An interview with Paola Scavone

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 4 October 2022

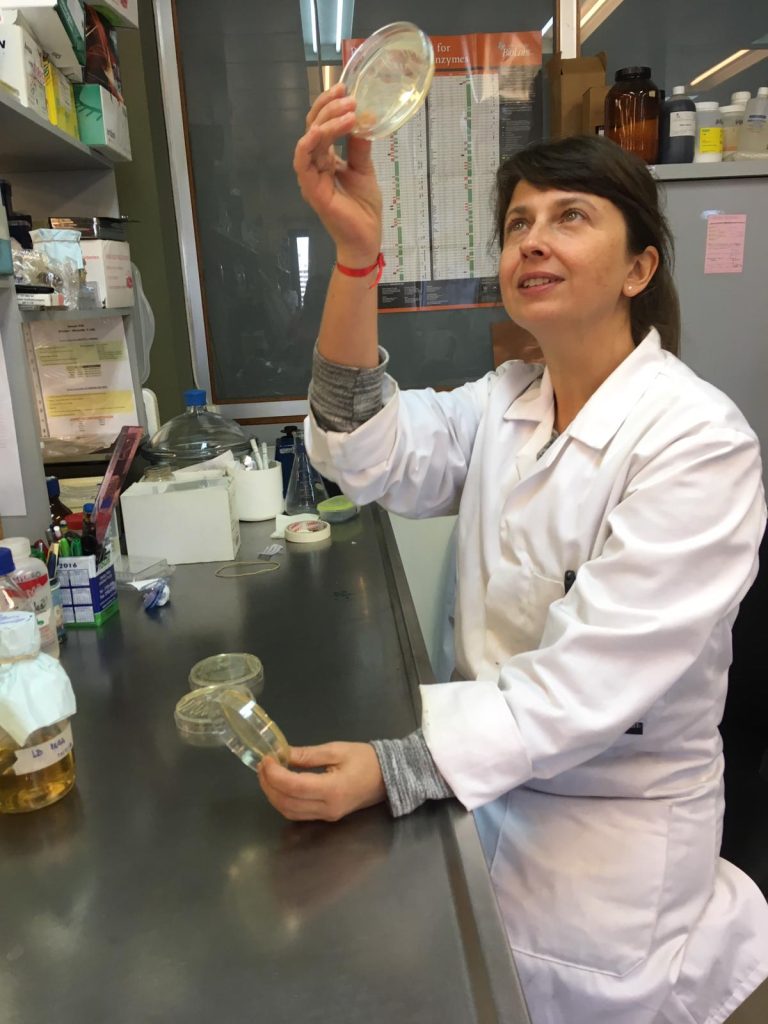

MiniBio: Dr. Paola Scavone is an Assistant Professor at the Instituto de Investigaciones Biologicas Clemente Estable (IIBCE) in Montevideo Uruguay, working on biofilms in urinary tract infections. She studied her early career (BSc and MSc) in Uruguay, and part of her PhD in Chile, in the lab of Dr. Stefen Hartel, where she first entered the world of microscopy. She then did two postdocs, one at the IIBCE in the Department of Microbiology, and one at the University of Brighton, UK, in the School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences. Parallel to her work as a researcher, Paola is also heavily involved in scientific outreach and scientific communication. She is part of a group of microbiologists that generates comics addressing various topics of microbiology as well as online games, video games and short films aimed at children and adolescents, which have been distributed across Uruguay.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

This question is a classic! Actually I didn’t know whether I wanted to become a scientist. Perhaps this hesitation is no different to that of many other scientists. I knew I liked the Biomedical Sciences, but I pondered whether to study Medicine, Chemistry, Biology, etc. Then a friend of mine invited me to the Faculty of Sciences and told me about the type of work done there, and here’s where I thought ‘ hmm, maybe this is my path’. But when I was younger, I had certain curiosity about sciences, and my parents gave me as a present some games, like ‘El quimico precoz’ or ‘Cheminova’. Let me show you! *shows boxes of games*. This is a game which allows you to test reagents. The typical cartoon-like concept of what a scientist does: in a lab you basically mix reagents, and things explode! At the time, I feel my generation was one which could enjoy the outdoors – we used to play outside, with bugs, plants, etc, doing experiments. I used to spend all 3 months of summer holidays in my grandparents’ ‘chacra’ (i.e. small ranch), and the only thing to play with, was the nature around us. So we had to improvise and observe whichever small bug we could catch. This left a mark in my childhood, and later I was able to join the dots, once I decided to pursue a career. Nowadays I wake up and do this, because I truly truly love it.

It seems your passion for bugs continued, albeit a different type of bug: you have a career-long involvement in microbiology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose these paths?

When I had to choose a career, I chose Biochemistry: Right in the junction of Biology and Chemistry ☺ I actually would have loved to study Medicine too, but as you know the degree of Medicine is very long: at the time I thought about this from the job-prospect point of view – that I would have to study for many many years before I could get a job, and this was a bit of a deterrent. I decided to do a shorter degree (Biochemistry), and could start working much sooner. But if we count the total number of years I spent studying, say, those for the BSc, the MSc, the PhD, and two postdocs, this adds up to about 2 medical degrees in terms of time. But anyway, time was a factor that helped me choose. The other advantage I saw in science, is that it allows you to relate to many different professionals. In the area where now I am as an established researcher – Microbiology- I work with many medical doctors. At the end of the day, for me it’s important that the knowledge we are generating at the bench reached the general public! I find it essential that the science I do is useful to and used by the general population.

My entry to Microbiology was a bit of serendipity: it was a subject within the degree of Biochemistry, and I found it fascinating from the first moment. These little, simple ‘bugs’ are so powerful that they can kill a big mammal like humans. I realized there were millions of things to investigate in bacteria, that they play a vital role in our daily life and perhaps we don’t give them the importance they deserve. We don’t think about them as part of our own organism for instance. I was lucky to join a Microbiology lab where I could do my final project for my degree. I had to do two projects: one that is practical and the other, theoretical. After I did my BSc project there, at the lab they invited me to stay on to work on a project – I decided to do my MSc degree there too. Then I did a few internships abroad which allowed me to see other places and meet new people. After the MSc I went directly into my PhD – at the beginning I didn’t have a scholarship so it became very complicated. I met Steffen Hartel (from Chile) around this time, and he invited me to work in his lab for one year. I decided to go, but I asked him if it would be ok if the work I would do with him could be part of my PhD. He agreed and I went to Chile. That was the first time I joined the expertise on Microscopy with my interest in Microbiology. It was interesting because in his lab they do a lot of image analysis, neurosciences, development…and I came along with my bacteria. Steffen opened the doors of his lab, and put all his resources (microscopes included) at my disposal. After all, for microbiologists, microscopy is THE tool for research – we use it on a daily basis! In this time, I started finding my own niche for research, namely biofilms and urinary infections. I am lucky that to this day I am still collaborating with Steffen. He was the one who awakened my curiosity and interest in microscopy. Microscopy is a discipline which involves a lot of Physics, and I used to hate Physics! During high school I used to loathe it, but when I worked with Microscopy, everything I had not understood during high school became totally clear as a microscopist – it was applied and I was able to understand what was going on. It was there I realized that the assimilation of knowledge and love for a discipline all depends on how well people teach, and how efficiently they can convey main messages to the students. Then I did my postdoc: one in the same department where I am now in Montevideo, and then I did another postdoc in the UK, at the University of Brighton, in the south of England. This experience in the Global North showed me that we do have a different pace of work, and that it’s easier to do science over there. I think Uruguay has very good scientists, but we simply don’t have access to all the resources. We do great things with the few resources we have. If we invested in science and infrastructure, we wouldn’t ‘need’ to go abroad, other than for the experience of seeing new cultures. But as it is currently use, it’s difficult sometimes even to get Falcon tubes! Anyway, during both of my postdocs I continued on the line of Microbiology. My first postdoc focused on basic science regarding biofilms, and the development of models for the study of biofilms. In my second postdoc, I switched a little bit, towards applied science. Biofilms that are related to urinary infections are also highly linked to nosocomial infections, particularly associated with catheters. Urinary catheters are a tool that is very highly used in a medical context, and they’re also amongst the ones most easily contaminated. So I went to the UK to learn about models of biofilms within catheters, as well as doing a lot of microscopy. In the University of Brighton they had a very large amount of microscopes. You could use anything you wanted: a ESEM (environmental scanning electron microscopy), a confocal, anything you wanted. But in my lab, no one knew how to use the confocal for example. For this reason, I was able to collaborate with many of my colleagues to do the imaging side of many projects and/or do teaching with respect to microscopy. Now I have my own lab, focusing on microbial biofilms, which is within the Department of Microbiology. I think this topic now has huge relevance especially given the rising antibiotic resistance among bacteria, and the relevance of nosocomial infections. Once biofilms form, it is very difficult to get rid of them.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Uruguay, from your education years?

I think that education in Uruguay is really good. It shows us the big picture and is very diverse. In the degree of Biochemistry, for instance, they teach a lot of skills, and this ends up giving us a lot of tools, which in turn gives us a lot more flexibility in our careers. We can shift from one area to another, and/or do interdisciplinary research. It makes it easy to address and solve problems that are interdisciplinary in nature. And the issue of having not so many resources, also in its own way makes us more resourceful: you have to learn how to do many things from scratch because we can’t afford to buy kits, or ready-made reagents; you have to learn how to use the autoclaves on your own, how to wash the glassware, how to do every step of the experiments, etc. Having to know how to do each step is an important part of the scientific career in my opinion, and it gives you a high degree of freedom: if the lab technician is absent, you know how to prepare everything you need. Although sometimes I would prefer to have many technicians who can make it easier for my lab to do science, I still think it’s very valuable to be able to solve problems on one’s own when they arise. But this is also a philosophy of leadership. I try to encourage people in my group to learn the basics of all the techniques we use in the lab: understand the basics of the methods, and use them. In the near future, you don’t know how necessary this might be for you or others. Also, you can’t predict the future: imagine that one day you can’t go to the lab for some reason and someone needs to take over your big experiment. The fact that we share knowledge and everyone in the lab knows how to do the basic experiments of the lab means that someone will be able to take over. We will be able to help each other more easily. And this goes beyond techniques too: I don’t think we should be territorial when it comes to knowledge. Knowledge should be shared! There’s nothing to be gained from an attitude of ‘I won’t tell you the important details of the experimental part of this experiment’. And at least in my career, this was an attitude displayed even by leaders of big groups: ‘this is MY topic and MY area’ – and would keep things secret or deter everyone else from entering a specific field. My philosophy with my group is that the more we share knowledge, the easier science will be and the more we will be able to advance in terms of scientific discoveries. We all have a specific expertise (or more than one), and it’s great that we can collaborate with people who have expertise in other things. It’s not good to accumulate knowledge without sharing it, and I think we should do a lot more in terms of science communication, especially towards society – there’s a huge gap in that aspect. We’re trying to do something on this front too, but we have 24 hours per day to do everything we want and need to do. However, we try – I think as scientists we should encourage scientific outreach: people communicating, sharing and making knowledge exchange much easier.

You are in fact heavily involved in science communication and comics! Can you tell us a bit more about this?

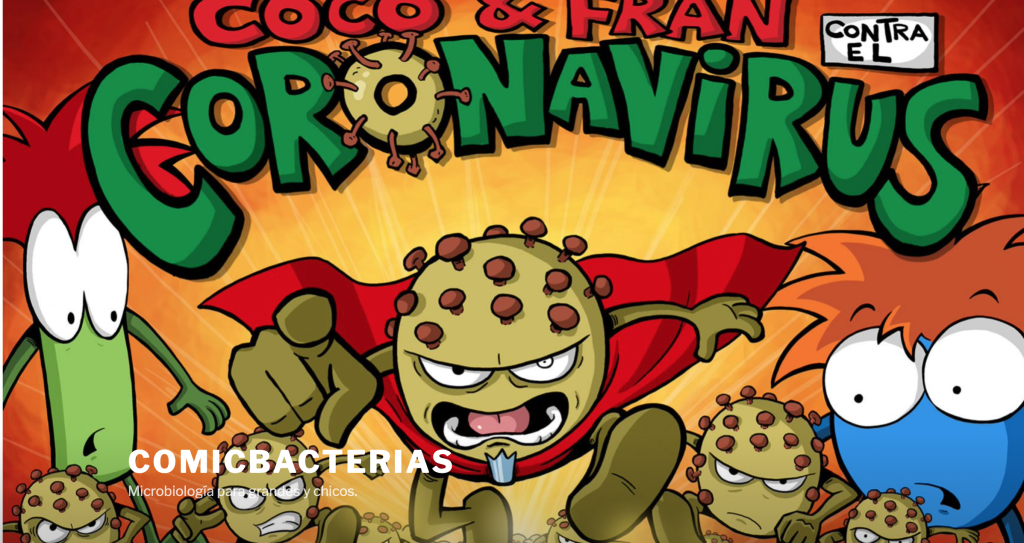

This goes hand-in-hand with my daily work of trying to share knowledge. I worked many years at a school, in the area of recreation so I had all this knowledge and experience once I became a scientist. I love working with children and adolescents. It’s fascinating and they challenge you often. Besides of it being a valuable experience, this was the job that allowed me to become a scientist – to pay for my degree, my books and everything I needed to study. Anyway, this is when I identified the gap that exists in terms of bridging scientific knowledge and scientific discoveries with the general population. Prior to the pandemic, we opened the doors of our lab, so that children and adolescents could come, and we do experiments together and tell them about our research and about the scientific process. It was here we realized that there’s little in terms of material on microbiology aimed at children and adolescents here in Uruguay. They all arrived thinking that all bacteria are ‘bad’, that we should eliminate 99.99% of microorganisms on Earth, and there’s nothing further from the truth! So we realized we needed to do something about this. The first thought that came to our mind was to write a book, but a book is perhaps one of the last thing that children want. So me and other microbiologists in the Institute started a project on scientific communication. As Uruguay is a very small country, we learned about ‘a friend of a friend’ who does comics (https://www.comicbacterias.com). We read some of their comics (on other topics) and found them great! So we told them we wanted to do comics on microorganisms, and it was very well received! A goal we set for ourselves beyond scientific communication was that the information in the comic would be very rigorous. We had to study a lot, because of course each bacteria is a world of its own. We have to choose the most relevant information – the heart of the topic- and decide how best to transmit that knowledge. During the pandemic, we decided we had to do something. There was a call around that time in which we did something we called a ‘Quarantine survival kit’ (https://www.comicbacterias.com/kit-cuarentena/), which included a comic, a video game, and 500 other things ☺ we worked for a full month, 8 hours a day on this. I had never designed an online game, and for the first time I did this. We started doing things that we didn’t think we could. I love that in the group we’re very versatile – but we have our ups and downs when it comes to the project. But at the end of the day we’re very happy and very pleased when the feedback we receive from the children is positive. And it seems this project is having a great impact at schools too. Before the pandemic we had done some outreach at schools with the comic, especially at schools far from Uruguay’s capital, Montevideo. This was interrupted during the pandemic and only now we’re starting to re-take it. Then we released a comic on vaccines – we had been working on it for 2 years – it’s a very delicate topic, especially with so many anti-vaccine opinions and movements. So we incorporated medical doctors to the group of scientists, to have the latest information from the clinical point of view. So we released the comic two years ago in December, just around the time when the COVID vaccine was announced, and several people told us “the timing is great!” but the truth is we had been working non-stop on that for 2 years! We did some short films with animations too – we’re still waiting for Pixar to reach out ☺ maybe they do! Anyway, our latest comic release was just sent to us – I’m excited it’s now going to be published. I must say, for the production of the comic, the video games, the short film, the animations, we don’t do everything ourselves – we collaborate with experienced teams! The online game, we did on our own – nowadays there’s a lot of information on the Internet – there are templates already available which you can fill in for your online game, and you can test it until it works and then release it. It’s much easier that it would have been many years ago to create something like this. Altogether, we first select the content and then meet with the designers and illustrators, and then we go back and forth with them to decide on what the final product looks like. It takes quite some time to make a comic- it’s not trivial! In terms of distribution, we had economical support from the National Agency of Research and Innovation (ANII) to cover the printouts, which allowed us to send at least one comic to each of the public schools in the country. We want all information to be freely available on the web: so if you want a comic, you can enter our website and download it as a pdf. If you want a printed version, then it has a small fee because paper and printing are expensive.

And then in Uruguay we have the ‘Plan Ceibal – one initiative aiming at one computer per child, and promoting and facilitating access to knowledge and information, and this includes a virtual library with plenty of resources. Our comic is included in this library of the Ceibalita – this is how most access is given. At present, however, we still don’t have a way of evaluating the impact of our comics on the children. The thing is for such evaluation, we would need to do an assessment prior to and after the release of the comics to see if the comic is really helping transmit knowledge. For us it’s impossible to do this at the moment. We have the feedback that the teachers have provided, but not a formal and systematic evaluation.

You should feel free to follow us on social networks, and access our webpage www.comicbacterias.com! The characters in our comics are much more famous than we as scientists are – they have a life of their own. When we go to congresses, we often present the latest comic, and it’s well received. I’ve given talks at congresses, and the attendance is great! And the participation is great too: we have scientists making scientific questions regarding the comic. We have won awards for best talk, for a presentation on the comic. I feel I have more success with the comic than with my work as a scientist. We were awarded another 3 prizes for this initiative. One was the Premio Morosoli, which recognizes contributions to culture in Uruguay, and then every year, a prize called Premio WEST that is awarded to comics, and we won this prize twice ☺

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day activities as a group leader?

It depends whether it’s summer or winter! I tend to arrive early to the lab because I like to be alone for at least 30-40 minutes to put my thoughts in order and organize my activities for the day. Luckily, because my students are much younger than I, they tend to arrive a bit later so I have this time. And then the activities vary on a day to day basis: sometimes I’m able to do experiments in the lab, other times the whole day is used in helping a student rehearse for a PhD defense, etc. I think as a scientist not two days are the same. Then I also dedicate some time to the comic, which is our treasure here. And then something linked to the comic is that we help other scientists communicate the results of their work: we do mini-comics on other topics. During the day I need to find time to read about a totally different topic to those of my own expertise and think how best to convey the messages. And then depending on whether it’s summer or winter, I like to do beach sports. I do stand-up paddle ☺ I’m addicted to this sport, and luckily Montevideo has great beaches to practice.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Uruguay?

Luckily during my MSc and PhD I did many courses and internships abroad, especially in the neighboring countries: Brazil, Argentina, and Chile – I was in Belo Horizonte in Brazil for 3 months. Then in Argentina I was in La Plata, and in Chile I went to Steffen Hartel’s lab. I think something we have in Latin America is a different level of progression and development when it comes to scientific careers. For instance, Peru and Paraguay until recently, did not have per se a scientific system. In more recent years all countries have begun to invest more in science. The more they do this, the more they promote scientific exchanges. For instance I recently had a student from Peru who came to my lab to learn about biofilms. Also, moving within Latin America is cheaper than traveling elsewhere in the world. So for us and for the students sometimes it’s easier to travel to neighbouring countries. To go to Europe or the USA you would need fellowships which offer a lot more money. I still feel we could interact more in Latin American countries- we share a language in most countries, which makes our interactions much easier! I think we should promote this better. I think we should see the European model of ERASMUS as an example – it allows exchanges between countries, and a program like that would exponentialize collaborations in our region. We’re a bit restricted with the economic issues though, but there’s a program which I always encourage my students to apply to: it’s UNUBIOLAC (https://biolac.unu.edu/en/education/fellowships#application-procedure), a program that gives funding for internships within countries of Latin America. With this program I’ve received students from Chile, Cuba, Peru, etc. It’s an interesting program because it pays for travel, insurance, money for the host lab, and covers the wages that can be used to cover the accommodation and living expenses. There’s not so many programs like this one, and the ones that exist are not widely known, so we still have to do more to communicate and share these opportunities. All the students from elsewhere in Latin America who have joined my lab to do internships have been awarded the UNUBIOLAC fellowship, so it’s clearly accessible, and there are resources.

When you worked abroad, did you face any challenges as an Uruguayan scientist?

I think that the most relevant challenge is to be far away from family and friends. For the people that stay here is like woow how fantastic you are traveling! But they don´t think that you are alone and that you have to basically start from the beginning again. You have to find a place to live, to know your new neighborhood, and sometimes the language is also a big issue. It is a fantastic experience. I strongly encourage students to stay abroad but it is hard. Then you have challenges as scientists of course, and I think that with our skills and education we are ready to face it.

Who are your scientific role models (both Uruguay and foreign)?

One scientist who really had an impact on my career, and whose lab I was actually in for a while is Pascale Cossart in France– she is a microbiologist, and she developed a new discipline within microbiology: cellular microbiology, which studies how microorganisms are models of cell biology, and how the prokaryote and eukaryote cells relate to each other. When I worked in her lab, I noticed she was really approachable, and she would dedicate enough time to every single person in her lab, to know what the new advances were and whether they needed help with anything. She was working with Listeria monocytogenes, and she did huge contributions to the field. She’s one of the most important bacteriologists of our time. And then Stefen Hartel in Chile who was the one who introduced me to the field of microscopy. Steffen believed in something that he had no clue about! He trusted me fully and supported me all along. I think this is super important in our career as scientists: someone trusting you and your capacities. He used to ask lots of questions – very interesting ones. But his positivity and trust was something huge in my career. Perhaps without it I wouldn’t have continued. And the nice thing is that he went from being great PhD advisor, to now being my colleague and collaborator. Now our students work together! And just like he gave me opportunities, we now together give opportunities to the younger generation.

In the field of science communication, I follow the work of many people who do lots of interesting things but I don’t see them as role models per se. I try not to copy anything: we have our own style and I want to keep this essence as something unique. I try not to pay a lot of attention to the type of communication, just to the messages.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Uruguay, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

This is a huge topic. It keeps me preoccupied and occupied! I think there a significant disbalance in terms of gender. If one looks at the numbers, there’s a high percentage of women doing science, but they don’t reach positions of power. The highest positions (and highest salaries) are mostly occupied by men. There’s a clear glass ceiling. The scientific career is very tough, and women do not face the same conditions as men. And then there’s definitely gender-based aggressions in the labs: sometimes it’s even with “small” things: eg. “[X woman in lab] is very tidy”. Or “Please help me wash this glassware because you know how to wash it very well”. Come on! But as a lab leader I pay a lot of attention not only to not fall on gender biases, but also to notice when other people do and address it. To prevent that micro-aggressions and/or aggressions happen at all. It’s very difficult, but I feel this requires us to work ‘like ants’- constantly, daily, tirelessly. The other thing I try to address is give visibility to the work of women. It’s important that people know that many women are working in science: it provides role models for young girls, and it shows the general population that we as women can be scientists and that we are successful indeed. I try that my female colleagues (my students, postdocs, etc) get visibility – that they go to conferences, that they present their work and become known. Many times they are shy about this. I know that for me it is easy to communicate science, I love engaging in interviews and doing presentations – I find it a lot of fun – including this interview for example. And I know that for some people it’s neither easy nor does it come naturally, but it’s something one can learn and get used to. There’s tons of courses on scientific communication which one can take, there’s preparation and rehearsals one can do. It’s necessary that we give visibility to our work and what we do as researchers. If we are not visible, no one can see us ☺ In Uruguay also, as far as I know, we don’t have programs that support women who are mothers – for instance in order to enable them to attend conferences. I know that now there’s changes that allow for paternity leave, additional to maternity leave. In the past, mothers took all the responsibility for the children, so now the laws are aiming for equality of conditions. But there’s still a long way to go. I see also another change: I for instance don’t have children. And I see many women now being able to openly say that they don’t want to become mothers. And society is JUST starting to perceive that this is ok, and accept these decisions. Not so long ago, if a woman said ‘I don’t want to have kids’ the reaction was more hostile perhaps – ‘what is wrong with you? Why wouldn’t you want kids?’, or ‘you’ll regret it later’ or ‘the clock is ticking and you’re not getting younger’. It’s a huge socio-cultural topic! We can’t all follow this old structure or ideology that women should get their degree, then get married, and then have children. This model is obsolete, and it should be a choice, where any decision goes. You don’t want to get married – it’s ok. You don’t want to have children- it’s ok too. But we are still questioned about our decisions! If you have children, when you have children, if you don’t have children…

And then on a different front, with the comics we also want to send this message to the girls: that they can be scientists. When I go to schools, I make a point of wearing make-up and going well-dressed, also to challenge the idea of how a scientist looks like. And within the comic itself, when we started it, the two main characters are men, and only later we realized that this was wrong. It triggered a huge discussion within our group: that we should change it so that we would have equal number of characters as men and women. Additionally, we want that the super-heroes are in equal measure, women and men. Usually in comics mostly men are portrayed as super-heroes and we wanted to change this in our project. I’ve also noticed that for the children it’s even surprising and/or impressive that the creators behind the comic include women, which is yet another topic regarding stereotypes (comic authors are not only men!).

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

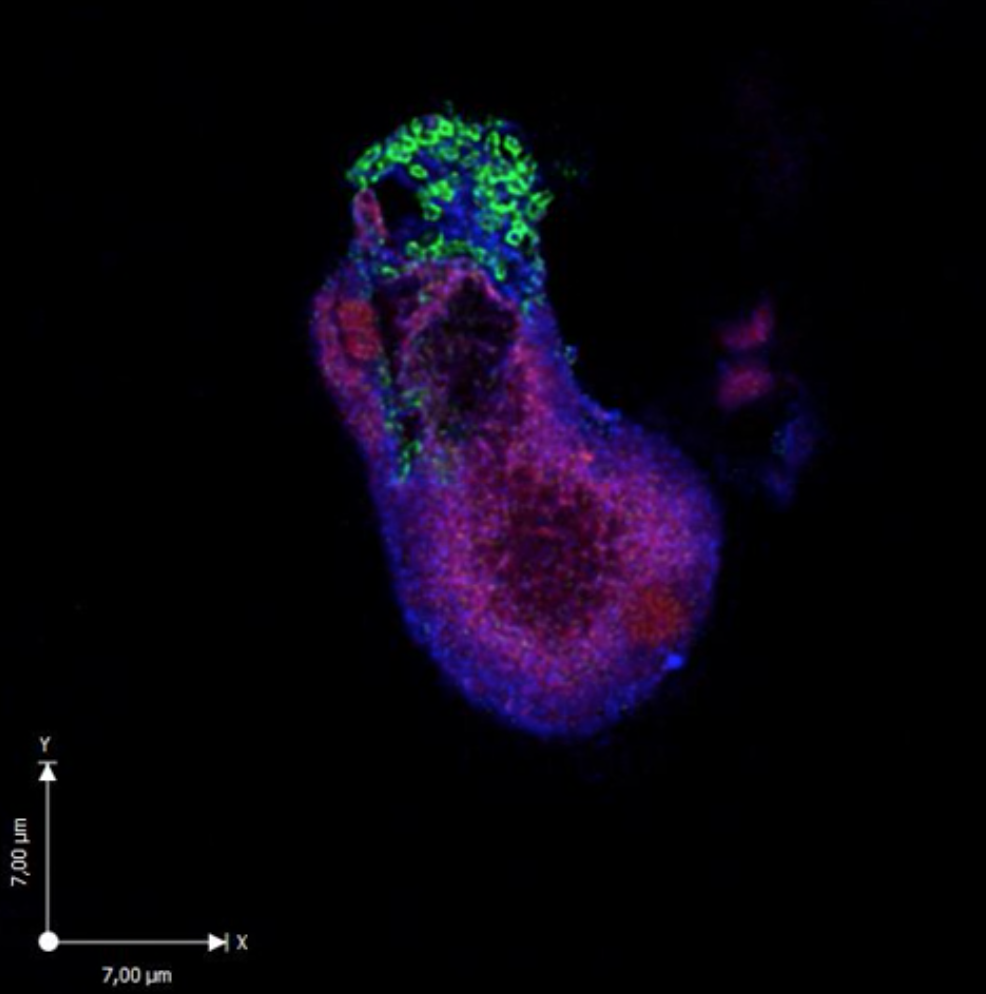

Ohhh… that’s a difficult question! My first love was the confocal microscope! I love it – it’s both magical and mystical – a microscope in a dark room where there’s always something new to find. The biggest discoveries in my career were done in a confocal microscope. I’d love to even have one at home. If one learns this technique well, it has very few limitations – you can do almost anything you want. If you know how to use the antibodies and fluorophores and dyes, the sky is the limit. And the images one can acquire with this microscope are incredible – it’s art!

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

Some years ago, when I had just finished my PhD and wondering what to do next, a pediatrician came to speak with me and told me she was working on urinary tract infections in children, and a big question she had so far been unable to answer because she hadn’t found someone with microscopy skills who could help her. E. coli is capable of entering eukaryotic cells within the bladder and forms biofilms within the cell, then stays there, and this is associated with persistent urinary tract infections. Cells in the biofilm egress from the host cell, and can re-distribute to other cells. She had the impression that in children, this same phenomenon (which was thought to be unique to women), would also hold. So we went to the microscope together – I placed the first slide on the microscope and we immediately saw that in urinary infections of children, intracellular biofilms indeed existed. That day we left the microscope with a ton of images, and were already getting ready to write a first report showing this phenomenon was true for children too. She was super enthusiastic, but then we analysed other samples from more children, and for a whole month we couldn’t see this phenomenon again. And then we made the observation again. Altogether, we imaged about 300 samples, and spent thousands of hours on the confocal microscope. We became very good friends after this intense time ☺ It was an eureka moment linked with serendipity that the very first sample we looked at was positive for what we were looking for.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Uruguay scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

My first suggestion is that if you want to be a scientist and a microscopist, you should be so. I think one has to do what one is most passionate about. Life is short so you should do something you enjoy. It’s a unique thing to be able to work on what you love. I always tell my students that the day has 24 hours – you’ll spend at least 8 hours doing your job. This is 1/3rd of your day! That’s a large proportion and you should be happy. Moreover as a scientist you won’t be a millionaire, so it’s good if the work itself is enjoyable. And then as a microscopist I think it’s a luxury! You can access things that most humans cannot access!! Microscopy has allowed me to see everything I study. You can make a trip to the inside of the cell. It gives you a whole new vision of the Universe. I know many people are passionate about astronomy and the Universe and the stars. I think Microscopy is the complement that allows us to see an unknown universe.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Uruguay, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I wish I could be very optimistic. There are various things to this question. I think science will definitely advance because there’s a group of humans that is pushing it forward. We need better financial support – without it, there’s no future for science. Each year, the state distributes funding across various sectors, and it’s painful for me to see science being so neglected, especially after the pandemic when many politicians came out to say ‘Uruguayan scientists are great, and we owe then a debt of gratitude because of the important job they’ve done’ but when we ask for money to do science, we receive so little. I think for the population it’s much clearer. The bigger gap is with the politicians. Perhaps it’s that we as scientists are failing in conveying the message and have not yet been convincing enough on why scientific research is important. Also, for politicians it seems it’s difficult to grasp that basic science is just as important as applied science – without basic science, there can be no applied science. They tend to focus on an end product, and don’t realize that a lot of basic knowledge (which does not directly result in something tangible like a drug or a vaccine) is needed to reach that end product. Science is a job that is slow, and it seems we are missing a mediator or inter-communicator that can transmit the messages between scientists and politicians. I understand also the politicians’ point of view and that they need to address various questions from various fields and need to deliver tangible things within specific time frames. They want things to be immediate, and science hardly works like this. Additionally, I think there’s a fault even in how we are expected to communicate things to get funding or publish papers: there’s an obsession with ‘novel’ and ‘paradigm-shifting’. My work is much more valued if I sell it as ‘I am going to solve the problem of anti-microbial resistance’. This is a lie! I am trying to generate enough knowledge to reach this point, but not every piece of work I do will directly ‘solve the problem of anti-microbial resistance’. But it seems that in order to get a politician’s attention, one has to be a salesman/saleswoman who says he/she will solve the problem altogether. If I tell the politician that I am going to use the funding to study the molecular basis of biofilm formation, it’s unlikely he/she will understand or see the relevance. I think for the general population, it’s easier to understand something tangible than basic knowledge. And I think this falls back on the need to communicate and educate the general population on what science is, and the value of knowledge beyond a product like a drug or a vaccine. On a different topic, I see that foreign scientist are coming to Uruguay to become scientists as we have Public University and you don´t have to pay for a PhD or Master. I think we are becoming a hub, and this is a good indicator. I think we all have to work every day tirelessly, until we don’t have to talk about economic difficulties and political issues affecting science anymore.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Uruguay a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

Mate!! ☺ I think Uruguay has two nice things: Uruguayan people – who are very welcoming and very relaxed, and the fact that everything in Uruguay is very relaxed and peaceful. Some people love this peacefulness. Sometimes I wish more exciting things would happen, but it’s nice that we enjoy this peace. We have 672 km of coastline. One can enjoy nature – it has many beautiful landscapes.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)