An interview with Andrea Maldonado

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 14 February 2023

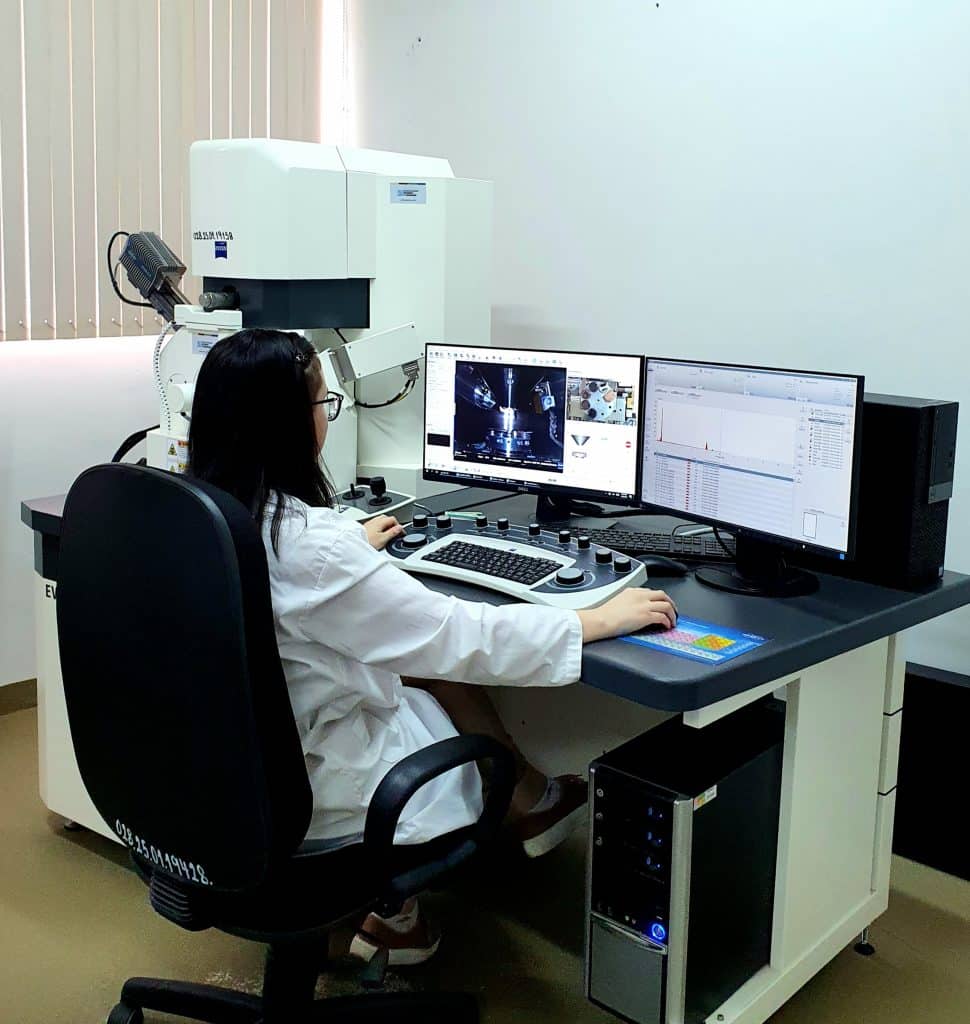

MiniBio: Andrea Maldonado is an Engineer in Material Sciences, and the SEM specialist at the Grupo de Investigación de Bio y Materiales (GBIOMAT) and the Lab of Bio y Materiales at Facultad Politécnica de la Universidad Nacional de Asunción, Paraguay. She did her undergraduate degree at the same university, and partly due to her interest in Modern Physics, she specialized in electron microscopy. She did her Masters degree in Education, with emphasis in University Teaching at Universidad Americana de Paraguay. She is the specialist in charge of the first scanning electron microscope in Paraguay.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

Since I was very young I was very interested in science (Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry), and I found these subjects relatively easy. When the time came to decide what I wanted to pursue as a degree in University, I had to recall what it was that I enjoyed studying most when I was younger. I was a very curious child – I would ask myself questions regarding the composition of things – why does a certain type of foam have a certain texture, and how does this relate to the material they’re made of, what’s their composition, and their physical characteristics. At Facultad Politécnica (of Universidad Nacional de Asunción) where I studied, a new degree was being created around that time – Engineering in Material Sciences, and that’s what was closest to what I was interested in. I looked in detail to all the degrees – I spent quite some time looking at all the possibilities, and the one that really “called me” was the degree in Material Sciences. Another thing that influenced my decision was that all my family works in the fields of Engineering or Education.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

Actually, when I started as an undergraduate I was 17 years old. I had little clue about the possibilities within the degree. Once I started my practicals and working in labs, I came to learn what an electron microscope is. Before this, I really didn’t know what it was or what it could do. But once I learned, I found it extremely interesting, and here I am 🙂 While doing my undergraduate degree, one of my professors made me aware that a scanning electron microscope was being acquired – the first in the country in 2019 – and I applied for the job as a microscopy specialist straight from the undergraduate degree. It was then that I started learning more about the physical bases and the operation of the actual equipment. Now there are 2 more SEM microscopes in Paraguay but they are not yet operational as far as I know. In terms of what we do, we offer services to the public – SEM can be used for different purposes, including material sciences of course. We usually give a consultation and advice to the researchers on whether the microscope will be useful for the purpose they wish to use it. It’s a huge range of areas. I’ve helped people doing work for odontology, biology, material science, construction, etc, We tend to prefer inorganic materials because sample handling is simpler when it comes to using the microscope. But if the sample is well prepared, one can do any type of analysis – there aren’t huge limitations.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Paraguay, from your education years?

I had very good teachers at University. I found it more inspiring to work in the area of material sciences when we started visiting factories – in Paraguay there are many factories for material production, creation and design. The teachers were very supportive, also because we were the first generation in this degree in Paraguay. The support we received from industry and academia was really good. Obviously there were some barriers, especially when entering a completely novel area which was previously not taught as a degree in Paraguay – few people knew what it was, starting with the family of course. In terms of the support I received, actually the job I got was due to the encouragement from one of my lecturers.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as an engineer at (Núcleo de Investigación y Desarrollo Tecnológico) NIDTEC at Universidad Nacional de Asuncion?

Generally, my work involves sample preparation and sample analysis for research groups –several skills come together to be able to perform compositional analyses on materials. Aside of this I always receive samples from students doing their graduate degrees, or research groups, or from private industry to help give insight in material fabrication. I also prepare quotes on costs for our work. That’s more or less what I do on my day to day. Luckily we’re always very busy! Because of the versatile nature of the work, I’m constantly learning new things. At the beginning this versatility made the job very challenging, but with years of practice, now I enjoy it very much.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Paraguay?

Not really. Foreign groups have given us samples or done their analyses in the lab, and this was all the contact I’ve had with Latin American groups. But I’ve never worked abroad or done internships abroad, or attended conferences or workshops abroad. Hopefully that will change, but for now, I can’t say I’ve collaborated a lot beyond Paraguay. I’m waiting for some funding I applied to, precisely for this purpose though 🙂

Who are your scientific role models (both Paraguayan and foreign)?

There is one professor whom I admire very much as a researcher – Magna Monteiro – she’s Brazilian and she came to Paraguay in 2011. From scratch created the BioMaterials lab- there was almost nothing when she arrived. Thanks to her dedication and perseverance, our labs are now much better equipped, and the infrastructure is much improved at Universidad Nacional de Asunción, which is a public institution. The infrastructure now allows for material synthesis, analysis, and increased research output- none of which was possible before.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Paraguay, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I think in general, in Paraguay, the gender disparity is very visible. Women representation is scarce in the professional environment, and women power even in the family is still scarce. Nowadays women are gaining more independence and demanding equal rights as citizens. Still, there is a long way to go. Personally, I went through several situations of gender discrimination. There aren’t many women in science, and the discouragement sometimes begins in the family: “how come you’ll study science, if you’re a woman”. For me it’s important to motivate girls, to tell them that they can achieve their dreams no matter what those are, and to eliminate the barriers I faced. One has to be strong to surpass those barriers that are not comfortable or easy for women. In this sense, a role model for me is my mum. She’s an engineer and a professor – since I was very young she always encouraged my dreams, and told me I should not limit my ambitions simply because I’m a women. She led by example – I found inspiration in her path. She never allowed external things to affect her path, and she gained the respect of her colleagues in due course. I’m lucky to have been raised in a family where I had her example and support. But this is not the rule in Paraguay – many girls don’t have an immediate role model like I did. There are organizations promoting girls’ and women’s participation in STEM disciplines, so this is likely to make a change eventually. I recently attended a talk for the inauguration of the “Capítulo Nacional de Paraguay de la Organización para las Mujeres en Ciencia para un Mundo en Desarrollo” – this is an organization for women in STEM disciplines, which facilitates funding and even provides scholarship opportunities to do internships abroad. This opens up possibilities for women, which I think is great, especially in a country like Paraguay where personal funding and country-wide funding is limited and in-country opportunities for training are also limited. I think this organization will play an important role in the country’s development in the coming years.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

SEM of course 🙂 When I started my undergraduate degree, one of the subjects I enjoyed most was modern physics including quantum physics. In these subjects, we studied the wave-particle duality. This included how in vacuum, electrons will behave like a wave. I became very curious about this. Later when we studied electron microscopy per se, we saw how the concept we had previously studied standalone, applied. I love how in science one can go from theory to practice very easily, and see in real life how things work, rather than reading the theory in a book. Electron microscopy also offers more possibilities than an optical microscopy. The nature of the interactions of electrons with the sample provides a lot of information. SEM is also very practical and relatively quick in yielding results. One can acquire a lot of information and characterize material very well. SEM is very user-friendly. It’s really my favourite for this reason.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

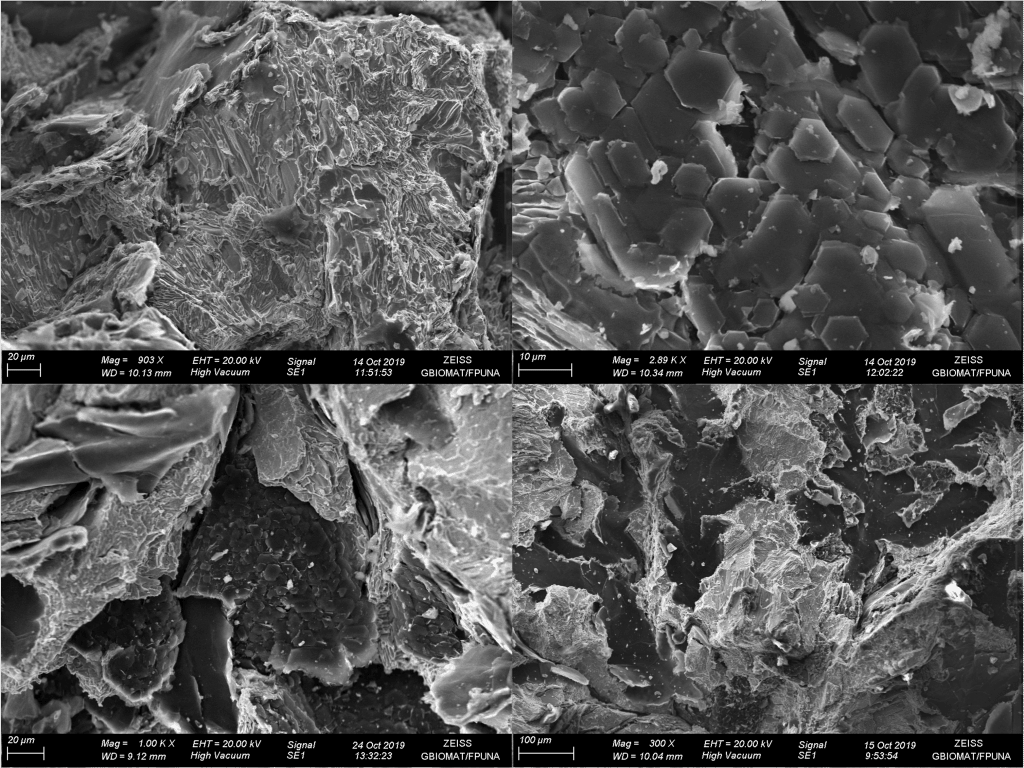

We got a sample which was part of a meteorite that fell in Paraguay. The collaborators who brought it thought that it had diamonds embedded in it. We did the analyses and it was really interesting to see the shape of the rock, how the layers were distributed: some layers were 100% iron, others were 100% carbon, some had a hexagonal form and one could see the transition between layers. I found it fascinating. It was one of the first analyses I did with the SEM equipment, so we could see its versatility and functionality in full display. We wrote a paper of this work in fact (Impact diamonds in an extravagant metal piece found in Paraguay). It made me realize how powerful the equipment is and how interesting it is to analyse different types of sample – one can acquire a huge amount of information with the SEM. I’m sure I’ll still see extraordinary things with this equipment so I’m very excited about the future 🙂

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Paraguayan scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Focus on your studies, and be perseverant. Usually as a student you’ll face situations where you’ll want to give up. Keep strong, don’t give up. You’ll need strength to overcome many barriers during your career. Later you’ll be able to choose your specialization. If this specialization is microscopy, I would suggest you dedicate some time to studying abroad. I have taught some students here, but it’s complex because I have not completed my training due to lack of funds, so it’s important to learn from people with lots of expertise. I motivate my students to work hard and dedicate themselves to their studies. Eventually you’ll be rewarded, and your effort will pay off. Motivated students are incredibly valuable to the scientific community. Research and education are amongst the basic factors for the improvement and development of a country.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Paraguay, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I see there are other groups in Paraguay, acquiring more equipment and developing areas such as image analysis – I hope a collaborative community will arise which will facilitate knowledge exchange. I hope this will result in a positive feedback loop: more funding for the acquisition of equipment, more equipment that allows more research to take place, and so on. This will prevent a brain drain or a dependence whereby we need to go to other countries to do our analyses because we don’t have the infrastructure at home.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Paraguay a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

It’s a beautiful country. The people are very kind, very open and very welcoming to foreigners who are interested in learning about our country. It might be a developing country, but it has lots to offer. Come to Paraguay and share your cultural and scientific experience. There’s many people in Paraguay who have never travelled abroad, so it’s always interesting to see other perspectives of the world. The landscapes are beautiful, and the food is amazing too.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)