An interview with José Luis Vázquez Noguera

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 7 February 2023

MiniBio: Dr. Jose Luis Vazquez is a researcher at Facultad Politecnica at Universidad Nacional de Asuncion in Paraguay. Between 2004 and 2008, he studied his undergraduate degree in Computer Systems Engineering at Instituto Tecnológico de León in México as an SRE scholar. Between 2009 and 2012 he completed his MSc degree as an Itaipú Binacional scholar. As part of his thesis, he implemented novel image processing methods for counting T. cruzi and Leishmania amastigotes. In 2018 he obtained his PhD degree in Computational Science as a CONACYT Paraguay scholar. He studied both, his MSc and PhD degrees at Facultad Politecnica, Universidad Nacional de Asuncion, under the supervision of Dr. Horacio Legal. He is a specialist in artificial vision and digital image processing and is amongst the first generation of students in the first postgraduate degree of this area, in the country. His lab focuses on generating novel algorithms for image analysis, and using machine learning for computer-based diagnosis. Most of his current work involves collaborations with clinical researchers, in the diagnosis of pathologies including retinopathies, infectious diseases, and dermatological diseases. He is also an associate professor at Universidad Americana, where he leads the lab for pattern recognition and machine learning.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

Actually I only discovered myself as a scientist during my MSc degree. Before that, my passion was Engineering, Mathematics and Physics. My degree was in Computer Systems Engineering. In my Masters I had the chance to participate in a workshop where a Spanish scientist taught us about microprocessors. It was then when I started to know what scientific research entailed: how to reach new knowledge, tackle problems that have not yet been solved, pose and answer questions following the scientific method, how to write a paper and communicate science and so on. I’ve always enjoyed challenges and tackling difficult problems. I think this is what motivated me to pursue the scientific career.

You have a career-long involvement in image analysis. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

When I studied my MSc degree, at Universidad Nacional de Asunción, there are various research lines one can choose from. At the time, the postgraduate degrees had just been founded, and one of the paths was digital image processing. When I took this subject I loved it – it required a lot of creativity and problem-solving skills. I feel that the foundations from my engineering degree were very solid and allowed me to choose this area. My MSc degree involved using microscopy images: basically, identifying and counting the intracellular parasite T. cruzi. Then I pursued my PhD and started teaching image analysis at an undergraduate level too. Then I felt really attracted to this area of image analysis. In terms of parasitology itself, the work I did was a collaboration with groups that are trying to find ways to tackle Chagas disease. It’s a neglected disease which affects all Latin American countries, from Mexico down, yet has relatively little financing. This group does lab tests with WT parasites – they didn’t want to generate transgenic reporter parasites, so manual quantification was challenging and time-consuming. Also, manual quantification is to some extent subjective and therefore error-prone. So I became involved in the project and the challenge was to generate a method for automatic quantification. Although I got to work with microscopists, my area is really computational science, and image analysis.

Regarding my career path, I did part of my studies in Mexico – I received a scholarship to work at Tecnológico de León, and then I returned to Paraguay. I then attended the workshop at Universidad Nacional de Asunción, which is one of the most prestigious universities in the country, and I met the coordinator of the MSc program – whom you have also interviewed (Dr. Horacio Legal). He invited me to do the MSc degree, and there were even funding opportunities via a scholarship. I had just finished my undergraduate degree and had no job at the time so this was a good option for me. I did my MSc and then PhD in the same lab.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Paraguay, from your education years?

I think Paraguay is still giving small steps when it comes to STEM disciplines. We’re just starting to develop these areas. Doing a MSc and PhD gave me lots of opportunities at an early stage, which perhaps in more developed countries wouldn’t have been possible. For instance, before I completed my PhD I was supervising undergraduate students. I already had to apply for funding, so I was able to participate in many projects. I was able to travel a lot – usually in other countries this chance only comes after the PhD, but I was able to travel to many places in Latin America even before defending my PhD, and elsewhere in the world too. Since there is no critical mass of scientists yet, there were lots of opportunities, and lots of challenges at the same time. This also gave me the chance to work in an interdisciplinary environment. Throughout my career, I’ve had the chance to work with medical doctors to help with diagnosis based on medical imaging, as well as biologists and scientists of other disciplines. There’s a lot of work, lots of things to be done, and very few of us – so there are lots of opportunities.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as an engineer and image processing expert at Universidad Nacional de Asuncion?

Part of my job is to supervise undergraduate and graduate (MSc and PhD) students. Writing projects and applying for funding is also a big part of the job. Our work is mostly funded by CONACYT Paraguay (which is the equivalent organization to CONACYT Mexico). Other activities include writing papers, traveling to conferences, presenting our work, teaching. Here in Paraguay most researchers also have teaching commitments, so this is part of the schedule too. Funding is a bit challenging here in Paraguay – it has improved a lot compared to previous years, but there’s no agenda when it comes to STEM disciplines. It’s difficult to predict when the different calls for fellowships will take place. In my case, my profile has helped me to also participate in calls for innovation-related projects (mostly attracting the commercial sector and enterprises). Since I belong to a National University, this also implies some challenges when it comes to obtaining funding. I’m also linked to a private institute – Universidad Americana, which has private and own funding. As an Associate researcher in this institute, this has allowed me to travel and to publish in journals which would otherwise be too expensive. Still, it’s a big challenge.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Paraguay?

I had a co-supervisor during my MSc and PhD, Jacques Facon, who is a French researcher, who was at the time working in Brazil. This allowed me to work in Brazil a few times. I also participated in the Conferencia Latinoamericana de Informática. It’s the most important conference in the region, for computer science, and each year the host country changes. I’ve submitted many abstract and presented many times in this conference. So because of my participation in this conference I’ve managed to visit many Latin American countries, and network with other groups. Currently I collaborate with another Paraguayan colleague who work at UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México). I did a short internship at UNAM over there last year in her lab. We had to be a bit creative to link our expertise – we use artificial intelligence, which I think is applicable to almost all research areas.

Who are your scientific role models (both Paraguayan and foreign)?

Here in Paraguay, Dr. Benjamin Baram, an emeritus professor at Universidad Nacional de Asuncion. He was also awarded the National Science Prize – he works in Artificial Intelligence, and has been awarded several international recognitions. He is the founder of the postgraduate program together with Prof. Horacio Legal. Regarding foreign role models, the founder of mathematical morphology – Jean Serra, a French scientist. He is the main reference in our area, and he has set the bar on what this area has achieved. Now there are entire centers dedicated to this area alone.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Paraguay, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

There can be no gender balance if there is no equitable access to knowledge – there is nothing legal or official here in Paraguay preventing women from studying whatever degree they wish, including all the STEM disciplines. However, there are other cultural or ideological barriers, so there are more men in the areas of Computer Science and Engineering. I have not had the opportunity to collaborate with many women scientists in my own country. Yet there are baby steps towards a change: for the first time in history here in Paraguay, the dean of the Polytechnical Faculty at Universidad Nacional de Asunción, where I work, is a woman. She has been key in promoting the involvement of women in science, and in breaking the glass ceiling, allowing women to reach leadership and decision-making positions, which was previously far less common.

What other barriers do you think exist in Paraguay preventing equity, aside of gender?

There is different access to opportunities depending on the area where one lives (eg. the capital city vs. other cities, or cities vs. rural areas in the country). Paraguay has now a program called BECAL (Beca Carlos Antonio Lopez, who is a former president of Paraguay). This scholarship provides funds for international exchanges, allowing Paraguayan students to go abroad for masters or doctoral degrees, with the commitment of coming back to Paraguay for a certain number of years. It requires a priori, the letter of acceptance from the foreign University. Sadly, the BECAL program is only very recent, and it didn’t exist when I was doing my PhD. Otherwise, I think I would have enjoyed it a lot. Regarding equitable access, for this program, the statistics show that most applicants are students from the capital city or the central region of Paraguay, and this is mostly related to the English language requirements. There is a language barrier of course. There are other differences between the rural areas and the capital city, but language is a main one. Not speaking English represents a major point of disadvantage, mostly for very capable scientists coming from other areas in Paraguay. To address this imbalance, to some extent, CONACYT has some new rules regarding the distribution of funds, depending on the geographical region of the institution where the applicant belongs. 30% of funds must be distributed to areas outside the central region of Paraguay. Hopefully, with time this will result in a better balance, and more equal opportunities across the entire country. Scientific outreach will also be key in the future, to reach a balance, not just to promote STEM disciplines country-wide, but also to better inform the general population about scientific activities being done in the country, who the researchers are, and giving more visibility to the work being done and its social impact. There is still an important gap between the general population and the scientific community. It’s important, especially in developing countries, to successfully convey the short and long-term importance of science to the general population. Otherwise, because our countries have many needs – and many basic needs are not covered, scientific research is seen as a luxury, rather than a priority. I feel a lot of this perception comes from a lack of understanding of the relevance of research and development to a country’s progress. So as scientists it’s our responsibility too, to convey the relevance of our work, and how it’s important for the country’s progress.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Paraguay?

We, Paraguayans, are very family-oriented! In Paraguay, a high percentage of people who do research or other types of work which provide the opportunity to work abroad, prefer to stay in Paraguay because of our strong links to the family. I have a strong bond with my family, and I missed them a lot when I had the chance to be abroad. To me, this was the biggest challenge. At the time, we didn’t have the technology to communicate in real time – we didn’t have WhatsApp or Zoom or any of the tools that now exist to “shorten” the distance. Besides this, we have different traditions and customs, which are difficult to replace abroad. For instance, here in Paraguay we drink tereré – while the Argentinians and Uruguayans traditionally drink mate, we drink tereré. The main difference is that the water is cold for tereré, while it’s hot for mate. Nowadays one can find shops almost anywhere in the world, to buy country-specific food or drinks, but it’s never the same. When I lived in Mexico, I managed to get hold of Argentinian herbs, probably due to it’s greater distribution (compared to the Paraguayan equivalent), but it’s not just the herbs. For example, in Paraguay we often drink our tereré together (in group), so this was difficult to replace abroad.

What is your favourite type of image processing/analysis and why?

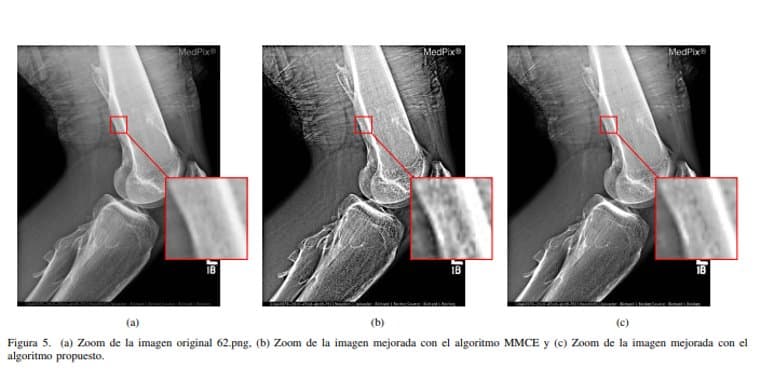

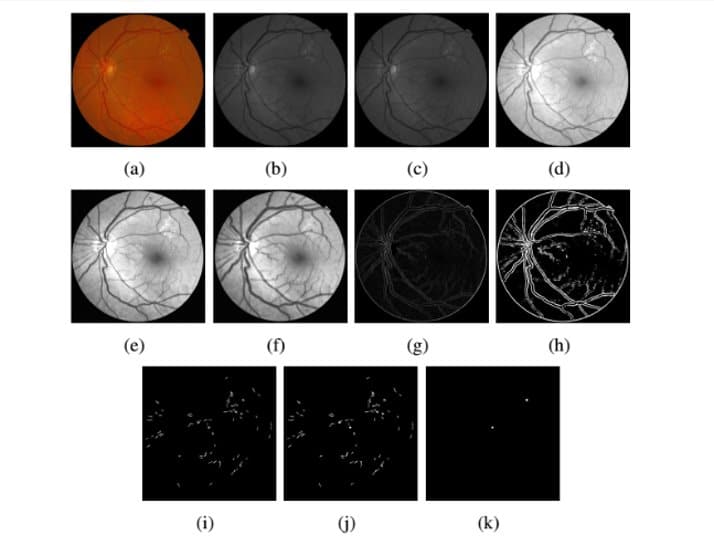

Most often, funding is preferentially directed to the medical area. So, for a while, I’ve been involved in projects involving medical imaging – doing automated image analysis to aid the physicians in the diagnosis. I currently work a lot with medical images, and I’ve enjoyed it a lot. It still comes with discipline-specific challenges – for instance, it involves a lot of collaborations with medical doctors, who use a completely different language to the one I use in my area. They have a different way of working too. Among the images I’ve analysed the three main types I’ve worked with are retinal images to diagnose retinopathies, histology images to diagnose parasites such as Toxoplasma, and images related to dermatology: through a dermatoscope, images are captured to be able to diagnose skin cancer, specifically, melanocytic lesions. Although these are the main types of images I’ve directly worked with, we also use image databases to test algorithms to improve, for instance, contrast.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy or the most extraordinary you have analysed as an image analyst? An eureka moment for you?

I think when you first see the results from algorithms for AI to do diagnostics, it feels like magic. Specifically, neural networks for deep learning are a bit of a black box – you don’t quite know what the machine is learning and whether what it’s learning are characteristics of features that medical doctors consider important for diagnosing a specific condition. But the results were really good! There was a bit of skepticism among the medical doctors on how good the algorithms would be, and even some fear on whether AI would replace them. I think it’s about team-work rather, but in general what I found surprising was how successful the algorithms can be in the medical area.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Paraguayan scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Study Mathematics! Also, programming is an ability that nowadays is pivotal in pretty much all areas of knowledge. You’ll need these abilities in the scientific career if it involves image analysis and microscopy. I would also say that the scientific career is something that will demand many hours of your life, and unlike other professions, you won’t see your efforts rewarded with high income. However, generating new knowledge is very satisfying and exciting, and to some extent can replace the other “issue”. I find that in Computer Science specifically, it’s very difficult to attract talent to the academic setting, because we are competing with big companies which offer much better salaries. In academia, we need to have excellent strategies for recruitment and talent retention, because the competition with industry is very disadvantageous. You really have to love the job as a scientist to choose this as a profession.

Perhaps this will promote better salaries for scientists altogether. In fact, the postgraduate programs have increased the salaries to the students, because the contracts require exclusivity, and with the salary that students used to receive it was challenging to make ends meet. Many students come from regions far from the capital, so they need to pay rent, among all other expenses. So, increasing the salary should be beneficial. But salary continues to be very low for scientists. It’s a pity really.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Paraguay, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think networking will continue to be crucial, and the crosstalk between areas (namely, academia, industry, AI, and software design) will be more important than ever. It’s already improving, so this will impact research as a whole, it will allow the automation of various processes as well as improve quality control. At present some methods of quality control (depending on the area of research) are still done visually and are subjective. This will likely change with the widespread use of automated processes and AI. With regards to how I want to contribute – currently I’m one of the few researchers with experience and a network that I have extended and continue to extend to my students. I’m very supportive of my students and I believe I’m also very approachable and ready to give a hand to talented students who are not under my supervision too. I think the BECAL program will continue to offer opportunities, and fellowships like this have a lot of potential at a country level. When there are enough resources, people will gravitate towards that area. I think there is a bright future ahead for Paraguay! ☺

Beyond science, what do you think makes Paraguay a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

From my point of view, what makes Paraguay special is its people. ☺ Paraguayans are very polite, and very welcoming to foreigners. I feel racism is not very prevalent in the country. We are very warm-hearted, and this makes the country a very special place to live.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)