An interview with Leslie Tejeda

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 21 February 2023

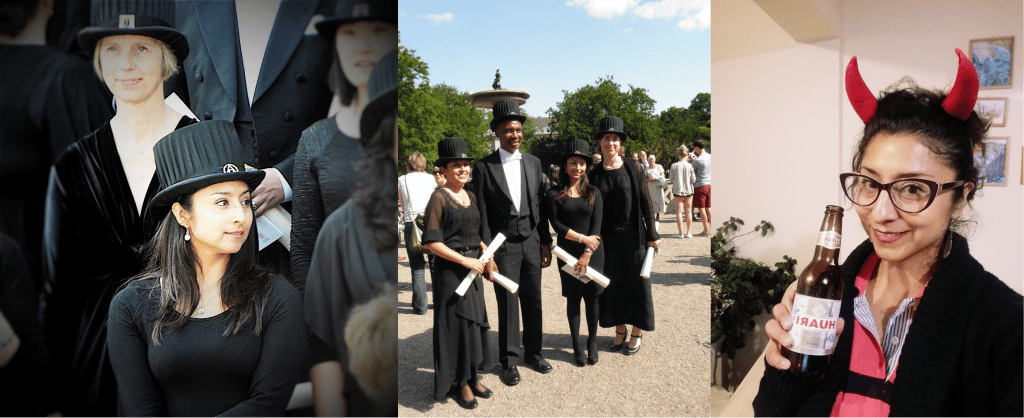

MiniBio: Dr. Leslie Tejeda is a profesor and part-time researcher at Universidad Mayor de San Andres, in La Paz, Bolivia. She completed her undergraduate degree in Chemistry in Bolivia, and was later awarded a fellowship under the ASDI program which promotes international collaboration for sustainable development (ASDI), to go to Sweden to do her PhD. She did her PhD in La Paz, Bolivia, and Lund, Sweden, under the supervision of Prof. Björn Bergenståhl and Lars Nilsson between the years 2008-2013. During this time she specialized in Food Chemistry. Since going back to Bolivia, Leslie has been part of several organizations, including Swebol Biotech, SI Alumni Network Bolivia and TWAS, where she focuses on the generation of sustainable food, and on the scientific development of Bolivia.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

During secondary school already, we made an aptitude test to see whether we were more inclined to the social or the exact sciences. The test showed I was more apt for the social sciences, but I was not convinced. I knew those tests are helpful for orientation rather than a definitive answer. I knew exact sciences is what I wanted to pursue. My brother is actually a Systems Engineer and he has always been very supportive and has given me some guidance when it comes to the career. Once I left school, since he was aware I loved Physics, Chemistry and Mathematics, he suggested I take a look at a degree offered in the same faculty where he studied – the degree of Chemistry. He told me that Chemistry has a vast range of applications and specialties: environmental, textiles, food, pharmaceutical, etc. They were really many options, and I found this career very attractive. We were 500 applicants to the faculty of exact sciences, but the faculty offered several options. About 30 of those 500 applicants were aiming for the degree of Chemistry, and only 2 were selected – I was one of them. Chemistry at the time was a relatively small class here in La Paz, Bolivia. I studied at Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (UMSA) – it’s a public University, and the main university in Bolivia. In the last 4 years a poll has shown that it’s the highest ranking University in the country. In Latin America it must be in position 128th place. Anyway, only 2 students were selected for Chemistry and I took this as a confirmation for myself, that I was on the right track, in pursuing the degree I had chosen. The degree offered a lot of opportunities: we had access to fellowships, we often had external speakers from Bolivia and from abroad – at the time, the faculty of Chemical sciences had strong collaborations with Sweden, France, Japan, etc. I liked this very much: there was always lots of interactions with people from abroad.

You have a career-long involvement food chemistry and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose these paths?

When I studied, the Bachelors degree in Chemistry was 5 years long. Four of those years were core subjects, and in the fifth year you get to choose a specialty. In the 4th year one gets to study applied Chemistry to the different areas: organic chemistry, inorganic chemistry, phytochemistry, food science, etc. Around this time I realized I found chemistry applied to food science (especially food transformation), fascinating. That’s when I decided to join the specialty of Food Chemistry. I then applied for a fellowship. I was already working with Swedish collaborators, under the ASDI (Agencia del Desarrollo Internacional) program – which is an inter-country agreement (between Bolivia and Sweden) that aims to promote cooperation for sustainable development. During the interview, the Swedish professors determined which graduates would be suitable candidates for working abroad. After being selected, I went to do my PhD in Food Chemistry in Lund, a small city in the south of Sweden. It’s pretty much a University City. My PhD lasted 5 years, but the idea of the program is to promote knowledge and infrastructure exchange between both countries, so the PhD involved me being both in Bolivia, and in Sweden. During this time I was able to purchase equipment, and establish techniques in Bolivia. Dr. Mauricio Peñarrieta was my professor and later we became colleagues. Around the time when I was a student, the infrastructure of the Chemistry labs was very basic – a “skeleton” only. Just the 4th floor was fully completed, but not the rest of the building. There was very little in terms of infrastructure. The building where the degree of Chemical Sciences was taught only had one floor fully finished, with labs that had mostly outdated equipment – the rest of the building was just the structure, or “skeleton”. The institute made it a priority to finish this building, and the collaboration with Sweden was very helpful in this respect, and in obtaining state-of-the-art equipment for the labs, as well as improving the syllabus for the degree. I think this collaborative program has been very successful and specific to science, it has allowed the creation of new research lines altogether, and it has strengthened our institution.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about working as a researcher in Bolivia, from your education years?

When I started my PhD I was very afraid that I wouldn’t “reach the bar” of the European system, but I realized that the education level was really good. My biggest challenge was the language, but not the science. Language was an issue because in most middle-class schools in urban areas of Bolivia, English was not well taught or not taught at all. In many very expensive private schools, English was well taught, but this is not the rule amongst most private or public Bolivian schools. I attended a “middle-class” school. The school has strong cooperation for development, with Germany – so I found the cultural adaptation in Sweden (which I find similar to the German style in terms of pace and discipline), relatively easy.

When I finished my undergraduate degree I realized the importance of learning English, so I enrolled in an accelerated course to learn the basics. Once I was in Sweden, I learned English better out of need of course 🙂 I’m not an expert yet, but I can survive.

Can you tell us a bit about your day to day as a researcher at UMSA?

I’m now a professor – not yet full time though. There are only few institutions in Bolivia where one can do research. Many institutes don’t have well-equipped labs, and science is really much more theoretical than practical. The UMSA is more serious about research, so our labs are now well-equipped, and there are various exchange programs in place promoting visits from/to various countries. This is not the case of many private (or public) institutes. However, it’s very difficult to be admitted to UMSA. In 2013, we were 5 PhD graduates (all female) who applied to become PIs at UMSA. Out of all 5, I’m the only one who was eventually admitted. My other colleagues became tired with the admission process: initially, we received 3-monthly contracts only, then 6-monthly – we were lucky if we got a 1-year contract. My colleagues eventually found more stable jobs in industry or as teachers in secondary schools. At the time, I couldn’t understand why such talented researchers would end up not pursuing the “researcher” path, but they definitely have better paid jobs, with much more stability. I still think you are limited as a researcher on how much you can do if you’re not in a University that values this work. So it’s a trade-off. What I found unfair though, is that some time later, when many male graduates applied for positions, they were all accepted without all the fuss, tests, and hoops that we (the women) had to go through. If we analyse the statistics, recent studies showed that the proportion of male and female professors is 76% vs 24%. There’s a huge gender gap in our Faculty of Natural and Pure Science. In other faculties, like the Faculty of pharmacy and biochemistry (51 % M, 49 %F), this gender imbalance is not as wide. I think this has to do with the fact that most of the people in decision-making positions in Bolivia, are men. Since, two years ago, the Vice-rector of the University is a woman from a science background– something that doesn’t happen very often. We – the women in sciences – had high expectations about the change she would bring about, because she was previously a vice-dean of science. But I haven’t seen many of those expected changes so I reckon the system is difficult to change, even from within and from positions of power, more work is needed regarding gender equality and collaborations among women.

Could you tell us a bit about your role at Swebol Biotech, and your inspiration to belong there?

Swebol Biotech is a spinoff company that was founded in 2015 by Dr. Mauricio Peñarrieta, Dr. Patricia Molinedo and Dr. Enzo Aliaga together with various Swedish researchers, like Professor Olof Olsson and Olof Böök. It’s the first spinoff within an institution – it was ‘born’ from a collaboration with a Swedish company called Aventure AB. Aventure AB is a food company, whose aim is to generate advanced and clinically verified products, concepts, and processes in functional food and biotechnology. In 2016, they started developing a formula to develop a quinoa-based vegetable beverage. Around this time, I was struggling to join UMSA as a professor, but I was developing techniques to dehydrate food, and was very familiar with the spray dryer – one of those technologies. I received an offer to collaborate to dehydrate this beverage. In Bolivia, we don’t have access to technology such as Tetra Pak for instance, which would enable longer preservation of foods, in this case, in the liquid state. That’s the reason we wanted to be able to store this beverage in its dry form. As a result of this collaboration, I was able to join the team. The beverage was patented at an international level, and they wanted to patent also the various ways of preserving it, including dehydration. I’ve been a member of Swebol since. In 2017 we managed to develop the infrastructure – a factory – to produce the dried product at a larger scale. Sadly due to a lack of technology and resources, the factory was functional for 3 months, then out of service for 1 month whenever any part of the equipment was damaged. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, we decided to close the factory because it was not affordable anymore. In 2018 we went to Bogota, Colombia, to seek collaboration, to see whether they would be able to produce the liquid product, but they hadn’t had lots of experience with vegetable milk. I think in general, in Latin America, we don’t have well-established technology or expertise in this respect. Most industries in the region have lots of expertise with milk-derived products, but perhaps not so much on alternative products.

Can you tell us about MathAmSud and your work on Chemical Graph Theory?

In 2017, I, together with several PhDs (all young women), founded the SI Alumni network Bolivia. The purpose of this network was to bring together all the former fellows from various areas of knowledge and expertise. In 2018 as vice president of the SI Alumni Network Bolivia during my visit to Stockholm, Anna Lindhagen, (who was the Programme Manager of the Swedish Institute Management Program – SIMP) and I got in contact and she explained the program’s success in other countries. One year later she came to Bolivia and she started the SIMP program, which trained around 90 people in issues related to innovation, business sustainability, and its connection to the global economy. Definitely, this network opened the door to other networks, including the TWAS (The World Academy of Science) network, where I am more active, and the MathAmSud whose focus is mostly Mathematics. I’ve collaborated with them, and the idea is to do applied Mathematics in the area of Chemistry. I’ve participated in seminars, and we have done some “baby steps”, but we haven’t managed to get something very solid out of the collaboration. But we’re still working on it. Still, I’ve managed to be very active in several networks.

Have you had many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Bolivia?

In the last few years, since 2017 when I started getting involved with several networks, I’ve had a chance to interact with more Latin American groups. I feel that after I came back from Sweden to settle in Bolivia, I gradually lost contacts with my Swedish collaborators. I find this very sad, because I think research benefits from international collaboration and international perspectives. It’s through the networks that I’m starting again to have an international outreach. So far I’ve collaborated with Swedish, French, Colombian, and Costa-Rican colleagues. At present, I’m the coordinator of a summer course – done through the TWAS network, which aims to foster collaboration between Bolivian and other Latin American researchers. This will include organizing workshops, postgraduate courses, etc. to promote scientific development in the region. This coming March we will have participants from Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica and Ecuador. They will teach several postgraduate level courses in the areas of Physics, Chemistry and Biology. If it succeeds, we hope to repeat it on a yearly basis.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Bolivia?

At the beginning, soon after my arrival in Sweden, it was very tough. I come from a middle class family and in Bolivia, the average middle-class person can rarely travel abroad. One usually goes somewhere within the country for holidays. So the very first time I left my country was when I went to do my PhD in Sweden, which is not even close-by to allow weekend visits to the family and friends. It was a long trip in every way. Also, I needed to face a new culture, a new language, everything new. After facing these initial language barrier comes the challenge of facing a big world: it was very international place, so I had the chance to meet lots of people from different backgrounds and cultures. For me the experience was wonderful altogether, but at some points it was very very difficult. I was also much younger and it took me a while to understand how the different world I was suddenly facing, worked.

Who are your scientific role models (both Bolivian and foreign)?

Within my institute, there is a very admirable researcher – Dr. Monica Moraes – she’s the one who invited me to become part of the TWAS network. She’s the director of the National Academy of Sciences in Bolivia, and she is a woman. I have realized with the years, that the role of women in science is much tougher, especially in academia, so I find her career and her work admirable. Also, women’s participation in Swedish society in different fields, is also very admirable. I’m a mother of two girls, and although sometimes I felt like switching to a different job because of the difficulties of academic life, I realized it was important for me on one hand not to give up on my own dreams and on the other hand, to change the landscape for future generations of women (which includes my daughters). My wish, and what I want to work towards, is that women’s participation in science is no longer silenced. There are still many cultural and generational biases affecting science in Bolivia. For example, sometimes if a woman expresses a bright idea, it’s ignored, but if a man validates the idea, it suddenly becomes important. I’ve faced this particular situation many times.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Bolivia, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I think there’s A LOT to be done to reach gender equity in Bolivia. Every day you watch the news in Bolivia, you’ll hear about women being raped or killed. The least protected people in Bolivian society are women and children. According to the UN organism CEPAL, statistically, in South America, Bolivia is the first place in violence against women, and the first place in feminicides. So this already shows you what the position of women is in this society. This imbalance permeates to, and is very visible in academia. I have suffered several gender-based discrimination and abuses in my career, and for this reason I try to include women in networks and activities organized in academia. Swebol has this policy too – to promote gender balance and to promote and normalize women in positions of power.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

The interesting thing about microscopy is that it allows us to explore an infinite community of microorganisms. In the area of food chemistry, when you’re processing or designing food, you must think not only about the macro-world, but also the micro-world. The product must be innocuous, as well as healthy. This is what I find extraordinary in the process of food microbial chemistry, and microscopy allows us to take a peek into this world.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Bolivian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopy?

Bolivia needs new researchers. Bolivia is a hyper-diverse and pluri-cultural country, and there’s lots to be done. We have lots of natural resources, and we need this force: young researchers who inject energy to the current research community, who contribute not only with their knowledge, but with their dreams and hopes. It’s tough to be a researcher here, but don’t give up – it’s worth it if it means we are together building a better future.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Bolivia, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

In Bolivia, 14 years ago a political party called MAS (Movimiento al Socialismo) took power, under the direction of a controversial political figure – president Evo Morales. In the first few years of his government, a lot was done for the benefit of the country: there were no highways, no schools in isolated areas, etc. Since I have been at UMSA for many years – first as a student and later as a researcher – I’ve had the chance to travel around the country for the purpose of work. That’s why I noticed these changes, starting with better interconnections within the country’s urban areas, and between them and the rural areas. I’ve seen a transformation in those initial years. But of course, 14 years in power brings about other issues – not all of them positive. The current government is still pushing for the industrialization of the country, and I support this dream. I think everyone’s energy is required to make this happen, especially when it comes to efforts devoted to science, technology and innovation. I feel I’m contributing from within academia, by training the new generation of scientists, and motivating them. Many people go on to do postgraduate degrees abroad and never return to Bolivia. I encourage young people to return, to not lose faith, and to help us make Bolivia a better place together.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Bolivia a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

It’s a beautiful country and you’ll fall in love with it easily. Its biodiversity is huge, as is its range of landscapes. I’m from the Andes region, but for example, even La Paz has the two landscape extremes: within just a few hours you can go from the Andes region to the Amazonian region. I have traveled abroad, and while I found other countries very appealing, it’s not the same. The biodiversity and landscapes in Latin America are something rather unique. I have friends from Europe who wouldn’t understand when I told them that I missed the landscapes in my country. Eventually, when they visited, they realized what I meant and what makes my country special. I think it’s safe to say the same is true of many countries in Latin America.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)