An interview with Andrés Kamaid

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 3 October 2022

MiniBio: Dr. Andres Kamaid is an Associate Researcher at the Advanced Bioimaging Unit of the Institut Pasteur Montevideo (IPMon). He obtained his Bachelor´s and Master´s degrees from the Universidad de la República and PEDECIBA, doing his early research in neuronal death and neuron-glia interactions at the Instituto Clemente Estable, under the supervision of Dr. Luis Barbeito. He then got his PhD from the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain, investigating inner ear sensory development with Prof. Fernando Giráldez. He has worked as Assistant Professor of Histology and Embryology at the Faculty of Medicine the Universidad de la República in Urguay and Associate Researcher at the Instituto de Fisiología Celular of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico. During his career, he has worked as visiting scholar in several institutions including the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, University of California Davis, San Diego and Irvine. Since returning to Uruguay, he has been involved in community building activities, such as the gender equity commission of the IPMon, as well as initiatives for developing research capacities in microscopy and bioimaging. He was the PI of the “UruMex Microscopy” project, an international cooperation project that promoted science and microscopy in different social sectors, and lead to the creation of Latin America Bioimaging (LABI). He is member of LABI executive committee and participates representing it in the management board of Global Bioimaging.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

As a child I was always very curious, and wondered about the “why’s” and “how’s” of nature facts. For some time I was mainly fascinated with Physics and Astronomy and spent hours observing the sky at night. What inspired me to do science as a career was that desire to understand nature. But there was also a strong, and naïve, idea that through science I would be able to find solutions to problems affecting humanity. Furthermore, I must say that I could have followed other paths (like arts, medicine or social sciences), if it wasn’t for a friend – Hernán, also known as “Peteque” – who had a tremendous impact on me. He was probably the youngest scientist I’ve ever known. From a very early age (7-8) he had decided to study Biology as a career, and it was obvious that he understood it in a completely different way than all the rest of us. You could see it in the way he interacted with nature – with plants, animals and everything around him. We were very close friends, and were together at school for many years, so at the time of choosing a University career, he was a very strong influence for me going into the Faculty of Sciences.

You have a career-long involvement in neuroscience and microscopy. What led you to choose this specific career path?

I started university enrolled in two degrees: Physics and Biology. I was passionate about many things – several topics. But to be honest, when I thought about the degree in Biology, my initial expectation was to specialize in more “macro” disciplines, like Ecology, Evolutionary Biology or Marine Biology. Some serendipity then played a role. In the first year’s “Introduction to Biology”, which was the only course specific to Biology (the others were Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry), we had to choose among different biological-disciplines. When I went to register, there were no more vacancies for Evolution or related topics, so I chose another topic that ended up defining my actual career. At this time, I met Dr. Ricardo Ehrlich and Cora Chalar, that really made me love Developmental Biology. Also, I met my first mentor: Dr. Luis Barbeito. One day, while painting the walls of the laboratory-teaching rooms at the old Faculty of Sciences, Luis offered me to visit the Cell and Molecular Neurobiology laboratory that he directed at the Instituto Clemente Estable. I still remember that conversation that triggered my somehow hidden interest in the brain and understanding of the mind: a few months later I joined the lab as “asistente honorario” (ad honorem assistant), and I convinced two good friends to join us. It was an amazing time of learning and having fun, and it was there that I really started to specialize in Neurosciences. Luis’s work had focused on classical neurochemistry but at that time he was just coming back from the prestigious College de France, beginning to move into more molecular and cell biology – an area that was just starting in the country, so it was challenging and exciting at the same time. Together with Alvaro Estevez, a PhD student at that time, they introduced me into the world of neurobiology and the cell biology of neurons and glia. Joining this group allowed me to know a network of people who were doing really fascinating science, in Uruguay and abroad. As a young second-year´ University student, all that experience was incredibly nourishing and intellectually-super-stimulating.

It was during those first years that I found out microscopy was really my calling, even more than biochemistry or molecular biology, areas that were very attractive and highly “in the spotlight”. I remember that at the time we didn’t have digital cameras: we had to take pictures with an external analogic B&W camera, go to the photographic lab and develop the picture ourselves, to then sit down and manually count neuron numbers or measure neurite length. I felt I was doing exactly the same I used to do for my hobby of artistic photography, that I always enjoyed a lot. Since then, I realized the power and beauty of studying the brain (and cell biology in general) via imaging. Naturally, studying neuroscience the work of Ramon y Cajal was very influential for me: the incredible drawings he was able do and the amazing discoveries he did with them, and just (just?) by observing through the microscope! Even today, with all the technology we have, his discoveries stand strong and represent pillars for neuroscience. I also remember that around the time I started my BSc, drawing was a very important skill to have for any biologist. Many scientists in Uruguay used to draw their microscopic observations, and so did I!! Sadly, with time I stopped and now I barely do it… big mistake, I think. Maybe, all this is why I found microscopy-imaging more fascinating than molecular biology. I’ve always loved the possibility of linking cellular form, function, in vivo context… and other possibilities that microscopy visualization allows. Having said all this, I don’t consider myself a microscopist per se. Maybe more accurate would be to say that I use microscopy as the main tool for my research, in an extensive and quantitative way. In other words, I want to understand the behavior of cells and tissues in vivo, but I don’t build myself the microscopes to do it. In spite of this, I love working closely with microscope-technology developers, and I think it is fundamental for the advancement of microscopy-imaging. To be honest, I wish someone had triggered the interest in hardware-technology development when I was younger… a beautiful place where Biology and Physics meet.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Uruguay, from your education years?

First, I think we are used to challenges – to solving problems with the resources we have at our disposal. For my scientific career, this was helpful. A funny example: long time ago inter-nucleosomal DNA fragmentation was the hallmark of apotosis and the reviewers of a paper would not accept it without an agarose gel demonstrating it. Molecular biology tools were scarce in the country still, and we didn’t have a proper (commercially manufactured) tray to do gel electrophoresis and we were in a rush. I remember doing my own electrophoresis bucket with a box of Ferrero Rocher chocolates, that not only allowed us to demonstrate that neurons were dying by apoptosis, but maybe more important, to incorporate that technique in the lab for the future. While this is a very “simple” anecdote, I mention it as an illustrative example that can be applied to bigger things. In Uruguay, often we cannot wait to have the money to buy super expensive equipment, or reagents/techniques, so we must be creative with the existing capacities. Another advantage I see in Uruguay is, paradoxically, its size. The scientific community is small, and even though this has tremendous disadvantages, it also implies that distances between scientists are reduced. In my case for example, even as a young scientist I was able to interact quite closely with well-renowned scientists in the country and from various disciplines!. That is… if you study biology, most professors in the career get to know you quite well (and viceversa)! I remember, for instance, having a course with only 5 classmates and Dr. Elio Garcia-Aust, a remarkable Uruguayan neuroscientist…it was incredible! I do believe this level of interaction was very beneficial for my career. I’ve seen that in bigger institutions and bigger countries, this close interaction is way more difficult (or not even possible). In our case, I think having this close contact with professors/referents makes your early career a more personal and motivating experience.

Can you tell us a bit about your path, and how did this shape you as a microscopist?

As I mentioned, I was very young when I joined the Instituto Clemente Estable, which is an institute that has a strong tradition in microscopy, specifically, electron microscopy dedicated towards neuroscience. Our work with Dr. Luis Barbeito was focused on oxidative stress and neuronal death and we began collaborating with several strong groups in the field of free radical biology, both in the USA and in Uruguay. For instance, the group of Dr. Rafael Radi from the Faculty of Medicine, and Dr. Joseph (Joe) Beckman from the University of Alabama, Birmingham, among others. At some point the national financing for the projects were very scarce, and immediately after graduating I was given the opportunity to continue my work in the lab of Dr. Beckman in Alabama, where I spent two years working on the mechanisms of neuronal death during lateral sclerosis. The UAB center for Free Radical Biology was a special place to be at that time, top class in a field that was in the “spotlight”. For example, the Nobel prize was awarded for nitric oxide physiology studies in those years and being there I got to know a few of those fantastic scientists personally ! Meanwhile, It was there that I saw a laser scanning confocal microscope for the first time, and I learnt that there were “imaging core-facilities” with specialized experts running them. At some point, Dr. Beckman’s lab in Alabama split, with some moving to Oregon and I decided to came back to Uruguay to continue working with Dr. Luis Barbeito and Dr. Rafael Radi. I finished a MSc. in Neuroscience and started working as Assistant Professor of Histology and Embryology at the Faculty of Medicine. During this period, I learnt a lot about cell biology, histology, immunohistochemistry and fluorescence microscopy. I also had the chance to do long enriching research periods at UCDavis in USA, with Dr. Jason Eiserich, but It was a very difficult economic period for Uruguay and I decided to move to Barcelona. I spent there about 4 years, working with Dr. Fernando Giráldez and obtaining a PhD at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Those years really changed a lot my relation with microscopy and imaging. My work became more based on it and I also got the extreme luck of having Fernando not only as a mentor but as a close companion in the lab, which increased a lot my knowledge and enjoyment of working at the microscope. Besides, the Parc de Reçerca Biomedica of Barcelona, where we were located, was an amazing environment for learning state-of-the-art imaging. I was exposed constantly to many world class imaging scientists, like James Sharpe or Timo Zimmermann, just to mention a couple. Despite my previous experiences and interest, those years in Barcelona were really a turning point.

After the PhD I moved to Mexico, and joined the group of Fernando López-Casillas at the Institute of Cellular Physiology, UNAM, as an Assistant Researcher. I continued working on embryonic development using zebrafish as a model, with a big emphasis in live imaging. It was during this time in Mexico that I got to know the Laboratory for Advanced Microscopy in Cuernavaca, and his director Chris Wood, who would turn later into an important partner and collaborator. A few years later, with Chris we started the UruMex Microscopy project that has been extremely rewarding for our imaging community. In 2016, after almost 15 years of living abroad, I returned to live in Uruguay, working at the Institut Pasteur de Montevideo. However, it was one year before, during a visit to give at the IPMon, that I met another scientist that would help “shaping” my relation with microscopy. His name is Leonel Malacrida, and he was about to finish his PhD when I first met him. I remember that after my seminar we stayed talking for a while about microscopy-related issues that could be applied to my work. A couple of days later we were already doing experiments in the Leica SP5. The results were very interesting and promising, but soon after that I left to Mexico and he went to the LFD in California for his post-doctoral training. In spite of this, we managed to keep alive the collaboration, that grew into a partnership that has greatly transformed many aspects of my relation with microscopy, shaping dreams and building realities. For a few years we worked at distance in several projects, and I visited the LFD a few times. It was there that I had the great pleasure to personally meet Enrico Gratton, who has also had a tremendous influence on us in many ways. Apart from being one of the most amazing scientists I’ve known, Enrico has been extremely generous as a mentor and human being, always very supportive with our work.

Can you tell us a bit about Global BioImaging, and the CZI project you lead?

Global Bioimaging (GBI) is a fantastic network of people from all around the globe, with varied backgrounds and expertise, including imaging facility operators, imaging technical staff, scientists, managers and science policy officers. GBI’s mission is “to cooperate internationally and propose solutions to the challenges faced by the imaging community globally”. Importantly, in GBI we work together for building imaging capacities along the world, based on the idea of learning from each other’s strengths and capabilities. Besides, another important role that GBI plays, is to communicate to society and policy makers about the importance that imaging technologies and research infrastructures have in the advancement of life sciences. I would like to say that GBI has played an important role in the formation of Latin America Bioimaging. We were invited to participate in the management board meetings from LABI´s very beginning, what was very encouraging for us. It helped a lot not only to see that we share a lot of common challenges with seemingly different regions, but also that we can contribute to the global community. For me GBI is really an example that we can all learn from other’s experiences and that working together as a community is beneficial for all members.

Our CZI project is very much aligned with the ideas of GBI. It aims to help building community and capacities in our region, through the consolidation of Latin America Bioimaging. This is a network that intends to occupy a new space that has emerged with modern imaging ecosystems, working in synergy with already existing scientific societies. With this project, we were able to hire a full time person to help executing the network activities, which include the development of a web-based platform that will serve as a regional reference for imaging resources (training, equipment, etc), and also training programs to improve-promote access to imaging resources, and support imaging scientist careers.

Throughout your career, did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Uruguay?

Yes, for me this was crucial and it is one of the reasons I wanted to come back to Latin America after my PhD in Europe. When I worked with Dr. Luis Barbeito at the Instituto Clemente Estable, he had many collaborations and I immediately realized that it was of tremendous value. He always encouraged collaborative work with people from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, etc. In this way I met many latin American scientists and different realities in Latin America, and appreciated the big value of the science being done in the region. Besides, while I was a student I participated in several regional courses, that also allowed me to be in touch with the science being done in the region and appreciate its high quality and potential. As a young scientist this was very motivating. Unfortunately, when I went abroad I didn’t have much contact with people working in Latin America. Most of our collaborators were in Europe or the USA, so once I came back to Uruguay, I have had to re-build all connections and start new ones.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Uruguayan researcher, working abroad?

First, a funny one: I joined Dr. Beckman’s lab in the Center for Free Radical Biology of the UBA due to his connection with Uruguayan professors (R. Radi and L. Barbeito). In particular, R. Radi is a distinguished scientist who had previously worked with Beckman in Alabama and had built a fantastic career there. This paved the road to several young Uruguayan scientists to go to Alabama. I was one of them. But because of this previous stories of success, I felt there was an unspoken expectation for Uruguayan scientists to be very good. This turned into a challenge for me: to live up to this expectation. In a way it did represent some pressure, because I felt I was representing my country and had the responsibility of keeping this reputation and doors open for future scientists, as my predecessors did form me.

Beyond this, I think a challenge I felt as an Uruguayan working abroad, was to overcome a certain fear to ‘think big’. I feel sometimes there is a complex in Latin Americans, that our science is somehow ‘less than’ or ‘inferior to’ the rich countries. Actually, Dr. Radi was one of the first to give me this piece of advice: “you need to have the courage to overcome these complexes… always think big”.

Who are your scientific role models (both Uruguayan and foreign)?

During my career there have been many people who have been very influential. I’ve mentioned mentors and professors like Luis Barbeito, Rafael Radi, Joe Beckman, Fernando Giráldez, Enrico Gratton. Moreover, I should also say that I have learnt so much from, and admire, colleagues and friends of my own generation-age: Hugo Peluffo, Laura Quintana, Juan Carlos Vallelisboa, among others. But to be honest, I don’t think in any of them as role models in the sense that I haven’t replicated what they do, or have done… surely a pity !

What is your opinion on gender balance in Uruguay, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

This topic is extremely important. Gender equity is something we need to work hard to achieve… and there is still a long way to go. A simple fact of my career: while I have had the opportunity to work with many women as colleagues, I have never worked with women as supervisors-mentors, and that’s sad. In my humble opinion, in great part this reflects the so called the “glass-ceiling”, only one of the consequences of “gender-gap” in science. Thus, when I came back to Uruguay I decided to join the Gender Commission (GC) at the Institut Pasteur, trying to contribute to this topic, at least in my community. The GC was initially formed after an 8th of March meeting, voluntarily and spontaneously and only later on, due to the important job done by it, became an official part of the Institute’s organigram. That was already an improvement, that later on helped establishing a “Gender-quality-program” at the IPMon. This is a program by the government agency “Inmujeres”, which aims to reach gender equity in institutions. I must say that working in the GC has been one of the most rewarding activities I’ve had so far at the IPMon. Not only did I begin to recognize problems I was previously unaware of, but also to see my own unconscious biases.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

I love all types of microscopy, mainly applied to live imaging. If I have to choose, I would say light-sheet microscopy, because of the possibility it offers for studying cell functions and behavior in vivo. I believe light sheet technology has opened (and will continue to) a new door for developmental biology and a bunch of other fields of research. Another type of microscopy I love is “frugal microscopy”: open-source, based on low-cost, commonly available materials. I think this type of microscopy is essential for many things, including democratizing science and involving all the general community in the process.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

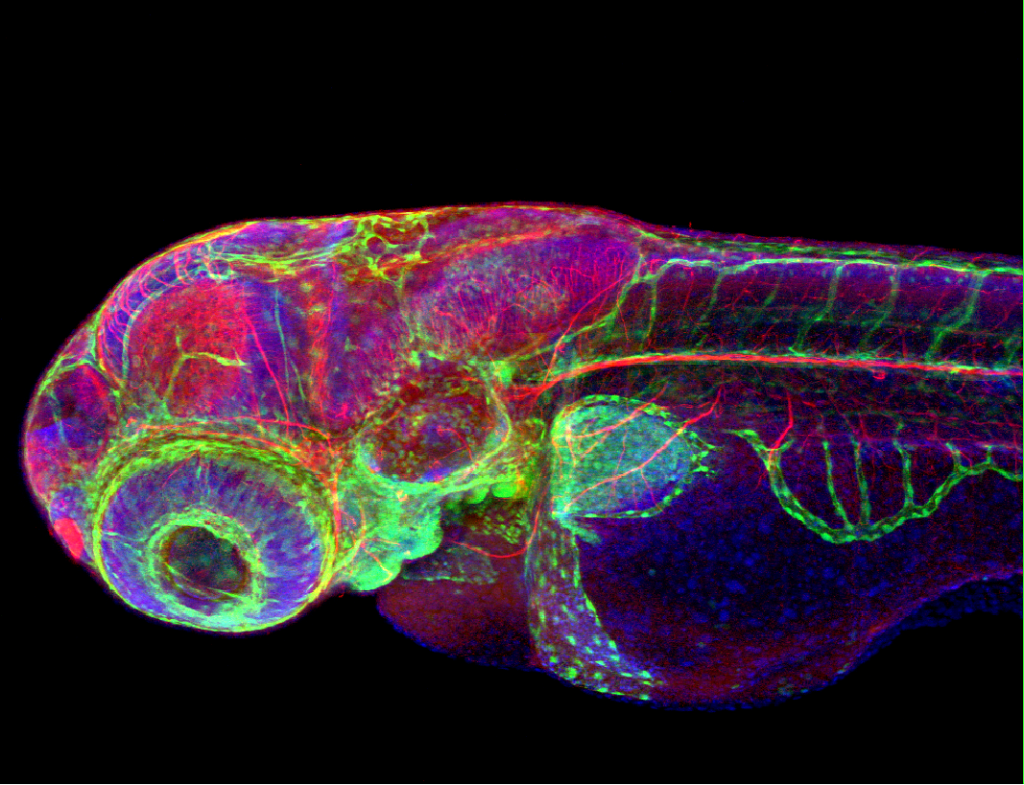

I’ve seen millions of extraordinary things. In fact, each time I sit at the microscope to look at an embryo I feel a lot of excitement. Every time ! I feel happy I still haven’t lost the capacity of wonder by just looking at the microscope, but I also bear in mind the words of Dr. Fernando Giraldez, paraphrasing Ramón y Cajal: “beware of being paralyzed by the aesthetic contemplation of nature’s beauty”. Nevertheless, If I have to choose one moment, it might be the first time I did an IFA of GFAP in astrocytes. It was something I had only seen in books… and I had prepared it myself!!! One more, I also remember the first look of certain zebrafish morphants under the fluorescent scope. We were downregulating a gene recently cloned by our group, so we were the first ones ever to observe what effect that could have. Macroscopic morphology of embryos was almost indistinguishable from control embryos, but then we used a transgenic GFP line for a specific type of neurons. When the fluorescence light was on… boom… very clear abnormal morphologies and neuronal distributions !! Discovering that unexpected phenotype was kind of an “eureka” moment… there is definitively something extraordinary that you feel when seeing something that no-one ever has!

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Uruguayan scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

I don’t like giving advice. But if I have to say something, my first piece of advice would be to learn how to collaborate in interdisciplinary groups. Microscopy is particularly rich in this sense, combining Biology, Physics, hardware design, computer science for data analysis and management, etc.. If you can handle interdisciplinary collaborations, you will make the most of it. Besides, imaging technologies evolve very quickly and you do need this capacity to interact with people specialized in those different disciplines. And this is not an easy thing to learn !! – I mean to effectively communicate in a fruitful-efficient way with scientists of other disciplines.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Uruguay, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

One of the problems we have in Latin America is the lack of continuity in scientific policies, or maybe the lack of strategy at all. For instance, in Uruguay, the sudden wave of media coverage of science during the COVID-19 pandemic was impressive. Politicians manifested publicly about the importance that the scientific community had for our country to handle such a public-health crisis. However, this was not reflected in any significant concrete policy that affects science afterwards. Thus, to me it is truly not clear where science is going over the next decade here in Uruguay. In spite of this adverse context, there are initiatives that give me hope and that I endorse, like investiga.uy: an organization of scientists that aims to contribute to the development of a solid and sustainable scientific system.

When it comes to microscopy, I see some changes. First, there are more people interested in developing capacities in the country and an interest in the local community to reorganize itself and prioritize the community above the individuals. I am a strong believer that we have to work as a community and this is the vision I will continue to work towards. Another thing I wish to contribute to change is the perceived value of the work we do: science currently is not equitable, and we are measured by standards that have little to do with the realities of our region. Open science initiatives must be thought and adapted to our community. Somehow we need to learn to make the distinction between real quality standards and current imposed metrics. Obviously it’s a very complex thing to change, but we must work on it. For example, I believe our own evaluation system is not well designed: it judge us on the basis of metrics that we cannot reach: we don’t have the money to publish in high profile journals ! – the dog gets exhausted chasing its own tail!

Beyond science, what do you think makes Uruguay a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

It’s a small country, but it has a lot of the characteristics of a big country: you can do great science in a way that allows close interactions with the scientific community. These human interactions are extremely valuable in every way. People are very accessible and friendly. Montevideo in specific, has a huge cultural wealth which you can access quite easily…

(1 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

(1 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)