An interview with Mario Del Rosario

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 22 August 2023

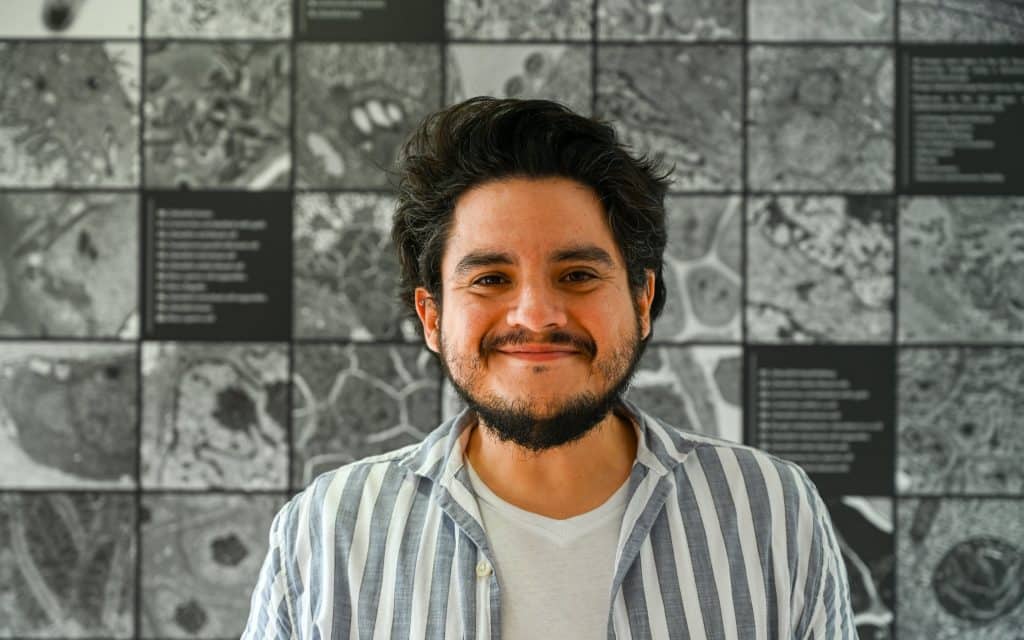

MiniBio: Dr. Mario Del Rosario is currently a postdoctoral scientist in the lab of Prof. Ricardo Henriques at Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciencias, in Oeiras, Portugal. Mario completed his undergraduate studies at Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral, where he studied for a BSc in Biology. He then did a Masters in Research in Biomedical Sciences at the University of Glasgow, in Scotland, where he focused on the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, and how infection into macrophages occurs. He stayed in the same lab for his PhD, which he completed in 2019. During this time, he learned and developed super-resolution microscopy tools to study Toxoplasma gondii -host cell interactions, especially, actin dynamics and invasion kinetics. In December 2020, he joined IGC, where he contributes to the efforts of the Henriques lab to democratize microscopy, and focuses on using Machine Learning and image analysis to study phototoxicity, and super-resolution microscopy to study parasites and viruses.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I had 3 sources of inspiration. I feel one pushed me to study science, one to study Biology, and one to specialize in host-pathogen interactions. Since I was a child, I would easily get obsessed with things. In Ecuador, we have the ‘El Niño’ phenomenon, and one particular year we suffered many floodings throughout the country. In my city, Guayaquil, there were many areas that were underwater, and frogs started to increase in numbers. They caught my attention – I would see frogs and many tadpoles and I was very intrigued with them. I thought tadpoles were fish at first. I couldn’t understand the link between these “fish”, the frogs, and where the frogs were coming from. I eventually found a book explaining frog developmental cycles answering some of my questions but I was still not satisfied. I spent the following day capturing tadpoles and bringing them home to observe them in a terrarium. I saw that the majority were dying, and just a few would develop and start growing legs. When I returned to the place I found them originally, the majority were developing very well. I wondered about the differences: why did the frogs that I brought home with me were suffering and dying, and those in their natural environment were surviving? Although the answer was very obvious, this led me to read a lot about frog biology and to understand and become familiar with the scientific method. This experience led me to wonder how we change the world around us as we try to observe it. This has been a recurrent topic in my research up to this day. The second source of inspiration happened during early high school. I saw a bacteriophage EM image in a book, and when I observed it, my understanding of how Biology works suddenly went out of rails. I always imagined cells as having organelles and more rounded shapes, but a bacteriophage is just a group of proteins and genetic material with beautiful geometric shapes. This triggered my curiosity to understand how protein aggregation could result in the formation of geometric forms such as the icosahedral shapes we see in the capsids of certain viruses. This inspiration led me to choose Biology as a degree at University. Finally, my third source of inspiration to focus on microscopy, happened when I started my degree at University. I was studying Marine Biology and my first exposure to microscopy was during one of the practicals. The lab where I did my practicals also offered as a commercial service, the analysis of histological sections of marine organisms (mostly shrimps and fish) for aquaculture farms in Ecuador. One of the aims of my practical was to recognize tissues by histology and determine any pathology or infection these fish and shrimps could carry. I was able to recognize an infected tissue without always being able to see the microorganism that caused the infection – only as a result of recognizing tissue damage caused by the infectious agent. This inspired me to better understand how pathogens work, and how these alter the physiology of other organisms. Around this time, I shifted my focus to better understand human pathogens. For this reason, I decided to do an MSc in Biomedical sciences. Since Ecuador did not have opportunities to do this, I went to the UK to do my MSc. That’s when I started working with pathogens, trying to understand how different infectious diseases can interact with their host.

Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose the various paths you’ve taken during your career?

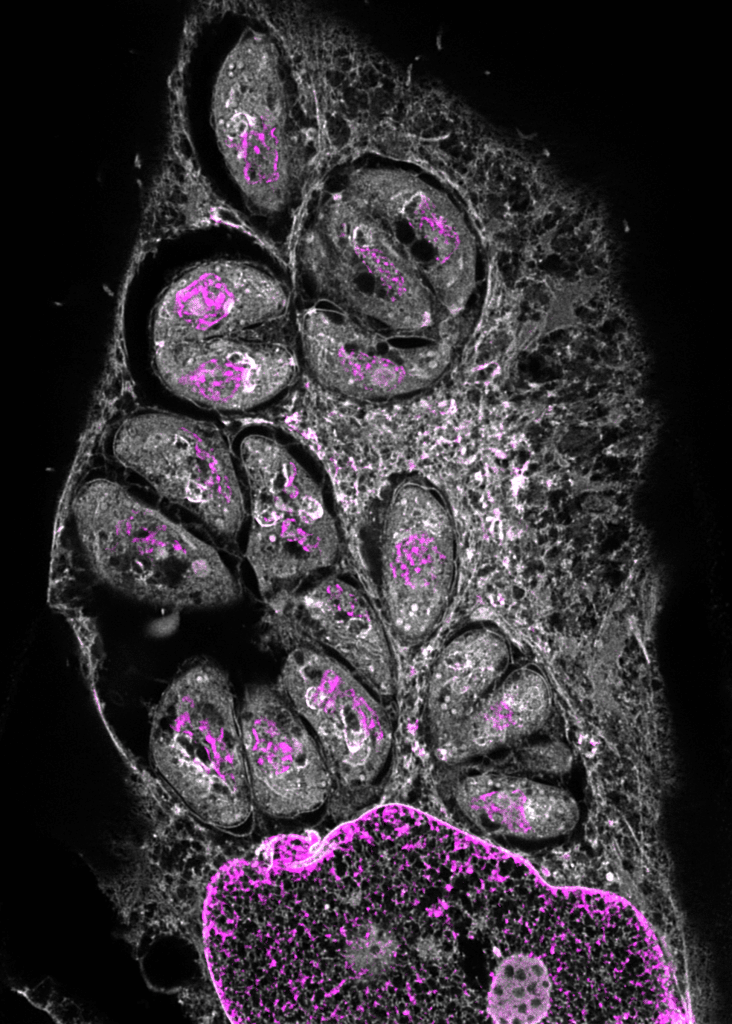

I started my career focusing on Marine Biology, which is something very different to what I do now. My degree was very traditional – very practical and field-oriented- we had to collect samples and analyze them. We could study how different organisms changed with respect to the sun, or the seasons. A topic that always attracted me was microbiology and molecular biology. Adding this to my growing interest in pathology, I decided to study for a master’s in biomedical sciences. Something interesting happened at this point. Originally, my interests were very much in neurosciences and how pathogens can cross the brain-blood barrier to cause infections in the brain. If you do a Master’s in Research under the British system you attend lectures for 2 months, then you do two different projects, one for 6 months, and another for 5. As part of the program, we had to present a poster on a topic that was related to the lectures. I chose to do a poster on how Toxoplasma spp. can traverse the brain-blood barrier, and this was the topic of research of an investigator working at the University of Glasgow, Markus Meissner. I saw that his lab was offering a project for my master’s and decided to join his lab. I focused on how different Toxoplasma strains behave and are taken up by host macrophages and epithelial cells. I loved the mix of tools that my project offered, namely, being able to genetically engineer parasites, and using microscopy to image how these alterations resulted in different pathology within the host. I’m a very visual person, and for me, being able to see, in real-time, how parasites invade cells and how they alter cell physiology, made me fall in love with the topic. I spoke to Markus, and we agreed that I would do my PhD in his lab. I stayed for several years, focusing on mechanisms of parasite invasion. We initially focused on the biophysics of parasite invasion but later shifted to characterizing some of the molecular mechanisms behind it– for instance, how actin dynamics affected invasion and infection outcomes. As a next step I wanted to do a postdoc focusing on malaria, but then the pandemic hit, and I ended up not being able to go there. Around this time, I saw that Ricardo Henriques was looking for postdocs for his lab, which was at the time moving his lab to Portugal. I decided to apply even though my profile didn’t completely fit the requirements of the position. He was looking for virologists with experience in super-resolution. My expertise was in parasitology and super-resolution. Despite not being the ideal candidate, there was a great connection between us. He accepted me in his lab, and I have now been in Portugal working in his team for over 2 years. My focus has completely changed. I feel am no longer 100% a biologist but something in between a biologist and an engineer. I now use biology to study technology! I am still interested in answering biological questions, but since our lab aims to develop novel technology, we use organisms to develop technology that later on allows us to answer our biological questions. Currently, I work with bacteriophages, HIV viruses, parasites and mammalian cells. There are various lines of research in our lab – one of them is to try to model infections in T cells to create smart microscopy that allows us to capture these events for us to study how these cells interact. My new fascination is to understand and quantify how living samples are affected by light during fluorescence live-cell microscopy. We are creating an automated method to study cells – assigning them measurable values based on their behaviour to determine if they are affected by phototoxicity.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Ecuador, from your education years?

I think my experience was very positive. One thing I value a lot from the Ecuadorian system is that, for example, I found the UK system to demand a high level of specialization from the beginning. You start a BSc degree and you immediately choose whether you’ll study Biotechnology or Immunology or Microbiology. In Ecuador, we don’t have that level of specialization, so we can’t have such a focused career from the start. We study Biology in a very broad sense, and I found this to be great because I was able to learn a bit of everything. This allowed me to adapt to many different challenges and requirements that I need for my work. This has opened many doors for me – to be able to participate in many projects and adapt new technologies to each of these projects.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a postdoctoral researcher at Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciencia?

I work with a lot of Engineers, Mathematicians, Physicists, and Computer Scientists. In my day-to-day work, I split my time between doing biological experiments on the bench and also computational work. Generally, I maintain cell cultures which I then use for different projects, mostly involving live-cell microscopy. We are currently creating non-infectious mutants of HIV to study infection dynamics in a controlled manner. I do multiple things that are very versatile, like purifying viral particles, keeping parasite cultures, or maintaining mammalian cells to study phototoxicity. It’s a very interesting postdoc because I never get bored, but from the outside, it might seem to not be very focused. The key point here is that I employ a wide range of biological samples to obtain the best tools I require for my research. I want to use biology (everything and anything), to create technological tools for the community!

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Ecuador?

Yes, mostly when I was in Glasgow and now in Portugal. In Ecuador, I didn’t have a lot of contact with other Latin Americans. But in both, the UK and Portugal, I’ve met many researchers, mostly from Mexico and Brazil.

Who are your scientific role models (both Ecuadorian and foreign)?

My first scientific role model was the person with whom I did my undergraduate studies, Marcelo Muñoz, who taught me and gave me all the basis on how to do scientific research. He inspired me a lot to understand how to do science in general. In Ecuador there are many limitations in terms of technical and human resources – he taught me how to make the most out of these resources to be able to do research. He was my main inspiration, especially at the beginning. Ever since I started my postgraduate career, I admire all researchers who are not Biologists, and who decide to jump into the field of Biology to study new systems. I think leaving one’s ‘natural environment’ or ‘comfort zone’ is difficult and intimidating and I consider it’s brave and commendable to do it. This is of course not restricted to Biology – there are many scientists who do interdisciplinary research, and/or jump from one area to the other during their careers. I try to push myself to do this too. This line of thought made me feel admiration for Ricardo Henriques. I feel he left his comfort zone – he is a physicist who knows a lot about cellular biology! He not only has a huge capacity as a scientist but also as a communicator. He has a huge ability to connect people, as well as research areas and disciplines. Moreover, I admire his philosophy of democratizing science. In line with multidisciplinary researchers, another researcher I greatly admire is my colleague Estibaliz Goméz de Mariscal. Although a mathematician, she has an honest, almost child-like innate curiosity and wonder for biology that serves as an inspiration for an experimentalist like me. Sometimes we view particular biological phenomena as obvious and being presented with basic questions often leads me to formulate new questions and ideas.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Ecuador, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I am happy that in Portugal there is really an attempt to achieve gender balance and to close the gaps between genders. This is something I never saw in Ecuador. My time in Ecuador opened my eyes as to how women in science are perceived, and the unfair treatment that still exists. I was working with female colleagues, and I always felt that say, my opinion, despite not always being accurate, was always listened to and respected while theirs were not. In my lab in Portugal, Ricardo tries to keep the gender balance to 50:50, and I feel people’s opinions are valued regardless of gender or any other characteristics. We are respected as people. This is very refreshing, especially given my previous experiences. Portugal is one of the best places I’ve seen in terms of initiatives and efforts towards gender balance.

Are there any historical events in Ecuador that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

I‘m not very good at history so I’m not the best person to ask. We have a history of epidemics throughout the last two centuries that required the effort of local and foreign scientists to control. Generally speaking, there has always been a foreign influence when it comes to research, especially in the field of infectious diseases.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Ecuador?

Adapting to the different cultures is always a challenge. I don’t feel this challenge is unique to Latin Americans. Every person that goes into new a culture needs to adapt. I’ve always felt very welcome within the scientific community. I know other people might have different experiences, but in my own case, I’ve always felt that people received me with open arms.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

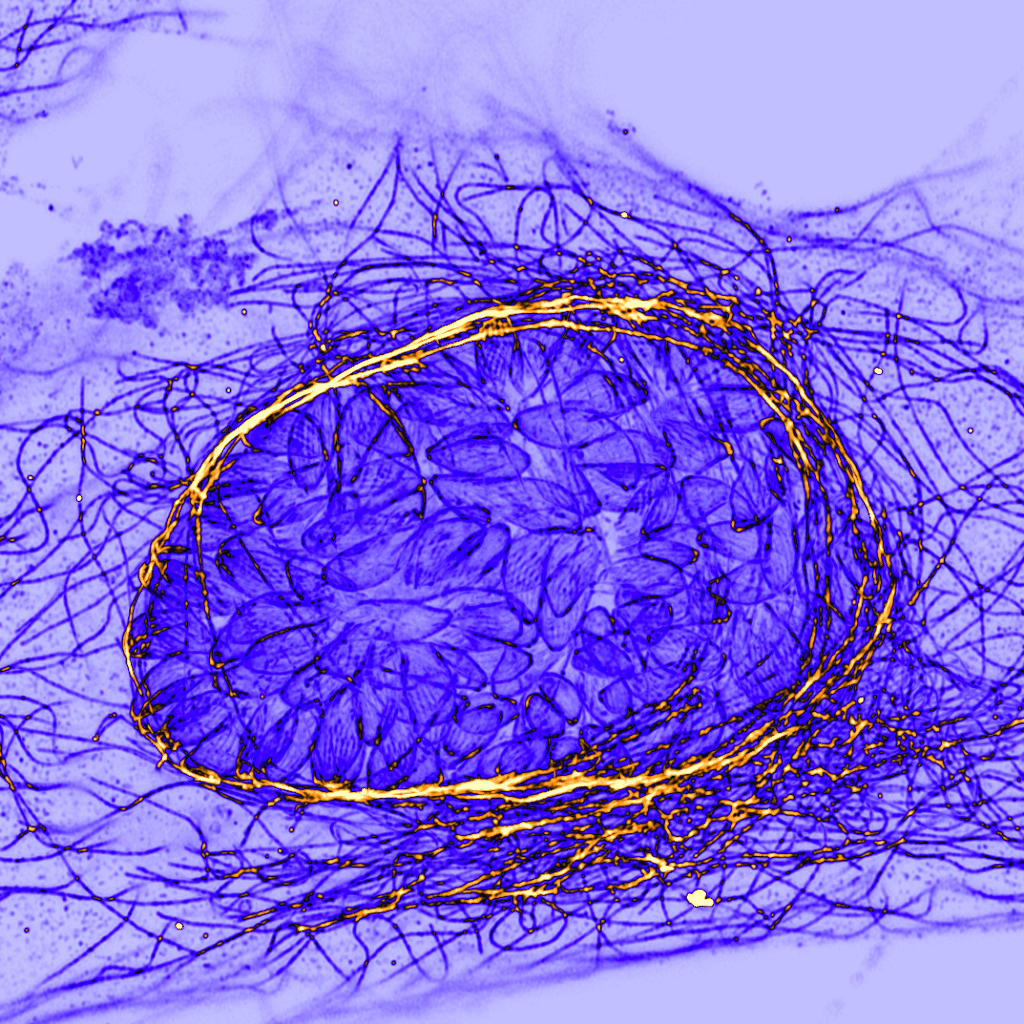

That’s a difficult question. I don’t have a favourite type. I use the type of microscopy that will help me answer my research question in the most efficient and accurate way. Over the years, I’ve done electron microscopy, and lots of light microscopy including widefield, confocal and super-resolution. As for the technology itself, I find super-resolution microscopy exciting. Using this technology, we can overcome the hard limit of the diffraction of light – basically, we overcome physical barriers to be able to observe our samples. Something that I’m currently focusing on is expansion microscopy. You can basically anchor your sample in a hydrogel, and with water, expand the gel. We don’t need better resolution (although it helps!) to see new things, but we enlarge the sample to observe sub-cellular and molecular structures. This is a huge revolution. We use this a lot in the lab to observe interactions between pathogens and hosts. There’s an increasing number of publications using expansion microscopy so this gives you an idea of how relevant it is.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

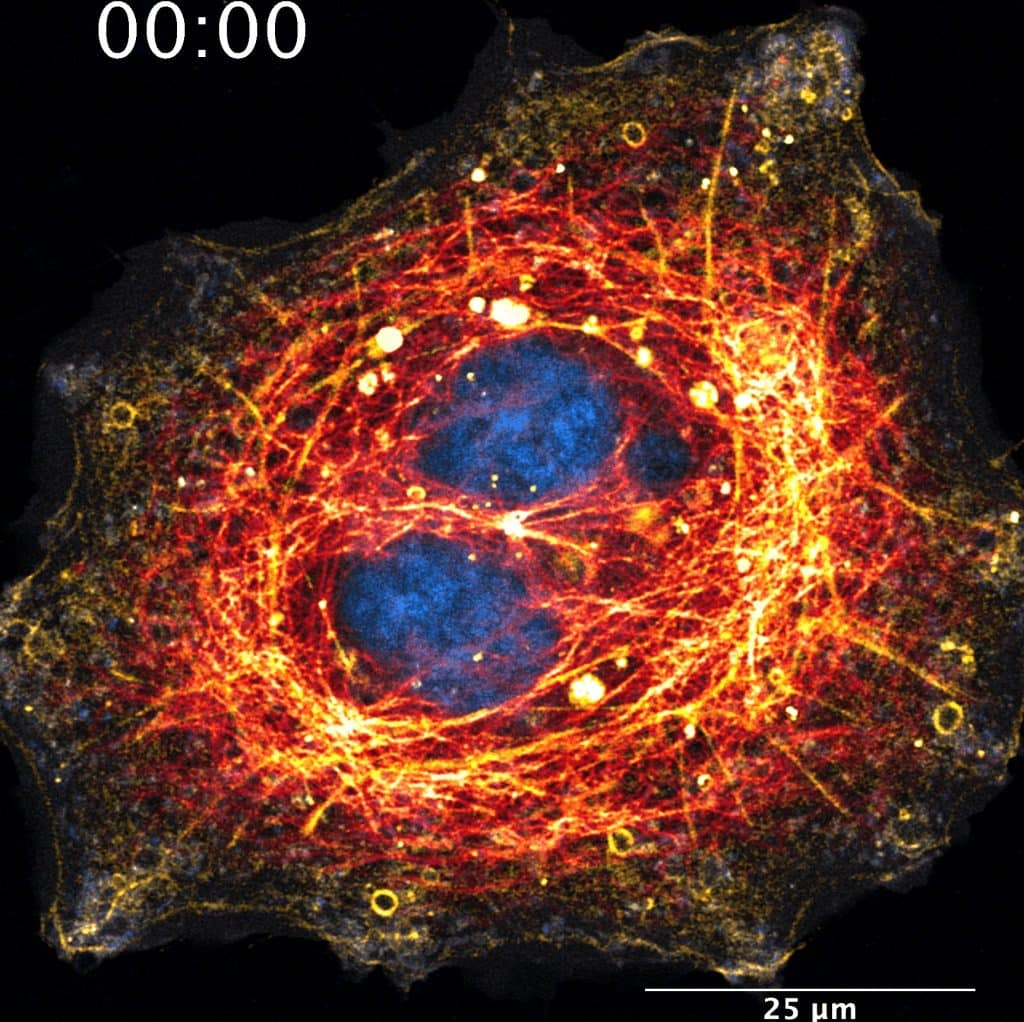

There are two things: one, to be able to see Toxoplasma parasites dividing within host cells – at a point we used nanobodies (llama antibodies that are very small) against actin, to be able to see actin dynamics in vivo. Using fluorescence microscopy, one can see actin dynamics while the parasite divides and it looks almost like an electrical pulse in vivo. The other thing is to do expansion microscopy on mammalian cells, and then use optical microscopy to resolve mitochondria crests. We can resolve this without using electron microscopy or the more cutting-edge super-resolution microscopy techniques.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Ecuadorian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

One of the main points is that we tend to think that because we are in Ecuador and we have less resources than other countries, we will know less, and this is not true. I had to change this mentality when I arrived in the UK. I felt a huge imposter syndrome thinking I would be a ‘lesser’ scientist, but my preparation allowed me to be one of the best students in my class. The lack of resources doesn’t make us worse scientists. Beyond this, I would say, be humble, resilient, perseverant and network a lot! In Ecuador, the landscape for research is a complicated one, and international collaborations are really useful – learn to collaborate and learn to ask for help.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Ecuador, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I strongly believe that microscopy in Ecuador is still ‘in diapers’. The biggest limiting factor is the cost of the equipment. A confocal microscope, for instance, is extremely expensive due to shipping costs and taxes. This is a huge limiting factor for local research! I am very happy to work in Ricardo Henriques’ lab, because the philosophy of the lab is to democratize microscopy technology, including the generation of microscopes. In terms of purchasing power and needs, I consider Latin America would greatly benefit from open-source DIY technology to reduce costs. Commercial equipment is expensive and open-source alternatives are a good option where for example, one could use their own mobile phone’s camera to acquire super-resolution single-molecule data. There are examples of this idea in different stages of implementation so the future is exciting! The computational side is even more accessible at this moment, with a strong movement towards open-access/source for image analysis. Part of my work with Ricardo is to develop these types of Open-Source tools. I hope to eventually contribute to Ecuador in this way. Recently, I was invited to give a talk in Ecuador, and there was already interest in machine learning and image analysis. But there was also a bit of skepticism in that a powerful computer might be needed to do these complex tasks. Luckily, there are tools like ZeroCost, in which we use Google cloud servers to do this process. You don’t need an expensive computer to do anymore. I also feel the mentality of what research is, and its value should change. There are still old-school ways of thinking around. The development of tools is the engine that has consistently revolutionized science.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Ecuador a special place to visit?

The huge biodiversity we have. As biologists, this is fantastic as there is much left to do and explore in terms of biodiversity both in the micro and macro world. Ecuador is a beautiful place; beyond any of the problems and limitations we face. It’s a small country, but there are so many things to see – we have the Andes, the coast, the Amazonia, and the Galapagos islands – it’s a small country with a diversity that is not easily matched with several drastically different regions in a relatively small area. The variation of each region also brings variation in the language, culture, food, etc making it an extremely rich place to have new experiences.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)