An interview with Lucía López

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 18 October 2022

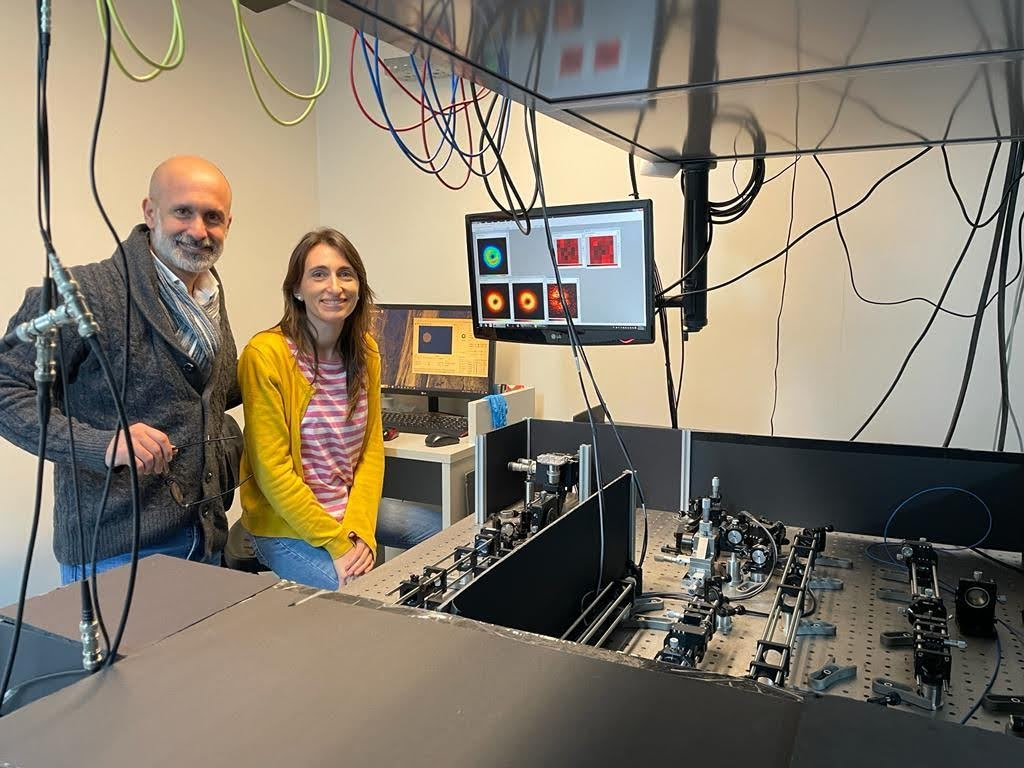

MiniBio: Dr. Lucia Lopez is an Assistant Researcher and senior postdoc in the lab of Dr. Fernando Stefani at CIBION (CONICET), where she works towards establishing novel technologies for super -resolution microscopy. She studied her BSc in Physics at the University of Buenos Aires in the lab of Dr. Silvina Ponce Dawson, where she first became interested in calcium signaling. In 2018 she started her postdoc in Dr. Fernando Stefani’s lab, where she specialized in super-resolution microscopy. Lucia recently participated as a selected speaker in the 2022 Latin American Bioimaging meeting that took place in Montevideo, where she shared the personal story behind her scientific path as a scientist.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

It’s interesting. Growing up I used to live very close to the Faculty of Law, and my dad often suggested that I should become a lawyer because I would earn a lot of money and I would be able to study close to home. About when my love for science started I’m trying to think about it… During my high school I had a French teacher who was truly great. She used to teach Physics and was super passionate about it. And the other person who inspired me a lot was my mother. She is a researcher- a Physicist for 45 years now. She worked a lot on solid state Physics, and specialized in Raman spectroscopy. She wasn’t the stereotypical scientist-parent who brings science books home and takes the children to the lab all the time. She didn’t do that – my mum never brought the work home. But she always showed us that her job made her very happy. I think this is a very important message. Anyway, when I finished high school I enrolled in University to study Medicine. They gave me a tour around a hospital and here I realized I was not really interested in Medicine or diseases, but rather about the equipment. I kept asking ‘What does this do? How does it work?’ and then I wondered whether it was truly Medicine that I had a vocation for, or rather Physics. I decided it was Physics.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

My love for Microscopy came much later because in the degree, at least in Buenos Aires, we didn’t study Microscopy this early on. We studied Optics, but not microscopy as they do in Chemistry and Biology. I had a chance to join Dr. Silvina Ponce Dawson’s lab in Buenos Aires, in the last year of my BSc degree, to do a project on Biophysics, focusing on calcium imaging, and this was the first time I did microscopy. Her work was much more theoretical though – dynamic systems. I worked on the experimental part. This first approach was rather random: microscopy was the most adequate tool to address the scientific question and that’s how I came in touch with this discipline. And while I enjoyed it, both during my BSc and then PhD (which I also did in Silvina’s lab), I saw microscopy as a tool rather than as a topic I was most interested in. This came a bit later. I think I became passionate about microscopy only when I joined Prof. Fernando Stefani’s lab as a postdoc. All my focus ever since has been on Optical microscopy: confocal microscopy, super-resolution, etc, and very little on electron microscopy. When I finished my PhD, I almost went to Barcelona to do a postdoc on a totally different topic. In the end I joined Fernando’s lab, and have been in his lab since.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Argentina, from your education years?

My early education was not 100% Argentinian because I went to a French school. But one thing I find great about the education system – for instance once I started University, is that it is free. Uruguay also has a completely free education system, but this is not the case in many other countries, including some in Latin America. I find it shocking that in many countries around the globe you either have to get a huge loan to be able to study, or come from a wealthy family that can support you during your studies. This is not the case in Argentina. Of course, this still does not mean that everyone has access to it even if it is free– we have to be conscious about privilege and how this impacts accessibility. But still, in Argentinian Universities, this means that you get to meet people during your career, that come from all sorts of backgrounds, and it’s a great opportunity to learn many things. Still, I find it essential that one does not finish higher education with a debt that will take decades to pay. This would limit access even more. And I had this discussion even with friends and colleagues from abroad, for instance when I went to the USA, and they were surprised that I wasn’t in debt.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a postdoc and lab manager heavily involved in microscopy?

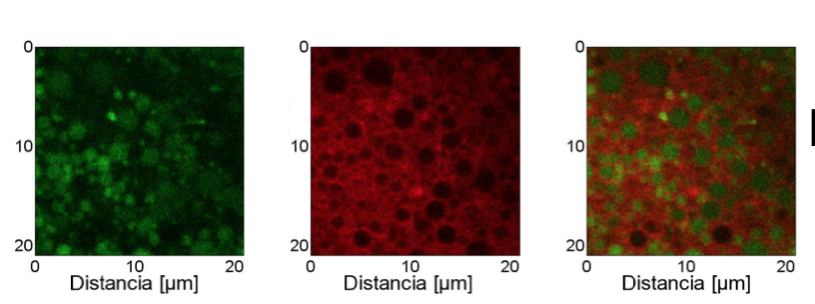

I started my postdoc in Fernando’s lab in 2018, with views that it would last 2 years, but half-way through 2019 I took a leave of absence because of a high-risk pregnancy, then I had my baby and went on maternity leave. And by the time I came back, the COVID-19 pandemic started and we were all sent back home. It was altogether a very short postdoc, but then a vacancy opened for a role of CPA (Carrera del Personal de Apoyo) for research, which is a sort of permanent position as a type of lab manager. Perhaps the description of the role does not really match my daily activities – my role in the lab is much more like a senior postdoc – I’m the one who has been longest in the group, and the one who is most familiar with the vast majority of techniques used in the lab. I play a supervisory role with the PhD students and am available to help with whatever they need. I’m involved in all the projects of the lab using super-resolution, and I’m in charge of purchases for the lab, and the daily management of the lab. I’m about to write a new methods paper. Basically a senior postdoc with managerial duties too. In terms of the projects, we have very nice collaborations with many other groups in Argentina. At the moment we are finishing up a project which involves imaging two proteins (probably the first time super-resolution is used to observe transcialidases and mucins) on the cell membrane of the parasite T. cruzi. We are collaborating with a group focusing on Biochemistry who want to study mechanisms of immune evasion displayed by the parasite. Here in Argentina this is quite relevant because Chagas disease is highly prevalent. In addition, we have close collaborations with groups working on neurosciences, specifically looking at the MPS (membrane periodic skeleton, which is an actomyosin network whereby actin rings are interconnected by spectrin). It was discovered not so long ago, and we are interested in seeing how it works in healthy neurons as well as diseased ones. We image them in cell culture, and even in situ, in tissues extracted from mice. We have other collaborations that are slightly paused at the moment – several groups propose collaborations with our lab to do super-resolution. The problem is that currently we are limited in terms of time and human resources – we can only do so much. You know how it is: it’s not just coming to the microscope and taking one quick image. Imaging alone takes a lot of time, and most of the times one has to adapt the microscope for the research question being asked, so it takes months. We have to limit the collaborations to the closest ones.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Argentina?

I don’t think we collaborate as much as we could. This is something that needs to improve in the region. I feel something common in Argentina is that we are taught to believe that the ‘great’ science is happening in the USA or in Europe, and to ‘look North’ instead of fostering collaborations with our neighbours. Sometimes we even read about the work being done in the Global North and we don’t even know what is being done in the region. One just has to cross the river to Montevideo and there is great potential for collaborations – very close by. But in terms of collaborations in the region, I went to a very nice course on systems biology, organized by the Pasteur Institute in Montevideo. And now the Latin American Bioimaging meeting that took place a few days ago. I think this was a truly wonderful event and I hope it helps improve the collaborative spirit in the region. Also I’ve noticed that many Latin Americans who leave the region (i.e. the diaspora), form strong networks abroad of course. There’s also a prejudice for instance towards Latin Americans who go abroad as PhD students or postdocs, and then return to Latin America to start their own groups – as if somehow they ‘failed’ in making a career abroad in the Global North.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Argentinian researcher, working abroad?

During my PhD I went to UC Irivine, and I’ve attended several courses, mostly in the USA. Something I noticed that just like in Latin America there’s this idea that better science is done in the Global North, in some countries of the Global North there’s a prejudice that in Latin America we don’t do high quality science, or that the standard is lower than in their regions. It might not have been a direct thing, but you could see it. I got asked things under the lines of ‘you can do that complex technique in Argentina?’ with a tone of surprise or disbelief. Also, my PhD adviser opened my eyes to this too: there are now systematic studies which have shown the bias that exists in publishing houses: when the same piece of work is submitted from a ‘big name University’, as opposed to, say, a Latin American University, it will have better chances if it’s submitted from the ‘big name University’. It’s a brand of credibility, but this is all prejudice.

Who are your scientific role models (both Argentinian and foreign)?

Obviously the two people who were most involved in my formation are my role models: Silvina Ponce Dawson is one of them: she opened my eyes to all the biases and all the politics of science, and she is very vocal about issues regarding diversity equity and inclusion. She was chair of Women in Physics. Also as a scientist she is exceptional, and as a person too. And my other role model is Fernando Stefani. He is great as a scientist, as a group leader, as a mentor. It’s very stimulating to work with him. In addition, I must say that my new role models are the PhD students I’ve met and worked with in recent years – Luciano Masullo and Cecilia Zaza for example are amongst the people from whom I have learnt most in recent years. They taught me the value of working in a team – when I did my PhD I was pretty much alone, but when I joined Fernando’s lab, I noticed that it’s wonderful to work in a team. It’s a place where everyone helps one another, and there’s a strong team spirit. It’s very stimulating! I think this is the main thing they showed me: there was no competition, but the total opposite. And they are very capable and resourceful- from hardware design to software design, modelling, sample preparation, everything. Scientific advances, at the end of the day are never the result of one person’s efforts, but the collective work.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Argentina, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I think in Argentina we’re doing better than in other parts of the world, but it’s not enough. The gender gap is very real. There are explicit things and implicit ones – it’s not enough to have laws that force certain changes, but this needs to be accompanied by a socio-cultural change as well. For instance, I am aware that in some countries in the Global North, paternity leaves are approved by law, but there’s still prejudice regarding men who take this time off. As if it’s wrong to do so. It’s frowned upon if a man stops working when you have a child. So despite the ‘law’, the socio-cultural change is lagging behind, and real change fails to happen. I have also friends in countries of the Global North who still see a huge dominance of white males above a certain age, with very few women in positions of power. This is perhaps less obvious in Argentina, fortunately. We have much better balance. But we still face the glass ceiling. Positions where decision-making is done still lack female representation. In terms of my direct mentors, Silvina was amazing and for me it was great to work with her -she opened my eyes to these important issues that have a huge effect on our work at the end of the day. Fernando also was always extremely supportive to women. At the end of the day, I know I am lucky with the mentors I had, and that not everyone is so lucky. And then there’s another issue even within science: for the ‘hard’ sciences like Mathematics, there’s still a lot of ‘prejudice’ that these are subjects for men, while disciplines like Biology are for women. We need to change this perception much earlier – with younger children. This impacts many careers, like Naval Engineering or Petroleum Engineering where the number of women is really minimal. I teach some classes of Physics in these careers, and there’s perhaps one woman for every 20 or 30 men. My take-home message is that there’s a lot to be done. But even in the region we are relatively progressive. We are one of the few countries of Latin America who has had a woman president, thrice. We also now have egalitarian marriage. In this sense, it’s a much progressive situation than in other countries in Latin America.

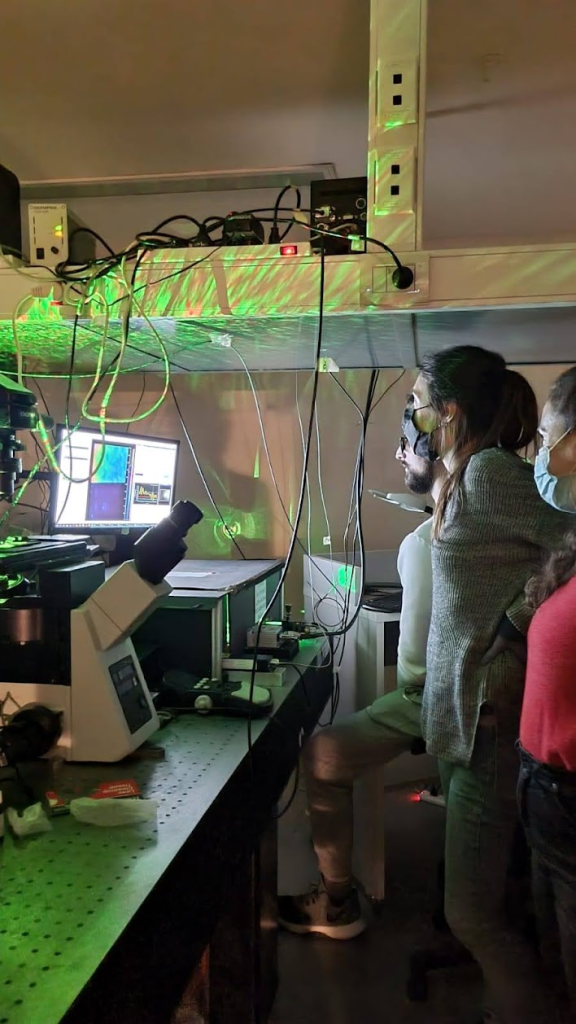

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

Fluorescence microscopy is my passion – I love to be able to look inside cells. It’s amazing when you turn on a laser and then see something extraordinary. More specifically, among the techniques coming out in the last few years, my favourites are MINFLUX and RASTMIN. Although you don’t have the magic of the image right away, and you just have some noise from pixels, later on you get to see single molecules, localized with a 1nm precision, it’s incredible. When I did my PhD I did live cell imaging too, and this is also extraordinary! To see a living cell performing its various tasks in real time. Maybe in the near future we will be able to do this in my current lab 🙂

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

I don’t know if I have an eureka moment. Let me think. Perhaps in my PhD, I used to work with live cells, and preparing the cells took a lot of time, they used to die all the time – it was all artisanal. I used to look at calcium signaling in the cytosol and the reticulum, so I would use two markers – it was difficult to work with, and when I managed to see some signal, I remember thinking “this PhD is not in vain – there’s something interesting happening here”. It was all very challenging. Perhaps I would describe this as a relief, rather than an eureka moment. Later in my postdoc lab, there are tons of routine things that are eureka – it’s all related to hardware working the way I want it to, so it’s more like mini-moments.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Argentinian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Study hard, don’t give up, surround yourself with other young people who share their enthusiasm. Ask lots of questions, network, knock on all doors, don’t accept everything you’re told as fact. And here in Argentina, really don’t give up – things are unstable and things change every 2 days. So if the career in science and microscopy is what you really want, keep your eyes on that target – this will help you navigate this instability. Be patient. You need lots of patience in this career too.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Argentina, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

Argentina right now is in a terrible moment, financially speaking. I see the near future a bit stormy because financing is restricted for sciences. Resources are very important – not just for purchasing things, but for training people. And right now it’s really difficult to recruit people. For instance, fellowships are really low, and really limited so recruiting PhD students is becoming more and more complicated – they choose more secure jobs rather than a huge uncertainty that will last 5 years. In this sense I don’t see how science will develop, but I don’t lose optimism. I hope new people will join, and with the formation of networks such as LABI, I think this will help a lot. But while we have to enjoy what we do, we should also be guaranteed livable wages. With ‘vocation’ and ‘passion’ you don’t pay the bills at the end of the month. Besides of the wages, we should have the right to a life! Being able to do activities outside science. I think one’s career and one’s life should be compatible and complementary, not exclusive. I feel there’s the old school way of thinking in which a scientist must sacrifice everything – and this is obsolete. I don’t think it should be like this. Science is currently very exclusive – that’s why it selects for very specific type of people, and this exclusivity is wrong.

In terms of attracting talent from the ‘diaspora’ back to Argentina, we have a program called ‘Raices’, which facilitated the return of scientists if they wanted to establish their labs back home. But right now the lack of funding is making it very hard for people to come back, even if they wanted to.

What I hope to contribute is to make my expertise available and contribute to accessible and equitable science. All hardware is open source, and for instance I am currently writing a protocol on how to optimize the setups to do MINFLUX. I think all these techniques should become accessible to people with not so many resources.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Argentina a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

The people! Argentinians are very warm-hearted. We are very ‘permeable’ – it’s easy to belong, and we approachable and warm. I think we share this with many other countries in Latin America. Moreover, the natural beauty of the country is very attractive.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)