An interview with Federico Lecumberry

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 5 July 2022

MiniBio: Federico Lecumberry is an Associate Professor in Signal Processing and Machine Learning at the Department of Electrical Engineering at the Faculty of Engineering of Universidad de la Republica in Uruguay. He is also an Associate Researcher with the Advanced Bioimaging Unit of Institut Pasteur de Montevideo. He completed his BSc, MSc and PhD degrees in Electrical Engineering at Universidad de la Republica in Montevideo, Uruguay. His research interests include Signal and Image Processing, Computer Vision, Machine Learning, Biomedicine, Medical Imaging, and Cryo-EM. He is a member of IEEE Signal Processing Society; National Researchers System in Uruguay; Uruguayan Biosciences Society; and Uruguayan Society of Microscopy and Imaging, as well as a researcher of PEDECIBA – Mathematics. For a complete biography visit https://iie.fing.edu.uy/personal/fefo/

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I began my career as an engineer actually – I did a BSc in Electrical Engineering – more directed towards communications until I was about 23 years. What was attractive about this career were the job prospects and applications, so until then, it was all about this. Around this age I started working as a teaching assistant at the Institute of Electrical Engineering (Faculty of Engineering, Universidad de la República) (https://iie.fing.edu.uy/) and only then saw the more scientific aspect of my profession. This path was slightly different to other degrees which are more clearly directed towards academic science such as those from the Faculty of Sciences in Biology or Physics or Mathematics. I was always attracted to science though – growing up I used to watch science-related documentaries and programs. I remember the program of Carl Sagan, ‘Cosmos’ which was fascinating, among others. But only when I began working as a teaching assistant did I realize I could indeed contribute, with my skills, towards different aspects of science, and particularly biomedicine. In my PhD, I started working with specific microscopy types and it was here where I discovered my passion for science altogether. I still find it hard to say I’m a scientist though, because my training was really all about engineering. But I do admit that with time I have acquired a way of thinking, addressing problems and of applying the scientific method – which ultimately defines us as scientists. In this process, my interaction and collaboration with researchers from the Faculty of Medicine and the Institut Pasteur de Montevideo were key. I have also found a way to develop fundamentals and methods that are part of the scientific process, with my expertise and skills derived from my engineering background. To answer your question, it has been a process: I didn’t start wishing to or defining myself as a scientist, but rather found myself immersed in this path as I progressed and evolved in my career.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy and image analysis and medical imaging. What led you to choose this specific career path, and how has your own career progressed within this path?

All throughout my career, since studying Electrical Engineering, I have been extremely interested in Signal Processing, and this has been the core of my work. During my BSc, Signal Processing applied to communications and images was the orientation of my work. During my MSc and PhD I decided to do Image Processing and Machine Learning, back in 2001. The latter is now a very fashionable discipline, but it has been done since a long time – at our institute we have been doing it since around 1999 (with the first course on Pattern Recognition). We’ve been teaching this for 23 years, and handling projects for academia, industry, etc. Although I feel I’m slightly an outsider because of this background, I feel extremely welcome in the biology and biomedical scientific community. I feel I’ve been privileged in being able to apply my skills to a very wide and varied range of projects. In 2014 I started a five years group at Institut Pasteur Montevideo (https://pasteur.uy/en/innovation/laboratories/). Before this, I had already been in contact with people from the Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas Clemente Estable (http://iibce.edu.uy/), where I knew other scientists and was already aware of the skills I could bring to the table. My work has been in a way a feedback loop: I am able to provide services/collaborations to other groups that focus on biology and biomedicine, and by doing so, we are able to develop new fundamentals and methods in our discipline. From the collaborations we are able to identify the tools that are missing and the gaps that must be bridged from our side of expertise. I have been within this community for a bit under 10 years, so I am, in a way, a newcomer. But nowadays, with science being more quantitative than ever, and our capacity to generate extensive amounts of data, to ask ever more complex questions and to address them, I feel we have an enormous field we can contribute to and for which our expertise is relevant.

At Universidad de la República, there is a division called the ‘Interdisciplinary Space’ which promotes projects and activities that bridge disciplines. A year and a half ago we submitted a proposal which has now been approved, on a project to develop the ‘Centro Interdisciplinario en Ciencias de Datos y Aprendizaje Automático’ (CICADA) (Interdisciplinary Centre for Data Science and Machine Learning) (https://cicada.uy/). We are a group of various engineers (electrical and computational), mathematicians, as well as biomedical scientists focusing on genetics, human reproduction, neurodegenerative diseases, neurosciences, etc. From these latter points of view we have members working on Machine Learning, Signal Processing, Computer Vision, Natural Language Processing, etc. So with funds from the University, we are developing this interdisciplinary research. This all arose because we identified that modern data science is necessary in the toolkit of any modern scientist (regardless of discipline or area of expertise). So we promote the generation of such abilities among the scientific community of our University. Universidad de la Republica harbours a very high percentage of Uruguayan scientists in the country, and produces an equally high percentage of the scientific output of the country too. So the Centre we created has a large reach not just within the University but beyond its borders too. We are putting great effort into knowledge transfer – we organize summer schools (or rather, spring schools) where we aim to bring together scientists from a ‘non-quantitative’ background to provide this training on data science.

Regarding my own work, I personally like to be involved in projects from the beginning: to sit down with our collaborator from the pure science background (i.e. biologist, physicians or other), understand what the question is, understand the system, and get really an overview of the problem we are addressing to see: a) how we can answer the question; b) whether we can propose a different question; c) whether we have an alternative way of addressing/exploring the data. I don’t like the approach where a collaborator just gives me a USB key and tells me what to do. I want to be part of the whole research process. I think CICADA allows this approach. Within CICADA, I have my research interests – I have IMAGINA, which is the name of my group (BioImage Acquisition and Processing Group (http://imagina.science/)), which I founded together with a colleague of mine from the Faculty of Medicine. This group is the one interlinked with the microscopy community – but I am just as excited to investigate pixels arising either from mitochondria in a microscopy image, or a star from an astronomical image ☺ We can always ask ‘pixels’ any and all sorts of questions.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Uruguay, from your education years?

I studied in Uruguay my whole career, but I had the chance to study abroad at different stages of my career. During my MSc I was at the University of Granada for about 6 months, in Andalucia, Spain. In my PhD I was at the University of Minnesota for 2 years, in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, and did research visits to the NIH in Bethesda. I really like my country though, and for this and family reasons, I am settled here.

From my training, I had some scientific projects from the beginning. I feel my training as an engineer didn’t limit me, which is why I had the option to follow whichever path I wanted after I finished. In terms of international exchanges, this has become a possibility in more recent years, which opens a whole new door and prospects. Currently in Electrical Engineering there are many opportunities for studying one year of your degree abroad, in Europe. However, there is a very big problem in Uruguay with young scientists with excellent training who must emigrate to pursue their interests. This brain drain is terrible for the investment involved in training a scientist for the country, and in some way marks the excellent quality of training achieved.

Can you tell us a bit about your path, and how did this shape you as a microscopist/image analyst?

In the last year of my PhD I became a faculty member. I didn’t do a postdoc. During the last section of my PhD I had access to an Assistant Professor position, and so once I graduated and after my last internship abroad, I just went back to occupy this position. To give you an idea of numbers, out of 70 graduates in Electrical Engineering, only about 10 people of my generation went on to join academia, but we did this at our own pace. Some joined directly after the BSc (immediately joining a MSc or PhD program); others (like me) took a slightly longer path. I started my PhD in 2007 and finished in 2012. So I was 7 years doing other things before doing a postgraduate degree. Only from 2015 I hold my current position as an Associate Professor. In those 7 years, however, I was already doing research and participated already in a wide variety of projects. I have been teaching since the year 1999 – I love teaching – in fact it was due to my interest in teaching that I joined academia as a scientist.

Throughout your career, did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Uruguay?

I have been lucky. All throughout my career I have been able to interact with other Latin American groups. Collaborations are not very constant, but there is a network and collaborations do exist, especially with Chile and Argentina. In microscopy, the strongest collaborations are with Chile, Argentina and Mexico. In Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence, strong groups are in Brazil, and Colombia, too.

An important phenomenon that has been happening over the past couple of decades is that many young Latin American scientists that went abroad for training, are coming back to set up their own independent groups here. Argentina for instance, has a very strong repatriation program, which was very successful. As a consequence, very close to us, we have several groups that have all this very diversified knowledge from technology applied all over the world. A few years ago, in 2014, we wrote a paper on how Latin America was doing at the time in terms of research on “Big Data”. We used indicators from Scopus and affiliations, and we investigated the networks of scientists within Latin America and with other world regions. (See publication in this link: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031320314001575). This was very revealing! Beyond my own specific experience, I think great efforts are being done in Latin America to promote collaborations. Leonel Malacrida for instance, and everyone involved in Global Bioimaging and Latin American Bioimaging are doing an excellent job in really strengthening these networks. This is becoming revolutionary in the region, and placing us in the map.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Uruguayan researcher, working abroad?

I would say no. Academically I didn’t face challenges either in Spain or in the USA. I was surrounded by foreigners. In Minnesota my PI was Uruguayan, and my colleagues were from India, Iran, Israel, France, Germany, Spain, Brazil, etc. We became close because we all played football too – it was 2008 and Spain won the World Cup so this was an excuse to get together. In academia however, there are sometimes situations where one can feel that one is treated differently, but luckily, these situations were not many.

Who are your scientific role models (both Uruguayan and foreign)?

☺ This is a great question. I think my role models are the PIs I’ve worked with. I was lucky always to have been part of groups with very good leaders. No one is perfect, but I was able to learn from all of them from their capacity to build a group, to make others grow, to set up projects and address scientific questions, to reach goals, and how to get each student to reach their maximum potential. In some way, now that I am a group leader myself, I’ve tried to mirror the example that my group leaders gave me, and which I was so lucky to have.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Uruguay, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career? As a group leader, how do you address this important topic?

During my degree we were about 70 people, out of which only less than 10 were women. This was back in 1996. Electrical Engineering is one of the degrees with the least women. Computer Engineering and Chemical Engineering have more women in comparison. But this proportion has improved with the years – albeit there is still no gender balance, and I do see there is a glass ceiling that women face in their professional and academic careers. At the Universidad de la República we have categories (grades) in which we are classified as researchers and teachers, based on our career progression. Grade 1 is an undergraduate student, while Grades 3 to 5 are the highest ‘ranks’ (Assistant, Associate and Full Professor respectively) depending on the department – and at the highest levels, the majority are men. And a similar situation happens at the National Researchers System. At least in the Faculty of Engineering, there are programs to promote the involvement of girls and young women, such as Chicas TIC (Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación) (https://www.fing.edu.uy/proyectos/chicastics/).

Here we aim at showing that Electrical Engineering is for everyone and to expose them to what this career is – to remove the myth that this is a career for men. We are still far from having gender balance though, but there is some improvement. I feel there is not just a disbalance in terms of gender, but also other minorities, which should be addressed. I also feel that when we do science communication that reaches the general public, we must put an emphasis on the message that science is for everyone.

In 2019 we organized the first Latin American meeting in Artificial Intelligence, Khipu (https://khipu.ai), whereby we invited the experts in the area from across the globe to Montevideo. We had over 300 students, and we had special sessions discussing gender disbalance. One was called ‘Women in AI’, where we emphasized the work of women who have contributed to this field through the ages. We wanted to provide role models and show that this is possible. And for Data Science at least there are a lot of movements from different minorities: ‘Women in AI’, ‘Latins in AI’, ‘Black in AI’, ‘Queer in AI’. These groups are bringing attention to the relevant gaps (gender, race, etc.) to the general Artificial Intelligence community through workshops, conferences, etc.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

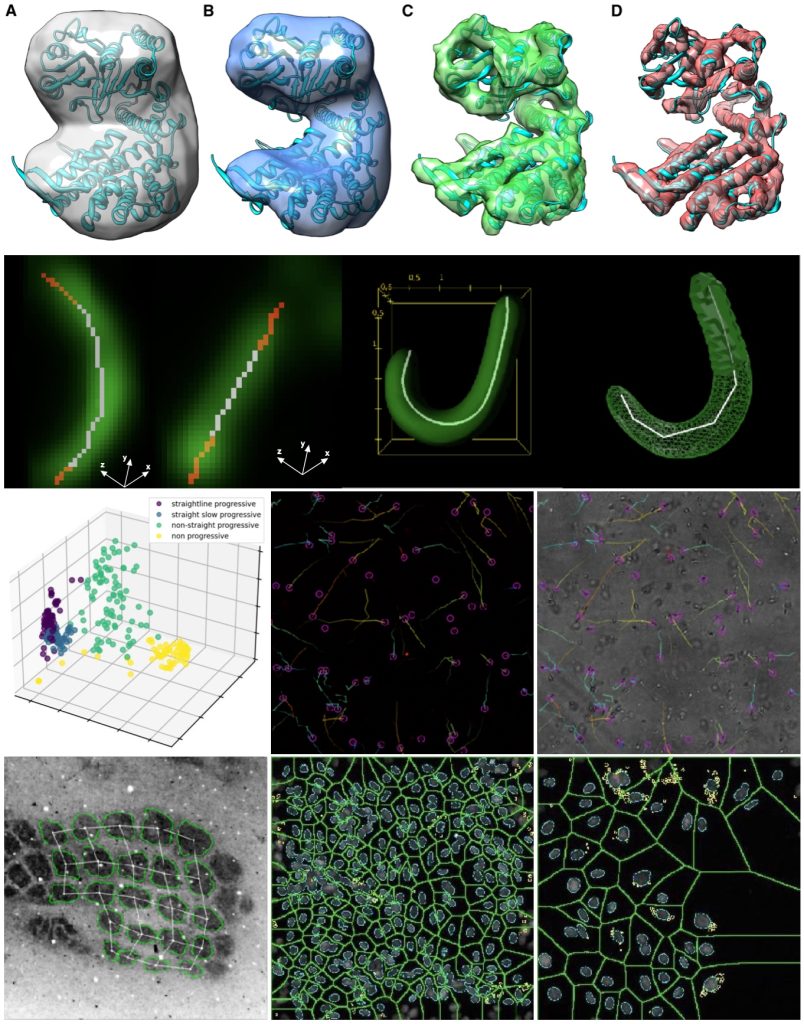

Of course! I love cryo-EM – sadly in Latin America only Brazil has this technology – it’s extremely expensive and almost artistic in the specimen preparation. This is what I did during my PhD, and the main idea was to tackle cryo-EM from an engineering and technology point of view: the challenges for signal and image processing. I find this technique fascinating, and particularly the applications it has. When I came back to biology, it was due to my interest in cryo-EM and it brought me internal peace to close this cycle – when I noticed what I could bring from my own background in electrical engineering. Anyway – I can speak for hours about cryo-EM. During the last decades it has had a revolutionary progress, and involves Nobel Prizes and all sorts of accolades.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

Part of my PhD was all about proposing a new way to process data derived from cryo-EM, which allows us to obtain a lot more information from the images. We published this in 2012 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23217682/), and it is something that is still bringing lines of research and possibilities of projects and collaborations. I remember we were walking through a parking lot at the NIH back in 2009, and we had the eureka moment where we came up with this idea. We uncovered geometrical constraints that arise from the form of data acquisition that were not imposed during the optimization. To bring these geometrical constraints to data processing is the ‘eureka’ moment.

We have had other moments though. I mentioned before that I like to be involved in projects from the planning step already- the image formation step/data acquisition step, is a step where technology is involved. To be able to model these technological phenomena and to be able to modify them (in Engineering we model reality so we can control or modify it), allows us to propose new methods and bases for image processing. This allows us to improve image acquisition methods, resolution, image quality, etc. This is my preferred activity as a scientist, and what my group focuses on. In general, I also consider eureka moments when ‘numbers tell us a story’. Finally, my other eureka moment is to see someone from my lab become a fully formed scientist, say for example a PhD defense: you see a young student become a mature scientist and this is priceless. And as I love teaching, I also have eureka moments as a lecturer. In my lectures, I explain the fundamentals of modern technology, and the eureka moment comes when you realize ‘it all clicks’ in the brain of your students. This is very rewarding.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Uruguayan scientists? and especially those specializing on image analysis/as image analysts?

Do it!!! Image analysis is at the crest of the wave at the moment. There are many possibilities, both in Uruguay and abroad. I indeed have had many students come and ask me this question, and they have ended up working in major companies. Advanced skills in Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Signal Processing, and in general Applied Mathematics are super well remunerated and necessary. Unemployment indexes for these areas are in negative numbers. The most innovative aspects of our profession will be very close to your own work. Also, the area as a whole is very open: open code, remote work, etc, which has ‘shortened’ the distance among us. Moreover, we need more people in this area!!

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy (and image analysis) heading over the next decade in Uruguay, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think Data Science must be taught and will become part of the basic toolkit of any biologist. Currently for example, all biologists must know statistics – they must know how to interpret results, how to know significance, how to calculate this, and so on. I think gradually the same will be true for programming and coding. We are living in an age of information (which can be precisely mathematically defined), applied mathematics and its tools, whereby we must all learn how to use such tools that enable us to answer our questions, and adapt these tools to existing methods in our fields. Equally important will be to put further focus on interdisciplinary work/collaborations. But not everything can be based on collaborations – I think modern scientists will have to learn how to use these methods on their own. This has to be fostered throughout one’s entire career. In CICADA one of our challenges is how to provide tools to non-mathematicians/non-data scientists, which require knowledge/skills in programming. For instance, speaking specifically about imaging and microscopy, there are various pieces of software that are very user-friendly, which allows scientists without any knowledge in programming, to do image analysis. An example of this is ImageJ, of course. Everyone who has ever done bioimaging knows ImageJ, which at its most basic level, is like Photoshop for science. But this tool is much more complex, and allows for script generation, macros, automation, etc. Maybe some scientists don’t know all the things one can do with that software, and it’s important to break this barrier, to make the most out of this tool. This is just one example.

However, to include programming as a subject in BSc degrees is proving challenging, simply because the choice of degree, at least currently, is guided a lot by ‘I like maths’, or ‘I don’t like maths’. If the former, we choose Engineering and quantitative science. But programming cannot be done without Mathematics. I feel a more robust training for all scientists will be important, including Mathematics and Programming. We need to get rid of this myth that ‘Maths are difficult’.

On a different topic: Microscopy is reaching the age of ‘build your own microscope’. Innovation in microscopy is moving towards open microscopy, and this is pushing boundaries in science, with modular microscopy, and better links between hardware and software which can be tailored for each researcher’s needs rather than relying on commercially available microscopes. Moreover, many fluorescence super-resolution methods are tightly linked to signal processing, and this link has enormous potential. It is the starting point for a lot of innovation.

From my discipline, low-cost material to promote the integration of software and hardware is allowing for a lot of flexibility. This is reaching world regions where it will be most beneficial. And if we have human resources capable of bridging these gaps in knowledge, the potential is extraordinary.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Uruguay a special place to visit?

The level of science in Uruguay is very good, however the scientific community is very small compared to other countries. Since finances are a challenge here, we are easily capable of doing “frugal” science and we are resourceful in the way we do science, within a very supportive community. In Uruguay we don’t have a lot of natural challenges (no earthquakes, no extreme weather, etc). Uruguay is described as a slightly undulating plain, and in a way, we have a character that fits this country. Uruguayans are easygoing. There are a lot of natural wonders, beaches, countryside, etc, which is essential for a good work-life balance. We also are fortunate that we enjoy a good measure of political and social stability compared to perhaps other countries in the region, so life is relatively peaceful. In a way, this stability also promotes that our scientists abroad to want to return, therefore strengthening science in our country.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)