An interview with Andrés Hugo Rossi

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 6 December 2022

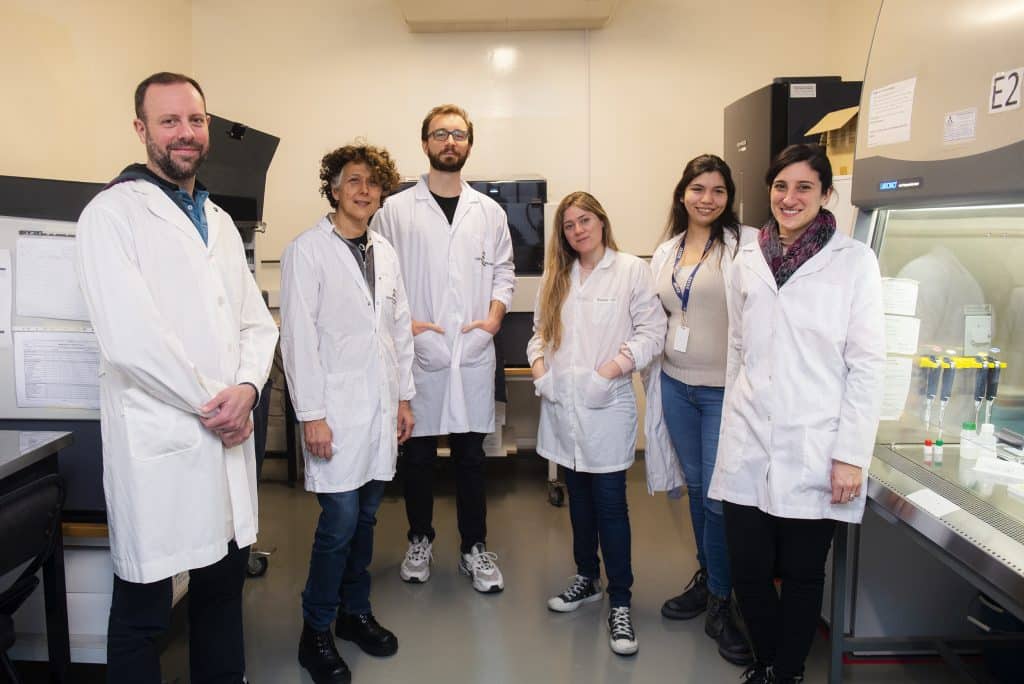

MiniBio: Dr. Andrés Hugo Rossi is the Imaging, Microscopy and Cytometry Core Facility Manager at the Leloir Institute in Buenos Aires. During the COVID-19 pandemic he spearheaded the creation of the Laboratory of Serology and Vaccines at the same institute. Andrés began his career in 1997 as a chemical technician in the pharmaceutical industry. Later, in 2010, he finished his undergrad studies, obtaining the title of Biochemist from the University of Buenos Aires. He continued his formation as a healthcare professional at the Garrahan Pediatric and the “del Quemado” Hospitals. He also obtained his Master´s in Data Science from the Buenos Aires Technology in 2018. He began his research career in the area of virology and then focused on immunology, obtaining his PhD at the Laboratory of Immunology and Molecular Microbiology of the Leloir Institute. Since 2018 he holds a tenure position in the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) as a Principal Professional in charge of the imaging facility, where he impulses the continuous development of techniques, equipment and the research projects of users from other laboratories. As head of the Laboratory of Serology and Vaccines his team provided quality scientific evidence for decision making in public health at a national scale.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I was always a very curious child. I always wanted to have an answer for everything: how my electric toys worked – I asked my family how they worked, and they would explain to me the basics. As my questions increased in complexity and they could no longer explain things, I opened these toys to try and figure it out myself. In high school this curiosity led me into being drawn to Chemistry. I entered a technical college which in Argentina are known as Colegios Técnicos. From there I graduated as a Chemistry Lab Technician, and this increased my understanding of life sciences. I then realized I wanted to understand how we as humans, work. For instance if I move my hand, I wanted to know how it is that the hand can move. So I started looking for possible careers as a BSc, and joined Biochemistry. It included Physiology, Anatomy, Genetics, Cell Biology, etc. I think Biochemistry was the career that got closest to answering all the questions I had about life and human functioning.

You have a career-long involvement in virology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose these paths?

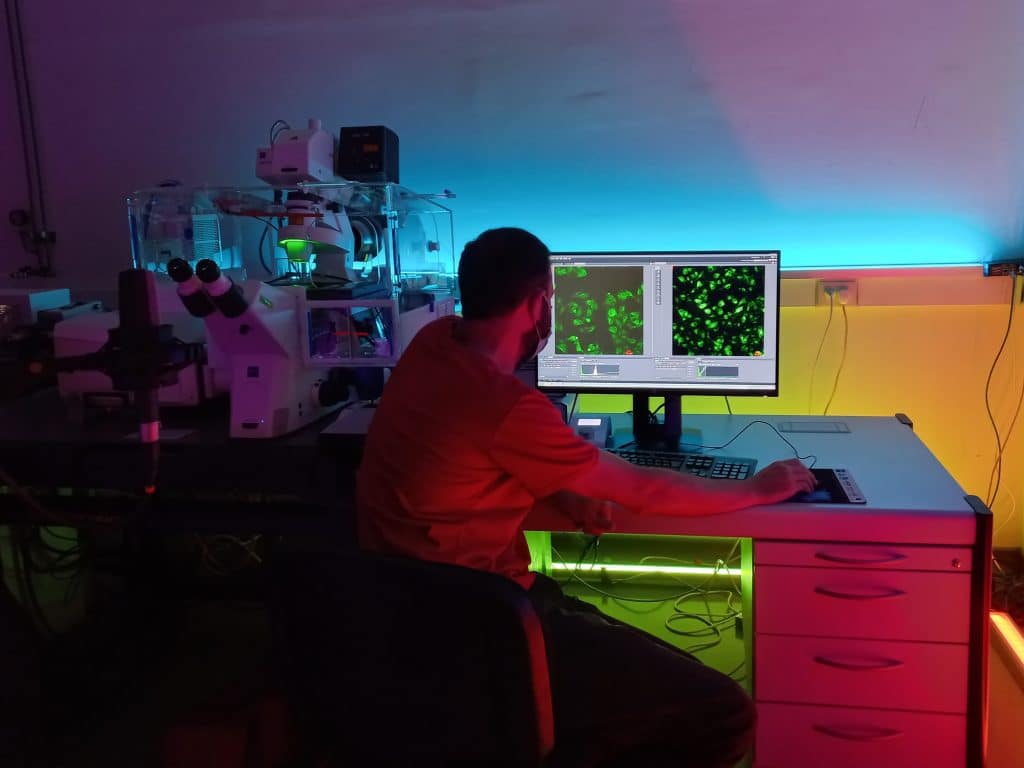

I did my career sort of the other way around. Because of my technical career, I started working as a Chemist when I was 17 years old – around the end of the 1990s. I had a stable job at a North American company – Allergan, a cosmetic company which worked with Botox in Argentina. I was working in Quality Control. When I started my 1st year of my undergraduate degree I was unable to keep up with both things – the job and the degree, so I dropped out of University for 4 years. I kept working, I managed to get financially stable and save enough money to be able to afford to go back to University. I went back at age 25 to complete my degree as a Biochemist. By the time I finished my BSc degree, I had 8 years of experience as a Chemist in the Pharmaceutical Industry. What inspired me to go back to University was my sense of curiosity. At the Pharma company I got a bit tired of the standardization – at the time the ISO9000 standards had just started being implemented, and I was involved in this part. But I missed the creativity part and more challenge in terms of intellectual stimulation. At 25 years of age I realized I did not want to work like this for the rest of my life. Despite it being a stable job and being so lucky to have it at such a young age, I still took the leap of faith and tried the BSc degree in Biochemistry. I think this decision was excellent. I finished my degree much older than the rest of my colleagues and in Argentina the scientific opportunities decrease as you become older. Access to funding – fellowships and grants to do a PhD – is age restricted, sadly. Also, since I had done my degree in two parts, my grade point average was not super high because of my grades in the first year, so this also affected my chances. Once I finished my degree, I started working in at Hospital de Pediatria Garrahan, on HIV research. I worked in one of the first groups in the country to study HIV, but this was all with small grants and short internships. But around that time the Hospital was recruiting Biochemists to work at the Emergency Labs, and since my degree was in Biochemistry I was able to join. Emergency Labs are the labs operating at all times of the day, and throughout the year (including all holidays and weekends). They always need people because professionals who raise in the ranks eventually don’t want these jobs anymore because of the tough schedules. But it’s a very well paid job and it allowed me to work both in research (in the HIV lab), and to get a salary. This was the beginning of my career. I think working at the Emergency Lab gave me a lot of perspective of the bigger picture – when you get a sample a see that it’s coming from a person with a certain condition, it can be tough. I think sometimes when you do research in a different context working with some recombinant protein, you don’t get this perspective. It’s different when you are, say, measuring proteinemia from a pediatric patient with a malnutrition complication. It gave me a very human perspective. I was happy I was able to contribute in the health chain, to help people in situations of health emergencies. Eventually another hospital started recruiting Biochemists – the hospital specializing in burns. This hospital was very small – small enough that Biochemists were involved all the way, from the patient’s entry to emergencies in an acute state. It’s very tough, but also it meant we could all contribute to help the patients. After 15 years working in Emergencies I finally moved on last year. I felt I could no longer do it, and I could no longer manage all the work I’m involved in. To supplement the very low fellowship salary, I worked as a Biochemist on weekends and holidays. But this double life was easier when I did not have children and had more time at my disposal. I had a lot of support from my family too. I did my PhD later on, and although I loved it and found it incredibly inspiring, I felt that the ‘dream’ of becoming a PI and having my own group was not really my dream. Having worked in industry and in hospital settings I had inputs on how ones career can be different. Doing basic research was not fulfilling enough for me, and I figured out there were other ways of raising hypotheses and answering scientific questions beyond the academic context. I went on to study a MSc in Data Mining. Around the time of my PhD I came across Microscopy for the first time and I truly loved it. The confocal microscope again triggered my curiosity. I found the concepts of optics incredible. I did a small postdoc in the same lab afterwards, at the Leloir Institute, another position became available as a Facility Manager of the Bioimaging Unit. Around that time we had 9 microscopes – there was a lot to do, and it was a truly appealing job, so I took this position. I remember when this position became available I had an offer of another position in Industry working on genetic improvement of seeds and data mining. I had all the qualifications – it was a private company with a very good salary but I had the other offer to become the Head of the Imaging Unit. Again, my curiosity dictated the path – I imagined all the possibilities as Head of Unit – being able to explore all these microscopes, explore and establish new methodology, and help others investigate their research questions. It was a thrilling idea and I decided to take the job. I started this job in 2018. All the groups were looking very much forward for someone to take this position and contribute in this way to the institute’s scientific output, and they were all very supportive. Right before I took the position the institute acquired a Zeiss 880 with an AiryScan unit which was completely new – the first microscope of this type in the country. I was super excited. This service hasn’t stopped growing – we generated the Cytometry Unit and now what I’m trying to nucleate various units together to provide a more complete service: these units are histology, cytometry, microscopy and cell culture. We provide service to our institute, but also the unit has become a resource for other institutes too, at affordable costs. At the time this service is mostly used by various institutes in Buenos Aires, but we are open to requests from the entire country. In terms of microscopy, I was mostly involved in developing the facility rather than specific topics of research.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Argentina, from your education years?

Education in Argentina has a mixture of very good professionals – scientists and teachers – who make a huge difference. However, the quality of teaching has dropped a bit because of lack of resources, which I think is a world-wide phenomenon that needs to be taken seriously and addressed. Nonetheless, there are many inspiring people who are willing to make changes and give 100%. There are also problems in terms of bureaucracies typical of Latin America probably. Moreover, I think in Argentina, a lot is up to the student – nobody helps you navigate the system. But this of course teaches you independence. On the other hand this support needs to improve. I have a personal example on how this can impact people’s lives: when I started University the first time, I arrived to an exam and I told my professor I had been working a lot and had not had time to prepare for the exam. Of course this was not correct, but it wasn’t out of irresponsibility – I needed to work to sustain myself. She told me “Look, either you work or you study, you can’t do both and you have to choose”. She just showed this sort of binary decision. I wasn’t a bad student, and I think more support could have been given – to take the exam later on or so. I think this sort of attitude starts making a differential of who can proceed and who can’t, based on resources. Studying is very expensive even with public education: you still spend money in transport, in books, in printouts, etc. I think when one has scarce resources, one’s formation or education is very different. Still, many excellent researchers receive their education in the Argentinian education system, and when you compare the standards to those in the Global North, we’re not that far behind. There are excellent professionals, and this gives me hope. Moreover, having worked in international environments, and diverse labs, I feel everyone contributes their own experience, including one based on financial resources. I have noticed that this particular experience (of course together with many others) can result in different solutions being proposed, which I think is an enriching experience.

Can you tell us a bit about your role in the creation of the Laboratory of Serology and Vaccines during the COVID pandemic?

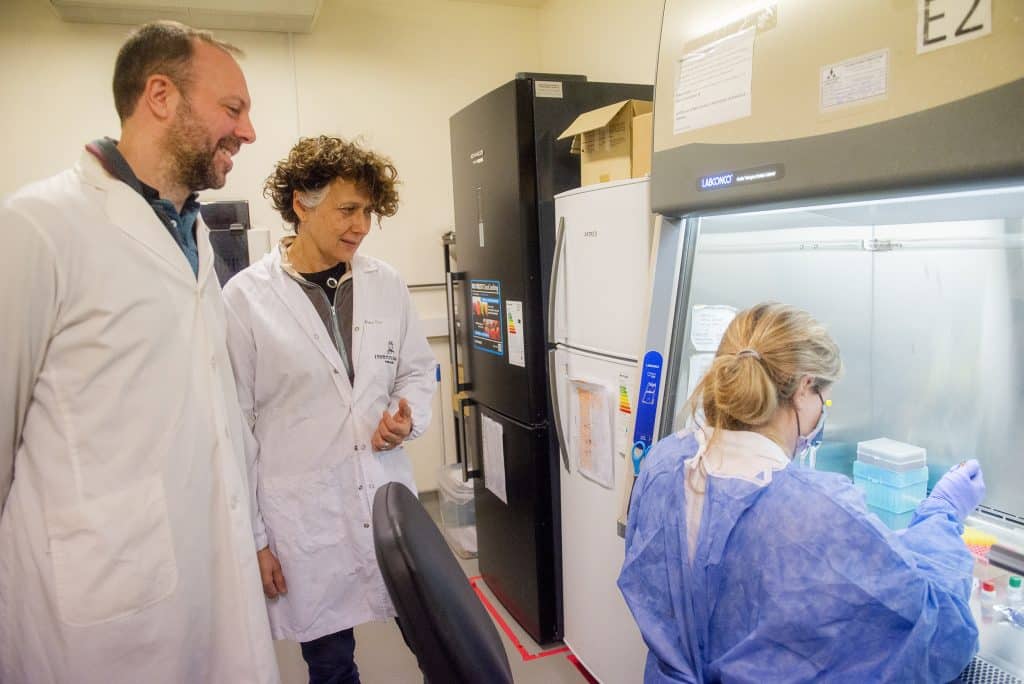

During the COVID-19 pandemic I was contacted by the Health Department of Buenos Aires, to put together some teams to help the geriatric homes, because whenever someone was infected in these homes, it was a disaster – it would result in significant loss of life. So the Ministry of Health tasked us to do IgG/IgM antibody tests at the centres as a way of surveillance and sort of prediction on a weekly basis. In addition to the scientific work, I saw here the importance of scientific communication – I explained how the immune system works, how a vaccine works, how viruses work, and other biological concepts multiple times to the health personnel, the nurses, the geriatric assistants, the people at the centres, and the general population. People were very motivated to really help avoid the spread of the disease. Meanwhile at the Leloir Institute, Andrea Gamarnik, who is one of the most renowned virologists in Argentina, as soon as the pandemic began, she gathered her team and together put together a plan on how to help the population. They developed the recombinant, optimized an ELISA, and put together a kit called COVID-AR. They made a seroprevalence study in Barrio Mujica – it was a huge contribution. At the same time one of the largest geriatric homes in Buenos Aires asked me to do a seroprevalence study there. I told them I would write to Andrea to get the ball rolling. I thought she would not reply, but she replied within 2 hours – she gave me her mobile number and asked that we chat. She said PAMI (Instituto Nacional de Servicios Sociales para Jubilados y Pensionados – the Institute for Social Services for Retirees and Pensioners in Argentina) had approached her, asking for her support. Andrea asked me if I could help and I was 100% on board. PAMI’s request was to use the COVID-AR test in the centres for retirees, pensioners and disabled people. Together with Andrea we realized we had to put together a lab dedicated to assist the population. Building a lab from scratch wasn’t the original plan, but I called several health centres, hospitals, etc – everyone was overwhelmed during the pandemic. We spent one month trying to get external support, and eventually decided we should create this lab ourselves. I spoke to Angeles Zorreguieta, the director of the Leloir Institute and asked her if we could use one of the labs in the institute. This eventually became the Laboratory of Serology and Vaccines. We were 17 volunteers and within 1 month we were processing 500 samples per day, as a taskforce supporting the requests from PAMI at a rate that would really enable us to identify positive cases almost right away, and prevent the spread of COVID in the homes for the elderly. Between August and December 2020 when there was a lot of uncertainty of when and whether we would get the vaccine in South America, Argentina managed to acquire the Sputnik vaccine. Around this time Andrea was contacted again by the Ministry of Health, saying that the vaccination campaign was going to begin but they wanted to build a surveillance and control plan to follow up the results of the vaccination campaign. Around March 2021 we published the first results of the effects of the vaccine on the Argentinian population. This was all serology report doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100359. Further work from the lab also helped inform decisions about the booster vaccine, and about heterologous boosters, about the results of the 2nd booster (3rd vaccine), antibody prevalence. Altogether the package coming from this lab was 6 publications (doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100359, doi: 10.1128/mbio.03442-21, doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00176-1, doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00427-3, doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100706, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.992370). The main aim of the lab we generated was to give support to the Ministry of Health, and nowadays this lab is being transformed into a critical part of the Leloir Institute. Currently, the idea is for the Lab to have a translational focus, and to serve as a bridge between research, diagnostics and clinics. There are many local pathologies and diseases affecting the Argentinian population that could benefit from this resource. The Lab now has to evolve with time, because the state of emergency during which it was created is no longer the reality. It’s not impossible that something like this pandemic happens again, but the Lab needs to ‘mutate’ into something sustainable and affordable. The government will only continue to provide funding if the Lab addresses an important populational need. It will be an interesting challenge. Speaking with Andrea, we discussed how the COVID pandemic brought together the general population and the scientific population, and that this was an opportunity for scientists to put together proposals for how the general infrastructure for preparedness could improve. So now the challenge is to keep the momentum of this Lab! 🙂

You have a very versatile career – can you tell us a bit more about how you see your work, and what makes you tick?

I love learning new things constantly. I get bored easily, and this has a huge impact in my work. I love to address challenges that are unsolved. I feel this has been a constant throughout my career – with the Imaging Unit, and later with the COVID pandemic – I see a problem to tackle and I go for it. For instance, I think that having a good Microscopy Unit has an impact that irradiates to all the research groups, regarding whether it’s cancer research or viruses. Everybody wins if we do this investment in terms of organization, time, and resources. Recently I saw this open call for Project Manager in CZI and found it very appealing. Having the chance to contribute to a general project and aims like those of CZI is a fantastic opportunity. But when you think about a job abroad, you should consider your family too.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Argentina?

Yes, but I think there is room for improvement. I have had more opportunities to collaborate with people in Europe and the USA.

As an Argentinian scientist, did you have any challenges working abroad?

I have lived abroad several times. The language is the first barrier – in the Argentinian education system, English is not included as a key thing – it’s usually an extracurricular activity. So this is indeed a challenge. When I lived in Lille, France, the language was also a challenge, but I was lucky because I met people who were very welcoming. After my stay in France, a few of those friends even visited Argentina – we built very good relationships. Another challenge is being far away from my family (parents, siblings, etc). Now that I have my own family, despite the fact that I would like to go abroad for a longer amount of time, it’s a huge challenge. We have small children, and my wife pointed out that removing the children from their culture, and away from their grandparents, cousins, etc, will be difficult. So we haven’t made this step.

Who are your scientific role models (both Argentinian and foreign)?

Historically, we have a few Nobel prizes in Argentina – there’s Bernardo Houssay and Cesar Milstein who are like lighthouses of how far one can reach. A more current/modern role model for me is Andrea Gamarnik – I had the chance to work with her during the COVID pandemic and it was like playing with the top football league. It was a fantastic experience – her qualities as a human being, and her intelligence as a scientist are out of this world. She’s incredibly smart, and she potentiates everything around her. She asks herself (and others) a lot of questions, in order to reach answers and improve things, and move them forward. Other than this, I also admire people who manage to achieve a good work-life balance, wherever this is. I think being able to do this is admirable. In Argentina this culture of work-life balance is still not healthy. There’s still a culture of ‘workoholism’, and additional hours are not often paid. The COVID pandemic led to several changes because of hybrid work modalities, but this also needs a balance – what you don’t want is now be expected to work 24/7 simply because you’re working from home. There needs to be a balance.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Argentina, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

My main role model is a woman – Andrea Gamarnik. I think there shouldn’t be a difference in terms of gender – what matters is one’s intellect, one’s passion, one’s wish to contribute. Also, in Argentina the feminist movement continues to advance: the most recent achievement was legalizing the right to have an abortion. I think this was revolutionary. My wife pointed out recently how exciting it is that our children will live in a different world to the one we lived in (with different prejudices and paradigms and social rules). I think now we need to defend what we have achieved and improve the things that are missing. I think the important thing is that now we can do things that were previously forbidden (and which were oppressive to women). I think we are still not a balanced society, and there is a huge amount of work to do, but I think we have been moving forward in a way that is truly exponential. For example in one of my children’s group, there is a transgender child who made this transition recently. The school was very supportive and all the children were supportive. It wasn’t seen as an anomaly or something strange. It was completely natural. And this allowed the child to focus on her own needs, not on ‘what will people say?’. But I acknowledge that not all schools would have reacted in this way – there’s still a long way to go.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

I love confocal microscopy. I love it because of its simplicity! A simple pinhole!

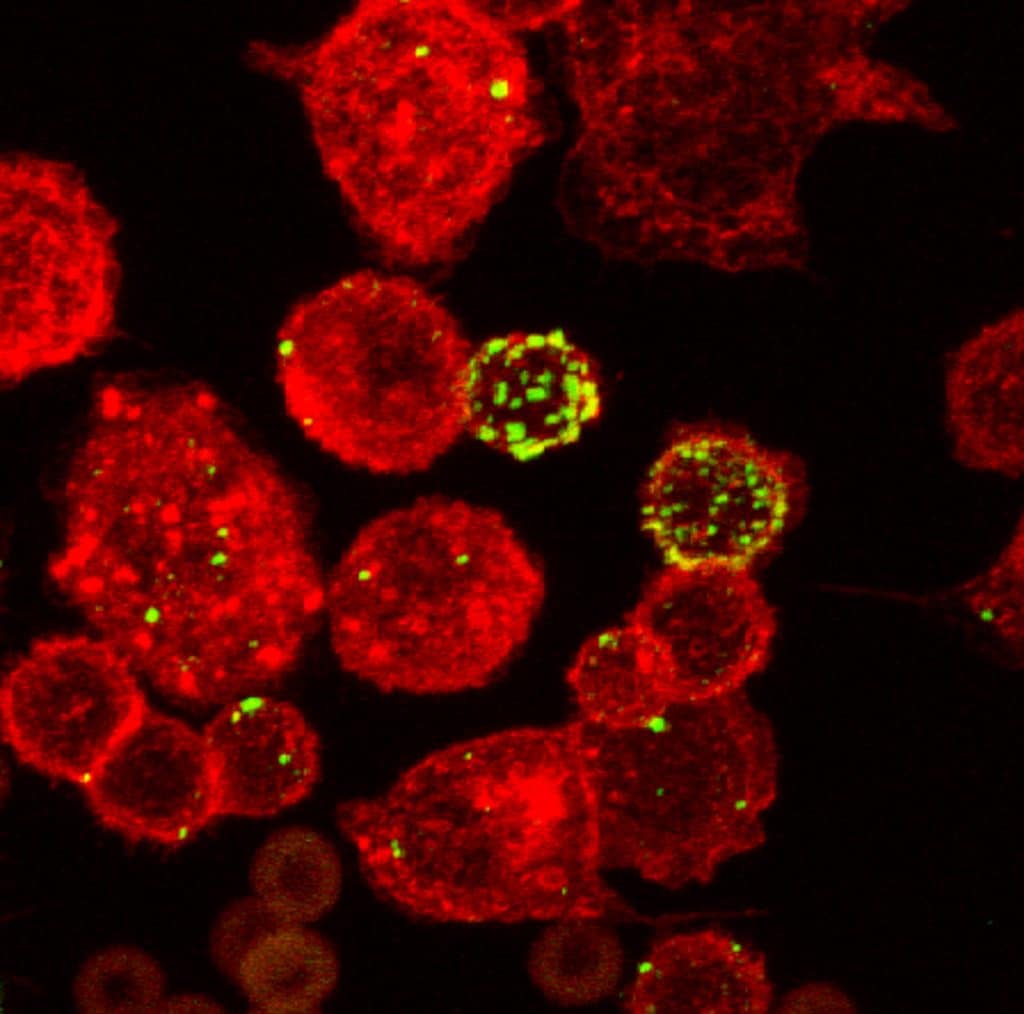

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

A 3D reconstruction of a dendritic cell – I wanted to see how a labeled protein attached to the DC’s membrane. I took a z-stack and when I managed to reconstruct it, the three-dimensionality of this phenomenon was fascinating to me.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Argentinian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

I think a microscopist needs to be versatile. There is no career of microscopist per se, so you need to know about Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Computer Science. Look for good training opportunities, and for the best places. Lose the fear – ask for chances to do an internship or a position as a student or postdoc. Explore all possibilities – keep an open mind. Don’t stay all the time doing the same.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Argentina, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think in Argentina a big challenge for the future is the country’s economy. It’s very unstable. I remember my parents telling me how each generation (their parent’s parents, their parents and themselves) has faces a major economic crisis. There is a lack of continuity in the political and economic systems. There is a National System of Microscopy which is consolidated and has survived all these external fluctuations. It’s based on the premise of sharing and making all resources available to all researchers from within the country. It’s a concept of cooperation and collaboration which is convenient for funding agencies, and for the researchers themselves. This philosophy is a very good primer and very good way of attracting funding and human resources. Where do I see myself in this picture? I want to push these policies and systems which aim to amplify the distribution of resources so they can reach everyone- democratize microscopy. I love this principle, and I work in this way as a Head of Unit – I am always keen to support and help people, in a way that financial resources won’t be the main limitation for someone to address their scientific questions. I want to not only have this impact in my current institute (the Leloir Institute), but expand this philosophy to other institutes. I don’t want to keep it local nor be short-sighted. However, the financial issue of how (not) well paid science is, can be an actual problem – and perhaps an obstacle in these dreams. I find it shocking that many scientists (myself included) receive relatively low salaries and struggle to make ends meet at the end of the month. So it would be naïve to think that a balance shouldn’t exist. There has to be a balance. It raises the question on how long you keep pushing for these dreams, and how much stability you need for yourself and your family. It’s challenging, sadly.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Argentina a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

I love Argentina. I come from a family of Ukrainians, Moldovans and Italians. Now my children have my background as well as Polish, Basque, and native South-Americans (pueblos originarios). All mixtures are unique. It reminds me of a discussion I recently had with my eldest daughter, who asked me how many colours there are. It’s infinite. Argentina, like many places in Latin America, is super heterogeneous. In Buenos Aires this is very pronounced. I feel in Argentina we are citizens of the world. We also have a strong sense of belonging, like a brotherhood/sisterhood. It’s a very warm and open culture in Argentina. It’s not perfect, but these are some of its beautiful attributes.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)