An interview with Estefania Quenta

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 18 April 2023

MiniBio: Dr. Estefania Quenta is research associate to the Institute of Ecology at Universidad Mayor de San Andres, Bolivia, and member of the Organization of Women in Science for the Developing World. She has worked as a consultant for the UNEP, and participant in a training program of IPCC (the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Estefania did her undergraduate degree in Environmental Engineering at Escuela Militar de Ingenieria in La Paz, Bolivia. She later studied her MSc in Ecology and Conservation at Universidad Mayor de San Andres- it was at this time that she discovered her passion for water research in the context of climate change. Later on, she was granted with an ERASMUS MUNDUS SUD-UE grant to do her PhD at the University of Tours in France. A lot of her work has focused on investigating the effects of glacial retreat on wetlands in Bolivia. She used microscopy during her career. You can read more about her at https://estefaniaquenta.weebly.com

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I think there are many things that inspired me to become a scientist. It wasn’t a single event. At school there wasn’t a strong scientific culture, so once I finished, I had to make a choice regarding my career. I felt I was rather good at Mathematics and at Biology so I decided to study Environmental Engineering. In my family there are no scientists, but my father wanted to become an Electrical Engineer, so when I told him I wanted to study Environmental Engineering, he gave me his unconditional support. If I have to choose and event in particular, it was the first time that I read a scientific article that showed me the application of many topics we had studied during our courses and this was a turning point.

You have a career-long involvement in environmental engineering, ecology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

Once I finished studying environmental engineering, I had the big picture of the discipline, and a sensation that I needed to deepen my knowledge on something specific, and this was when the call for the MSc in Ecology and Conservation with an 84% scholarship came out. I got the scholarship through a competition process, and after finishing my Master courses I joined a project on high-Andean wetlands (bofedales – humedales altoandinos) in Bolivia. It was huge project. The research team wanted to understand the impact of glacial retreat wetlands, and I had the chance to work on the aquatic part of this project. Data collected during the project helped me to do my MSc and PhD research. For my PhD, I was awarded an Erasmus Mundus -SUD-UE grant for the University of Tours, in France.

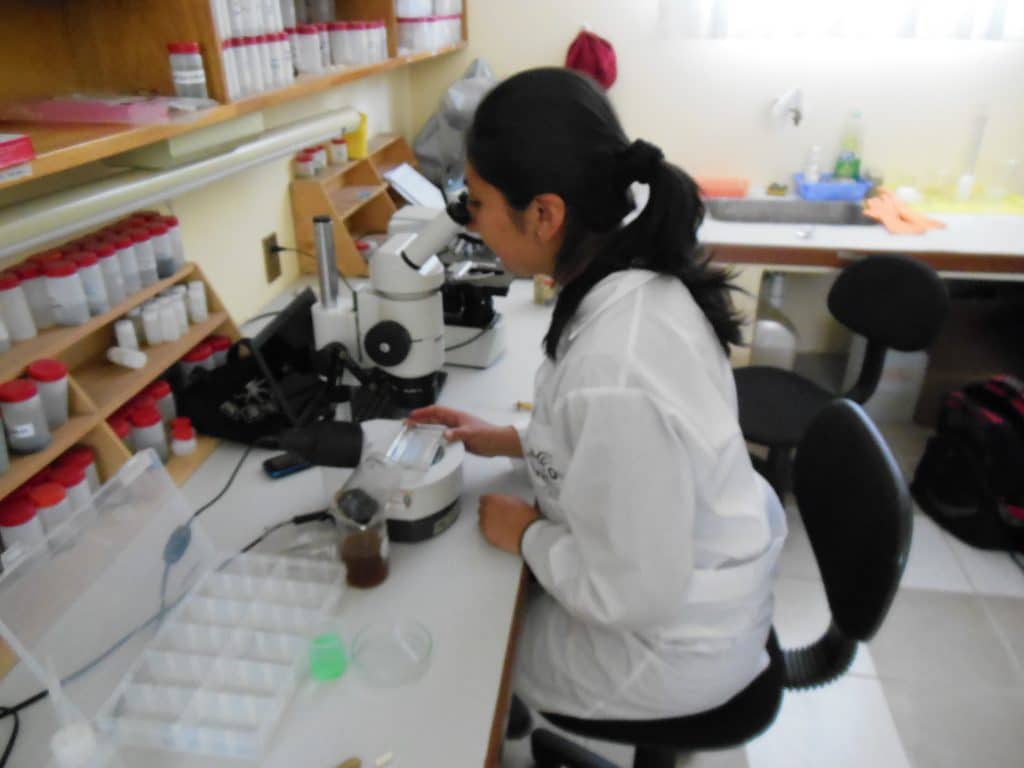

Microscopy was an essential tool to analyze the aquatic samples I collected, and my main motivation is contributing to the knowledge on freshwater ecosystems, and in dong so, contribute to their conservation. The samples include everything: clay, soil, organic matter, etc. So, before analysis, one has to clean the sample very well under the stereoscope. One can spend hours cleaning the sample before the actual analysis, so I found that microscopy required many hours of work, and a lot of discipline.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Bolivia, from your education years?

I would say that the feeling that I am contributing to freshwater conservation efforts, and to the scientific culture of my country, which is not strong in comparison to other countries, are very rewarding experiences.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day at the Institute of Ecology at Universidad Mayor de San Andres?

I don’t yet have my own group. Nevertheless, since my PhD I had the opportunity to be the lead-author of several articles. I would say that it was a very rewarding experience because I learned a lot during the publication process. I also had the chance to teach at the department of Biology.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Bolivia?

Yes, I actually did. I had the opportunity to be in touch with scientists from Ecuador during the writing of scientific articles and also, I served as field work assistant on a project regarding glacier streams in the Antinsana and Carihuairazu mountains.

Who are your scientific role models (both Bolivian and foreign)?

I admire all Bolivian scientists who do research, in particular the young scientists. We face immense challenges to be able to do research. So, I think already being a scientist (anywhere in the world) requires a lot of bravery. You need to be brave to pursue a career where experiments might or might not work, there are a lot of question marks all the way from hypothesis formation to paper-writing.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Bolivia, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

Yes, I feel that I was affected by gender issues, but mainly for being young because it’s still uncommon for people to get a PhD at a young age in Bolivia, so I needed to work even harder to show that I am capable to do things. However, I can’t generalize as there were some people (older than me) who supported me. I believe that initiatives like the OWSD from UNESCO are really important to highlight the profile of women scientists in Bolivia. Currently there are 178 OWSD Bolivian members, which shows that I am not the only one woman in my country who intends to peruse a scientific career.

Are there any historical events in Bolivia that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

I can’t think of a specific historical event that could have impacted the research landscape of my country, but what I can say is that if the government decides to strongly support Bolivian scientists and universities, this could produce a big change in our scientific culture. This is something I witnessed happened in Ecuador, for example.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Bolivia?

Yes, I did at the beginning. Specially because of the language. However, I was able to overcome it. Now I feel capable and able to communicate my thoughts in international conferences.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

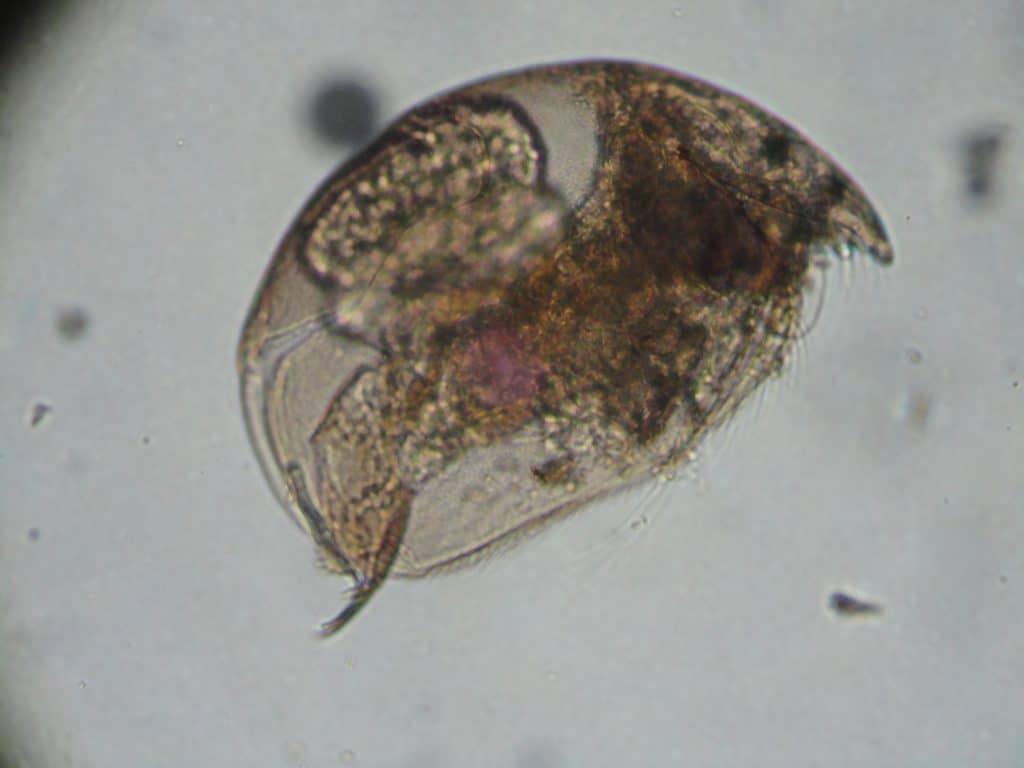

I would not say that I have a favorite type of microscope. I used a stereoscope and an optical microscope that helps us to identify aquatic organisms at the maximum level of organization, such as family, genus and species; and following taxonomic keys. So, this equipment was the minimum for our main task in the lab that basically consists in understanding how changes in the aquatic environment can impact on the aquatic biota.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

Seeing hidden insects is already an exciting thing. I got excited when I was able to identify some aquatic organisms at the level of species, some of them endemics to the Andes.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Bolivian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

You have to be perseverant. The path as a scientist is not easy at all. So, I would recommend that those who genuinely want to be scientists, work with a lot of discipline and passion, and don’t give up at the first difficulty.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Bolivia, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I’ve seen how capable my students have been when I had the chance to teach at Universities. Seeing this amount of potential in the next generation makes me feel very positive about the future. I believe that if I aimed to pursue the scientific career despite of the difficulties, the next generation who takes this step, will certainly achieve many things.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Bolivia a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

We have a huge variety of ecosystems, all the way from the Andes to the Amazonia. Salar de Uyuni (Uyuni Salt Flat) is something magical to behold. The diversity of food is also huge – there’s something for all tastes. My favorite is Charque – it’s fried dry meat, with corn and potatoes, and a spicy sauce. I really recommend this! 🙂 and in general, Bolivian food.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)