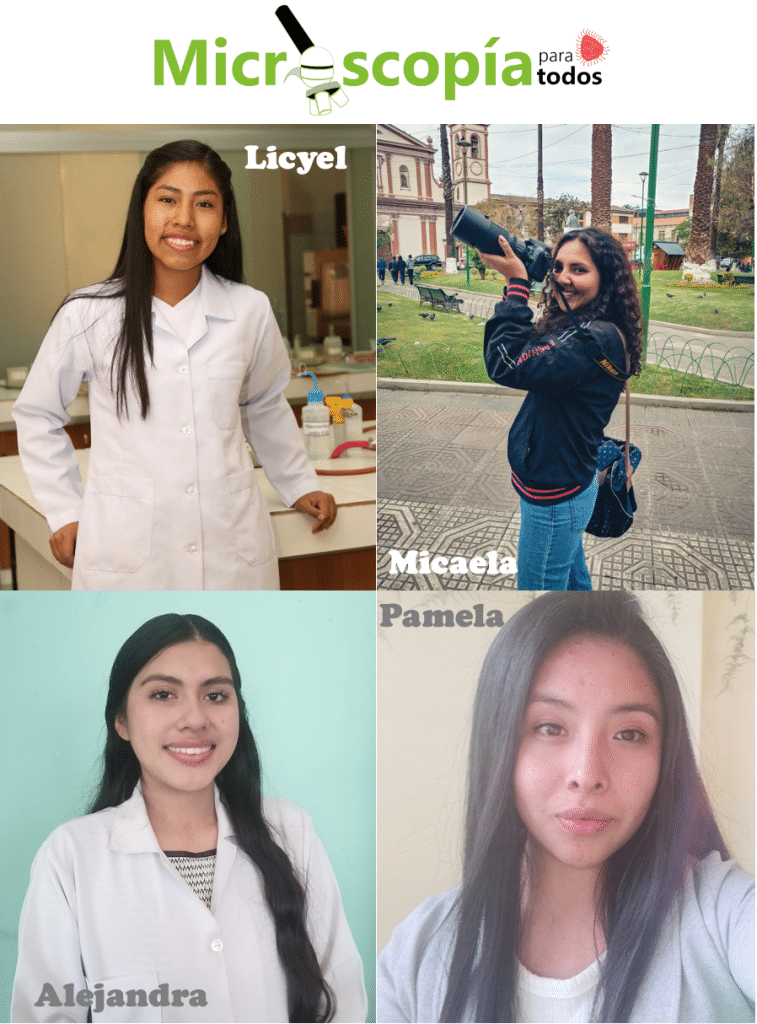

An interview with Microscopía Para Todos leaders: Licyel Paulas, Micaela Mendieta, Pamela Perez, Alejandra Guzman

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 25 April 2023

MiniBios:

Licyel Lenny Paulas Condori is a master’s student in the Interuniversity Molecular Biology Program organized by Vrije Universiteit Brussels, KU Leuven, and Universiteit Antwerpen (Belgium). She has a Bachelor’s Degree in Biology from Universidad Mayor de San Simón where she graduated with academic excellence. She has been awarded different scholarships and grants from the United States Embassy. She is co-founder and National Director of Social Impact at Microscopia Para Todos (2018), an organization that promotes STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics). Licyel is the former president (2018 – 2019) of the Scientific Society of Biology Students and has worked as a teaching and research assistant of different research centers and courses. She was the first Bolivian intern (2018) at the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and the first Bolivian representative at the 61st London International Youth Science Forum (2019). Licyel was selected as one of the 100 Young Leaders in Biotechnology in Latin America (2021). Recently, she has been recognized by the Plurinational Assembly Brigade of Cochabamba and the Chamber of Senators of the Bolivian Plurinational State for her valuable contribution to biological sciences and for being an example for the Bolivian youth.

Micaela Mendieta Ortiz is completing her bachelor’s degree in Biology at the Universidad Mayor de San Simón (UMSS) in Cochabamba-Bolivia. She also holds a diploma in Higher Education Based on Competencies from UMSS. Micaela provided services to the Autonomous Municipal Government of Cochabamba (GAMC) in the area of Wildlife Trafficking. She was part of the Research and Conservation Program of the Bolivian dolphin as well as part of the Citizen Ambassadors Program Agenda 2030-2020. Micaela is a former scholarship holder of the Centro Boliviano Americano CBA- Embassy of the United States with the Central Park scholarship and was one of the National Coordinators and Co-founders of Microscopia Para Todos.

Alejandra Guzmán Jaldin is a Biology bachelor student at the Universidad Mayor de San Simón, in Cochabamba, Bolivia. She was president of the Scientific Society of Biology Students (SOCEB). She currently is a student research assistant at the Biotechnology Center-UMSS, where she works with extremophile microorganisms from the Uyuni Salt flat. Alejandra was part of the volunteering team in Social Impact and Communications at Microscopia Para Todos. She is a co-departmental director at Nos Gusta la Ciencia and a volunteer at iGEM Bolivia. She is a scholarship holder of programs such as 360 Effect Women and Tech, Tu Beca Bolivia, World Tech, Bolivian Asteroid Search Campaign, Semillero Científico Be Tech, Science Club International, and Conecta Mentora.

Pamela Perez Vallejos is completing her bachelor’s degree in Industrial Engineering at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (UMSA), La Paz, Bolivia. She obtained international collaboration for the advancement of the consumer characterization project in the supply chains of La Paz-Bolivia, to develop her thesis. She has also specialized in operations management and data science, with a focus on supply chain and logistics. Currently, she works as a researcher in the UMSA and is part of Microscopia Para Todos and AIESEC LA PAZ.

Can you tell us a bit about what is Microscopia Para Todos? What inspired this project?

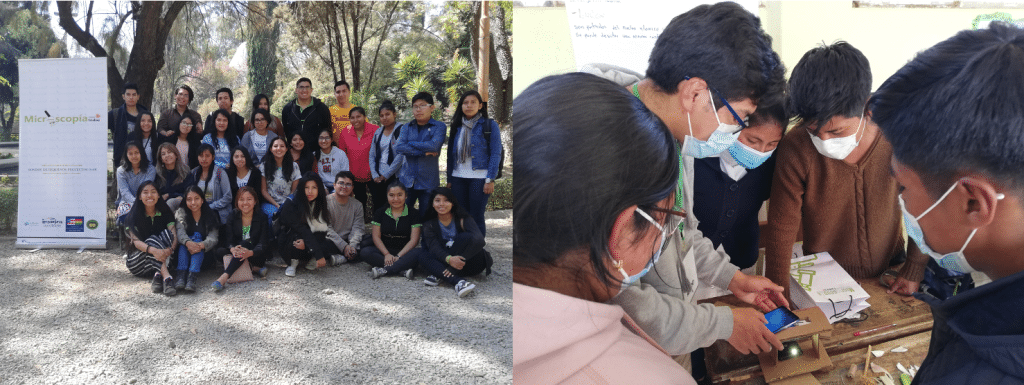

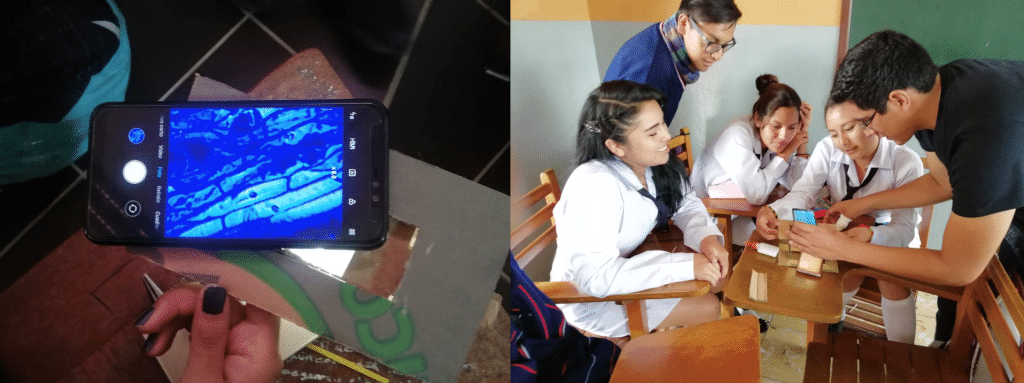

Licyel: The idea came from two sources – I studied in a public secondary school where we didn’t have microscopes or even a lab where to perform experiments. At the time there were external 5-day workshops, called Clubes de Ciencia Bolivia, organized by Bolivian and also foreign people, to teach basic experimental lab skills. In one of those workshops I had the chance to build a microscope made of wood and glass, and a lens from a laser pointer. I was in awe. It was an inspiration for Microscopia Para Todos because I wanted to be able to bring something similar to schools like mine by using only cardboard and a laser pointer. Also, when I joined University as an undergraduate, it was the first time I learned how to use a microscope, and I noticed that students coming from private schools already had much more experience, which becomes a source of inequality. So I spoke with Micaela (Mica) and Pablo (members of the Microscopia para Todos team) and I shared with them the idea of bringing this type of workshops to their former schools and mine, to see how the kids would like it. At the time we were undergraduate students of the BSc of Biology, and we did this as a social service project as part of the degree. Moreover we wanted to promote the degree of Biology, since we were very few students in comparison with other degrees. In exchange, we asked the University to provide material such as glass, methylene blue, and other reagents that might be harder to acquire. One of our professors, Erika Fernandez, became a mentor for our team. In 2018, during the first year of the project, we began by visiting my former school and Mica’s and a few other schools. We noticed that the kids were super enthusiastic and very excited with the workshops, while others were more interested in learning more about scholarships, about specific careers, or even how to apply to university. We decided that for 2019, in addition to focusing on the didactics of microscope design, we would also incorporate talks about Bolivian success stories in science, STEM degrees, scholarship opportunities, application and admission to university degrees, or applying to fellowships/scholarships to study abroad or for international exchanges. We noticed there was an issue that it’s not lack of talent stopping many students from taking advantage of great opportunities, but rather lack of information. That’s how Microscopia Para Todos really started – later on more people joined and the project grew a lot – it now includes several cities in Bolivia, and hundreds of members and participants. The project and all our workshops are mostly aimed at students from junior high school and high school.

Micaela: Indeed, students from as early as 2nd year of high school and even younger have taken part in the project. We’ve also designed workshops for children as young as 8 years old. They were super fascinated with the activities.

Licyel: Our pilot tests included children too, but at that point we were still deciding which age group to direct the workshops at – for instance, we noticed that children find the workshops very exciting but they still lack some basic information to enjoy the full extent of the activity – for instance many don’t yet know what a cell is, because they haven’t studied the theory at school yet. Also, to work with children we have to seek permission with the parents, so it all becomes stricter than with slightly older students. Moreover, students in junior high school are closer to having to make the decision of which university and career to choose. So we wanted the impact of the workshops to be greater. We wanted to show the students that they have options beyond conventional careers such as Medicine or Law.

What impact has this project had at a community and at a country level?

Micaela: One of the project’s original aims was to incentivize young people to join the degree of Biology. We (myself and other members of Microscopia Para Todos) are still in University, to we are very close to the experience that the new students are having. We have noticed that the number of applicants to the Biology degree (and other STEM degrees) has increased substantially. We want to think that the MPT project had some influence in this. However, we haven’t conducted a systematic and thorough study to determine what the exact impact of the workshops and MPT has been.

Licyel: It’s difficult to separate the influence of MPT on later STEM involvement by participants of the workshops. Also, we started this project soon before the COVID-19 pandemic. We don’t know if the pandemic itself also motivated young people to join the Biology degree to become researchers. One of the ways in which we have quantified the impact of the project is before and after each workshop we carried out polls. These polls have evolved with the years – in the first year we didn’t do any poll because the project was still at a pilot phase. Afterwards, we did polls at the end of the workshops, where the participants had the opportunity to suggest what to improve, what else to include and do during the workshop. What we consistently saw as a result was that more women were interested in STEM disciplines than men. We didn’t know how to monitor this interest between the moment of the workshop and these student cohort’s entry to university – to see whether this inclination towards STEM disciplines remained. In subsequent years, our polls were designed together with psychology students, who helped us optimize some aspects of the poll. With their help we were able to measure not just interest but also perception- for instance, how young students in junior high school and high school perceive scientists and science as a profession. It was very interesting to do: we were able to get an idea of the impact not only of the hands-on part of the workshop on building microscopes, but also about the talks on career choice. Perhaps Alejandra, who has been a speaker in these talks, can tell you more about this aspect.

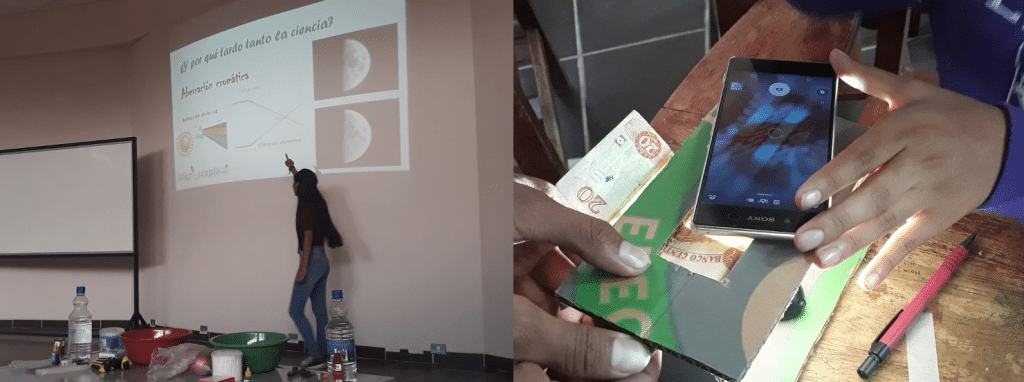

Alejandra: The dynamic of the workshops was really interesting. The workshops are divided into two parts: an introduction to microscopy: what it is, how microscopes work, the physical basis of microscopy, etc. and then the practical part: building home-made microscopes with off-the-shelf materials. The students would observe anything, from common objects such as coins to sophisticated samples such as onion cells and cells from the mouth mucosa. For many students this was something new and interesting. One could notice their enthusiasm and engagement, and their wish to learn more about the topic. In the other section of the workshop, we gave talks on STEAM disciplines (including arts), which was more motivational for the young students. It has been very gratifying for me as a volunteer to see that the information we have provided through our workshops has been useful! As Mica was saying, it might be that our MPT workshop did influence the student’s decision on joining STEM disciplines.

I noticed the project targets various communities. Can you expand on this topic further?

Licyel: Our target community was always students in public schools within cities in Bolivia. But as we traveled to rural areas, we noticed even greater inequalities. And we realized that the impact of the MPT workshops was even greater. So we have also targeted public schools in rural areas. A main issue so far has been the COVID-19 pandemic: as we were expanding the project around the 4 main cities (La Paz, Cochabamba, Santa Cruz and Chuquisaca), the pandemic struck, so we shifted our work to online mode. The fact that internet access in rural areas is sometimes restricted or even non-existent was prohibitive for this aim. After the COVID-19-related restrictions decreased, we went to a small town in La Paz, thanks to a volunteer who organized a visit to one of the schools.

What are the project’s short, middle and long-term aims?

Licyel: One of the main limitations we have faced is the lack of funding. Since we don’t have constant and stable financing, one of the challenges is to find funding. One of our short-term aims is to apply to grants that provide funding to maintain and expand the project. We also wish to keep working together with younger generations of scientists, volunteers and students. For example, some of our former volunteers have held or will hold certain leadership roles within MPT. Other participants like Mica, Pame and myself are now in the process of searching for jobs, or starting postgraduate degrees, and so our involvement in MPT is becoming trickier and trickier. I also find it crucial to pass on the leadership of the project to younger generations, who have potential and fresh ideas – it’s an evolving project that requires evolving leadership too, rather than any form of stagnation. We have also worked on making the workshops more efficient – we have realized that when we take up too many hours from the classes at the schools where we deliver the workshops, we get complaints from the teachers and parents – although never from the students. So we keep the workshops to a maximum of 3 hours. I’d like to give a more definitive answer, but until we get a stable source of funding, it’s tricky to make long-term, complex, plans.

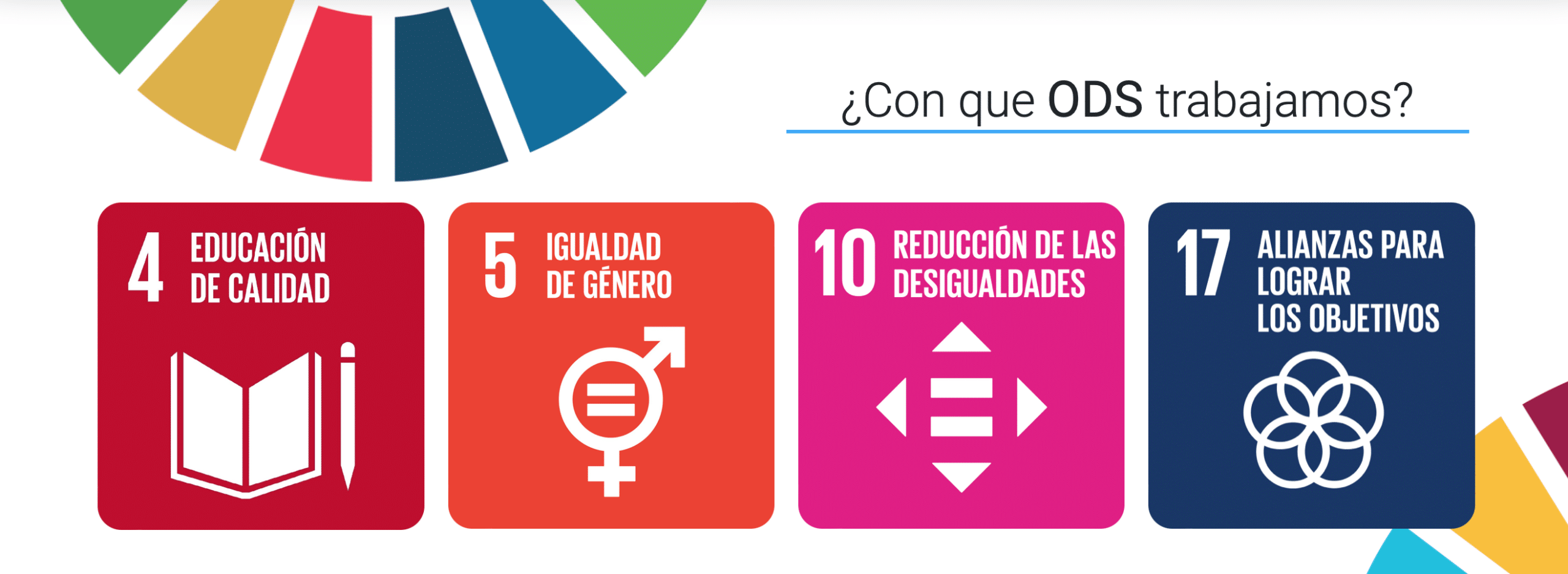

One of the highlights of Microscopia Para Todos is that it addresses sustainable development goals 4 (quality education), 5 (gender equity), 10 (reducing inequalities), and 17 (alliances) – can you expand also on how Microscopia Para Todos does this, what it has achieved, and what it hopes to achieve in the short, medium and long-term future?

Licyel: we aim to reach students of all backgrounds in rural and urban areas of Bolivia. Also, we know that some disciplines have a huge gender disparity, including unequal access to the careers altogether. So, in our workshops and talks we started emphasizing the work not only of Bolivian scientists in general, but also Bolivian women in science. We spoke not only about degrees, but also about opportunities. For example, we spoke about specific organizations where women played key roles, and tried to make the point that the young female students could also aspire to this one day. We wanted to de-construct some ideas that are common in Bolivian society and perhaps even in Latin American society: that say, engineering degrees are for men and not for women. The topic on alliances has also been cultivated and has had an impact on the project: we have alliances with private organizations, and with governmental and NGOs, etc.

What type of support has the project achieved at a country level in Bolivia? How has it been received community-wide?

Licyel: In terms of funding acquisition, we started the project with funding from the US embassy in Bolivia. The first year we didn’t actually have funding – rather, the project started as an exchange of services with the University’s biology degree. The second year, we obtained 1500 USD, which in Bolivian currency it’s 7-fold higher (i.e. around 10,300 Bolivianos), which is a lot of money. This was mostly used for local impact in the city of Cochabamba. In the 3rd version (in 2019-2020) we obtained 3000 USD, but due to the pandemic this was extended to 2020-2021. Then we got funding from a Bolivian private institute to do local workshops. We have presented our projects to the Bolivian government. We have met with the Bolivian minister of education, and with the Bolivian former vice-president Alvaro Lineras, and he for instance, was very enthusiastic about the project. Later, however, in 2019, there was a change in government and a huge conflict between political parties, and sadly our negotiations became stagnant. With the change of presidency it also became complicated to present the project again. But our wish has always been to involve the government and present our ideas. Sometimes it’s not so easy – for instance right now Bolivia is facing a rather tense political situation, so we need external options. A big strategic ally has always been the US embassy which has provided us with a lot of opportunities to have a greater impact, so we are very grateful.

In terms of reception, we have now made two “versions” of the project: one is online and the other is presential. Perhaps Mica can tell you more about the presential impact, and Ale about the online impact.

Micaela: Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the workshops were always in-person. In some schools we were very well-received – the school leaders would be very helpful providing whatever we needed to carry out the workshop – data, teachers who acted as supervisors, materials, etc. The students too, because the workshops didn’t always take place during school hours, but on the weekends. However, sometimes this caused complications: some parents or students didn’t want to come on a weekend, and so we needed to do letters where we needed the school to commit a minimum number of participants for the workshops. Still, while in some schools the support has been huge, in others it hasn’t been ideal: we end up teaching a workshop to 15 students out of 100 who enroll on the workshop. Sometimes the students weren’t so enthusiastic at the beginning, but later, once they were building the microscopes, you could see they were having fun and learning and enjoying their time. They realized they could see things they didn’t imagine such as cells. Some students would be very engaged and would bring their own samples like insects from their garden or plants from their garden. In subsequent workshops they showed even more enthusiasm. We would sometimes get feedback through our social media platforms (our webpage or Facebook), whereby students would also ask for help with different things. This was before the pandemic when everything was in-person.

Alejandra: Taking the project online during the COVID-19 pandemic has been a major challenge. We know the interaction is not the same, so it has been difficult, especially to the volunteers who give talks and teach at the workshops. While for the theoretical part of the workshop didn’t suffer a lot, the most difficult part to move online, is the practical part. On the other hand, I saw that participation also changed a bit: kids who are sometimes shy and might not like to participate in person, online they had the option of turning their camera and microphone on (or not), and this option seemed to increase participation, making things more interactive. On the practical side, it was difficult: starting with the volunteers teaching how to build a microscope, having issues to connect to the internet. Many students also couldn’t access, because of poor internet connection. Some students found it hard to understand the dynamics: they found it difficult to keep up with the volunteers who were building the microscopes, because of poor connection or finding it hard to figure out what the different cameras were showing. This was a major disadvantage of the pandemic. Another challenge perhaps was that, because the practical workshop was also virtual, the students needed to have their own material to build the microscope, so we had a team of volunteers delivering microscopy kits to a specific collection point, where students would come and pick it up. This was sometimes tricky to coordinate, logistically. Still, virtual learning gave us other positive things – we were able to reach more people, and have been able to adapt to the virtual environment to some extent.

Microscopia Para Todos is a very successful and very large project, involving several Bolivian cities in Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, La Paz and Chuquisaca. How do you coordinate activities across the country, and how has it been as an experience, to participate in such a cool project?

Licyel: I think Pame and myself can tell you a bit about this. My team was Social Impact, which was in charge of the project execution. We designed the logistics of the project, from organizing workshops to delivering kits. I always involved friends – I would call them, tell them about the project, ask if they were interested in taking part and whether they knew other people who would like to take part too. We also organized calls for membership through social network and our webpage. We would interview them and have a feeling on the enthusiasm they had. There were applicants who had little to no experience, but who were very enthusiastic and passionate about the project. Conversely, there were a few applicants who seemed to just want the participation certificate but didn’t have the passion. Once we established the team, we sought to identify people with leadership potential, and they became coordinators of specific projects in one of the project’s “home cities”. For each coordinator there was also a sub-coordinator in charge of outreach and logistics. Each coordination team had a team of 5-6 volunteers. Those in charge of outreach, would make sure that the speakers received training. All the volunteers were trained and monitored to make sure that the way we present at the workshops are interactive, and that they use adequate tools – this is more in the sense that virtual workshops brought about a lot of challenges at the beginning. In terms of logistics we had to figure out who would organize and moderate the workshops, who would deliver the kits, who would buy and put together the kits, who would receive and sign for the material, who would get in touch with the schools to organize our visits for the workshops, etc. This was a rather complex process. Once we established all this by city, we constantly met with each coordinator of each department – weekly or monthly. I used to be in meetings every night. This is in terms of logistics. I think in addition to our passion for education, the MPT project also brought us together and we were able to make good friends. I haven’t met all members in person, but we get along very well. I think we owe a lot of this to Pame’s area, which is Human Resources and administration. Her team was involved in team-building, which she can tell you more about 🙂

Pamela: My area is in charge of Human Resources. Thanks to virtualization, we managed to reach out to more departments in Bolivia in addition to the main cities where we are established – i.e. beyond Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, La Paz and Chiquisaca. Within my team there were members from Oruro, Beni, and Tarija. This was very nice – to build a team and collaborate with people from various regions in Bolivia. Our communication was mostly online. Everyone in the team is super passionate. As a first instance for all volunteers, we wanted to increase their potential and give opportunities for growth – we organized training on leadership, the use of various tools, etc, to facilitate the management of and performance within the projects we were coordinating. Internal coordination did not only focus on getting to know all members but also determine what abilities they have, and what new skills and abilities they have learned within the project and in their careers – we have members from multiple backgrounds: not only Biology, but also engineering, journalism, psychology, social areas, etc. This has allowed us to develop various abilities amongst all members.

Licyel: Indeed, it’s important for our organization that not because it’s dedicated to science, does it mean that everyone involved is a scientist. I feel everyone can contribute with their expertise and knowledge from multiple areas. For instance the person who trained all our speakers wasn’t someone from political or public science – he is a civil engineer who loves debate. The person who designed the polls together with the psychology team was a dear friend and colleague from the Biology degree – he immersed himself into everything he needed to know about pedagogical sciences, so this mixture and interdisciplinarity was very interesting as was the focus that each member, with his or her different skillset gave it. Additional to all the meetings we had as a team, the team of directors also met often: myself, Pame, Pablo and Camila. We met together every month to determine whether the objectives of the MPT project were being met, and if they weren’t we worked together to re-direct our work and/or improvise to be able to reach them. We wanted to make sure we were giving our best to the participants in the schools. Each area had its own individual projects related to social impact, human resources, communication, administration or research. For example, within the communication team, a project was to determine what our impact was on the different social media platforms and how to increase our reach. The research team was constantly designing the polls and training, reading more, etc. Anyway – these improved layers came only in later years after trial and error during the first year or two. When we started we were a very small team, compared to today’s team. We were only 50, and all in the same city.

I see you can get involved as an education unit, as a strategic ally, and as a volunteer. Can you tell us a bit about what it involves? Do you accept international volunteers?

Licyel: The idea for education units is that schools can register their interest to participate in the MPT project. This allowed us to make a database, which we could contact in due course to organize the workshops. This was happening anyway through our acquaintances: for example my uncle is a teacher, and he would call me to tell me he had mentioned the project to his colleagues in other schools and that they were keen to get in touch. But we realized it would be easier if we designed a webpage for schools (and also universities) to be able to contact us. The other big group are volunteers: through our website, they can leave their contact details and when we have calls for members, we have that database of members whom we can contact too. Before we created the webpage, a similar situation as with education units would occur: interested participants would contact us through our social media and ask us when the next call would be. The database allows us to have a better organization with the compiled contact details of everyone who has shown interest to join. Finally, for strategic allies, this includes for example organizers of STEM activities in different parts of Bolivia, or potential funders who might want to get in touch and get to know us. We didn’t always know how to reach them, so the website also allows them to get in touch with us. Perhaps a problem we face now within Bolivian society is that not everyone uses websites to contact us. We get more contacts through social networks, so where we are more present is in social networks – we are always checking interest and potential collaborations. We are on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and Linkedin. We don’t yet have Twitter – it is still a project in motion within the communication team! The thing is managing each account requires volunteers who constantly update, monitor and upload new content, so there’s only so much we can do – currently in 5 platforms.

This is such an inspiring project, which could be a basis for similar endeavours in the region. Do you hope to/ wish to expand your reach beyond Bolivia?

Licyel: Currently our outreach is at country level. We taught foreign teachers at a point, who showed interest for the project. We also have had foreign volunteers showing interest, but we have prioritized Bolivian participants mostly because this was one of the aims in the grant we wrote (and got awarded by the American Embassy). Also in terms of logistics, we deliver kits with the logo and all the necessary material for the workshops, which the students get to keep, so we didn’t want inequity in terms of some students not being able to get access to this material. We would love to expand the project beyond the Bolivian borders, but we still need to solidify the structure of the project within our own country. Because of the political issues in Bolivia as well as the COVID-19 pandemic, we had to constantly adapt and make the project evolve. In this post-pandemic stage, we want to make sure that the team in Bolivia is very solid and stable before we venture and expand the project to other countries in Latin America. This would be optimal! We feel lack of access to microscopes is not something unique to Bolivia, and solving this in Latin America would be a huge step forward in the entire region. A challenge to consider, perhaps not uncommon in Latin America is that the promotion of STEM disciplines is sometimes received with skepticism if not rejection: when you tell a student from a family that has barely enough money to eat, that they can pursue a career in STEM, it might feel out of touch, when they might not even consider University, but rather getting a job as soon as possible to be able to contribute to the family’s income. I feel incredible frustration when I see a very passionate student who cannot pursue this interest in science because of their socio-economic reality. This is heartbreaking, because it’s not an issue we can eliminate at all. What we try though, is to inspire the students, using examples of people who share a similar background/ social context as their own: who worked in the fields and attended public schools. We want to give the message that any dream is reachable, and it’s worth giving it a try. To give them options for them to decide. This is something we wanted to address with the government too: to promote microscopy as something that can be incorporated in the school curriculum. But indeed, to reach the government level has been very tricky. It’s difficult to send the message in developing countries with lots of basic needs that need attention, where investment in science is considered a luxury or something only for the wealthy. We know science plays an important role in a country’s development, but it’s a tricky message to convey.

INDIVIDUAL QUESTIONS

What inspired you, personally to become a founder, participant, or volunteer in this project?

Licyel: For me it was the fact that I studied in public schools all my career. Access to opportunities in science changed my life, especially access to funding in the form of fellowships and scholarships took me to places I never thought I could reach. Being able to give this same chance I had to Bolivian students was something I really wanted, in one way or another. I wanted to convey the message that if I was able to do it, I wanted others to reach even further. As we discussed a bit earlier, while science is a luxury it’s also a need for the development of Latin America. My main drivers were my passion for education and wanting to extend these opportunities to young students from all socio-economic backgrounds so they can access opportunities sometimes restricted to the wealthier kids in our society. Information and education should not be a privilege, but rather a constant. I don’t see why inequities in education should exist. We want to bridge the gap between public and private schools. Talent is present everywhere, but the way we harness it is what we should improve on as a society.

Micaela: When I think about how I got involved in the project, I say I got on a train that was already moving forward. I love Licyel’s idea and I joined it. I actually started studying something different to Biology because I didn’t know this degree even existed, or what the role of microscopy was. I would have loved if I had received some orientation from young scientists (like ourselves now) who would have told us what the various options were. Many people still don’t know that one can study some STEM disciplines (like Biology or some engineering sub-disciplines such as forestry or environmental engineering) in Bolivia. I want young students to be aware of the choices so they don’t have to make a career change later on, like I did. When I started getting involved as a volunteer, I started noticing other things, like fellowships and other opportunities. I’ve learned a lot through the MPT project, and I’ve loved being able to open those doors to other students too.

Pamela: There are two main experiences in my life which I think were important for me to be able to get involved in this project. The first is that I switched from a public to a private school. The private school was not per se private – it was a religious school ran by German nuns. In this switch, I was able to see the contrast between a public and a private institution. In the public school I didn’t get to study a lot of STEM disciplines, but in the private school the most involved people were my teachers, who motivated me to pursue my current career. Also, my mum is a teacher, and she did her years of service in a province called Sorata. She took me there several times, and I was also able to see the huge contrast between a public school in a big city compared to one in a little town. Many students in Sorata, for example, didn’t have shoes to go to school. This was a huge impact in my perception of inequity in terms of education and opportunities. The second big experience was at University. I was a teaching assistant for Chemistry. My teacher, who passed away, was a great mentor and he helped me in my career. I tried to be as motivating to my students, and many of them have expressed their gratitude. Afterwards, I saw the impact of MPT and I realized this was something in line with my goals. I saw that their reach was not only at a classroom level like I was doing, but at a much greater scale, at a country level. I fell in love with the project. I am grateful to the entire team – the project was born in Cochabamba, and I am from La Paz, so I actually joined later. The team motivates me a lot.

Alejandra: My main motivation was that I studied in a private school in a rural area – very far from any city. My school didn’t have microscopes – in fact there was no practical part for Biology at school. I didn’t know the career of biology existed – or any of the STEM disciplines. My idea was to study Medicine- I thought it would be the degree that would bring me closest to what I wanted to do. So I was ready to enter University (the medical degree), but I am grateful to the people whom I met in my path, who guided me into a different direction and made me aware of the possibilities. I believe I would have otherwise studied a degree, and would have started a career that I probably would not have enjoyed and might have quit half-way. I am happy to have joined the degree of Biology, and I don’t regret the decision at all. In the first semester, I was so excited to see the syllabus. During the first year, Licyel gave a very motivational talk about different opportunities, scholarships, etc. I also became aware of many extra-curricular opportunities. I realized I wanted to leave my comfort zone and not limit myself to the confines of my career, but learn as many things of my interest as possible. In this way I found out about MPT, and joined two areas: communication and social impact, and it has been a wonderful experience. It has allowed me to reach students and open doors that I hope has made a change. Equally, belonging to MPT, it has allowed me to grow and develop my abilities too.

What is the thing you have personally enjoyed the most about the project, or the biggest inspiration? And the biggest challenge?

Licyel: What I have liked the most is to see the excitement in the participants, when they see samples under the microscope, for instance cells from their own mouths, to discover the micro-world in their own bodies. Some of them have expressed their gratitude to us for showing them something new, as well as the new possibilities. Out of the 100 students we include in the workshop not everyone will become a scientist, but if we reach one or two, this is a huge success already. The second thing is the friendships we have been able to build. I met many of my MPT colleagues during the degree, and now 4 or 5 years after, many of us are pursuing graduate degrees or jobs. Now everyone is more mature and “grown-up” yet everyone is equally engaged and committed to education and society. I’m very happy that MPT has played a role in their development as leaders and agents of change. In terms of the biggest challenges, perhaps the two that come to mind are funding acquisition and implementing something stable with the government. The US embassy has had a huge impact on the project, and while it has been fantastic to work with international funders, local investment is important- we wish the local government would get involved and support projects like ours. Otherwise the message is that European and American organizations want to support science in Bolivia, but there’s little interest “at home” to do so. It’s important that locally we see the need to do science. Another challenge I can think of is finding work-life balance. One has to fit together our work at MPT, science, our education, our family, our leisure activities, etc. In the end I think it’s worth it – we are passionate about the project, but it’s certainly not easy to find or maintain a balance.

Pamela: What I love most about the project is that I oversaw the transition from presential to virtual. I saw huge enthusiasm amongst the participants in the workshop, who would be at home attending the workshop virtually and would be keen to bring a sample from their garden or elsewhere to learn more about it. I met many students who gained inspiration from our project, and wanted to pursue new projects they hadn’t envisaged before. One of the challenges has been the logistics of trying to reach more people: for instance once we had applicants who wanted to participate in the workshop but we ran out of kits because we had no more funding. We need more support to be able to reach more people.

Alejandra: What I have enjoyed most as a volunteer is seeing the young students eager to learn more. That common things like onions, bills, insects, coins, are super interesting in the micro-scale. They would sometimes go to their kitchen or garden and bring something new – seeing their excitement is something I find exciting. It’s been a rewarding experience. Their interest doesn’t end with the workshop – many students would contact us afterwards to ask more about microscope, or about opportunities, and would ask us about our experience. For me as a volunteer in social impact, I’ve received many messages from participants, telling me about the impact our workshops had for them. One of the challenges for me as a volunteer was to deliver the correct information. It’s difficult to provide information to young students because sometimes they don’t have the full background, so we had to be able to convey information in the most concise and simple way possible, with an accessible language so everyone can understand. So we, the volunteers, undertake training to be able to achieve this.

Micaela: I think I agree with everything my colleagues have said. I didn’t know that the student’s excitement to see new things under the microscope, would be so motivating to me. I am excited to be able to bring the workshops to new places, and share this experience with as many students as possible. I also think one of the best things has been to meet the people in the MPT project – to know about their path and share this new path with them. In terms of challenges, I used to find it hard to speak in public, so teaching in the workshops I would be extremely nervous. It was super complicated for me to convey the message and make it exciting for the students. But with time it has become easier and I have overcome my fear. Another challenge is that as the project has evolved, it has involved more volunteers, and leading so many people is daunting. But we have received training on this too, so I have personally grown a lot.

Through your project, you have the chance to interact with a huge range of communities. What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Bolivian scientists?

Licyel: A scientific career is not easy – like anything in life. Yet it’s exciting and fascinating. It will always make you challenge yourself and it will make you ask yourself a lot of questions, some of which you might sometimes feel are too basic. Yet it is in the small things that you’ll find beauty. Science is not determined by where you are from, or who you know, but what makes you passionate about it. These can take you not just to a path of science, but also to a path as a communicator, or politician, or if you belong to a different area and you wish to switch you can always do so. Whatever area you choose, let it be something that really makes you excited, because it’s something you’ll do every day. Whatever you choose, be prepared that it won’t always be easy. This is a myth, that if you’re passionate about something, it won’t present its own difficulties. This is not true. For example I’m doing my MSc degree, and I am tired of exams. I’m waiting to publish my first paper to call myself a real scientist 🙂

Micaela: I think what Licyel says is true: science is complicated. It’s a complicated career. But I agree that you should do something you love and enjoy, as you’ll likely be doing it every day. It’s important that you like it. That’s why I changed careers. Some people might tell you, “why will you study science – how will you survive if the pay is so little?” but it opens a world that maybe other people don’t see. It’s a wonderful world. So pursue your dreams, and follow what you love.

Pamela: A piece of advice I could share is that you should find what you love and be curious about this. Unluckily many people are forced by their parents to pursue a specific career, but the idea is to do something you like and that you can make a living out of what you like. If you like it, you’ll find a way of achieving new things within that career. Otherwise, it’s complicated to do something you’re forced to do. Besides this, give 200% of your effort into your work – nothing is free in life, and you must build something first to achieve your goals later on.

Alejandra: As an undergraduate student still, one piece of advice I can give others is that you should study something you really like. Being the best at something you don’t like is pointless in the long run. Pursue what your heart truly wishes, no matter what other people say. I’ve been told that my career has no future, that I’ll never find a job. Despite all the discouraging comments, I’ve tried that these don’t interfere with me or the pursuit of my dreams. So my advice to you is to stay the course. Fight for your dreams, leave your comfort zone, expand your horizons -there are a lot of opportunities. The biggest barrier to leave your comfort zone is fear. So despite the fear, give it a try. If you fail, learn from your failure. If something doesn’t work the first time, the second time around you’ll do it better.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Bolivia a special place to visit?

Licyel: I’ll summarize it in 4 key points: number 1 is the food! Bolivia’s gastronomy is incredible. Second are the landscapes – while I’ve still not been to the Uyuni Salt flat, this is something I will definitely fix in the future. The third thing is the people – people are always very welcoming. The fourth are the problems that the country faces! It keeps you awake and on your toes, because there’s always something to solve. So, obviously ideally there would be no problems, but in those problems you find opportunities to improve, innovate, etc. Perhaps if we had been born in a place with all the opportunities and political and economic stability, you wouldn’t be able to learn what you can learn in a developing country. I’ve seen this a lot in my case: coming from a developing country is tough, because when I finished my undergraduate degree, I didn’t have the same academic level as students who were born in the Global North, but growing up in Bolivia shaped me in different ways. It has given me a great opportunity for learning and growth.

Micaela: I agree with Licyel: food is very varied and food diversity very rich, especially in Cochabamba. We are known throughout Bolivia as the food-enthusiasts! 🙂 Also landscapes are very varied and very beautiful. We have Los Yungas, Amazonian jungles, the salt flats, the swamps, and a wide variety of climates. If ever you have a chance to come to Bolivia, you’ll see it has everything to offer. The culture is also very rich: we are a pluricultural country. People are very warm-hearted everywhere and very hard-working too. I think that’s the main things I love about Bolivia. I’d encourage you to visit.

Pamela: Food is the best things about Bolivia! I think one only realized this when one goes abroad! One suffers abroad without our nice food! My family is from Cochabamba, which is indeed a food-enthusiast region. The landscapes are also super diverse and wonderful. There’s a huge contrast between east and west of Bolivia: the culture is very different and the people too. Still everywhere, people treat you as if you are family. Whenever I am abroad, I do miss my country very much.Alejandra: Food is indeed the best thing, and biodiversity too. I’m afraid I haven’t traveled enough within my own country. Only very recently I traveled to La Paz. I used to think there would be nothing in La Paz, except for mountains – not even trees. But of course that wasn’t the case. The east and west has a lot of contrasts. The culture is also something very rich. When you do a field trip and you meet other people, you get to see the traditions and older culture in the country. One thing I love about the people in general is that Bolivians are very hard-working. They are very keen to succeed and contribute to their country. Young students want to be the best version of themselves, and this is very fulfilling.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)