An interview with Natalia Montellano

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 4 April 2023

MiniBio: Dr. Natalia Montellano is the director of the degree of Biotechnology Engineering at Universidad Catolica Boliviana San Pablo. She is also the current Chair of the Bolivian Chapter of OWSD (Organization of Women in Science in Developing countries). She studied her undergraduate and PhD degrees in Argentina, and was awarded an OWSD-UNESCO fellowship for her work. Her expertise is protein biophysics as applied to food science. Her work does not only involve research, but she is also heavily involved in scientific outreach and science communication. She has belonged to the Sciences Clubs Bolivia and various other groups aiming to close access gaps to STEM disciplines. In terms of microscopy, she has used imaging to study protein-protein interactions, protein aggregates, and protein structure throughout her career. Equally, in collaboration with scientists in California, she is involved in a project involving cloud-controlled microscopy, which aims to provide equal access to microscopy technologies, to students in Latin America.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I was always a very curious child. People often think that my parents are scientists because me and my brother are scientists. He is a physicist. But my parents are not academics. My mom is a stay-at-home mom, and my dad is a Chemical Engineer, but he worked in industry all his life. However, since me and my brother were always very curious, my parents were always very supportive. They didn’t limit us. Instead, they rather encouraged us to satisfy that curiosity. Since 2000, we had a computer with Internet. In the past there were atlases, very common in Latin America – our parents bought these for us. Perhaps when it came to toys they were more restrictive, but when it came to learning material, they were always very supportive. I knew I wanted to be a scientist only when I had to choose a degree. Before this, I didn’t really think about it. Whenever I was curious about something, I could go about and explore so I hadn’t thought about it as a degree or as a profession. I feel that in Bolivia we don’t really have close role model scientists – it seems something very far away, something foreign and distant from our reality. The closest profession one might consider is to become a medical doctor. The last 4 years of high school I chose a track where you have a lot of Chemistry, Mathematics, Physics, Biology. I enjoyed those classes. I don’t think the teachers were great, and I say this because many young students at that stage feel frustrated with the classes if the teaching is not very good, and they feel they should not pursue a scientific career, based on their experience with their teachers. I would like to encourage them not to think this way – regardless of whether the teachers are good or not, if you like science, you can pursue it as a career. One year before leaving high school, my father told me about the career of Biotechnology, which had all the scientific disciplines (Chemistry, Physics, Biology, Mathematics). When I googled about it, I thought it was a very well-rounded career, with all the disciplines, and I found it interesting. I didn’t want to give up any of the scientific disciplines – in fact this was one of the reasons why I didn’t study Medicine – I didn’t want to give up studying Mathematics or Physics. So that’s how I ended up studying Biotechnology 🙂

You have a career-long involvement in biotechnology, protein science and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

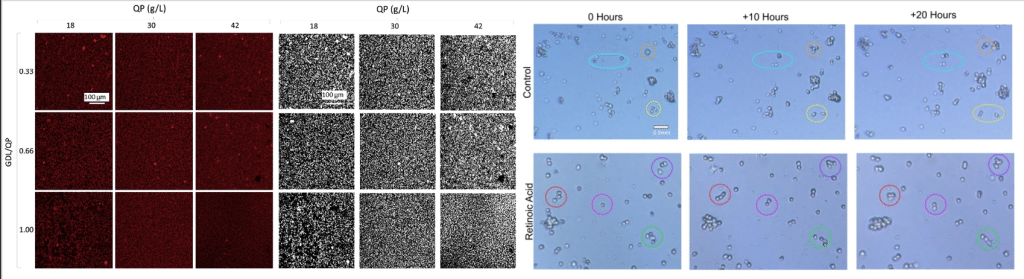

I studied my undergraduate degree at Universidad Nacional de Rosario in Argentina, and was later funded by CONYCET to do my PhD in the same university. At the time, the degree of Biotechnology was not taught in Bolivia. The first few years of Biotechnology were a bit boring because they taught all the basics of all the sciences. In the 3rd year I did really bad in the subject of Physical Chemistry, but because I did so poorly, I doubled my efforts. In the 4th year I applied to become a teaching assistant on this subject. So I joined this discipline. As an assistant, I realized that many undergraduate students were doing research internships already. Since I was living alone in Argentina, I wanted to occupy my time to the fullest, so as not to feel alone. So in addition to being a teaching assistant, I applied to become a research assistant as an intern too. The group I joined focused on the physical-chemical properties of proteins. During my undergraduate degree, the focus of the Biotechnology degree was not only on genomics, but the product – proteins, both from the technical part, and the basic research importance: what they do within a cell, how they interact with one another, their structure, the effects of overexpression or abrogation of proteins, and so on. My project as an intern involved studying an enzyme with catalytic activity on pollutant poly-cyclical proteins – this was in the field of bioremediation. While I started this project as an intern, I continued with it as my undergraduate thesis project. Later on, after many years, for my PhD, I entered the field of food biotechnology. Since I’m Bolivian, my PhD supervisor suggested that we could study the proteins of quinoa. I found out some work had been done on quinoa in Australia and Ireland, but not much done regarding proteins in flour. So, we extracted proteins, and we studied their physical-chemical properties, as well as the production of quinoa gels (similar to tofu). This involved studying their structure, using microscopy. We always used microscopy to investigate how proteins interact with one another. The technique I used most was confocal microscopy. Once we had elucidated the electrostatic interactions by microscopy, we started opening new research avenues within the same research line. For instance, how protein aggregates occur, or the structure of different enzymes during the process of cheese-making. Since we were also studying aggregates, we did confocal microscopy to figure out the arrangement of protein arrays in soluble and gel forms, with different pH. We did mathematical modeling to see what the different arrays depended on and how proteins arrange themselves, both in soluble forms and in gel. That’s all in my last paper from my PhD. Regarding my involvement in cloud-controlled microscopy, this is more directed towards education. The project was born from the need to use technology during the COVID-19 pandemic, or do research remotely. The project started in California in 2020, when most of the world was in strict confinement. The creators of the project designed a system of microscopes that could use cameras and sensors to obtain images whenever necessary- they started studying neurological stem cells. That’s how this project was born, focusing on the needs of researchers in California, but then the project was expanded to allow scientists in Latin America to get involved with this technology remotely. So far it involves not only Bolivia but also Colombia, and several other countries. The idea is that students do real scientific experiments, and that they can follow up their experiments through the images they acquire. We tried to adapt the platform so we could also acquire videos, but the resolution and image quality was very poor. So the images are assembled in the cloud and the students can follow up the progress of their own experiments. Everything in the paper was the students’ idea. This project has allowed us to interact a lot. For instance, within the context of this project, the students in Latin America have received training on image analysis, starting with what to look for in the images to make hypotheses or reach conclusions. They produced a lab report on what they had learned, and we did a poll which we included in the paper.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Bolivia, from your education years?

We are very few scientists in Bolivia, so there are lots of opportunities for people to enter various fields. This allows you to open many fields. At Universidad Católica, where I’m currently working, I’m opening many research lines. I won an UNESCO grant some time ago, to study local fruits that no one else studies, because those fruits are native to Bolivia. There’s a possibility to study many things specific to the region (in Latin America in this case), for example, extremophile bacteria living in temperature extremes or in the salt flats, or biodiversity specific to the Andes or the Amazonia. So while perhaps other countries might have a longer history with scientific research, or better resources, we have a vast field of scientific questions to be addressed due to our geographical location, with little competition. The scientific career is not oversaturated as in other countries.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a researcher at Universidad Católica Boliviana?

My role at the University is at the moment administrative – I am the director of undergraduate studies, and dedicate half of my day or more to this role. There are pros and cons of this role: on one hand I have limited time to do research, on the other hand, I can have an impact in what is taught and how, in the undergraduate degrees. I teach Chemistry also, so I have teaching duties. And I do research too, and have supervisor duties as well. I am also the Chair of OWSD Bolivia chapter.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Bolivia?

During my PhD I started collaborating with other researchers in the region. I also did a research project in Brazil, in the field of Biophysics. One of the teachers, Prof. Fernando Barroso, does both Physics and Biology. He does computational simulations. I told him I was having trouble with my experiments – the interaction curves I was obtaining for quinoa proteins did not make sense to me. I expected them to be the other way around, relative to what I was obtaining. So I discussed these results with him and he told me that electrostatic interactions could be studied by computational simulations. I learned how to do these simulations, to be able to explain my wet-lab results. I went to USP in Riberão Preto, to learn this technique, and this eventually went into one of the papers I published during my PhD. In the lab, we also worked close together with groups in Brazil and Argentina to complete the food production stage. We didn’t have the infrastructure in my university to scale up food production. Now that I returned to Bolivia, it’s necessary for me to collaborate – at present for instance I’m working on a project to detect viruses in residual water, a cooperation with a Bioscience private laboratory and UMSA, a public university from La Paz, in collaboration with Costa Rica also in the big picture of the project. Another collaboration is is with Californian and Colombian universities with the picroscope project. I think one thing that has helped my collaborations is that in addition to science, I love science communication. I was a member of Club de Ciencias Bolivia, and Club de Ciencias Colombia. I taught a course in Colombia for two years, and I got to meet students over there with whom I continue to collaborate.

Who are your scientific role models (both Bolivian and foreign)?

There are various Argentinian researchers from Universidad de Buenos Aires, whom I’ve loved working with. Nowadays I’m working with Pilar Buera, on a project focusing on circular economy. The collaboration focuses on science communication. We organize conferences once a year, and have a database of people working on similar topics in Latin America. She’s one of my role models because in the area of food science ans technology she is a main reference in Argentina. She’s a super nice person, very humble and very collaborative. She’s always willing to help. In Bolivia, at UMSA I met Dr. Maria Teresa Alvarez. She’s Bolivian. She studied abroad, but came back to Bolivia, and she’s one of the most successful scientists at UMSA in the branch of Biotechnology. She has done research spin-offs. Sadly, no enterprises have been founded as a result – I feel as scientists we lack training as businesspeople, but we are currently trying to do something together.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Bolivia, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

In the Chair of the Bolivian Chapter of OWSD (Organization of Women in Science in the Developing World), which belongs to UNESCO. I got a UNESCO grant in 2019, and when I went to Italy to receive this grant, they told me about the Chapters, and how their purpose is to incentivize women and girls to pursue STEM disciplines. Since I was already involved in Clubes de Ciencia. I contacted the former Chairs, and started reaching out to other women who also belong to this chapter. In 2021 we submitted the application and we got accepted. We started working on scientific outreach projects. I do a lot of networking under this project too- but one has to reach out and be very courageous to get projects running. I feel there is a huge difference in terms of gender balance between Argentina and Bolivia. In Argentina a lot of the group leaders where I worked, and even faculty members, were women. Indeed, the scientists at the very top of the ‘ladder’ were mostly men, but there was female representation at other levels. In Bolivia, I feel we are one generation behind. The majority of people in all leadership positions are men. I remember the first meeting I attended as a lecturer in the Department of Exact Sciences, where we were 25 people in total, but only 3 of us were women, and one of them was the cleaning lady. This difference was huge. I think what we sometimes lack is the audacity, rather than the capacity, to be in leadership roles.

Are there any historical events in Bolivia that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

I don’t recall any specific event that has had a huge impact on research. One thing I do notice plays a major role in the scientific landscape, are international cooperations. In 2000, the Swedish cooperation joined public education in Bolivia, and they have trained a huge amount of people at various levels – masters and doctorate and post-doctorate degrees. Many people have stayed abroad, but the ones that have come back have made a huge difference in the country’s scientific landscape. I’m at Catolica, but when I go to UMSA or Universidad de San Simon, I notice the effects of this international cooperation. And it’s not only Sweden, but also France and Spain, who have had a huge influence in Bolivia.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Bolivia?

I spent 11 years in Argentina – one has to take some things with humour. I remember when, for example, I would get a taxi, the taxi-driver would ask me about my accent, and where I was from. I would say “I’m Bolivian” and they would always say “you don’t look Bolivian”. Also, although we are in Latin America and we share a lot of culture, food, language, and traditions, we are still different countries with very unique things. People were very supportive. I think what was also a shock, was the transition from being a ”child” to becoming a working adult who has joined the workforce abroad, and has to pay taxes in a different country, and figure out how everything works in a country that is not your own. Still, it’s possible. Perhaps the biggest challenge is wondering whether or not one can fully blend in to the new society. For instance, I didn’t manage, and came back to Bolivia a few days after defending my PhD. In Argentina they have a complex system, and fierce competition for positions. There are people who end up getting used to it – for example my brother did his PhD in Germany and stayed there to live, he did not want to be an academic. I am happy though, to have come back to my country, and to be able to contribute to its research workforce. In 2018, when I came back, I sent postdoc applications to various European countries, but while I was doing this, the call for Director of Biotechnology opened, and I applied. I went to the interview, and was told in December of that same year that I got the position.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

Confocal microscopy 🙂 it allowed me to link wet-lab with mathematical equations to better understand proteins.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

In a lab practical – I can’t remember if during my PhD or the last year of my undergraduate degree – we used zebrafish with fluorescent hybridization markers. It was fascinating.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Bolivian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Study a lot and put a lot of effort on your work. I think there is no hidden trick to succeed in this career other than that. I always tell this to my students – it’s not an easy career. You have to understand the physical and chemical processes that result in the biology/biochemistry we study. This is true for any biological discipline: bacteria, fungi, viruses, etc.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Bolivia, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I wish we could have a science system like the one already well established in other countries of the region, such as CONICET (in Argentina), or CONACYT (in Mexico), where you have projects that are supported by the government, and which the government recognizes as important for the country’s development. This is my dream for the future of science in Bolivia. Microscopy, in Biotechnology, is super important, and has an immense amount of applications. Now that I am working with plants, we use microscopy to do the morphological characterization of fruits, in addition to the in vitro characterization. We want to know what the compound structure is. I want Bolivia to have a better microscopy infrastructure, including both electron and optical microscopes. So I hope we can invest more on this aspect in coming years.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Bolivia a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

Since Bolivia is a small country, there are lots of opportunities. There is space for you, you have lots of resources at your disposal, for example in terms of food biotechnology, there are lots of unique food sources here: fruits, plants, meat, etc. You can do a lot with little money – which is the opposite situation if you go to expensive countries in the global North. We have a very rich culture – I only realized this when I went abroad. There are many cultures within the same country. It’s also a beautiful country – so I encourage everyone to visit 🙂

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)