An interview with Jose Antonio Baptista Machado

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 20 June 2023

MiniBio: Dr. Jose Antonio Baptista Machado is a principal investigator and lecturer at Universidad de San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador, where him and his group focus on the study of biofilms. Antonio studied his undergraduate studies in Evora, Portugal, and his graduate studies in Minho, Portugal. After finishing his PhD in 2014, he was recruited by USFQ to join as an independent group leader. Antonio’s passion for microscopy was awakened when he started working on Microbiology, and it’s something he wished to continue to develop in Ecuador. In this interview he tells us about his transition from PhD to PI, while changing countries, cultures and languages. This interview was conducted in perfect Spanish!

What inspired you to become a scientist?

It wasn’t so complicated: I was terrible at music, sports, dancing and some other things. My mother dedicated her career to education, so she always encouraged me to study. She’s a physicist. Fortunately, I was very skilled at Chemistry and Biology when I was at school. I never expected to become a scientist though. I thought I would end up studying something related to healthcare and become a health technician or a board member of some sort. I slowly gained interest in diseases – I wanted to understand how disease happens. I got a fellowship when I turned 25 years old, to do a PhD, and I think that’s when it was clear to me that I would become a scientist. I didn’t think this would be a full-time job. I thought people did this as part-time while their main profession was teaching or technical work. I studied Biochemistry as an undergraduate degree – I am from a small town near Porto. I did my MSc in Forensic and Clinical Toxicology – there was a boom for interest in this career because of all the TV shows focusing on crimes! And then, a year after I began my MSc, I got a PhD fellowship focusing on Microbiology – especially pathogen biofilms. I did half of my PhD in Portugal, and half of it in Richmond, Virginia, USA. This is where I first got exposed to the experience of working and living abroad. When I finished my PhD, I applied to postdoc positions in Portugal still, but I didn’t get any fellowships. So I started submitting my CVs abroad, and at that time, I wanted to marry my girlfriend (now my wife), and wanted a stable job. All the opportunities that arose in Europe were for 6 months, or 1 year, or 2 at most. Then I got an offer in the USA for 3 years, but I didn’t get the position, and then I got an offer from Ecuador, from Universidad de San Francisco. Around that time, Spain and Ecuador had links called the Prometeo Program, allowing exchanges between both countries, so it wasn’t uncommon to be able to come to Ecuador. I joined the University under a contract – they were very helpful and handled everything. I was hired as a lecturer and as a researcher. I think it’s good because I keep up to date with education and science, and the future generation of scientists.

You have a career-long involvement in biofilms and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

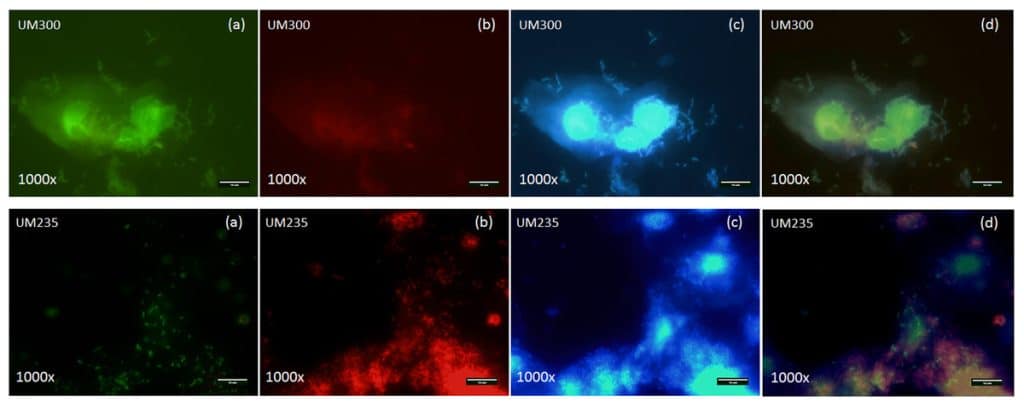

My first contact with microscopy was during my Bachelors, but because I had so many classes, I didn’t find it so exciting nor fell in love with it as a discipline. My love for microscopy is linked to my work in Microbiology – once I entered this field during my PhD, I started using FISH for the diagnostics of some diseases. I worked with fluorescence microscopy for over 4 years at that point and fell in love with it. I still use it as an important part of my work.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a researcher at Universidad de San Francisco de Quito?

The academic system is very different to the Portuguese education system. The system here is liberal arts style – you can start a degree and do Minors in other areas. Lately, since I have children, my routine starts very early. I wake up at 5am, I prepare things, take a shower, wait for my children to wake up, take my daughter to daycare, and then go to the university. At work, I prepare my classes, write grants, do research, supervise students, etc. There’s always something to do. Research is what takes up the majority of my time though. I can now speak Spanish very well – but when I arrived I didn’t, so it was complicated to prepare classes, teach and write in Spanish. My wife is Cuban, but we used to speak in English before. She taught me Spanish and has been very helpful in this journey altogether. It’s funny in my classes, that I’m a Portuguese person speaking with a Cuban accent.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Ecuador?

Not as much, but it’s mostly my fault. When I arrived to Ecuador, I was too busy re-settling and trying to adapt to the new culture, learn the new language, write proposals for the University, and only when I had all that sorted, I started looking for collaborations. First I did so within Ecuador, and only 2 years ago I started trying to expand my network to other countries in the region.

Who are your scientific role models (both Ecuadorian and foreign)?

I have many. In my family I am a ‘first generation’ scientist. My sister is an architect, my father is a tradesman, my grandfather was a construction worker, so no one in my family was a scientist. So I had to look for role models elsewhere. Many teachers at University were my advisers, especially those that taught the hardest subjects. My PhD advisor was barely 5 years older than me, so we had a more brotherly relationship in a way. He taught me, and at the same time he was still learning many things. The director of the institute I joined was also very kind with his comments and suggestions and sharing experience. I think everything he suggested or criticized, he was always right.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Ecuador, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

It’s a trendy topic – I just received a poll on the same topic earlier this week, and it’s a topic addressed now in conferences world-wide. My answer is always the same: it depends on the area. In my area, in Biological Sciences, in the Faculty where I am, the majority of scientists are women. So I don’t think we can generalize. There’s no misbalance in terms of publications, productivity or salaries as far as I know. But if we compare the ratio of men to women with other Faculties, like Engineering, Computer Science, Physics, Mathematics, Economics, I’m sure there is a huge gender gap. I never know how to answer this question, because in my career, the majority of my colleagues are women. In other matters beyond men to women ratio, I think women are at a disadvantage still in that for cultural reasons, women are still seen as the one with greater care-taker duties, towards children or other members of the family. So for instance, motherhood becomes a professional disadvantage still.

What are major differences between performing research in Ecuador and Portugal?

The pace is very different. In Portugal, things were more efficient. Here in Ecuador, things go at a slower pace, firstly because there aren’t many people per group. Basic research is favoured, over applied research. I had to change my mindset and the scientific questions I address, in order to be able to thrive here.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner working in Ecuador?

The language was my biggest challenge at first. It wasn’t the worse case scenario though: Portuguese and Spanish are very similar languages. Also, how to relate to people was a challenge: each culture is different, so there’s a lot of non-spoken things that one has to learn. I had to learn how to speak, how to report things, how to propose things, how to negotiate. And this is done differently from culture to culture. Another challenge was that I went directly from being a PhD student to becoming a PI- I skipped the postdoc phase completely. Luckily, the director of the institute was a somewhat fatherly mentor and thanks to him this transition was easier. He was very supportive during my transition into becoming a PI. I’ve now been a PI since 2014 – 9 years now. It took me one year after arriving, to be able to start doing research, and it took me 3 years to start publishing my research. But I feel I’m still getting started, there’s much to still do.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

My PhD was all in FISH, so I love this. I think confocal microscopy and cytometry are also very valuable methods. I’m also working with EM – SEM and TEM, something I didn’t get a chance to do during my PhD, and I think they’re extremely valuable tools.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

What has most fascinated me has been the evaluation of biofilms by adding bacterial cells to a mucosal cell line I was studying. It was the first time I saw pathogens adhering to the mucosa in real time. The second most extraordinary thing was a 3D reconstruction of a structure from confocal microscopy. It wasn’t part of my paper – I was helping a postdoc with his work, but it was fascinating for me to see this 3D reconstruction.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Ecuadorian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Do what I didn’t – I didn’t have the chance nor did I know this would be valuable: do an internship. This is a great way to find what you’re passionate about, without all the responsibility that comes together with an official degree. You have an opportunity to learn from other scientists, and work in multiple techniques including microscopy. It’s a great way to learn from basic mistakes, to help in a project, and to get a broad view of the research world. Start detaching from books and slowly gain practical experience as early as you can.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Ecuador, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think it’s similar to other countries. Science is becoming more global – people are no longer doing local research, or with local implications alone. Thanks to technology like the Internet and Zoom, the direction of science is diversity in backgrounds: interdisciplinarity, etc. It’s easier and more practical. At the moment for example, one of my MSc students is evaluating drug compounds made in Italy. I think the future of Ecuador is linked to its capacity for international collaborations too.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Ecuador a special place to visit? And Portugal?

Ecuador is a very diverse country. It’s different to read it in a book or hear it in the news or a documentary. It’s something else to arrive in the country and see this with your own eyes. There’s an enormous diversity: of landscapes, of gastronomy, of ecosystems, of ethnicities, etc. On the other hand, what I miss most about Portugal, is our social convivence – it’s not uncommon to finish work at 6pm or so, and then grab a coffee – happy hour is not such a big thing, but a coffee break together is. I miss this.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)