An interview with Moara Lemos

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 3 May 2022

MiniBio: Moara Lemos is currently a permanent researcher at Institut Pasteur in France, where she has helped establish cryo-correlative light and electron microscopy and cellular cryo-tomography for different biological systems. She began her career (BSc and MSc) at the Federal University of Juiz de For a, working on trypanosomes of wild animals. She later did her PhD at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, where she joined her interests in electron microscopy and parasitology. She did her first postdoc working on cell biology and ultrastructure of protozoan parasites at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. She later joined the Brazilian Centre for Research in Physics (CBPF) for a second postdoc, working on intracellular trafficking and biodistribution of nanoparticles in mammalian cells. Later she did a postdoc at Institut Pasteur in the lab of Phillipe Bastin, where she worked on Trypanosoma brucei intraflagellar transport. Moara has extensive expertise in a plethora of electron microscopy methods, and her work has taken her to the Brazilian Amazon among other places, where she has been able to discover novel biology within the local wildlife.

Brazil has a long-standing history of contributions to science both, in Latin America and world-wide. It is the land of scientists as renowned as Carlos Chagas and Oswaldo Cruz. It is also a country of fascinating biodiversity, attractive the whole world around. Before becoming a scientist, were you aware of this heritage? What inspired you to become a scientist?

When I started I had no scientific background in my family. I had no relatives that were scientists. I only knew from what I heard in school, the big names that you mention: Carlos Chagas and Oswaldo Cruz. I remember I was a big fan of Louis Pasteur. I tried to repeat his experiments on biogenesis at home when I was a kid. I think my involvement in science was more related to my natural curiosity about nature. When I was a kid I lived in a house where I had a big garden. I had a mini-forest just for me. I used to mix plants to do some experiments, to try to find a perfume or a medicine. I was trying to play more with that without any guidance. It was something natural for me to do as a kid. I had a friend who had a scientist kid. My family didn’t have much money at the time, and I was crazy about this kit, but we couldn’t afford it. So when I went to her place, I used to play a lot with it.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy and infectious diseases. What inspired you to choose this career path?

I worked a little bit with everything. I had a student grant (as financial aid), but the deal with the University is I had to work somewhere. I worked in biochemistry, botanics, zoology, and then I ended up working with protozoan parasites, which I ended up loving. But actually my first love was microscopy. I was in the first semester of University and was taking some cell biology classes. And one of the teachers showed a SEM image of a macrophage, and I thought ‘This is it. This is what I want to work with’. I tried to work on cell biology first, but the lab placements were very competitive, and I didn’t get in. So I went to work in the meantime with very exotic things. It was then when I went to work on protozoan parasites. And eventually I wanted to mix both. At the University where I did my bachelors, there was no electron microscopy. So I started working with electron microscopy as a MSc student. And there I worked with frog trypanosomes, fish trypanosomes, etc. I was once invited to go to Amazonia for a scientific expedition. There was a region just for scientific research. Five of us were invited to do a screen of the area. I was responsible for taking blood from the animals. I took blood from snakes, frogs, fish, turtles, alligators, mammals. It was super cool. I found lots of different parasites in them. There were some in the amphibians, for which there was no record. I didn’t pursue the project further and didn’t publish, but I think I discovered something new J I couldn’t culture these parasites because we didn’t have the infrastructure, so I could just describe the morphology.

Brazil has renowned and historical institutions dedicated to research (and microscopy). Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your career path and what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Brazil, from your education years?

I went to the institute of Biophysics to do my PhD, and they call this place Disneyland to do microscopy. It was great to be there. I had huge intellectual freedom and infrastructure to do what I wanted. I joined a lab that was part of the lab of Prof. Wanderley de Souza. We had everything. It was extremely cool to be there, and I chose this lab because of the expertise in microscopy. I had also a lot of time to work on all EM techniques. I think I covered the whole toolkit while I was there. In my lab, we had a TEM just for us. My supervisor at the time said, you had to sit at the microscope till death, to really get to know your sample and understand it. I was working at the time on fish trypanosomes. We described a new species that was different from T. cruzi, T. brucei, Leishmania. I had to understand the architecture and organization and morphology, so this time was great. It was really important that we had plenty of time: we didn’t have to compete for microscope time. Nowadays, the microscope ‘park’ of Wanderley’s lab has been transformed into the CENABIO, which has the largest infrastructure for microscopy for life sciences in Latin America. After my PhD I worked as a postdoc in a Brazilian Centre for Physics research, in a EM facility. It was a bit difficult to bridge the communication between biology and physics. I was expected to work on material science, but I realized I missed cell biology, and I really wanted to keep combining both things: microscopy and cell biology. I then met Philippe Bastin from Institut Pasteur and joined his lab. It was perfect for me– I consider I have two sets of expertise: parasitology and microscopy, and in his lab I could join them both. After my time in Philippe’s lab, a new position became available to develop cryo-CLEM. Because I’m a curious person, I wanted to learn cryo-EM, and CLEM and so I applied to this position and eventually got it. I really like it. The lab I joined works more like a hub, so we can work on many projects and research questions at the same time. We set up a new lab from scratch. We bought a high pressure freezer by ourselves, so it has been a nice experience. So I’ve learned a lot and can do a lot.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Brazil?

There was less collaboration between countries in Latin America than here in Europe. I feel here in Europe there is no geographical barrier for collaborations. But in Latin America, although the collaboration was not directly with me, there were collaborations with Institut Pasteur Montevideo. At a time there was a program in Brazil called ‘Science without borders’ and there was a lot of money to promote scientific exchanges, to host people from abroad, and to send Brazilian scientists abroad. Now the science landscape in Brazil has changed a lot: nowadays some people even do postdocs for free just to have experience. The money for science has been reduced by around 70%. So there is not a lot of stimulus.

You mentioned the project you did in the Amazon, which is a natural wonder to the world. Is it easy for scientists within Brazil to explore all these resources you have ‘at home’?

Locally you can, because there are lots of research hot spots in different regions. I was lucky because I had some collaborations which allowed me to go there. But it’s very expensive. For you to have a better idea: we needed amphibian cars to be able to enter the lagoons, and we had helicopters available because the areas were too difficult to reach – so it’s expensive. It’s feasible if you collaborate, for instance with the University of Amazon, or others closely located in this area. Otherwise, cost can be prohibitive.

Who are your scientific role models (both Brazilian and foreign)?

Abroad I have a very special one – Philippe Bastin: I learned a lot from him and I admire him not just because of his scientific knowledge, curiosity, ethics and expertise in microscopy, but also the human side. I like how he sees science and how he makes connections between things. In Brazil I had Wanderley – he was the one that allowed me to invest time, to play on microscopes. Kildare Miranda, now director of the CENABIO, was also a great mentor. The way that he spoke about microscopy and the theory behind, was inspiring.

Brazil has one of the best equality in terms of gender I have encountered as a researcher, with women heavily involved in research, at various leadership levels. Was this something that influenced you? How?

To be honest, when I was there I didn’t realize how unique this was, because this was the norm in Brazil. I only realized that science is a male dominated field when I moved to France. Only then I understood the differences. And this allowed me to understand why female group leaders have to be strong and need to fight for what they want. Before this I had not been exposed to this reality.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

That’s a difficult question! Ok, but at risk of causing jealousy among the other types, I’ll say my favourite is FIB-SEM. You have the full cell in your hands to explore in detail, which is unique.

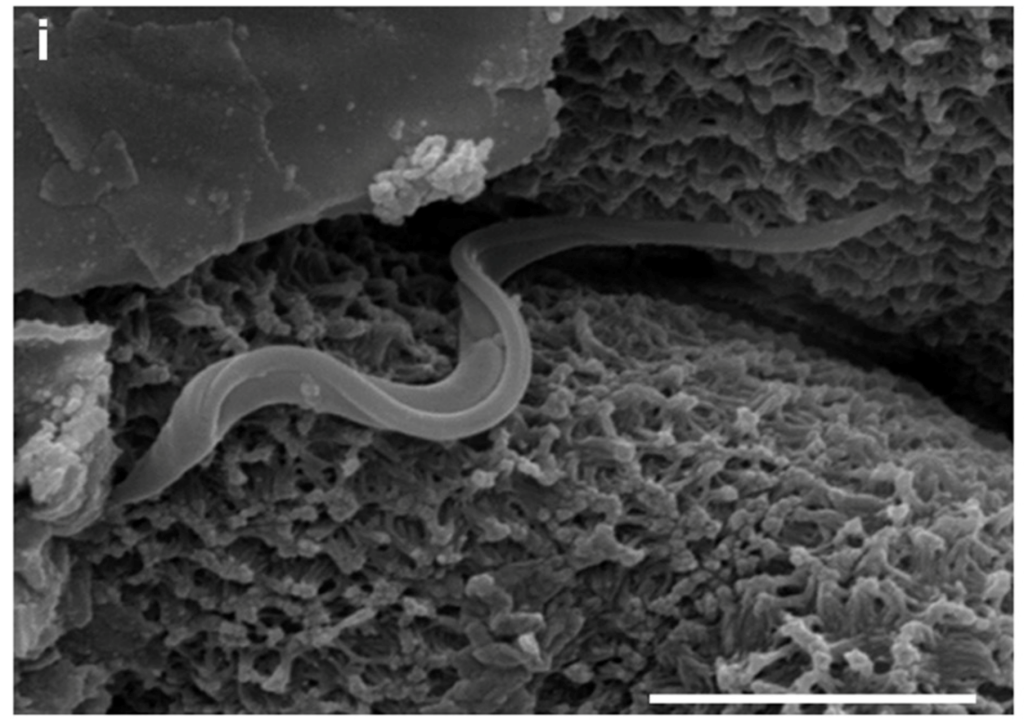

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An ‘eureka’ moment for you?

There are so many things! One thing I really like is that I know that when I come to the microscope, I am the first person seeing a specific phenomena. For example, I did a dissection once on a 2mm leech, and found a trypanosome there. It’s like opening a curtain and finding a secret. It’s a ritual for me J I go to the microscope and I open a curtain to the unknown. About leeches, I found many in the Amazonia, even inside alligators’ mouths. I find this extraordinary biology.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Brazilian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Be loyal to your passion. And don’t give up. It won’t be easy, but you will have a lot of fun. When you reach your different goals either big (like defending your PhD thesis), or smaller ones, like even sitting at the microscope and seeing something nice, it’s a gift. You feel good because of this. And finally, you have to work very hard!

Where do you see the future of microscopy heading over the next decade in Brazil, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think the future will be to understand the ultrastructural anatomy of proteins in situ. We will be able to do tomography in situ, without any staining, close to the native state and we will see the structure of the proteins and their interactions. It’s a future that brings new information and is linked to new technology. But I think classical EM is going to be here for a very long time. It’s the basis for many things we know and we have produced and will continue to produce a huge amount of data from that. In Brazil there is considerable investment in technology so I think very soon we will have a richer infrastructure. I think Brazil for instance already has a synchrotron. So it’s a matter of time and of making equipment available.

Finally, Brazil is the largest Latin American country, and one of the largest in the world. Beyond the science, what do you think makes Brazil a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

The most important thing is the freedom you will have as a scientist. I decided in my PhD what I wanted to do. If you show you are serious, you have all the freedom, without much intervention. If you have freedom, your creativity will be unleashed.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)