An interview with Karina Palma

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 3 January 2023

MiniBio: Dr. Karina Palma is a postdoctoral researcher at LEO and SCIAN-Lab led by Miguel Concha and Steffen Härtel, at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Chile, where she works at the frontier of Biology, Physics and Computer Science, all linked by Live Microscopy. She graduated as Veterinarian from Universidad Mayor, and worked in her PhD between 2010 and 2015 with Miguel Concha as advisor in LEO.. Despite initially being interested in large animals, Karina found her passion for microbiology during her veterinary thesis, where she worked on bacteria in reptiles. Throughout her career, Karina has contributed to establishing novel microscopy methods in Chile, and one of her long-term aims is to contribute to democratizing science in Chile and making these resources equitably available across the country.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I was very curious as a child. I was always asking lots of questions. Even my mom says I was always asking “but why…?” Eventually after hundreds of questions, she would end up saying “Because that’s how it is! Because I’m your mom”. I come from Northern Chile, from a city called Iquique (all the way up north!). It has a great landscape, a beach, and also desert. In fact, that’s where the Atacama Desert begins. So I became very interested in the fact that although this desert is the most arid in the world, there is a lot of fauna, many oases and sources of water and life survives despite the extreme weather. I was curious about the adaptations of animals in the desert, to be able to live in this extreme weather. When I was little, I visited a zoo in Santiago, and I fell in love with biology and everything related to with animals. My love for cell biology and microbiology came a bit later. My first love was macro-biology, and I studied Veterinary Medicine because I wanted to work with large marine animals. Working for my degree, I realized that I actually liked scientific research more than clinical practice. Thus, from studying large animals, I switched gears and ended up focusing on developmental, cell biology and microbiology.

You have a career-long involvement in cell biology, image analysis and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose these paths?

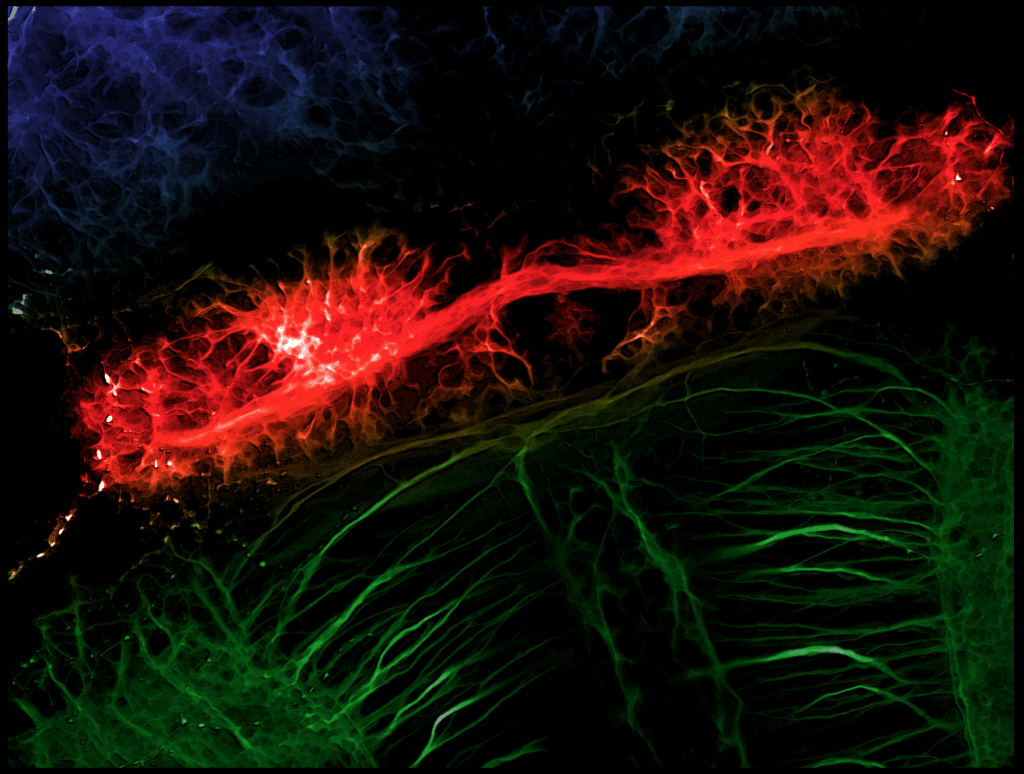

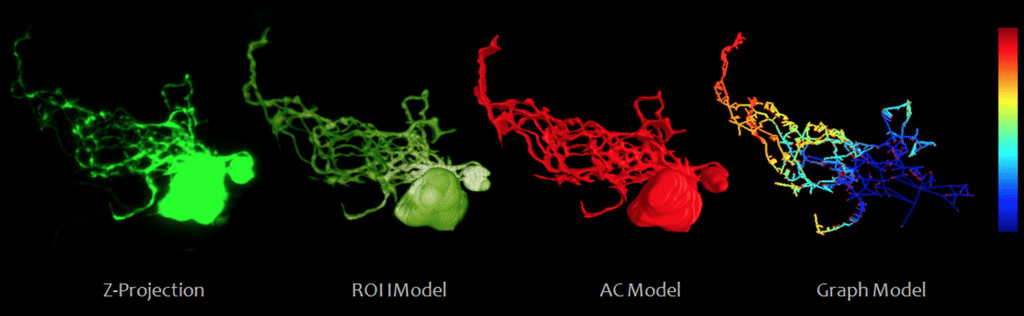

I became interested in cell biology towards the end of my degree, when I was writing my thesis, which focused on bacteria in reptiles. I learned PCR, Western blotting, and other molecular biology techniques, and I found them fascinating. I had learned about microorganisms early on in my career, but then I had changed focus towards clinical practice, so the microbiology side was out of my radar until my thesis. Since I worked on bacteria, I started using microscopy around this time too. After my degree, I enrolled on a MSc in Molecular and Cell Biology at the Faculty of Medicine, also in Chile. I realized I knew very little about the inner workings of a cell, and in this MSc I learned a lot! After this I did a PhD, and around this time I met Steffen Härtel, who had contributed to bringing new types of microscopy to Chile. I had access to spinning disc and confocal microscopes, and I found this technology extraordinary. Around this time, it crossed my mind that perhaps I shouldn’t have studied Veterinary Medicine, but rather Biotechnology or something that would be more relevant and would help me more in the field I chose to join for my PhD. I did my postdoctoral research in Chile as well, this time at SCIAN-Lab. During my PhD I went to Mendoza, Argentina, to study circadian rhythms with Dr. Estela Muñoz, where I focused on the effect of light on circadian rhythms. From here I started working on zebrafish –an animal model which allows you to study neurosciences, and how light influences the development of the nervous system–. With my team at LEO and SCIAN-Lab, we posed the question on whether a phenomenon we were observing, namely, neurons modifying their axonal projections during the day and night was (or not) directly linked to the circadian rhythm. In Mendoza I gained a lot of skills, especially on molecular methods, since my background was much more on microscopy. I also stayed for a brief period in Uruguay.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Chile, from your education years?

What was (and still is) an inspiration to me are all the scientists who do science here – not only in Chile but across Latin America. It’s difficult to do science here because resources are limited. So I found it inspiring to be taught by professors who put a lot of effort to do the science they do. The quality of science in Chile is really good, especially if one considers the limitations and challenges that we face as scientists. The questions that are raised, and the methods used to investigate those questions are innovative and original, and excellent despite the challenges. For me, to stay in Chile to develop my scientific career was a conscious decision. I want to contribute to the scientific and technological development of my country. I want to join the efforts to make it happen. I am passionate about what I do, and this is what keeps me going. To answer your question, I feel inspired by the scientists in the region. During my career, many people told me I should go abroad for a long period of time to be able to be a competitive and successful scientist, but for me, it was a conscious decision to stay here. Perhaps out of rebellion to prove everyone wrong and show that I could be a successful scientist while staying in Chile.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a postdoc in the SCIANLAB and the LEO?

I love being here because the topics the lab addresses require a multi-disciplinary approach. There’s a very strong component of imaging and image analysis, which I love. I had to learn a “new language” to be able to speak with physicists, mathematicians, engineers and computer scientists. I love this multi-disciplinarity. SCIAN-Lab/LEO are led by Steffen Härtel and Miguel Concha, a very renowned scientist in Chile. I did my PhD with Miguel as a supervisor, and my postdoc with Steffen. Miguel is a Biologist and Steffen is a Physicist, so as a lab, we had to develop a way to communicate successfully across disciplines. This new language we developed is more than the sum of both disciplines. I love microscopy, and I have realized that what you see in an image per se is only one part of the vast information that exists regarding a specific phenomenon. You can extract a lot of information from an image, and this is true for all biology. My day-to-day is very diverse. The lab is open to the whole country: we are part of the Biomedical Neuroscience Institute (BNI), and within it there is a subset of scientists called BioMat, who share resources and provide service within the country. So, we work together with many universities across the country. Scientists come to do microscopy – bright field, confocal, spinning disc, etc, – as well as image analysis, from segmentation to more advanced processes. I have a chance to work on topics as varied as fish, bacteria, and sub-cellular structures. It’s all very fun and keeps boredom away. It’s also very original and never monotonous. To be honest, I am a person that gets easily bored and what I love about my job is that it prevents me from falling into it. This depends on each person though – some people find this level of versatility in projects challenging or not ideal–. You have to be able to jump from one model to the next and one topic to the next several times a day. In addition, I’m engaged in teaching, so I also have to “change hats” through the day 🙂

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Chile?

It’s been great to collaborate with many different people both within and outside of Chile. The head of SCIAN-Lab, Steffen, is German, and he has strong links with scientists over there, so I have had the chance to collaborate with colleagues in Germany in Heidelberg and Bonn. – With them, we are working in light sheet microscopy and trying to achieve temporal super-resolution. With Miguel’s team at LEO, we worked with colleagues in Janelia Farm, as well as from Institut Curie and the CNRS-Sorbonne University, of the Integrative Biology of Marine Organisms-BIOM. Within Latin America, I was able to work with colleagues from Uruguay (IIBCE, with whom we have a close collaboration), Colombia and Argentina. We’ve had a great experience in this regard. I can’t think of specific challenges. The collaborations were very organic, and very productive. This has allowed student exchanges across countries, and very fruitful work.

As a Chilean scientist, did you have any challenges working abroad?

I think the language barrier is the most significant. I can’t express myself so naturally in English as I would like. The range of vocabulary to express myself is more limited. With respect to other things, it all depends on the lab you join and how rigid they are for certain things, which is also dictated by the type of work done in each lab: it’s different to work on Drosophila flies, than on zebrafish or cell cultures. But I guess this is true everywhere in the world.

Who are your scientific role models (both Chilean and foreign)?

In general, I have many role models – there are lots of people I find inspiring. Here in Chile I admire Dr. Cecilia Hidalgo: she won a National Science Prize, she’s one of the first to have worked on neuroscience, and the world-known squid model with giant axons. She found the ryanodine receptors which control calcium flux within neurons. She left Chile at a very young age, got married and had children, all during an extremely successfully and long career. She managed to handle everything, especially in a time when this was much more complicated for women. I find this extraordinary. She’s a very intelligent woman, but also very warm-hearted. I have met other bright scientists who don’t manage to mix both things. I have come across people whom you admire in paper for the work they do, but when you meet them in person you might find them arrogant, or simply not warm (or human at all!), and you can get disappointed. So in her case, she’s great – she’s a nice person and very generous with her time and knowledge. In Chile there’s an expression: “apañadora” – perhaps the closest word in English might be “supportive” –. I must say that Miguel Concha and Steffen Härtel are also very supportive.

Additionally, I find women scientists around the world inspiring. It’s a difficult profession if you’re a woman, and you need a lot of strength of character to do it.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Chile, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

Chile has been improving in this respect. For instance, for awarding grants for certain projects, committees now pay more attention at whether there are women as collaborators and team members, whether women in positions of leadership are included, and so on. But I think there is still a lot to be done. Egalitarian science and equitable science are not the same thing. Latin America is lagging behind in this regard. We need to pursue equity, which is something I hope we can achieve in the future. It involves a generational change! I feel that since, the young are trained by the older generations, especially in science, we need the scientists who are now young and have fresh ideas about gender equity, to become leaders and perpetuate this way of thinking and have an impact through generations. It should be a mission for everyone to change this spirit. In an ideal world this would result in more women occupying leadership positions, and more women winning Nobel prizes, and more women being role models for new generations of women. However, any efforts are valuable. Still, I find it difficult to be a woman scientist. It seems one still has to choose between having a family or having a career. I personally chose to have a family and have children, and this certainly made my career more difficult. My daughter was born during the 2nd year of my PhD – but I was lucky and privileged to count with my family’s support – my family and my partner gave me unconditional support and they understood the challenges. I feel I have achieved a lot, and I feel this is important also for one’s peace of mind and helps one think more clearly. So, I think one needs to find this balance between personal and professional. My feeling is that people who are unhappy personally, struggle more as scientists.

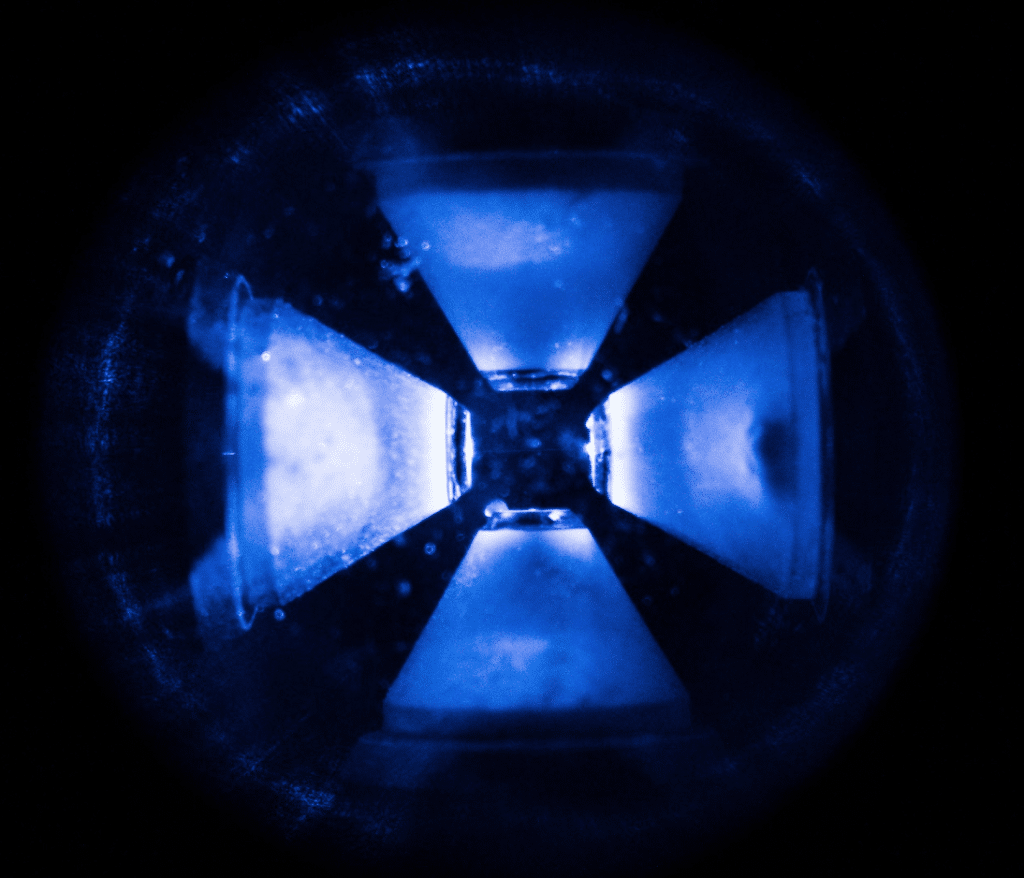

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

I don’t really have a favourite. I love all fluorescence microscopy. I also love electron microscopy, but it certainly requires much more patience for sample processing. It’s a very long protocol that requires a lot of precision. Equally, one requires a huge amount of expertise to cut samples – cutting at the microtome is an art. I don’t think I have enough patience for this, although I do love the results one achieves. I feel that most electron microscopists are very calm and patient people. If I had to choose, it would be fluorescence microscopy, also because the phenomenon of fluorescence is fascinating on its own. Within this ‘realm’ I don’t have a favorite type: light sheet, confocal, etc. are all fascinating.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

This is a great question and I’ve thought about it a lot. The truth is that the most extraordinary moment for me was when I saw a fluorescent cell. I turned on the light and I saw a green cell; it was an incomparable feeling. So every time I go to the microscope I am fascinated: even when I see something as simple as a Hoechst staining. I hope I never lose this capacity of wonder.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Chilean scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Never lose the capacity of wonder. I think this is the most important piece of advice I can give. You have to love learning and you have to allow yourself to be impressed. No experiment is “bad” – you’ll learn something new each time. Perhaps what you thought was wrong in an experiment, is simply a result you didn’t expect. Don’t get trapped in a loop of expecting a specific result and being disappointed with the results if they don’t match this expectation. Perhaps the ‘unexpected result’ is new biology you hadn’t even considered. My other piece of advice is to be perseverant: it’s one of the virtues one needs to cultivate. Most things won’t work out the first time around you try them, so you need to be resilient and perseverant. This applies to everything in the scientific career, from experiments to applying for PI positions – you might have to try many times.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Chile, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think the key to a successful scientific future is collaboration. In terms of microscopy I think an aim should be to make all the resources available to the entire country. Chile has a challenging geography: it’s a very long country, and it’s not so easy to reach every city or have a significant amount of resources available. Especially if one doesn’t know which resources are available and where, or what the expertise is. We need to make this all much more visible. We also need to increase resources in order to allow people from across the country to go to the various institutes where different microscopes are, or to invest those resources in acquiring equipment in a way such that it ensures their availability and access across the entire country. Perhaps an idea would be hubs in the different geographical regions, all the way from the North-most area, to the Austral zone. Another goal is that the reach of scientific knowledge should be extended: people in more isolated regions in the country do not always know all the possibilities of a specific microscopy platform, so outreach is very important, again, to ensure equity in accessibility – also in terms of know-how. I hope that one day we can do something similar to what the Advanced Microscopy Unit in Janelia Farm does: to be able to provide a service to any scientist that requests it.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Chile a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

The country’s geography is extremely rich in every way. For example if you are a bacteriologist, you can study extremophiles in the North of Chile with its extremes of heat, or extremophiles in the South in the Patagonia and the Antarctic, with extremes of cold. There are also extremes between the Andes and the Pacific Ocean. We have a huge amount of diversity in terms of fauna, flora, and environments to explore. It’s an amazing experience to travel across the country, despite the difficulties to reach the North or South extremes. So, we welcome all scientists to come and visit our country :)We’re always available to collaborate!

(1 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

(1 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)