An interview with Rosa Isela Gálvez

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 23 May 2023

MiniBio: Dr. Rosa Isela Gálvez is currently a postdoctoral fellow at La Jolla Institute for Immunology, where she is characterizing human T cell responses to different viral pathogens, vaccines and exposed populations in endemic regions. She has done most of her career in Germany. She studied her undergraduate degree at the University of Hamburg. She later did her postgraduate work at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (BNITM), focusing first on the Plasmodium parasite, and later on Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi) the causative agent of Chagas disease. The latter is a long-term passion for Rosa Isela. Her long-term dream is to contribute to the better control and epidemiological surveillance of neglected diseases in Latin America, and in specific, her native country, Peru. She is currently a collaborator of the Peruvian Ministry of Health, for the establishment of guidelines for the diagnosis and control of Chagas disease. While currently her focus is on big data on human Immunology, her work as a parasitologist has led her into the path of microscopy.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

My parents are both medical doctors, but my dad was born in a family with little resources in the Peruvian Andes. When he was 12 years old, his family ‘shipped him off’ to Lima, and basically instructed him to either become a policeman, a lawyer, or a medical doctor. Still, I was born in a middle-class household with two physicians as parents. Both of them worked in public hospitals, and this was particularly impactful given the many periods of instability which Peru has been through in the last few (or rather many) decades. It was a struggle to even get antibiotics. My father worked in a renal transplantation unit – with patients who could actually afford a transplantation. My mother, on the other hand, was working in the National Pediatrics Hospital where resources were really scarce- even antibiotics. So, I grew up in this world of diseases, antibiotics, infectious pathogens, etc. Peru is endemic to many infectious diseases, and while the population is not always aware of all the diseases, there is a widespread fear for infections that cause disfigurement, such as leishmaniasis. All this was defining for my life. However, I never really formed an expectation of becoming a physician or a scientist. I lived in a world in which I was interested in pathogens and insects mostly. Something that left quite an impression was my social service, which I did during the 4th year of high school (a catholic high school). I went to the north of Peru, almost at the border with Ecuador, on a program where we work for 3 months providing different types of service: from vaccination campaigns, to dentists – it’s a lot of expertise and professionals from many areas dedicating their time to offer these resources in these impoverished regions. I suddenly realized that there was a completely different reality to the one I was used to. Even different to the one my grandparents had experienced in the Peruvian Andes. The Andes are cold, but there’s a lot of resources and agricultural wealth. In the North of Peru, it’s a dry region with lots of poverty. But there were many local and foreign scientists working on social projects addressing many tropical diseases including Malaria and Chagas. It’s not uncommon that a young person might be playing football and suddenly collapses – and is later diagnosed with Chagas disease. I was super impressed by this, and by the level of neglect of the population in this area. Many of us suffered from Dengue and Malaria during this time. We suffered from high fever, and the program organizers basically put us on a plane to send us back to Lima to get proper medical care. But what about the people from this area? There was only one small post where a nurse would pass by every one or two weeks, and that was about it. There was nothing else in the sense of medical care. It was at this point where I became fascinated by tropical diseases. But I still wasn’t sure that my calling was towards Medicine.

In fact, I started my training at la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Peru, and I was in the first generation that started to study Performing Arts. After a few months I reached the conclusion that this was not going to be very productive because University in Peru is very expensive. Since my parents were medical doctors, I had to pay the highest fees. And my family didn’t understand where this career was taking me. I also wasn’t sure this is what I wanted to do. So, for the sake of my peace of mind, I decided to go somewhere in the world where education was free of charge. My list wasn’t very long: it was either Sweden, France or Germany. But in those times, the Internet wasn’t yet a thing. I was using Altavista! So how to figure out the process of immigration, when I didn’t know anyone at all who had done it? I went into a blog of ICQ and posted a message. I got contacted by people, and somehow, I ended up contacting a family in Germany. I blindly trusted they were nice family, and they blindly trusted I was a decent person! They sent me an invitation, and I went as an au pair to Germany. But, although I went as an au pair, my whole future was perfectly planned in my mind: I took with me all my documents already translated to German, and ready to become fully proficient in German within 1 year. In one year I needed to enter the school for foreigners, and within a year I should enter the undergrad degree at some University. That year prior to the undergraduate, is compulsory for foreigners wishing to enter a German University. Because it’s a very tough program, not many people choose Mathematics or Physics, or exact sciences. They choose literature, or something under those lines, where even your native language is revalidated as one of the subjects. So, I was told by my adviser: “If you want to join University as soon as possible, you should study the courses relevant to degrees that everyone avoids, like engineering, or biomedical sciences and Medicine.” But I also figured out during this time that someone who is capable of learning German, surely can learn anything it’s such a difficult language. Thus, I chose the courses to be able to join Medicine, but this didn’t work out either for one simple reason. I became pregnant with my eldest son, Lukas José, during this time, and I went out on medical leave. And then I entered a logistical labyrinth – it became super complicated. Anyway – I obtained the German nationality within 2 years, but in doing so I was no longer eligible for the vacancies that the medical schools open for foreign students. For application purposes, I was considered German. While I didn’t get a place in Medicine, I decided to study Biology…. And that’s my story, of how I ended up in science 🙂 I’m very practical really – there’s always plan A, B, C, and D.

You have a career-long involvement in immunology, cell biology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

I studied my undergraduate and MSc degrees at the University of Hamburg and did my PhD at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (BNITM) also in Hamburg. I think the beauty of Biology is that it’s super extensive – in Hamburg you touch on all the topics, but you don’t really go in depth. It took me a while to finish my Bachelor’s degree. In Germany it would usually take 3 years, but it took me 4.5 because my second son, Diego Elias, was born during this time. I wanted to work at the BNITM, and I was offered to work on a project on vitamin B12 and Malaria parasites, but since I was pregnant, I would not be able to work on several assays which involve a certain level of toxicity, so I didn’t join that lab. I ended up doing my first project on UV-induced carcinogenesis of skin cells, in a lab that aimed to understand sun radiation and its impact on malignant tumours. During my Masters degree I attended two courses that matched my interest: Molecular Parasitology and Immunology. I fell in love with the topic of Immunology of Infectious Diseases and realized I wanted to stay here. It was around this time that I asked Thomas Jacobs if I could do a PhD in his lab. He suggested working on T. cruzi (causative of Chagas disease) and this was sensational, but he told me that the last person to ever work with T. cruzi had left 3 years ago and he had no funding for that. Malaria is his lab’s expertise. He asked me whether I’d be interested in working with Malaria – so I did my Master’s degree studying immune responses in murine malaria. When I finished, there still was no open position or funding for Chagas. Obtaining funding on my own was basically impossible too, because I was already 33 years old, and you know how it is in Germany. Funding for early career researchers is age-limited, more or less until you reach the age of 30. Especially as a mother of 2 young children, to work on a topic for which they have very little interest: it’s a neglected tropical disease from Latin America. Despite this, I applied everywhere and finally got a fellowship for 4 years – which is plenty. I didn’t get a lot of funding for consumables, but my PI (Thomas Jacobs) offered to provide this. It was still complicated though: I underestimated how difficult it would be to work on an organism on which there was no expertise at all in his lab. This is a limitation in every way – moreover, T. cruzi is a BSL3 organism, so you’re limited in what you can do: you can’t do flow cytometry or high-end microscopy because these instruments are not available in BSL3.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Peru, from your education years?

There are many things! In general, culturally and in terms of education, my upbringing was well-rounded. I didn’t find it difficult to learn. I finished school in December of 1997. I lived in London at some point between these years and had no problem at school. Back to Peru, University. Then went as an au pair to Germany, I started the first part of the German high school in 2002, my child was born in 2003. In this time, Germany didn’t have full day “Kita” or daycare. I started my Bachelor of Science in 2007. But despite the many pauses, I didn’t find it difficult to re-integrate into the education system at any point. I feel the education I had in Peru helped me a lot to be independent. My school had a philosophy and teaching style where each student was responsible for organizing their courses, their learning, and their responsibilities. I think this is important for young people. You get to know yourself too. So, for me this was super helpful. It taught me to think rather than just consume content. This has been relevant to my whole career.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a researcher at La Jolla Institute for Immunology?

The lab where I am now works in a way that is totally different from the one I used to work at before. I used to work with mouse models and didn’t have access to large human cohorts. I also had in vitro models, where I was able to use microscopy. Now, I am in an institute where their specialty is human immunology, particularly T cell responses to vaccines or natural infections. This allows us to compare responses to different vaccines. We have access to samples obtained in San Diego, but we also have a many of collaborators, for example, the effect of dengue infections in the Philippines in children’s cohorts. We participate in longitudinal studies with huge cohorts. I’ve had to learn how to handle a huge amount of data. I am still optimizing how to analyze the largest amount of data, with the least amount of effort, and the highest amount of automation. I am learning a lot of Bioinformatic tools and optimizing immunology techniques. They have super advanced equipment to do flow cytometry which allows you to use panels of over 27 colors. It’s super interesting. Since we have access to such huge cohorts, the techniques we use are super complicated, but the translational relevance of the work we do is very high.

When I finished my PhD, I wanted to join a lab specializing in T. cruzi in Atlanta, or at John Kelly’s lab in London. But I needed to figure out what exactly I was going to learn, which would be different from my work during my PhD. There were two options: to become more of an expert in parasitology, or in immunology. My dream was and still is to investigate neglected diseases in Latin America. But in my experience, it was always difficult to work with big cohorts, and it takes quite some time to organize big teams and collaborations that allow this. I tried this during my PhD with some level of success. Moreover, while I was a PhD student, with no publications on T. cruzi, nobody took me seriously when I proposed collaborations. Now that I have gained some credibility, I have gotten more positive responses at conferences and congresses. So, I came to La Jolla because they offered techniques I was very interested in learning. They are mapping the full genome of viruses by cutting the genome into several overlapping peptides, and identifying what is the most immunogenic segment of the virus. As you know, working with viruses is very different to working with parasites. But while I am here learning these techniques to better understand T cell immunology, my dream is to later apply it to the pathogens I am interested in, like Plasmodium, T. cruzi and Leishmania of course.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Peru?

Sadly no, but I feel it’s something that is improving. Because of my work in Hamburg, I was involved in raising awareness, and coming up with recommendations for general practitioners to be able to treat patients who are potentially infected with T. cruzi. Among the European countries, Spain already does a lot in terms of screening and treatment of Chagas disease, but it was something not so well established in Germany. I gained a bit of visibility because of my work, and I became a reference for some projects. So, recently, the Peruvian Ministry of Health came in touch and asked for my input and whether I’d be interested to collaborate to re-design the line of treatment and diagnosis. A Colombian colleague who was working in the same lab as I am now, has also become a strong collaborator introducing me colleagues in Colombia. I’ve forged other collaborations with scientist at LJI. I think a limitation I face when it comes to connections is that I didn’t study any of my degrees in Peru. Now that I’m going back to Germany, I have a huge network, which I simply don’t have in Peru. I’m lacking a peer group.

Who are your scientific role models (both Peruvian and foreign)?

What a difficult question. Prior to my PhD I didn’t have a lot of time to do practical’s in different labs. My life was all about running to pick someone up from, or drop someone off at daycare. And we needed money to survive, so I had to take jobs on the side, in addition to my studies. I had to stop working on weekends when I started writing my MSc dissertation because otherwise I felt I would just die one day. I re-started working at a restaurant during the PhD because the PhD salary was simply not enough. So, I was too busy trying to basically survive. So I was super inexperienced. But I had a boss at some point of the undergraduate degree who had the vision to give everyone opportunities- her name is Dr. Beate Volker She wasn’t so interested in what I already knew (which was great because I hadn’t done much. I hadn’t done IFAs, or flow cytometry, or even cell culture), but rather, she was interested in people’s potential. Moreover, she gave me a great opportunity and taught me not to create false expectations, especially for myself, because otherwise things become a suffering instead of a joy if you’re constantly running around and still falling short of your own, perhaps unrealistic, expectations. She taught me to define the range in which I can be productive and enjoy the work I do. This piece of advice has helped me define expectations for myself and for everyone around me. So when I had my interview to start my MSc degree, I told my prospective supervisor at the BNITM that I had two young children, and that I was never going to be either the first one to arrive in the lab, nor the last to leave. I told him I would do all my work from A to Z, and more if possible, but within my limitations. I feel that if I ever supervise younger students, I would give them this piece of advice too. It’s funny because when I was a student in Beate’s lab, I didn’t really appreciate all the value of her philosophy. Now that I’ve worked in 4 different labs with different leaders, I appreciate this a lot more. She also opened a lot of doors for me: before working in her lab, I was working at a warehouse, packaging products, cleaning, taking care of other children too. But she offered me a job in her lab where I learned a lot, and this slowly gave me the opportunity to exchange my jobs elsewhere, and at the same time gain lab experience. She also offered me the chance to work in industry while working in her lab. Altogether, I think she saw me as this young woman with a lot of energy but without any sense of direction, and she became a guide.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Peru, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I must say I found it impressive that gender (mis)balance in Peru was very different from the (mis)balance I found in Germany in 2000. I came from a family where my mother always worked and was in positions of leadership, even as institute director. My grandmother also was very independent and resourceful. There was no real option of women staying at home while only the men had paying jobs. So at least professionally, this was the reality I knew, where there was no gender gap when it came to the labour force. All the women around me, growing up, had paying jobs and were professionals. So, it was a huge shock to me, when I was in Germany and became a mother. I suddenly had to depend on many institutions which are organized by the state, and realized there was a huge deficit in infrastructure and structure that would ensure daycare provision. This basically negates women from returning to work. The demand for daycare services was very low. There were many highly qualified women who, upon having children, would not return to work. Which is perfectly fine if that’s their choice. I was just amazed by the disparity – in Peru, in many households, this option doesn’t even exist. But in the last 20 years (my son is now 20 years old), things seem to have changed in Germany. A lot of this has come from individual initiatives: if the state cannot organize it, you have to. In the end, I promoted an association at daycare, to demonstrate to the state that there was enough demand of daycare for longer hours. So now daycares are open until 5pm. When other people realize this is necessary and useful, the state moves in this direction with its initiatives too – at least in Germany. My second son was born in 2009, and at this point Germany had even implemented paternal leave, allowing the men to also share childcare duties. My only criticism to this, is that in Germany this is still optional. I criticize this because it still creates disparities in job opportunities. For example, if a hiring manager will have the option of hiring a man or a woman, if they hire a woman, it’s 100% sure she will leave in maternity leave. The man has a 50% chance of choosing not to take paternal leave. If it was compulsory for everyone to share childcare duties, gender wouldn’t be a decisive factor for career progression. There’s still room for improvement. Also specific to Germany, there’s also room for improvement in terms of taxes, related to gender. But on an individual level there’s also ingrained things we should change and I see this everywhere around me: for example, independent of laws on gender, it’s still highly ingrained that if a child is sick, it’s the mother who “should” take time off to take care of the child, and the mother even preferentially chooses to do so (when her partner is equally capable, and it could and should be a shared duty as parents). When I decided to do a postdoc abroad (in the USA, where I am now), my children’s father was very supportive. When my youngest son decided he would not move from Germany, people around me were shocked that I still went abroad without my children, and that they stayed under their father’s care in Germany. If it was a man who chose to travel away, and the children stayed only under their mother’s care, nobody would care or make comments. I feel sometimes we as women don’t want to “give away” or let go of this “power” or this notion that only us (women) can raise and/or take care of a family. But that’s a very personal opinion.

Are there any historical events in Peru that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

Hahaha I think in Peru we just go from one major historical event to the next, non-stop. There’s been a lot of instability: we had many years of terror before Alberto Fujimori, then came 10 brutal years under Fujimori’s regime (between 1990 and 2000), then a little bit of calm and peace, and then in the last 6 years we’ve had 5 presidents. I rather wonder, how one can do science in Peru at all. When I’ve approached colleagues in Peru to collaborate, the mindset is to try to implement short-term solutions, with little resources, and no assurance at all about the outcome. Political changes are super abrupt, and this negates long-term planning in any way. As we speak, Peru is in a state of emergency. During the COVID-19 pandemic we had one of the highest rates of mortality, then a cyclone hit, and now a major part of the country is flooded. I wonder how people manage to meet deadlines, save money, etc. Let alone science – I wonder how people manage to go through their daily life. For example, the Latin American Conference on Dengue was supposed to take place in 2020 – this didn’t happen because of COVID. It was pushed to 2022, and there was an issue with the presidency, which led to the Conference being postponed. Now the country suffered natural disasters. The meeting is scheduled for November 2023, but the Customs and Borders protection of the USA does not recommend traveling at this point to Peru. With this recommendation, foreigners (or even nationals) cannot go to a professional event. So how can one even organize a conference? I find it surprising that science can be done in Peru at all, with this enormous level of uncertainty. Another thing I must add is that many people in Peru don’t know exactly what we as scientists do, or why or how it is valuable. It’s not a product we sell, it’s not quantifiable in terms of profit, and experimental sciences carry a high level of uncertainty per se. This, combined with perhaps a failure from scientists to communicate with the general population on what the value and need of our job is, results in science being seen as an unnecessary “luxury”, especially in developing countries where there are so many needs to be addressed. I think this needs to improve a lot.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Peru?

When I was 16 years old I went on an exchange to the UK. That was the first time I was a foreigner. Then I went to Germany, where I was also a foreigner, and now I’m in the USA, where I’m also a foreigner. There are good and bad things about it. I had never really stopped to think about what the challenges I faced were, because I was so full of things to do for myself career-wise, and my children. So when I arrived in the USA, I got this onboarding where they teach us about inclusion, harassment, discrimination, etc. I reached the conclusion I’ve been a minority my entire life, since I left Peru. In Germany, we were only 2 foreigners, and the rest of my colleagues were German. I am also a woman, and a young mom. I hadn’t seen all the signs that I am a minority, which I guess is a good thing. But the tone in Germany changed after the asylum crisis. In 2015, Germany opened its doors to asylum seekers and refugees, but despite the government’s good will, it became “trendy” in Germany to be extreme-right wing, and label anyone foreign as a parasite to the German economy. It became more common to suffer aggressions and receive nasty comments that made me feel unwelcome. And worse of all, it made my children feel bad too, even though their only home is Germany. I feel really sad about this. I found this shocking that peace was so fragile. It’s a narrative that suddenly many people react like “yes, you’ve never really belonged, we just hadn’t told you”, and now that it’s “ok” to say things like this, many people do. Honestly now in San Diego I feel at home too. Because of the large Hispanic population in the USA, I don’t feel different. I am at the queue in the supermarket, and no one around me knows if I’m first generation, or a visitor, or on a green card, or anything. There are women with a fully Latin American name, who don’t speak a word of Spanish, because they were born in the USA or have lived their entire lives here. I feel happy not being different to everyone else. And now I feel very self-conscious in Germany. It’s nice to be a world-traveler, but in the end how do you define “home”? Then again, there is a lot of racism in Latin America too, and it’s a difficult conversation to have even with relatives and friends. There have been major crises in Latin America, leading to massive migrations – which result in the people re-settling, facing huge discrimination – even in “sibling” countries like ours in Latin America, where we share culture, language, religion, and many other things. I’m surprised at the general xenophobia worldwide. We don’t even have to go so far: indigenous people and people from regions with lower resources face discrimination in their own country.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

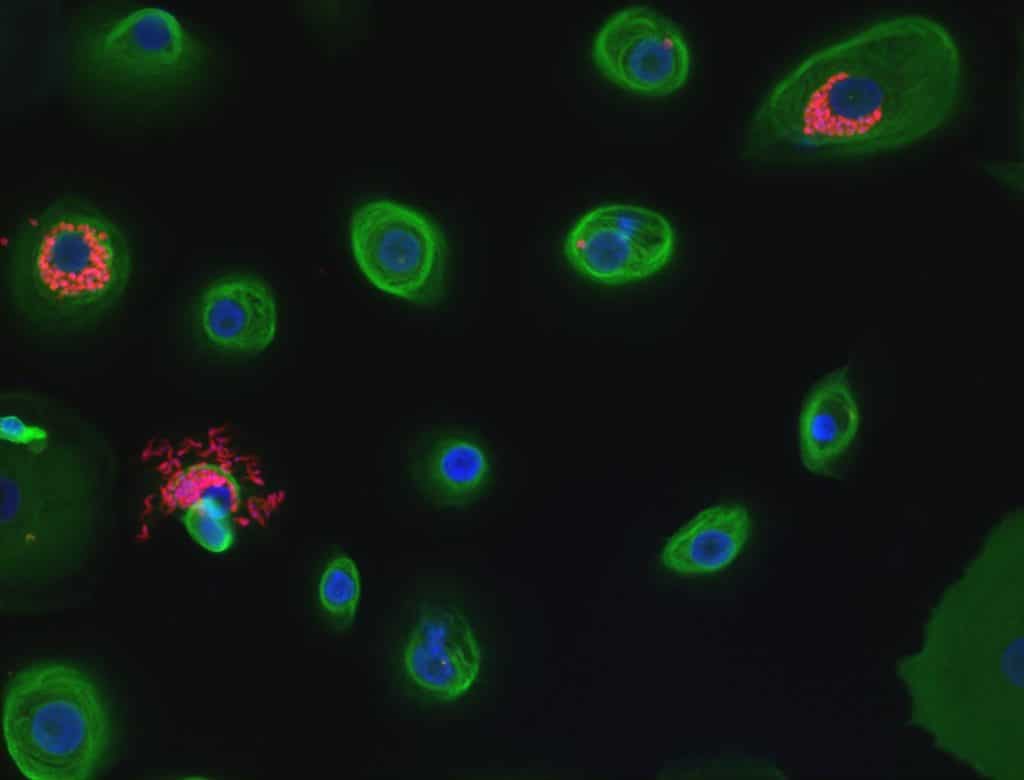

At some point during my PhD, me and one of my students were quantifying parasitaemias – in the traditional way whereby you get a counter and ‘click click’ endlessly – to determine how different antibody treatments acted on the immune response against a parasite. During a seminar at the BNITM, a student from a different lab introduced a machine that their lab had just bought, called OperaPhoenix™ from Perkin Elmer, which is a high throughput multi-channel confocal microscope. That’s when I had an ‘aha’ moment – the idea of using this machine to answer our questions on T, cruzi. It allowed us to determine the border of the cell, the nucleus, the mini-nuclei of the T. cruzi amastigotes, allowing us to calculate the number of trypanosomes per infected cell. We could then do a co-culture with our immune cells of interest (i.e. NK cells) and determine how many parasites/infected cells were killed. It’s fascinating!

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

For me those images of one infected keratinocyte with all the T. cruzi amastigotes, and then an NK cell on top of it, killing it’s one of the most fascinating things I’ve seen. I printed this and it’s even in my office.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Peruvian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

I would say, the academic career is a marathon, not a sprint. You have to save your energies in order to be able to continue, and continue and continue. It’s not even a marathon – it’s more like an IronMan. The other piece of advice is don’t be afraid to ask people for help. Very few people in my career have ever refused to provide help. You should be willing to and mature enough to ask for help, and trust that you will receive it.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Peru, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think without political stability, it’s difficult to plan collaborations or even hold scientific events. I hope there will be emphasis in the topics that are important for Peru. We have a huge amount of diseases in Latin America, all together in this cradle. We should be prepared for any global threat. The COVID-19 pandemic had such a huge impact in Peru because we lack the infrastructure. Without infrastructure we cannot provide basic healthcare. People without access to healthcare cannot develop to their full potential. I think more stability and investment in infrastructure for healthcare is a must. How I hope to contribute? Continuing to work in neglected diseases which are well…neglected by a lot of the healthcare programs. There are endemic diseases such as Chagas, and serious diseases with a huge destructive potential if they get out of control, like Chikungunya, which circulate in countries like Peru. Epidemiological monitoring and surveillance should improve in Peru, and I hope to be able to contribute in this respect. I’m happy that the Ministry of Health invited me to contribute to the guidelines for the control of Chagas disease, and I hope it makes a positive difference.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Peru a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

Food is great!! I love Peruvian food. And that we take everything with humour. I think that being in touch with people from my own cultural background allows me to see things in a more relaxed way.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

I think Rosa’s story is admirable and above all very sincere about the reality of Peru, Latin America and the world. I think it inspires us to be better every day as people, as a country and as humanity.