An interview with Aline Araujo

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 19 April 2022

MiniBio: Aline Araujo Alves is a postdoctoral fellow at Institut Pasteur in the lab of Philippe Bastin since 2020. She has previously worked as a visiting scientist at University of Oxford and Oxford Brookes University. Her research has mostly focused on Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma brucei cell biology. Aline did her BSc in biology at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, and later her MSc and PhD in cell biology and parasitology, at the Hertha Meyer Cellular Ultrastructure Laboratory, at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in the lab of Dr Narcisa Cunha e Silva. During her career, Aline has helped develop multiple methods and tools that have benefited the research of the labs she has belonged to.

Brazil has a long-standing history of contributions to science both, in Latin America and world-wide. It is the land of scientists as renowned as Carlos Chagas and Oswaldo Cruz. It is also a country of fascinating biodiversity, attractive the whole world around. Before becoming a scientist, were you aware of this heritage? What inspired you to become a scientist?

My relationship with science began in the classroom. I decided to become a scientist in my 6th year of school when I was 10-11 years old. I really liked my biology classes. I studied in the public education system of Brazil, and one finds within this system, teachers who are devoted to education and who teach out of love. I was really taught by fantastic teachers who incentivized us to develop critical thinking from a young age. My inspiration really came from this time as a young student rather than from historical scientists.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy and infectious diseases. What inspired you to choose this career path?

I was never really attracted to parasites or parasitology. But microscopy was really attractive to me since I was very very young. My father gave me a microscope for children, and I used to look at everything. It allowed me to observe a world we cannot see with our own eyes.

Brazil has renowned and historical institutions dedicated to research (and microscopy). Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Brazil, from your education years?

During my education, I never studied abroad, but my experience in Brazil was that education there is very inclusive. It allows people to follow whichever road they wish. I had a chance to study many things and specialized only relatively late rather than discarding subjects early on. I remember I joined University wanting to do genetics, and a professor took me to a lab of genetics. That was one of the first labs I visited. I quickly realized that I didn’t really want to work with Drosophila and thought this wasn’t really for me. I couldn’t imagine myself in this field. And so, I moved on to a biochemistry lab, where I found my real passion. Within my BSc degree, I had the option of choosing anything I wanted. So Brazilian education, in my opinion, leaves all options open to students, and I find this very valuable.

Throughout your career you have belonged to various world-renowned centres of microscopy? Can you tell us a bit about your path, and how did this shape you as a microscopist?

Throughout my career, I have worked with many types of microscope. I started with basic optical microscopy, but very early on, I started using atomic force microscopy. This was the first time I was in touch with advanced types of microscopy. I worked again with microscopes in the lab where I did my MSc and PhD. I actually joined the lab of Prof. Wanderley de Souza because I wanted to learn about microscopy. The lab was really fascinating. There were multiple rooms with multiple microscopes, and there were over 50 people working in the same lab (within different sub-groups). There was a huge heterogeneity in the expertise and the people, and this was very attractive to me. Being in a lab with such vast microscopy expertise was vital for my career. There was a huge exchange of knowledge, and I had many colleagues and professors who were role models for me. It was from my colleagues that I learned most.

Altogether, though, I come from a background with limited resources, so from very early on, many of my career decisions have been guided by the need to get remuneration, so as to be able to pay for my studies and living expenses. The fact that the government provided fellowships for Iniciação Científica gave me the opportunity to work in research, and study at the same time. It’s not a huge amount of money, but it gave me the possibility to afford this career. My first supervisor, Dr Deborah Foguel, was very supportive and together we applied for a fellowship that allowed me to work with her for some time during my undergraduate studies. After two years, I moved to a different institute, where I was offered a better stipend, and there I worked on the development of drugs. Then I went to work at a private institute, but I found it a difficult transition: I felt I lost scientific independence, which was important to me. So, I went back to academia and joined the Hertha Meyer Cellular Ultrastructure Laboratory at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Prof. Narcisa Cunha e Silva, who became my MSc and PhD supervisor, had a fellowship that was immediately available to me, and in her lab and in this institute I had a fantastic opportunity to work on cell biology and imaging. I think altogether, my career wasn’t only motivated by my research interests, but also by the financial possibilities at the time. Only later in my career, I had the chance to go for some time to University of Oxford to work with Dr Jack Sunter. Afterwards, I joined Institut Pasteur as a postdoc in Prof. Philippe Bastin’s lab.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Brazil?

In the lab of Prof. Wanderley de Sousa, I had the opportunity to collaborate with many people, as it is a famous centre of microscopy, renowned worldwide. During my studies, I was able to attend a course on Molecular Biology of Parasites in Argentina. There I met many students from many Latin American countries. I also met many researchers whom I previously only knew by name from publications. I realized we have a similar reality across countries in this region of the world: very hard-working, bright scientists with little resources.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Brazilian researcher, working abroad?

I think the most striking thing after I went abroad was rather that I joined labs with plenty of resources for research, so for me, it was altogether an extraordinary experience, where there were no limits.

However, the challenges I have noticed is the limitations we have in terms of our scientific reach in Brazil, and the perception this can lead to. What I mean is the following: in academic science, there is a lot of focus on numbers: number of publications, impact factors, how many projects you do, how many collaborators you have. This all ‘classifies’ or ‘grades’ you as a scientist. In Brazil, a lot of fellowships and grants do not include publication costs, and these costs are many times prohibitive. Some scientists end up paying these costs from their own pockets. In my own case, we had to choose journals where there were no submission costs. What is shocking to me is that I came from a lab in Brazil with a lot of resources, so if this was my reality, I can’t imagine the reality of labs with even fewer funds. When I came to Europe, I realized that the choice of journals on which to publish was hardly ever dictated by resources. This really is a limitation to Brazilian science, and how our science is perceived abroad (because of the journals in which we can afford to publish, rather than the quality of science itself). Some Brazilian journals were created due to the enormous gap in affordability- they allowed us to publish our work. I think biorXiv and other preprint servers in more recent years have been equally enormously beneficial for Brazilian scientists, and I imagine other scientists from developing countries.

Who are your scientific role models (both Brazilian and foreign)?

The main role model for me was my first supervisor, Prof. Debora Foguel, from the Institute of Medical Biochemistry, from the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. She was the person who most inspired me during my entire career. She is a fantastic scientist and a very warm person. I was 17 years old when I joined her lab, and she never told me I couldn’t do something because I was too young or too inexperienced. She gave me a lot of autonomy, a lot of intellectual freedom. Moreover, she taught me I could explore whatever I wanted rather than focus on any one single topic. So this made me a versatile and resourceful scientist- which I consider myself, even to this day.

Among the non-Brazilian scientists, Dr Jack Sunter is another important role model in my career. He was essential for my PhD, guiding me through my first experience abroad. He is a brilliant scientist, with a lot of enthusiasm and good ideas. He is fast and fierce but also kind and joyful. It was a great pleasure to work with him.

Brazil has one of the best equality in terms of gender I have encountered as a researcher, with women heavily involved in research, at various leadership levels. Was this something that influenced you? How?

In Brazil, I only ever worked with women leaders during my career, both in industry and academia. That shaped my vision that I could become a leader myself and that there was nothing I couldn’t do because of my gender. For me, it’s natural to think a woman can be in a position of leadership. That was never a question for me. And this is even though microscopy is at the interface of physics and biology and highly dominated by men.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

I struggle a lot with choosing one type of microscopy, as all of them have their strengths and can answer different questions. But I feel very passionate about transmission electron microscopy and its diverse applications. The possibility to go from entire cells to even single molecules fascinates me. It opens a whole new world, allowing one to see things from a unique perspective. Doing TEM is super exciting for me, even nowadays.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An ‘eureka’ moment for you?

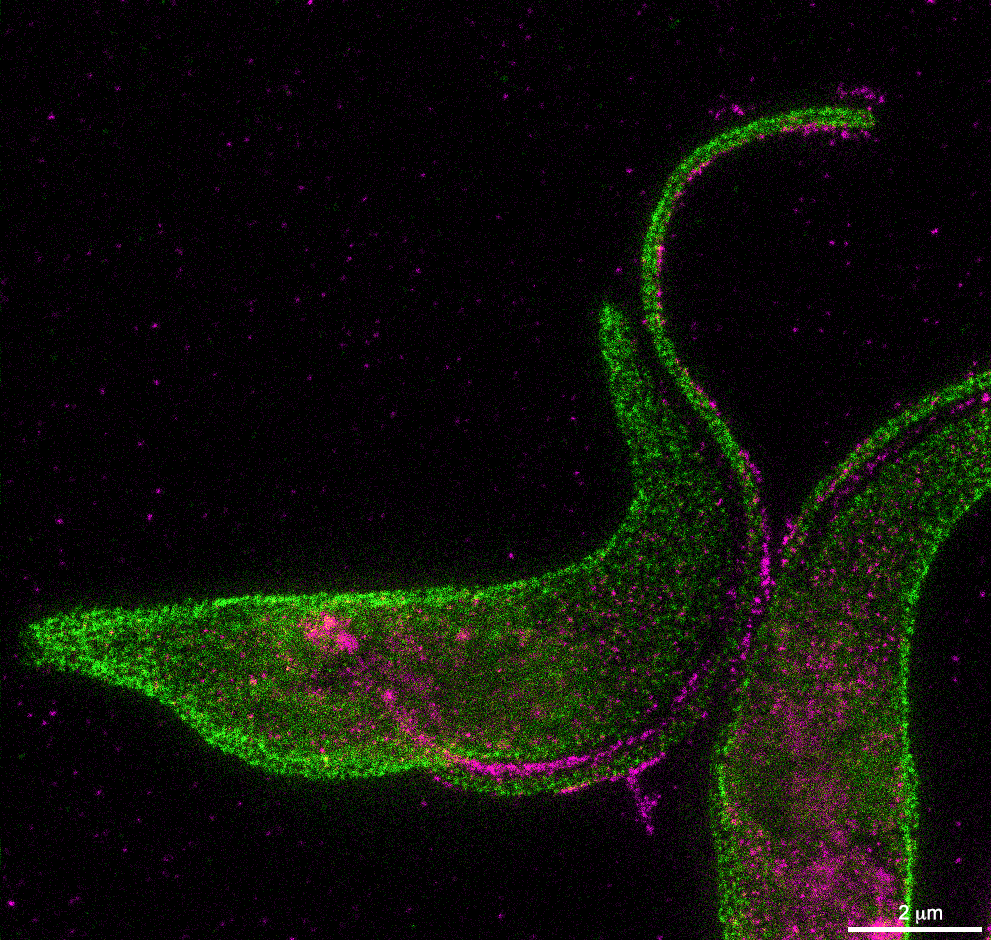

I still remember the day I first saw the localisation of an orphan myosin called MyoF in T. cruzi epimastigotes. At that time, I was working on the T. cruzi endocytic pathway for six years. Our entire group always dreamed about finding a marker for the cytostome-cytopharynx complex, a unique structure involved in the uptake of many extracellular components. Thanks to CRISPR-Cas9, I was able to generate a cell line expressing this myosin fused to a green fluorescent protein. Seeing the MyoF localising only to the cytostome-cytopharynx complex is still one of the most exciting moments for me as a scientist.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Brazilian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

I believe Brazilians are known, worldwide to be able to think out of the box and to adapt. We are also very hard-working. The education system is great, which incentivizes people, from very young, to gain intellectual independence. That is unique, and you should be aware of it.

People now reaching University don’t have the same resources as I did. The sources for fellowships and grants that allowed me to study and work as a researcher were severely cut. Currently, Brazilian science is facing a dark time in terms of financing, and this will likely impact this generation. I think the road right now for young scientists is very, very difficult. My advice would be to prepare for this if you do choose to become a scientist. My other advice is to develop as many abilities as possible. I had a versatile career and was very resourceful: being able to have various types of expertise allowed me to take advantage of various opportunities.

Where do you see the future of microscopy heading over the next decade in Brazil, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

Brazilian scientists are very resilient and perseverant. People are committed to continuing to do science despite the dark times currently ongoing. I think Brazilian science is moving forward because of the efforts of all the scientists there. I just hope these dark times end soon, and new opportunities arise for Brazilian science. I think the fact that there are incentives for collaborations with labs abroad is also an important factor. Brazil is still a reference for many types of research, and this gives us still a place in global science.

Finally, Brazil is the largest Latin American country, and one of the largest in the world. Beyond the science, what do you think makes Brazil a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

Brazil is a great place to work, both as a parasitologist and as a microscopist. Also, Brazil has a very important social aspect: we are very warm, welcoming and empathic and this facilitates integration for foreign scientists. We always try to communicate with everyone, regardless of their language. We don’t like seeing someone isolated so we make the effort to integrate people into our culture.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)