro Lemgruber is the facility manager of the Glasgow University Imaging facility in Scotland, UK, and has been in this role since 2015. He has worked in several capacities as a microscopist in Brazil, Italy, Germany, the USA and the UK. Leandro began his work in microscopy and parasitology since his undergraduate degree. He did his early studies, up to his PhD at the Hertha Meyer Cellular Ultrastructure Laboratory, at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, mostly in the lab of Dr. Rossiane Vommaro and Prof. Wanderley de Souza, focusing on the Apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. He then did his postdoc between 2010 and 2012 in Heidelberg University in the lab of Prof. Freddy Frischknecht, funded by an Excellence Cluster CellNetworks fellowship, where he focused his imaging-based work on Plasmodium and Borrelia. After this, Leandro became a research support specialist at the Electron Microscopy Resource Centre at Rockefeller University, and then a research associate at the National Institute of Technology in Brazil, before joining his current position at Glasgow University. During his career, Leandro has received several awards and recognitions for his work, including the prestigious Wellcome Imaging Award. He also is the scientific editor of inFocus, and a committee member of the EM section of the Royal Microscopy Society.

Brazil has a long-standing history of contributions to science both, in Latin America and world-wide. It is the land of scientists as renowned as Carlos Chagas and Oswaldo Cruz. It is also a country of fascinating biodiversity, attractive the whole world around. Before becoming a scientist, were you aware of this heritage? What inspired you to become a scientist?

To be honest, my first wish was to study history, rather than science. What pushed me to switch to Biology was some form of inspiration from the film ‘Outbreak’ (1995, by Wolfgang Petersen, based on the nonfiction book ‘The Hot Zone’). I was fascinated by the scene where they are able to see the virus by electron microscopy. In the mid 1990s I was also reading a lot about, and very interested in, infectious diseases, where indeed I read about the work of Carlos Chagas and Oswaldo Cruz. I was deeply interested on how Oswaldo Cruz aimed to eliminate Yellow Fever from Rio de Janeiro, and the unrest that took place among the population when the government wanted to enforce vaccination in the region.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy and infectious diseases. What inspired you to choose this career path?

In fact I began my career going more towards imaging rather than infectious diseases. I started my career working on neuroscience. And here I found my love for imaging. I would do cryo-sections and immune-staining to see different neurons and other brain components. Here I learned how to do sample preparation and tissue preservation, how to prepare a good protocol. This was all with optical microscopy.

What also inspired me to go into microscopy was that early on in my career as an undergraduate, there was a subject of ‘Cell Biology’. This was taught by the professors, including Dr. Rossiane Vommaro with whom I eventually did my MSc and PhD. They used a lot of microscopy (both optical and electron), and they made emphasis on how microscopy plays a key role in cell biology research. This was fascinating to me. Based on this, I did a second internship focusing on Trypanosoma cruzi, but at the time not on microscopy, rather immunology. I soon realized I didn’t really like immunology. But from the point of view of infectious diseases this was fascinating. From this experience I then did another internship, where I was able to combine microscopy and infectious diseases. This lab was fantastic because it was the first lab in which had an electron microscope, and one of the first confocal microscopes in Brazil. The focus of this lab was on ultrastructure and cell biology of pathogens (Giardia, T. cruzi, Leishmania spp., Amoeba, Toxoplasma, Plasmodium) using a plethora of microscopy methods.

Brazil has renowned and historical institutions dedicated to research (and microscopy). Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Brazil, from your education years?

Something rather strong in Brazilian education is that early on in your career (already from BSc level), there is something called ‘Iniciação científica’, where you are able to do long internships in labs. Early on, you get the opportunity to get hands on, on the wet lab, and have your own project. The best part is there is a system of funding, where the government finances these internships. This incentivizes people to follow this path. Currently perhaps, these funding options haven’t been updated since a decade, but around ten years back this initiative was crucial. The idea in general was extraordinary.

Another important thing is that in my experience abroad, I’ve seen that undergraduate internships are limited to a few months – they are relatively short. In Brazil you could do an internship for as long as you wanted (the entire bachelors degree), meaning you really could develop your own project and learn a lot while doing your own experiments. So, once you come out of the undergraduate, you are very experienced. I’ve never seen this system anywhere else in the world.

In the lab we didn’t have technicians. You needed to learn how to do everything yourself. Of course there was huge expertise around you, whereby the other PhD students, postdocs, and PIs would come with you to the bench and teach a lot. But you always had the opportunity to be independent. It was a center of microscopy, and so we had multiple microscopes available: confocal, TEM, SEM, widefield, etc. You learned how to use these big machines on your own already as a student – you lost this fear of big machines relatively quickly. Moreover, there were no time limits on how long you could use these microscopes. You could use them as much as you wanted and keep learning.

Throughout your career you have belonged to various world-renowned centres of microscopy? Can you tell us a bit about your path, and how did this shape you as a microscopist both at home and abroad?

Where I began my career, it was fantastic for me to be among great microscopists. This gave me an excellent opportunity to learn about microscopy both theoretical and practical. This made it possible for me to get funding to go abroad. I spent some part of my PhD in Italy, to learn cryo-EM techniques. Because my partner was in Germany, I focused my search for future career steps to German labs. This opportunity arose when I went to a symposium in the USA: Microscopy and Microanalysis in 2008. Freddy Frischknecht, from Heidelberg, was there, giving a talk, and I met him there. We spoke, and this was the spark for the idea to work together. This brings me back to a great quality of Brazilian education: you have the opportunity to go to congresses from early on in your career, which allows you to present your work and build a network from early on, with both researchers at home and abroad.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Brazil?

Not a lot. We had opportunities to collaborate with researchers in the USA – some of these researchers were Latin American. I’d like to think that this was because at the time Internet was a relatively new thing, and so making interactions was more difficult. There was no PubMed, and this limited a lot the interactions. But this has changed now of course.

Having worked abroad, what were some of the things you found to be very different between doing research in Brazil, and abroad?

One of the most striking things is the efficiency and resources with which one can do research abroad. For instance in Germany or the USA (where I’ve worked), if a piece of equipment breaks or needs replacement, you won’t spend months on end waiting for it. It will happen relatively quickly, while in Brazil this is not the case many times.

Another thing that was strikingly different for me is that the interactions with companies (eg. Zeiss, Nikon, etc) is much higher and efficient abroad. You get to know about new pieces of equipment and new techniques very quickly. This helps in terms of networking as well.

Moreover, during my postdoc I was in Heidelberg, and close to Heidelberg University is EMBL. EMBL is a major hub for research. This gave me fascinating opportunities, including attendance to conferences and workshops which would otherwise would have been difficult to attend.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Brazilian researcher, working abroad?

I have seen prejudice sometimes. I have noticed that sometimes the institution or the country you come from matters in terms of the credibility you receive as a scientist. I’ve noticed there’s a tendency to believe more and cite more, work that comes from other European countries or the USA, as opposed to countries in Latin America for instance.

I think now there is less prejudice than when I began. When I began as a scientist, the Internet wasn’t so available, so it was difficult to know what people world-wide were doing in terms of research.

While I faced prejudice, this was not the case in the group which I joined in Heidelberg. Here I felt very welcome. I think having belonged to this group in Heidelberg also gave me more credibility. People saw me with different eyes. I feel you are perceived differently when you are a Brazilian scientist working in Brazil, as opposed to a Brazilian scientist working abroad. Again in terms of credibility, which is a pity.

But there are efforts from the Brazilian government and perhaps scientific networks abroad that are incentivizing scientific exchanges. I think this will play a key role in changing the playing field on how Brazilian science is perceived.

Who are your scientific role models (both Brazilian and foreign)?

During my PhD I had several role models: Celso Sant’Anna, now a leader in the National Institute of Technology in Brazil, and Kildare Rocha de Miranda, who is now the leader the CENABIO (Centro Nacional de Bioimagem). They are both very competent, know a lot about microscopy, and are excellent teachers. I also had excellent female role models: Rossiane Vommaro and Narcisa Cunha e Silva. Rossiane was my PhD supervisor. Narcisa is one of the best professors of microscopy and cell biology. The fact that both of them would see people’s potential rather than just using students as ‘cheap-labour’ was key for me. They were developing potential. They never acted like they were wasting their time training a young student. Freddy Frischknecht was later an important person in my career during my postdoc and later he helped me particularly when I decided to become a head of facility.

From my personal experience, I have only worked in 2 countries world-wide where the gender gap in science is not so pronounced: Brazil and Portugal. Was this something that influenced you? How?

An important thing to say about Brazilian research: faculty positions are public- not private. Because you are a public servant, the salary is the same for everyone, regardless of socio-economic background, racial background, or gender. There is no salary negotiation: everyone is the same, and this avoids toxic masculinity. There are still more men than women occupying certain positions of leadership, and more white scientists than black scientists. But I feel in Brazil this is less pronounced, though, than what I have seen abroad.

You are, and have been for a while a well-known imaging facility manager. How did this come to be? What led you to this decision?

The concept of imaging facilities was novel for me when I worked in Europe. I saw this first during my time as a postdoc. For me this concept was unique: equipment being maintained and organized as a hub. Here I realized I liked more to be at the microscope than at the bench. I went to the European Microscopy Congress, organized by the Royal Microscopy Society, this opened a new world for me: the idea of facility, and eventually becoming a facility manager. And is what I am now passionate about.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

I love SEM. You can stay hours and hours creating images. I also love fluorescence microscopy – I like bright things and colours, but SEM is my favourite by far.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

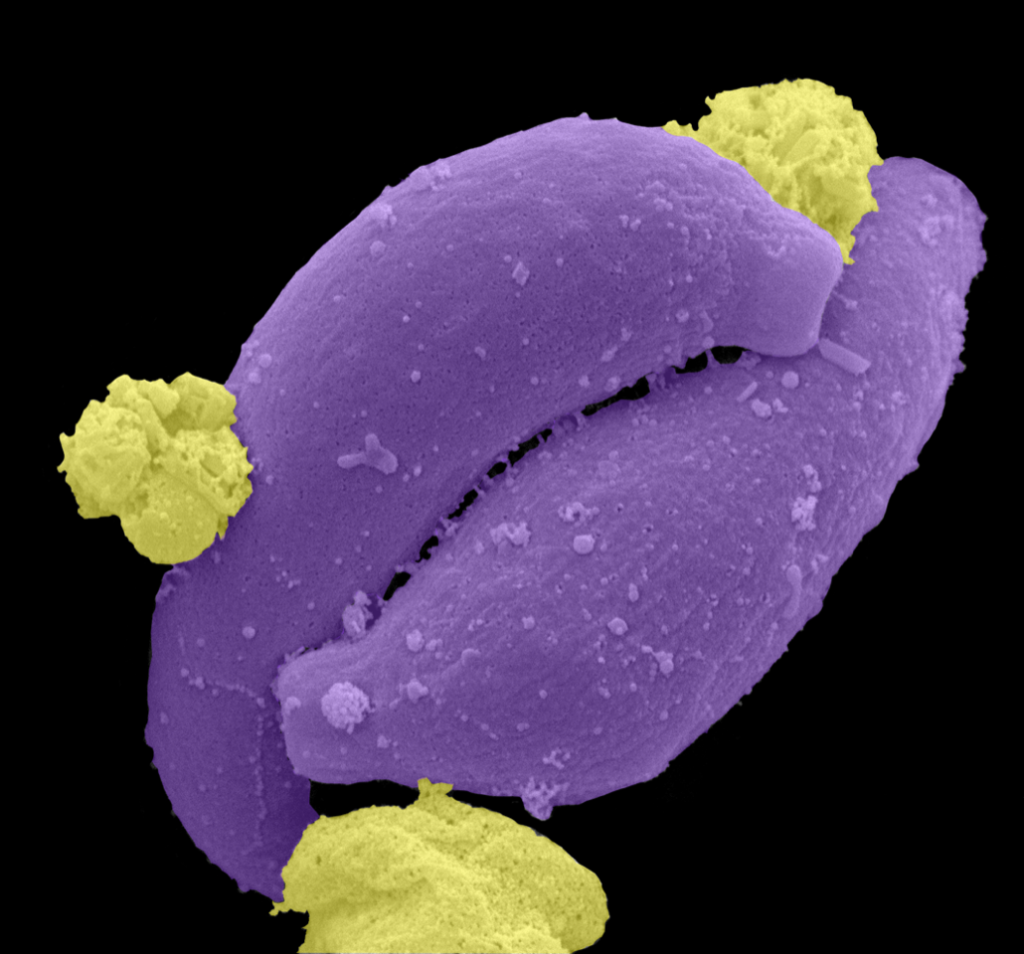

Very hard question….. there were several moments that I was gobsmacked when using a microscope. One of the first of these moments was when I used a FIB-SEM when milled through the cyst of Toxoplasma gondii – it was fascinating cutting and imaging such structure. The other moment was when I observed actin filaments in membranous protrusions of Theileria using Cryo-EM – it was one of the first observations of in situ actin filaments in Apicomplexa parasites.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Brazilian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

I think there are advantages coming from disadvantages in Brazil. The fact that there is little money for research compared to other countries, and the fact that we have to import many consumables, this means we have to do what we can, with the resources we have. So this triggers a significant amount of creativity and resilience in Brazilian researchers. Moreover, the fact that you can have your own research project and drive your own project since very early on in your undergraduate education is something unique. My advice to young Brazilian researchers is that you should really take advantage of both of these points.

Where do you see the future of microscopy heading over the next decade in Brazil, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

In previous years, the Brazilian government invested a lot in science. Many new pieces of equipment were bought and updated, and there were huge leaps in terms of infrastructure. This allowed for instance the acquisition of the first cryo-EM microscope. This also played a huge role in attracting back Brazilian scientists working abroad. And the government made a huge effort in bringing back this talent. At a point this changed hugely: there were huge cuts to science. This resulted in many Brazilian scientists again moving out of Brazil to work abroad. Still, Brazilian scientists in Brazil are doing extraordinary efforts promoting scientific collaborations both at home and abroad, and linking expertise within the region. Also, Brazilian scientists abroad made networks abroad. With Zoom and other tools, it is easy to continue those interactions. Moreover, technological innovations, such as robotics, allow you to operate microscopes remotely. This facilitates science and connections with other researchers, and I think this will impact how we do research world-wide.

Finally, Brazil is the largest Latin American country, and one of the largest in the world. Beyond the science, what do you think makes Brazil a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

If you’re a student, you’ll be in a lab with many diverse backgrounds. This makes you grow as a person and as a scientist. Furthermore, Brazil is a wonderful country, with wonderful weather and wonderful beaches!

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)