An interview with Eugenia del Pino

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 1 August 2023

MiniBio: Prof. Eugenia del Pino began her career in Ecuador studying to become a science teacher. Later, she was awarded two prestigious scholarships that allowed her to do her postgraduate studies in the USA. She first did her Master’s Degree at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York already focusing in cell biology. She then did her PhD in developmental biology at Emory University, under the supervision of Prof. Alan Humphries. After concluding her studied in the USA, she returned to Ecuador, and contributed to many initiatives aimed at promoting the advancement of science and technology in her country. She is known for her work about early development of frogs and is a developmental biology pioneer in Ecuador. Eugenia is one of the founders of the National Academy of Sciences of Ecuador, and for over 25 years, she was involved in conservation programs for the Galapagos Islands, including serving as vice – president of the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galapagos Islands. She has participated in international exchanges and is an awardee of prestigious recognitions. She has blazed the trail for younger generations of scientists working on developmental biology and conservation, many of whom now are leaders of various research fields both in Ecuador and abroad. You can read more about her career in these issues: https://ijdb.ehu.eus/article/190351ed, https://ijdb.ehu.eus/article/200104ed

What inspired you to become a scientist?

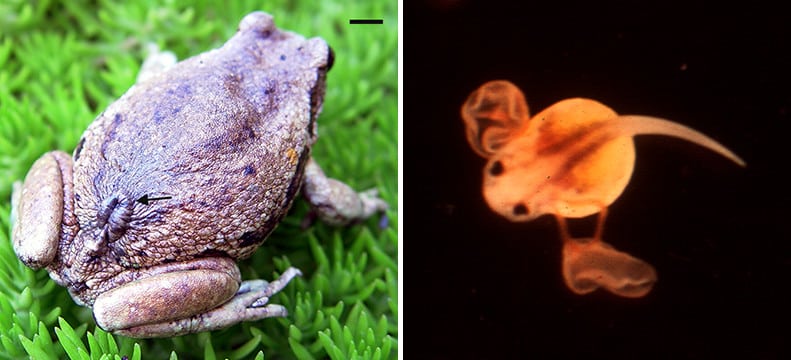

I was a bright student, and did well in school. I loved all of the subjects, so choosing a career became very difficult. I kept wondering – what if I make the wrong choice and end up regretting it? One of my brothers convinced me that not studying was not an option, because our parents would not live forever, and I needed a career to be able to make a living. I entered the School of Education of Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador to become a high school teacher (in what follows, I will refer to this university as PUCE). It was a degree program of 4 years. In this way, I got a degree that allowed me to teach, although I did not specifically want to be a high school teacher. At this point, there was a program called “Alianza para el Progreso” created by the USA government of President John F. Kennedy. One of the purposes of this program was to improve the teaching of science in Ecuador and other Latin American countries. Support was provided for the training of teachers at several universities. The aim was the training of science teachers that after completion of their studies would teach science in schools throughout the country. When I entered the PUCE, I found that there were foreign teachers and equipment, including microscopes and other laboratory pieces to train us, and I found this fascinating. I loved it. The Director of Biology, Dr. Candida Acosta, was actively seeking candidates who would qualify to enter Master’s Degree programs at universities in the USA. Her idea was that by the end of the “Alianza para el Progreso” program, these students could replace the foreign faculty. The Latin American Scholarship Program of American Universities awarded me a scholarship and it allowed me to study for 4 years in the USA. I then got another year’s worth of funding from the American Association of University Women. Both programs combined allowed me to finish the PhD. I had a moral commitment to come back to my country at the completion of my studies abroad. I always received a wonderful treatment, and valued the opportunities I had been given, I was grateful, and so returning to Ecuador was my only option. I thought that if you return to a Latin America country to pay back a scholarship and you wish to go back later to the USA it would become impossible to continue your research. Science advances very quickly and you would be far behind. At least that is how I saw it. So I returned to Ecuador with a clear mindset that the rest of my career would be in Ecuador and not elsewhere. In my career, there were two turning points: The first one was my teaching assignment at the Guayaquil State University (Universidad Estatal de Guayaquil). I did not know what was considered an advanced level in Guayaquil. I was just coming back from finishing my PhD. Therefore; I worked day and night to prepare my two – hour daily lectures. I never had a group of students who were more fascinated about the work that I presented. It conquered my heart – I realized that I could dedicate myself to teaching in Ecuador. My surprise came at the end of the course. I had to give an exam. Upon marking the tests, I realized that the students had not understood much of what I taught. One of the students told me that there was fascination in my enthusiasm and passion for science. These words stayed with me forever. When I found a position at PUCE in Quito, I knew that teaching was my option. On the other hand, I was very lucky: I got a full time position at PUCE. Around this time, professors were paid by the hour – so, for example, you would be assigned 5 hours of teaching per week and be paid accordingly. However, my position was full time with a better salary. Of course, the workload was also very high, and I had administrative duties. I realized that if I were a full professor at a university in the USA, I would have had teaching duties, but I would also have a research group; I would lead a lab that would allow us to pursue our scientific questions. I wanted to do a career in Ecuador that would include teaching and research and I needed to find a way to do so. The second turning point came with the establishment of my research niche, I came across a frog with a reproduction strategy that resembles the mammals, and it was completely different to any other frog used in labs focusing on developmental biology. This frog is Gastrotheca, the marsupial frog from the gardens of Quito. I wanted to ask questions, which would allow me to do unique and original research. I also decided that I would make the utmost effort to publish my group’s findings, and to do so in the best journals. This was my career’s strategy. To answer your question on what inspired me to become a scientist: the answer is serendipity. By serendipity, I started my studies when the program “Alianza para el Progreso” had started. When it comes to the establishment of my research niche, it was also serendipity: I was walking in the PUCE gardens and came across this unique frog. In addition, it was by serendipity that I became a Biologist and not a Linguist (despite the fact that I also love languages).

You have a career-long involvement in developmental biology, and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

We are talking about an era prior to the emergence of molecular, biology as a discipline in graduate schools, and for this reason; molecular biology was not among my options. I wish to add that I was never interested in Ecology – I am not a field researcher, despite having worked in the Galapagos Islands. I loved cytology and biochemistry.

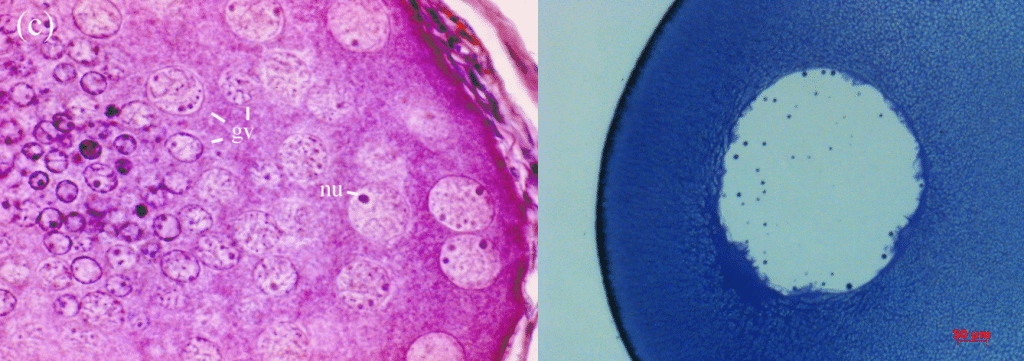

I became interested in frog oogenesis and development also by serendipity: for my Master’s Degree in the USA, I studied at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. My research dealt with the biology of free – living protozoans. My advisor recommended that I apply to the PhD program in Biology at Emory University to work with an expert in free – living protozoans. Little did I know that this PI was an ecologist, and the proposal he gave me, for the PhD project, involved studying protozoans collected from the grasses of a riverbank. I would have had to collect these particular grasses with its protozoan inhabitants. Upon hearing this, I knew that this project was definitely not for me, as I do not consider myself qualified for fieldwork. Therefore, I searched other research options, and eventually I joined the lab of Prof. Alan Humphries, Jr., who was working with the oocytes of salamanders and of the frog Xenopus. At the time, oogenesis was a hugely important topic – it still is super significant, but now it is less of a trendy topic. I asked him if I could join his lab. I was very lucky, as he agreed. Many years later, I asked Prof. Humphries whether he hesitated to take me as his PhD student, and he said yes. He said that accepting me brought him in conflict with the other powerful colleague (whose lab I had chosen not to join). However, both professors were very generous, and I had a lot of intellectual freedom during my studies. My interest in frog development derives from my graduate work. I was not interested in the frogs per se, but rather, in understanding oogenesis and using frog oocytes (immature ovules) for this purpose. Frog oocytes have an enormous nucleus, which can be observed using microscopes. After my return to Ecuador, I wanted to continue with the analysis of frog oogenesis. Due to the lack of resources to buy specimens of the frog Xenopus, I searched for a local frog. I thought, naively, that all frogs were equivalent, and that any frog would do. However, as I found out, each frog is unique, especially with so many exciting adaptations happening during evolution in the tropics. Little by little, I have learned more about Ecology and my respect for nature has continued to grow. In summary, I didn’t go out as a field researcher in pursuit of a frog. However, I do love nature.

Regarding microscopy, Alan Humphries’ lab focused on cytology and other techniques. We aimed to study frog oocytes and the process of fertilization, which required several types of microscopes, including a dissection microscope to extract the oocyte nucleus. We would then use other techniques including phase contrast and in situ hybridization using radioactive probes. Therefore, it has been a fantastic voyage into microscopy, guided by my interest in oogenesis and fertilization.

Moreover, you were the founder of many of these disciplines in Ecuador. Can you tell us how this came to happen, and what were memorable experiences from this process?

I had freedom in my career to propose and pursue different initiatives (again serendipity playing a role in this). I am lucky. My colleagues and I at the PUCE School of Biological Sciences contributed to establish biology as an academic discipline in Ecuador, and to the scientific advancement of our country for over 50 years. This makes us very happy. We have seen younger generations of scientists who have gone abroad to study, and have then returned, and are a part of Ecuador’s research development. They are tirelessly working to advance Ecuador’s scientific progress. The same is true for those who studied and remained abroad. This is part of the brain drain that Latin America has experienced. I think your blog is highlighting this point in fact: Latin America has many brilliant scientists, very capable, and in many cases, there are no possibilities to develop their careers in their own countries. Why are there no possibilities? Because of the lack of funding, the scarcity of research positions, and because some think that a scientific career would be easier to build somewhere else, where funds are not as restricted.

You also founded the National Academy of Sciences of Ecuador, and have led efforts to the conservation of the Galapagos Archipelago, including being the vice president of the Charles Darwin Foundation. Can you tell us how these initiatives came into place, and the effect this has had in Ecuador?

These initiatives were all developed with the aim to contribute to society. The National Academy of Sciences of Ecuador was one of them. I share the merit with the other Founding Members that tireless worked in drafting the Statutes and obtaining the approval of our government. At TWAS meetings (The World Academy of Sciences for the advancement of Science in Developing Countries), my international colleagues would remark that Ecuador did not have a National Academy of Sciences, and asked me to consider fostering the foundation of our academy of sciences. Back in Ecuador, I tried more than once – I spoke with administrators at the government level without results. Around this time, my colleague Santiago Ron was invited to a meeting in London, and he received the same suggestion, the establishment of the National Academy of Sciences. He came back and told me about this interest. I offered him my support, and we joined forces to pursue this goal. We needed a group of Founding Members who could meet regularly to discuss and advance in the establishment of the academy. Therefore, I invited some colleagues from the PUCE School of Biological Sciences, and that is how it all started. There was an unusual coincidence, another case of serendipity: At this point, and to my surprise, the authorities regulating Science and Technology in Ecuador (SENESCYT) were in fact interested in the establishment of the National Academy of Sciences of Ecuador. Once they knew about our work, we received the official support, and our efforts led to the creation of the “Fundación Academia de Ciencias del Ecuador” (The official category is a “foundation”). Despite the inherent difficulties of a young academy of sciences, this organization is up and running and Ecuador is no longer one of the few countries without a National Academy of Sciences in Latin America. An academy of sciences is important to provide honor and recognition. Scientists need the recognition from society, and the science academies provide this kind of support. Besides, the academies of science provide international contacts of value for the country, and can be a source of advice to the government on scientific matters. Returning to the time when we started, I just wanted to initiate a sort of “chemical reaction” – we had the substrate, we needed an enzyme to act as a catalyzer, which, once the job was completed, was free to leave. I wanted to trigger this chain reaction and then be able to come back to my research in frog development.

Regarding Galapagos research, and my election as vice-president of the Charles Darwin Foundation, there was again an aspect of serendipity. In the early years of my work at PUCE, I had to guide the research projects of many of our undergraduate students, a requirement for their BSc degrees. We do not have a PhD program, but in order to complete a BSc degree from PUCE, students have to write a thesis. I had the responsibility of finding research projects for a huge number of students who wrote individual theses based on original research. The contact with science in the Galapagos helped me, as it provided research possibilities for the training of our students. The Director of the Charles Darwin Foundation for the Galapagos Islands, Dr. Peter Kramer, visited us. He thought that scientists in the Galapagos Islands could guide the research of undergraduates from Ecuadorian universities, and for this purpose, he established a scholarship program. The work conducted by students in the Galapagos Islands could fulfill the BSc thesis requirements. I gave support to this scholarship program by sending my brightest students to the Galapagos Islands. Through the years, this fellowship program has contributed to the training of numerous students from different universities in Ecuador, but we, at PUCE, were the first to recognize the importance of this program for Ecuador. Students came back with notebooks full of data, which I then had to interpret in order to help them with the writing of their theses. Dr. Kramer was pleased with my collaboration and considered that it would be ideal if I joined the scientists and students during the fieldwork, to see firsthand what they were doing and in this way be better prepared to help with thesis writing. I visited the Galapagos Islands on many occasions to see the ongoing research of several students. We published the results mostly in Ecuadorian journals. Due to this connection, I became an expert in the biology and biodiversity of the Galapagos Archipelago – the place that conquered my heart. My contribution was teaching, in the context of conservation of the Galapagos Archipelago. I served as vice-president for Ecuador of the Charles Darwin Foundation for four years. I recognized that this position involved lobbying for conservation of the Galapagos Islands. A task that demanded a lot of time. I realized that I could not dedicate the time required and so I stepped down and did not wish to be re-elected. Overall, I contributed to Galapagos conservation for 25 years. This does not mean that my interest in conservation of the Galapagos has faded – on the contrary. Moreover, because of these efforts, over the years, many of my students have become outstanding ecologists both in Ecuador and in Latin America. I think this is not a minor achievement.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Ecuador, from your education years?

From the beginning of my studies, until I finished high school, I attended a catholic private school led by nuns. I was a good student, and I did not face intellectual challenges. The school promoted order and discipline – I was neither. As a result, each year, I received all the medals with exception of the discipline medal. I am very grateful for an education that allowed me to develop both of these traits. They are very important for life and have been key for my career too. The teaching was theoretical and came from books without laboratory practices; I did not receive lab instruction in elementary or high school. Therefore, my first contact with a microscope occurred at PUCE, thanks to the equipment donated by the program “Alianza para el Progreso”. I think those are the key points of my early training. A number of circumstances allowed my becoming a researcher in Ecuador.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Ecuador?

Yes. When I started to work at PUCE, a program of the UN, the PNUD (Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo), awarded fellowships and research funds to scientists from the Andean Countries. Initially, it offered very small grants (2000 USD) for biological and biochemical research in countries of the Andean region (Ecuador, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia). I got some of these grants. At some point, the programs became binational or trinational. For a binational program, scientists from a country with less research development paired up with investigators from a country with more advanced research. I received a binational grant together with Dr. Marcelo Cabada, who worked in Prof. Francisco Barbieri’s lab at Universidad Nacional de Tucuman, Argentina. Marcelo came to Quito and I and some of my students visited Tucuman. Marcelo and his coworkers helped us with EM analyses of frog ovules. These images waited in my drawer for nearly 40 years, until I incorporated them in a monograph about the Hemiphractid frogs, written in collaboration with several authors (marsupial frogs belong to the family Hemiphractidae). I learned key things during the binational project in particular to be resourceful: for example, in order to separate the egg yolk, we needed specific filters. Our collaborators in Tucuman used several layers of women’s tights, which apparently worked wonderfully as filters. In addition, small containers for frog oocytes came from used blisters from medicines. For this purpose, my Argentinian colleagues had a drawer full of used blisters. Fifteen years after these events, I lived a similar experience in Germany. I was awarded an Alexander von Humboldt fellowship for a sabbatical. I spent a year at DKFZ in Heidelberg (German Cancer Research Center). I was also collaborating with a Developmental Biology lab at the Max Plank Institute in Tübingen. My friends from Tübingen invited me to see how oocytes could be embedded in a new paraffin they had designed, for performing fluorescence microscopy. They needed containers to do these experiments and to my surprise, they were also using the medicine blister packs. The difference with my Argentinian colleagues was that the blisters in Germany were brand new, due to a partnership with a local factory. They gave me a few of those and I brought them back to Ecuador. To answer your question, the main Latin Americans I have interacted with throughout my career have been Argentinians, and I quickly realized that the level of scientific research they were able to perform was well above the one we could perform in Ecuador back in 1975. I also had the chance to work with Chilean colleagues. Dr. Jorge Allende organized a workshop on molecular biology in his lab at the University of Chile in Santiago. This was back in 1977, and I was able to see their biochemistry lab. Foreign experts came to this workshop.. Throughout my career, I have been able to interact with several Chilean colleagues, and they were very polite – it was wonderful to work with them. I have been well received in Mexico and I appreciate the wonderful science done in Mexico. There is unity in Latin America – as we share the same language (or almost), and we share many cultural traits, but each country is still very unique.

Who are your scientific role models (both Ecuadorian and foreign)?

I thought about this question a lot. My main role model has been Dr. Asa Alan Humphries, Jr. – my PhD supervisor. He was trained in the classical school of biological sciences. He comes from a line of research dating back to Theodore Boveri, who figured out cell division, the importance of meiosis, and the relationship nucleus – cytoplasm in embryonic development. One of his students, Fritz Baltzer, in turn was the professor of Gerhard Fankhauser, who got a job at Princeton University in the USA. He was the PhD advisor of Alan Humphries. I am reading the biography of Boveri – I have read it before – he was a very interesting person. He took care that his students make adequate observations of the biological specimens – he supervised closely and really wanted his students to succeed. I think this is transmitted across the generations of scientists working together. This is what I experienced with Alan Humphries. In addition, this is what I tried to maintain with my students too, as a leader myself. We would take coffee breaks and either I would present an idea, or my students would tell me theirs, I learned all this from my mentor.

You trained many of the new generation of scientists. How does this make you feel?

It is their achievement rather than mine. I am very proud of all of them. As I mentioned earlier, in Ecuador we do not have postgraduate courses (i.e. PhDs), so whatever I taught them, was early in their careers. Their successes are of course also shared successes for the country – they represent, Ecuador, at home and abroad and this benefits Ecuadorian science.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Ecuador, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

As a young student in Quito, I attended an only – girls school. Later, Vassar College was also just for women, now it is a co – ed institution. The philosophy that I experienced is that as a woman, you could achieve anything you set your mind to. Gender was never a reason to limit one’s dreams; this made me a strong woman. I developed a personality, which allows me to thrive and defend my values, and opinions while at the same time being polite. I do not know whether I have ever faced a pay gap related to my gender because salaries were not made public. For me, it was important to have a job, and to succeed in my work. When I stared to work at PUCE, I paid attention to the number of female and male faculty. Back then, the biology faculty had more women than men. Men were more dominant in the faculties of Law, Engineering, and Economics I see that the ratios have changed a lot: there are many women as students, but very few women reach leading roles. I think this is a global issue, rather than something specific to Ecuador.

Are there any historical events in Ecuador that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

When I came back from the USA in 1972, Ecuador was under a military dictatorship. Our dictatorship was mild in comparison with those of Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina. I was in Chile at the time of Augusto Pinochet’s regime, for the 1977 – course that I mentioned. We were in a big auditorium, and a large international community was attending the lectures. In the back of the auditorium, there were “unknown” people – likely government agents – who were monitoring the gathering. I visited Argentina in 1978 (a time when Argentina was under a dictatorship – El Proceso). I was visiting in Tucuman for a congress – it surprised me that there were circulation restrictions near the military installations. Oil exploitation began during our dictatorship and this was a major event for the advancement to the 20th century level. The country changed; there were better schools, better roads, and improvement in the life standards of the population. Years later, the Ministry of Science and Technology was developed. It is a beneficial institution, and it provides grants to support scientific work. It established a program of fellowships to allow young Ecuadorians to study abroad. I think that the next step to promote science should be to support PhD programs within Ecuador, rather than favoring the brain – drain, or causing the unfortunate situation of young scientists coming back from their time abroad to realize that their expertise cannot be put to use due to lack of resources in their own country. The scientific potential of Ecuador has not been reached. There is plenty to be done. In Ecuador, there is work in applied science, but not much in basic research. Basic science is a luxury that developing countries cannot afford. Let us hope this improves with time to have better research facilities and more vacancies for our young generations of scientists. Politics in Ecuador have been unstable, but science managed to prevail despite the challenges.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Ecuador?

I was always welcome everywhere I went. When I was in the USA, I had to use the language with high proficiency in order to be able to communicate, and the year I spent in Germany, I enjoyed speaking in German. Altogether, I would not say I faced challenges. People were very kind – the international community has always been very generous and kind with me.

What is your favorite type of microscopy and why?

In my work, I used traditional methods of cytology – so I used dissection microscopes, epifluorescence microscopes, DIC, confocal microscopy, and EM – TEM. In Quito too, I was able to do DIC. I find both DIC and confocal microscopy fascinating. Although I haven’t done it, super resolution microscopy methods to see single molecules sounds like a fascinating achievement. It all depends on the scientific questions you are asking though. The advances in biology go hand in hand with advances in physics, and microscopy is one of such examples.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

It was seeing multi-nucleated oocytes. I came up with the term multi-nucleated oogenesis. Ovules come from immature cells called oocytes or ovocytes. Each oocyte is as an individual cell and has only one nucleus. The oocyte nucleus is huge. To my surprise, I discovered that in some frogs, oocytes have up to hundreds to thousands of nuclei instead of just one single nucleus. I dissected an oocyte of Flectonotus, a Venezuelan frog, and to my surprise, I saw a large number of spherical, semi-transparent structures – we determined that they were nuclei. Multi-nucleated oogenesis can be compared with oogenesis in the fruit fly Drosophila. Oocytes in Drosophila are connected through channels, with sister cells. In our case, I think all of the nuclei of a Flectonotus oocyte might derive from sister nuclei of the oocyte nucleus, following a comparable pattern with Drosophila. Therefore, to see, the many nuclei of a live, multi – nucleated oocyte was something wonderful. I wanted to dedicate my career to study this phenomenon. Sadly, frogs with multinucleated – oocytes are difficult to obtain, so after a few years I had to switch my research line. I re – focused my interests to frog embryonic development.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Ecuadorian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Future scientists in Ecuador and elsewhere should know that in life we could not have everything. Therefore, the most important piece of advice is to recognize this limitation and to do realistic choices in our job and research endeavors. Whenever you face an obstacle, you will have to find a way around it. You cannot stop doing research simply because you do not have a confocal microscope. Although the resources are scarce in Ecuador compared to other countries, we do have a lot, and you have to ask questions, unique to your environment, to your field, and to your possibilities.

It is important to have a job that allows you to develop a research project. Once you have job, a) dedicate a lot of effort to pursue your aims and to investigate your scientific questions, and b) set yourself goals that you can achieve. Once you have results, write a scientific report of enough quality to be published in a journal with international standards. If you publish in an unrecognized journal, you will not be competitive, and you will not be able to obtain local or international grants. Be disciplined in your work. In addition, as per the point above, make the most of the resources that you do have. Do the best possible work that you can do, with the equipment and materials available, and be original in the work that you do.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Ecuador, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

The future of science in Ecuador? I have lived in a small world – in my lab and in my faculty. I do not think I can give an account of how science is advancing in the country. It would be wonderful if basic science could get more support. So that scientists could develop their own ideas, no matter what those ideas are – rather than forcing all of their work towards scientific applications. I think this is vital for the scientific advancement of every country.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Ecuador a special place to visit?

Ecuador has a rich geography, and a huge biodiversity. It is one of the mega – diverse countries of the world. This feature is super attractive to visitors, especially scientists. For example, we have over 600 species of frogs. Only Colombia and Brazil have a higher number of frog species – but both are bigger countries. Therefore, the concentration of species is huge in Ecuador. Ecuadorians have a different character based on geography and are mostly divided into the peoples living in the highlands and those living in the lowlands where you will find a tropical environment. Still, what makes us similar is that we welcome visitors. Gastronomy is very good – we can prepare a soup of everything and anything, and our “encebollado” is now recognized as the second best fish soup in the world (according to a ranking of the gastronomic page Taste Atlas, published on June 28, 2023).

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)