An interview with Leonel Malacrida

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 14 June 2022

MiniBio: Leonel Malacrida is currently Associate Professor in the Department of Pathophysiology at Universidad de la República, as well as the Head of the Advanced Bioimaging Unit (UBA) a joint initiative between the Institut Pasteur Montevideo and the Universidad de la República. He is also a manager board of Global Bioimaging and in 2018 was one of two grantees in Latin America being awarded as Imaging Scientist cycle 2 by the prestigious Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative to develop the UBA and bioimaging in the region. His long term aims include developing a strong network of Microscopy and Bioimaging in Latin America, whose purpose is capacity building, microscopy development, and scientific collaboration within the region, and worldwide. He is founder and Executive Committee of the Latin America Bioimaging network and since 2020 Scientific Advisory Board of the Africa Bioimaging Consortium. Leonel graduated as BSc in Biochemistry and PhD in Biophysics from the Universidad de la República in Uruguay. He later went to the USA, to California, Irvine as a postdoc for 4 years to the Laboratory for Fluorescence Dynamics, before returning to Uruguay as a group leader.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I remember myself as a kid, being very interested in science, watching National Geographic documentaries, and the Calypso travels by Jacques Cousteau. Everything they found in depths of the ocean was very noticing for me. I was always curious about this. I think at the time I didn’t realize what their profession really entailed, but I was curious about the world, and the nature they were watching and studying. As an adolescent in high school, I remember clearly I had a Biology teacher whom I am close friend today, who taught me Mendel’s laws and this was also fascinating to me. From then on I decided I was going to become a scientist. In Uruguay, science careers were not well recognized or well remunerated. So people often recommended that you first become a physician, veterinarian or agricultural engineer, but not directly a scientist like a biochemist. Still, this is the path I followed. I studied a BSc in Biochemistry in 1999.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy. What inspired you to choose this career path?

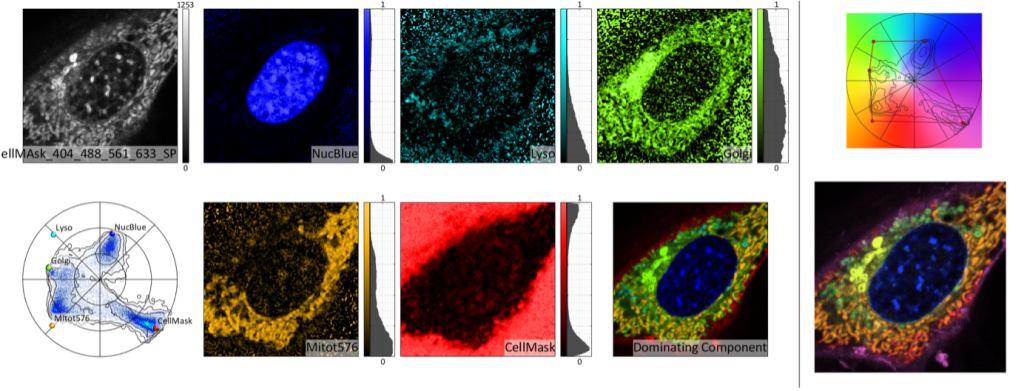

Microscopy came later in my career. Early on in my career, I focused on analytical biochemistry – HPLC, molecule purification, etc. During my PhD I found my interest in Biophysics, trying to understand pulmonary surfactant – a substance inside the lungs, within the alveoli, which reduces surface tension allowing us to breathe without the lung collapsing. My work aimed to understand how inhalatory anesthetics affect this complex system, which is made of hundreds of lipids, proteins, and other components. I became very interested in a tool, the giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs), which measure about 30-50 micrometers, and which if one uses fluorescent probes, one can see phase separation. We had the hypothesis that anesthetics produced one of the fractions – an alteration in the lateral phase organization. So because of this project, before I truly entered the world of microscopy, I had used a lot of fluorescence-based tools, but using cuvettes, and a fluorometer/fluorimeter to measure fluorescence lifetime measurements and other stationary techniques. By then I had already had experience with several techniques within spectroscopy: polarization, excitation/emission spectra, fluorescence lifetime measurements, etc. Basically, several things based on average measurements from a cuvette. It was here where I had my first encounter with microscopy. It was fascinating to realize that I could use my eyes to see many of the things that I could only imagine using spectroscopy. This truly blew my mind and I had no choice but to continue on this path. My postdoc then heavily focused on microscopy – I went to the LFD lab (laboratory for fluorescence dynamics) at the University of California at Irvine, under the supervision of Prof. Enrico Gratton, a pioneer in microscopy – a very highly recognized microscopist, particularly combining spectroscopy with microscopy. In fact, I follow a similar path to him – he started with measuring fluorescence in cuvettes for several decades, and then switched to microscopy in the 1990s. He is a pioneer in FLIM and single molecule analysis by fluorescence fluctuations spectroscopy (FCS), and other methods related with FRET, spectral, etc. In 2015, after I finished my PhD I went to his lab – I was really interested in learning more about one or more of these tools which I had used in my PhD, and it was there where I really got not only more into learning tools but also tool development. I developed some methods combining spectroscopy and microscopy too, and in tools measuring fluctuations to determine the path of molecules as they diffuse within a cell. Later, in the second part of this postdoc, I became more interested in hardware. I wanted to know how to build my own microscopes. In my mind it was always clear that I wanted to learn and then come back to Uruguay. And so learning all these skills would be vital. In Latin America all these pieces of equipment and tools are so expensive that if one knows how to make the most out of them, and how to develop one’s own, this would be a huge advantage and opportunity.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Uruguay, from your education years?

In Uruguay we have a culture that is very well established where our students egress from their BSc studies already very well prepared. I’m probably not one of the best examples. I started in 1999 and finished in 2009. But in between I did a lot of things to be able to finance myself and my studies (such as own a pizzeria). This meant a delay in my academic career. But at the same time this gave me a lot of experience. I was working as an assistant in the department of Pathophysiology in a lot of projects, where I was doing analytical biochemistry and this gave me a significant background and expertise that by the time I started my PhD, I knew what I wanted to do. I gave my PhD mentors the proposal of what I wanted to do – this was uncommon at that stage of one’s career. Usually the PI tells you what topic you will study. This had its advantages and disadvantages: I was still young and still not extremely experiences so I still made mistakes. But from those mistakes, if one reflects, one learns a lot. I think in Latin America a lot is expected from BSc students compared to some other places in the world when it comes to practical experience and scientific knowledge. In the PhDs clearly this is when a scientist becomes a professional per se though. For instance it was only at these levels when I learned how to write a project, a paper, proposals, how to propose a hypothesis and then test it, how to write results, etc.

Personally, both of my PhD supervisors were very generous: when I came and proposed the project I wanted to do – they could have said “no, we work on something else” or “we are not interested”. Instead, they helped me consolidate my ideas, and improve them and make them feasible. It was a challenging task: I wanted to work with lipids and lipid membranes from a point of view of biophysics and dynamics, for which I needed spectroscopy and microscopy. I had to do many internships because there was not a lot of this expertise in Uruguay. I first went to Madrid to do an internship at a group whose expertise was precisely pulmonary surfactant (Cristina Casals and Jesus Perez-Gil). There I learned a lot and acquired expertise in classical techniques to study membrane biophysics. Then I went to Hawaii to learn about fluorescent lifetime measurements in cuvettes. Then I went to California at the end of my PhD to work on GUVs and microscopy. I managed to consolidate what I already knew, and enter a novel area. This gave me a huge backbone as an independent researcher. To date, membrane biophysics is something I still love, and I really still love to collaborate with others.

How did you make the decision between being a group leader and a leader of platform? Was it a difficult choice?

To be honest mine is a mixed position. On one hand, I am an Associate Professor at the Department of Pathophysiology at the Hospital de Clinicas of the School of Medicine, so there I have my position as an independent researcher where I have my students and my group. On the other hand, we founded, together the Universidad de la República and the Institut Pasteur of Montevideo a Unit for Advanced Bioimaging. When we started thinking about it and designing it, I really wanted to make a turn similar to what I lived in the LFD. The LFD was a National Centre for Microscopy, where people from all over the world would come to work, and which was financed by NIH. In addition, it was a Centre dedicated to develop methods and instruments, and really promoted the development of the discipline of Bioimaging. So the core facility has this double aim (and challenge) of research and development. We have a great team, responsible for the development of microscopy tools, for contributing to research and for ensuring good practices amongst the users when it comes to imaging. We want to develop new methods and new hardware, so in this sense, we also carry out research on how to improve these tools and platform to move research forward.

About when I realized I wanted to do this: I think this wish was always there. I was always conscious that I wanted to lead a group one day. Above all, I was very inspired by some group leaders or teachers I had during my career. I mirrored myself in people I admire. How this came to be is a different thing. Despite the plans that one designs in one’s mind, destiny takes us into paths that sometimes we don’t imagine. Sometimes we force things into place, but it doesn’t work like that. So, between the effort that one has to invest to achieve what one wants, and the unexpected turns that destiny sends us, one has to find a balance in order to be happy and feel accomplished.

About leading the core facility: I love collaborating. When I became director of the core facility, I started with 4 aims:

- Provide service.

- Develop tools and methods in the area of microscopy and spectroscopy.

- Develop curiosity-driven projects, driven by biological questions. Here I have a few students on specific projects, but the majority of projects are collaborations. Since I came back to Uruguay and I am leading this unit, it happens constantly that a user has a concrete question, and from the discussion, new projects arise. This is great because we can develop new methods that come up from those questions.

- Scientific dissemination through communication, and education and training.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Uruguay?

Yes, during my career, and because of the internships I did and my postdoc, I met other Latin Americans. I got to know Chileans, Argentinians, Brazilians. When I went to the USA I maintained these contacts. It all started in 2018, when we started a project of bi-regional cooperation between Uruguay and Mexico, in which we came up with the project UruMex Microscopia led by Dr. Andres Kamaid, and where Christopher Wood for Mexico and myself for Uruguay, are co-PIs. This financing was different: it was not to do research, but to develop capacities and communities. I was at the time coming back from the USA – there was still no agreement between Institut Pasteur and Universidad de la República. We started learning that National Laboratories has developed really well. Christopher Wood leads the National Laboratory of Advanced Microscopy in Cuernavaca, and we had a lot to learn from them. Within this project, there was one aim: to facilitate the creation of a Latin American Bioimaging Network. In this context, we dedicated some money to make a regional funding event that would involve researchers from the region. There were several initiatives before, all very valuable, but this network had not been consolidated. Between Christopher Wood, Andres Kamaid and myself, we started identifying colleagues across the region to put together this network of Bioimaging. I must say we received huge support from the International Bioimaging community. And at Chris Wood’s invitation, we started participating in Global Bioimaging – it has been a huge support to Latin American Bioimaging so we could start developing targeted activities and networking events. We have organized several events: some on interactions within the region, for which we wrote a Focal Plane article (https://focalplane.biologists.com/2021/10/27/latin-america-bioimaging-a-network-to-advance-bioimaging-in-the-latin-america-and-caribbean-region/). Another, where we made a link with Euro Bioimaging – Latin America Bioimaging, and organized a congress on exchanges regarding research infrastructure between both continents. More recently, another event about the projects financed by the CZI initiative, especially targeted to Latin America, Africa, ex-Soviet countries. We are very happy that Latin America was able to receive huge amounts of funding which will allow us to establish local resources, to facilitate regional cooperation, and specifically consolidate our network here and have a working plan for the next 3 years to develop all levels of Bioimaging in Latin America, and capacity building: students, technicians, core facilities, etc. The most challenging thing is that we have to build critical mass so that we can achieve bigger things, otherwise without enough input things can fall apart. We all have our own activities, and we devote our time and resources to this additional task. Everyone is giving 200% to make it happen, so we can’t do it in small numbers forever because we all have our obligations and deliverables within our own institutions.

You mentioned that when you were doing your postdoc abroad you always wanted to come back to Uruguay and contribute to the development of science in your country. How was it for you to study/work abroad, and how did you figure out how you could “give back” to your country?

Perhaps it’s an Idyllic or romantic idea, to go abroad and learn, and then come back and bring with me knowledge, technology and “know-how” that did not exist here. I always wanted to mix spectroscopy and microscopy. This was an area barely explored in Uruguay. The tradition here in the country was electron microscopy, with the legacy of Professor Clemente Estable, who was the first researcher in Uruguay who managed to consolidate an institute with the first electron microscope in Latin America back in then in the fifties.

Since I left Uruguay, I knew I wanted to come back, for two reasons: one is, I left with a tenured position in the Department of Pathophysiology, so I had the formal and moral obligation to come back. Everyone made a huge effort for me to be those 4 years in California so it was my duty to return, and “give back” what I learned while abroad. Also, while abroad one learns a different way of working, especially in more developed countries where the rhythm with which one can perform science is completely different. Here in our area (in Latin America) one has to be able to do a bit of everything so that things work. While I was there in California, I only had one role: to be a postdoc doing science and collaborating in the activities of the group. Nonetheless, my experience at LFD was very enriching: I was able to learn what was a core facility, and this helped me to set up the 4 aims I previously mentioned.Altogether, I think if we have clear objectives in our minds – I am an optimist – I think we can achieve our goals.

You clearly have an enormous commitment towards training the next generation of scientists and microscopists. Can you tell us a bit about what drives you and how you feel this vital aim of yours has progressed through your career?

It’s a vision guided by my optimism – I feel. Even as an optimist I didn’t envisage that things would go as well as they have, or would have moved forward in the way they have. I am truly very happy about this. In particular, for me, having received this first CZI grant as an Imaging Scientist in 2020 was a huge support and a huge surprise too. It allowed me to join another 20 imaging scientists worldwide. Sadly, I was the only South American and one of two Latin Americans (together with another Mexican scientist). There were no others. But since then, I found an international community that was very interested in promoting the development of bioimaging worldwide. Since then, until now, I’ve always had great input and initiatives to achieve what we have proposed ourselves to do here in Uruguay.

Regarding core facilities, I feel this is paradigm-shifting. World-wide it seems to be well established what the role of core facilities is: to centralize knowledge and infrastructure, to recruit (and centralize) personnel who can make the most out of this technology, and centralize resources that allow us to expand resources or develop new technologies. In Latin America we are a bit behind in these goals: the financing schemes, regional cooperation, etc still do not always consider within their plans, core facilities – neither at country nor at regional level (i.e. Latin America). This is a limitation – I feel if we look at international models, they are already great models for the development of research infrastructure and what brings the most benefit to research.

Beyond this, simply declaring that a core facility is open access doesn’t solve many problems: there are still difficulties and impediments way above simply being able to come to the core facility and perform an experiment. Namely, having the adequate training and experience to set up a correct experiment that uses the most out of our resources. I will quote here a phrase of Leong Chew, from HHMI at Janelia Research Campus who says that the fact that technology is “open” or accessible to everyone doesn’t mean that it access is equitable. To achieve this equity, we all need to put extra effort, which luckily we can do here. We are working on programs to educate educators (not only students). The objective is that they will be able to adopt at least one tool into their core facilities. We think with this model we will reach more regions and more researchers here. Above all, when targeted to core facilities, the knowledge will remain in the labs and in the region, which is different to the expectation and reality with postdocs (who often change labs and move countries). Part of the financing from CZI we will be able to guarantee a group of around 6 people per year to do an internship here, with the premise that this will lead to stable collaborations later on. Altogether, for us equitable opportunities are a priority. Then we can move away from access being restricted to specific niches with expertise or money, but whose expertise doesn’t go beyond their lab.

Who are your scientific role models (both Uruguayan and foreign)?

I have many. All my supervisors, who taught me how to be a scientist. Three people in particular had a huge impact- my BSc and PhD supervisors Hector Píriz, Arturo Briva and Ana Denicola taught me the elementals and rigor of the scientific method, and also more human abilities: how to collaborate with others and how to be honest intellectually speaking. As a reference in fluorescence and microscopy people who have also left a huge mark in me include David Jameson, a great friend of mine and an expert in the area of fluorescence; Luis Bagatolli (who recently passed), also a great friend who was a huge influence due to his expertise in the area of membranes microscopy and science (all my gratitude, respect and memory of him will last within my for ever); and perhaps one of the people who most influenced me is Enrico Gratton who was my Postdoc supervisor who had the right sensibility to challenge you enough each time, to make you better, without discouraging you. He taught me to set myself goals that allowed me to walk further than I knew I could, but never was the objective too far away that the objective was unreachable. I think this comes with experience from many years working with human beings ☺ it’s very difficult to achieve. It is an extraordinary ability to realize (as a mentor) how far one can push someone to progress and develop capacities they didn’t know they could. Academically and intellectually, and as a human being he is the person who most has challenged me in my career, in a positive way. Enrico is the great model for me to follow.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

I love everything. I am biased towards optical microscopy – I love fluorescence microscopy as a tool. I think my work as a postdoc allowed me to develop some fondness towards FLIM and hyper-spectral imaging. I find both of them extraordinary ways to measure parameters to gain valuable information regarding a fluorophore: who is it “talking” to and “interacting” with, or what exactly is happening to it.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

Many many times. I love to see with my eyes (beyond sitting at the computer). I think the eye is a very sensitive detector: to colour, brightness, changes in polarization, etc. Perhaps the moment I remember most is the first time I was working with GUVs – you need a lot of “unspoken” skill to work with them. I managed to see one and phase separation with my own eyes. I still get excited when I see this.

And then, every time we develop a new method or tool, and bring something that was only an idea and give it life, it’s a sensation that I can’t describe.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Uruguayan scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

The first thing I would say is go to conferences and congresses: try to establish links with people of your same level within the country and internationally. This will allow you to learn more about your own project and about science in general. Immerse yourself in as many things as possible, not just what you like. I think having ‘horizontal’ knowledge is very enriching.

Another things is, as I started going to congresses (in particular the Biophysical Society), my wish or my objective was to meet people whose papers I read – the super-heroes behind the papers I was interested in. I was lucky to meet many of them, among them the one who became my postdoc adviser. But a senior scientist once told me something that helped me a lot in my career: he told me “when you attend conferences and congresses, interact with other PhD students and postdocs- people of your age. Try to meet people who are at the same stage as you, and ask them about their problems and experience, not just in science, but try to understand what are the difficulties others have to see if they are the same as yours. Moreover, these young colleagues, in the future, will be your colleagues – long term ones. If you know each other since your youth, interactions will be much easier once you are a group leader or in a higher position”. This helped me enormously – I am great friends with many people now, because of this. So my advice is indeed, it’s ok to want to know the super stars, but your same age colleagues will one day be those super stars (and your direct colleagues and collaborators).

Beyond the science, what do you think makes Uruguay a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

Uruguay as a small country, has a lot of good and bad things associated with this. It’s small and therefore finite (we all know each other, so we know what the expectations are). On the other hand, Uruguay has paved the way of great scientific development over the last decades. This resulted in a solid community in various areas of science. There are great scientists here who have a lot of potential and value equal to other groups worldwide. Because it’s a small country, a difficulty is that we might not have as many resources. So we have to be resourceful! We have to re-invent the wheel sometimes when we don’t have the resources to just order any reagent or any piece of equipment that might be easily available in more developed countries, but not equally accessible in ours. While this might be a hindrance, it is also great – it triggers resourcefulness. Of course there has to be a balance to make the call on up to what limit it’s worth re-inventing the wheel or really just buying a new one.

The biggest difficulty from the imaging perspective is perhaps that we are still on our way to consolidate some areas in order to attract international talent toward some areas, such as hardware development, image analysis and so on. Many students in the region (in Latin America) look to the global North as a place to migrate to, but perhaps not Uruguay. Perhaps in a few years, with our aims and current efforts, Uruguay will be an attractive place too. I think we are setting up new infrastructure and methods and opportunities to advance science and make this possible. On a personal level, life quality is wonderful – we have public education, public health, safety, etc. We have a wonderful weather in all seasons.

(2 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

(2 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)