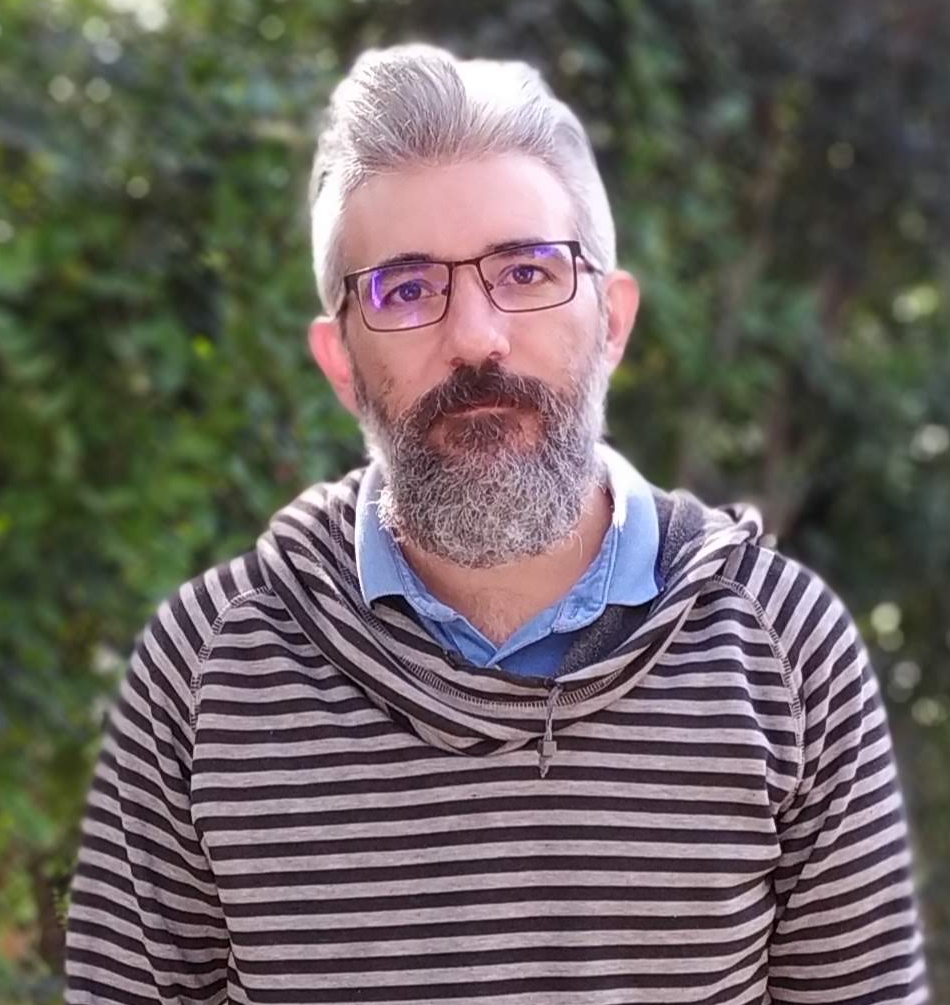

An interview with Rodrigo Vena

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 27 September 2022

MiniBio: Rodrigo Vena is a core facility member at the Bioimaging Unit of the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology in Rosario, Argentina. He specialized in Optics, and is in charge of optical microscopy. Rodrigo is passionate learner in all things related to microscopy, and strives to keep up to date with the advances in the world of microscopy. With this aim, he has trained in several local courses in Argentina, at the Zeiss campus in Jena, Germany; at EMBL in Heidelberg, Germany, and at Institut Pasteur in Montevideo, Uruguay. His mayor area of expertise is in confocal microscopy with more than 10 years operating systems. He has acquired knowledge and expertise on novel methods including light sheet, Brillouin microscopy, and image analysis, enriching his extensive expertise in other optical imaging methods.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

It’s a long journey, right? Actually, I never thought about being a scientist. Although in reality I don’t know if I’d call myself a scientist. I’m a member of a Microscopy platform, and I provide service and technical assistance relative to microscopy, to all researchers and PhD students. I give advice whenever needed, on the different microscopes, and what the most suitable technique might answer their research questions. I imagine that nonetheless, one carries curiosity in one’s soul: a need to answer questions that no one has addressed or asked before. When I was a child I loved putting things apart to “see what’s inside”, and try to figure out their mechanism. I remember vividly that during the summer holidays, when I didn’t have to school and my parents weren’t at home I would go to their room, and they used to have blinders – one of those that have periodic holes in them, and light would pass through them, because their window faced North. I would play with them – I would beat the mattress to see the reflected beams of light coming through the blinder holes. Also, my mom used to have a makeup mirror, which she inherited from her grandmother – which she still has, by the way. It was a faceted mirror at the edges, so I would play with it to see changes in the reflected light. I found light fascinating! And as I say, I would always be building and unbuilding toys. I think this was already guiding me in my scientific journey. But I would say it’s curiosity that guides your path. I ended up studying Optics when I grew up.

You have a career-long involvement in cell biology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose these paths?

I lived all my life in Rosario, Argentina. Now I live in Roldan. Rosario is probably the 3rd largest city in Argentina. And in Rosario there is a degree called ‘Technical degree in Optics” (Técnico Universitario en Óptica). Actually, I wanted to study Photography for a long time. But the degree in Photography in Rosario has a focus mostly towards the artistic aspect of Photography. I wasn’t so fascinated with the artistic world, but rather on the technical part. After studying one year of the BSc in Psychiatry – and quickly realized this was not for me – I entered the degree in Optics. In it, surprisingly, I studied 4 years of Photography. The career had 2 main branches: Optics applied to Ophthalmology, and Optics applied to Instrumentation. I always found the latter more attractive – this included all instruments that use light to measure something, including telescopes and microscopes. So I chose this path. Also, there is a dissertation one has to do at the end of the degree – the project is the last step in your degree before you can graduate. I chose to do a Newtonian telescope from scratch. I built all the little pieces – it was really from zero. It took me a little more than a year, but in addition to the abilities and the experience, I gained life-long friends and colleagues during this project, including the professors and colleagues. Anyway, I had a start in my career with Astronomy, and ended up joining the field of Microscopy. I still keep my telescope, and I take it out every now and then.

How I ended up in Microscopy was also a bit by serendipity. I never imagined I would end up in this field. My supervisor during my undergraduate degree had a niece who worked at CONICET – the national Council of Science in Argentina. During a family reunion, she told my thesis director, Daniel Galeano, who used to be a leader in instrumentation, that they were looking for someone to handle a confocal microscope. Daniel called me and told me about this opportunity. I was in fact looking for a job at the time, and he suggested I apply. I didn’t even know (until that point) that there was a confocal microscope in Rosario. I had learned about confocal microscopes during my degree, but I had never seen one. I prepared my CV, I sent it, and was called for an interview. I started working in a probation period, and then I stayed. In October it will be 12 years since I joined. It’s as if that job was made for me, and it was love at first sight with the job. The person who hired me guided me for a short period of time, and then it flowed very well. It was magical. And ever since, as it often is in microscopy, updates and training never end. You have to stay up to date with all the advances, otherwise you quickly become obsolete. Especially if one considers the last 10 years – the amount of progress that has occurred in microscopy, the amount of new techniques and methods, and new applications, is enormous, including the super-resolution revolution. Other revolutions include single plane and light sheet imaging. It’s not difficult to become fascinated with microscopy. I think the first time I looked down a microscope, it was a feather, and it was a toy microscope – it belonged to one of my cousins, and she hadn’t opened it. I asked her what it was, and looked down at this sample and loved it immediately. And have loved it all along. After all, the gap between Microscopy and Photography is not huge. I ended up being a Photographer of small things 🙂 And I love it. I think when my time comes to retire, I probably won’t. I really love what I do.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Argentina, from your education years?

I think the quality of teaching is outstanding. My thesis director, who helped me when I was building my telescope, was very inspiring. When I was a student I didn’t always attend all classes 😛 I used to skip some every now and then, and I approached who would then become my dissertation supervisor. One of the classes was on optical instrumentation, where you basically would cut glass to build instruments. I hadn’t attended the lab a lot, and in the last few months of the year, I told my (then future) supervisor (Daniel Galeano) that I needed to catch up with all the work that I had missed, in those few last months. He said it was impossible, but I assured him I could. He agreed that I could come to do the practicals, and gave me a chance to use the labs freely, to be able to complete them on time. Eventually, we became close friends. Anyway, something great about Argentinian education, in my experience, is the chance of forming close mentorship-based relationships. Their doors are always open. Moreover, education is public and free. Although this is not always valued, I think this is vital. If the teachers realize you are interested, the teachers really invest in you. When I finished my degree, I worked for some time in Daniel’s workshop, focusing on optical instrumentation. This was a fantastic opportunity, where I learned a lot.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a researcher involved in microscopy?

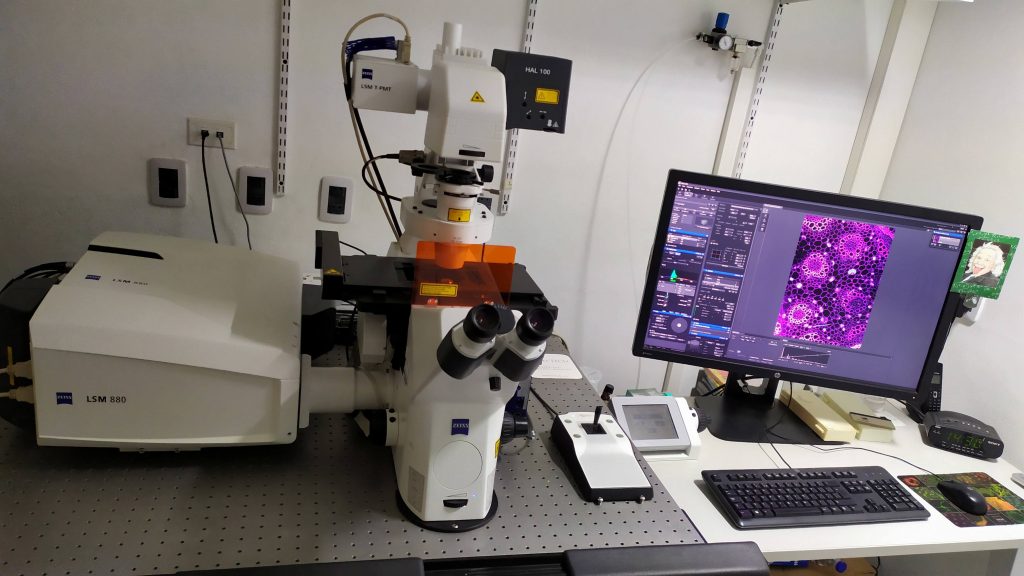

I work now at the IBR (Instituto de Biology Molecular y Celular de Rosario), and 5 years ago we had the chance to buy a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM880 microscope), and my job is to maintain that microscope. A deep knowledge of the microscope has allowed me to get involved in several projects. During the COVID pandemic, there were limitations to the number of people that could be in each room for the confocal microscope this limit was of 1 person, so this impeded that both, myself and the users could be in the same room at the same time. The LSM880 was the only operating confocal microscope that remained operational during the pandemic. So, instead of the usual practice, which is that me and the users sit together at the microscope to work on the samples, I worked alone during this time. The users would tell me what they needed and what they were looking for and I tried my best to help them with the imaging parts of their projects. In summary, my job is to maintain the microscopes, organize the schedules for usage, prepare the rooms and maintain them, and so on. You might ask yourself why I get so involved with the projects, while in other places of the world the more conventional approach is that the Head of Unit, or the staff members of the Microscopy Unit train the users so they can do their experiments themselves. But here in Rosario we need to do it differently for one main reason: if a user mishandles a microscope and any part breaks or becomes damaged and needs repair, while in other parts of the world this might take a short time, or alternative equipment is available, here in Rosario, repair and service can take many many months, and we have no alternative equipment that can replace this one in the meantime. This would have a very deleterious effect on research, which is a risk we choose not to take. It’s a different reality.

Regarding career progression, I think Argentina is similar to other countries – for core facility staff, it’s only recently starting to change. I’ve been doing a rather similar job since 10 years. However, I’ve been lucky to be in an institute where the demand for microscopy is very high, and the teams are very collaborative. So I’ve had the chance to get involved in a lot of research projects. Also, I’ve got more chances to get involved since I started doing image analysis and image processing too. Here in Argentina you have a chance of progression that is inbuilt in the core facility career: there are 2 levels, with 4 sub-levels in one, and 3 the other. But if you think about it, eventually it gets stagnant. It can be a repetitive job, but I also have the impression that in terms of learning, it’s a personal choice to some extent. If you push yourself to learn more, it’s possible to learn more. If you choose to stay at a comfortable level, you can also do that. But of course the more you learn, more doors this opens in terms of progression, and in terms of the amount and scope of projects you can get involved in. In fact, I am included as an author in several papers of various groups because of my involvement, but I know this is not everyone’s reality. In some places, members of core facilities are not included as authors, or their input is not required (beyond the technical or training input). I have been fortunate to be able to get involved as a researcher too. I feel my work is valued here where I am. There are opportunities – they are also not raining from the sky, but I am happy with the ones I’ve had in my career. I love learning and every relevant course I see, I enrol in. I feel a lot of this has turned out to be valuable to the projects at some point or another. I feel I am lagging behind in many new things happening in terms of image analysis and artificial intelligence. There are millions of things, and I constantly try to bring the most up-to-date knowledge to the platform.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Argentina?

I feel that through the courses and training I have taken, it’s been possible for me to meet people from the region. You also get to know what other people are doing. Most recently, another things that has made collaboration easier is that many pieces of equipment are Zeiss. We did it this way because the service packages/combo are easier and cheaper this way. So the Zeiss personnel have been very good at keeping all the members of core facilities in the region, in touch. We even share WhatsApp, even with personnel from Uruguay and Chile. When we have an issue or a doubt in terms of technical aspects of the microscopes, we communicate between us. Maybe you face a problem that someone else has already faced and already knows how to address. In fact one of those friends is Marcela Diaz from Uruguay, whom you have interviewed in the past for this Focal Plane series.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as an Argentinian researcher, working abroad?

I’ve had a chance to do training abroad but not to work for extended periods of time per se. When we bought the LSM880, with the package of the equipment, there was a chance to train with Zeiss in Jena. This was close in terms of dates, to some courses done by Global Bioimaging in 2016, taking place in Heidelberg, on data management and management of core facilities. I applied for a grant to go to both courses and was successful. This was a great experience. I got to see how different core facilities are managed, and this is always very enriching. I had a chance to go back in May last year, also to Heidelberg, for training in light sheet microscopy, under the project OpenSPIM. In November last year I went to Uruguay, to a course that the Pasteur Institute in Montevideo offered, on spectrophotometry, organized by Leonel. I will be going again next September to the LABI meeting. Perhaps in terms of language, I’d like to think my level in English is good enough for me to communicate. I think it’s more than enough. When I went to train in Germany, I proposed the project I wanted to do, and had a lot of independence to do what I wanted. Of course this independence can be a challenge, but it’s something I valued greatly. Also in Germany, my boss proposed that I learn how to do Brillouin microscopy, and at that moment, we decided to include a fluorescence channel – we had this project, and it was challenging for me because I had never worked with Brillouin microscopy. This was all super new to me, but I enjoyed it greatly. I enjoy intellectual challenges 🙂

Who are your scientific role models (both Argentinian and foreign)?

This question is very tricky. OK. Outside Argentina, I’m not sure I have any. While I was abroad, I had a chance to meet various people at EMBL Heidelberg and found the level very impressive. Each of them understands about all types of microscopy. It’s impressive. Here in Argentina, my role models are Hernan Grecco, Fernando Stefani, Alfredo Cáceres, and Lia Pietrasanta, who have been doing microscopy here since always, and they know the entire history of microscopy. They have seen the evolution of microscopy since its birth, and have been accompanying all the progress ever since, including the big boom that had happened in the last 10 years.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Argentina, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I think it’s improving in general, in Argentina, which I feel is great. But my field at least has always been led by men. It’s curious though – women have always been involved, but rarely ever at in power or leading positions. This is slowly changing, which I think is superb. The Institute I am in, has two branches: the Centro Tecnológico de Rosario, and the University. The directors of each are one man and one woman. This is great. Nonetheless, there are more women in the field, than men. But in the positions of power, this proportion is lost. But there are a few women reaching high positions – like Lia Pietrasanta, or Valeria Levi. These are decision-making positions, which is vital for change and progress in the sense of gender balance in the future.

What is your favorite type of microscopy and why?

Overall, it’s optical microscopy. I still think electron microscopy is spectacular, but since I joined the field of Cell Biology, I feel optical microscopy has a wider range of applications and contributions to cell biology. Going to specifics, I love confocal microscopy. I think you can have a look at a huge plethora of samples – one can look at tobacco plants, Arabidopsis, zebrafish, fixed tissues, live cells, live animals, sperm, etc – it’s endless. Equally, you can do a lot of things with confocal microscopes – they’re super versatile. You can look at fixed samples, live samples, fast imaging, detailed imaging, etc. I don’t know any other microscope that has the same, or higher, scope than the one a confocal microscope has. When we bought the LSM880, we had in mind that it could serve as many groups as possible, and one that we could configure to really help everyone in our institute. I also love dark field microscopy – looking at a neuron is unbelievable considering that you are looking at it with white light. But it does not have the versatility that a confocal microscope has.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

Uummm, I’m not sure, once we were starting to test the reflection mode of the microscope that works with non-fluorescent solid objects, we didn’t know what to test for and I had a coin in my pocket. It was a one peso coin, and I acquired an image which is unbelievable. In general I find looking at something new that no one has ever looked at before, is something magical. I vividly remember the first time I saw microtubules and it was fascinating. Also, helping a user know their models better is great. I like that with my experience I can help users notice new things that perhaps they were not expecting. Having looked at so many samples, it becomes easier to recognize unexpected phenotypes, which perhaps a less experienced user doesn’t immediately see or expect. You also get to find aberrations more easily, or alterations (like cells with mycoplasma). You can help the user by telling them that perhaps their cells are contaminated. I think this serves my purpose in terms of technical assistance too.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Argentinian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

My main suggestion is never stop learning and try staying up to date. Especially in an area like microscopy which doesn’t stop progressing. I see that some people find their niche in a specific technique or a specific protocol (which I think this is good and can be fruitful), but then are afraid of trying new things. Never close your mind to new and perhaps more efficient protocols or tools. Don’t close your eyes to the possibility of doing things in a different way. From one day to another, new techniques come up.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Argentina, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

Argentina has seen a ‘boom’ in microscopy in the last decade. I think over the last few years, Argentina has invested a lot in infrastructure, which will become fruitful in the years to come if we use it well. I hope the field of microscopy will continue to grow in Argentina. Buenos Aires and Cordoba have been hotspots for microscopy, but perhaps other regions in Argentina are more reluctant to incorporate microscopy into research, and to invest in this type of technology. Hopefully this will change in the future. Actually soon we will get new equipment in Rosario, to get super-resolution. We are getting an AiryScan and an Elyra, where we’ll be able to do PALM and STORM. We’ll be able to incorporate non-stochastic super-resolution to the research in our institutes. I hope these two microscopes will push science further in Rosario.

Beyond equipment, in terms of research and development, there are people in Argentina doing fantastic work, and I hope this doesn’t stop. Fernando Stefani and Hernan Grecco have done incredible things. The lack of funding (perhaps general in Latin America) sometimes allows you to become resourceful, and this sometimes allows you to find novel ways of doing things and even create new technologies and methods. I think we should capitalize more on this.

Finally, the initiative that Uruguay has begun, on LABI and promoting networks will be vital to foster collaborations in the region, to share knowledge, equipment, protocols – everything. I am really looking forward to the upcoming LABI conference. Collaborations are like a snowball, and I think this will be very positive for our region.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Argentina a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

In terms of science, we have a capacity for improvisation for problem solving, which is incredible. We don’t get stuck with problems, we have to be resourceful. We adapt easily to situations, which I think is a good trait. I think, though, that it’s important to be well organized – if you rely too much on it, you end up living through improvisation. I feel that perhaps in other places that rely a lot on structure and organization, spontaneous problems (which is usually how problems are) can cause a lot of stress. This is not often our case – this is not only true for science. And then, I think that we Argentinians are very friendly! The spontaneity we have as scientists comes probably from our spontaneity on a personal level too.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)