An interview with Laura Daza

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 28 November 2023

MiniBio: Laura Daza just finished her PhD at CinfonIA, at Universidad de los Andes in Colombia. During her doctorate degree, she has worked in a variety of projects ranging from Computer Vision to image and data analysis. She studied Biomedical Engineering at Universidad de los Andes, where she first found her passion for Image Analysis. She proceeded to start a MSc degree in Artificial Intelligence, and during this time she was offered a PhD fellowship to pursue her doctoral studies in the same area. She is part of the team at CinfonIA, which joined efforts with Coursera to generate the first Masters degree in Artificial Intelligence taught fully in Spanish, as efforts to democratize access to knowledge and remove barriers long imposed to researchers world-wide.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

Since I was very young, I wanted to know how things worked. I would disassemble things and more often than not, I was unable to put them back together. My older brother was the same, so this is something we would do together. My brother went on to study Medicine, but I realized early on that Medicine wasn’t for me. It became a commitment for me, between Medicine and Engineering, and I ended up studying Biomedical Engineering. At some point, while taking a subject called Processing and Analysis of Medical Images, I realized this is where I belonged! That this is what I wanted to do for the rest of my career.

You have a career-long involvement in image analysis and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

I studied all my early career in the same school – I used to live in a small town in Colombia. For University, when I joined, there weren’t many Universities in the country that taught Biomedical Engineering- Universidad de los Andes, in Bogotá. My brothers also attended this University, and it was very unexpected for me that the career I chose was very broad. I remember complaining about the fact that we had 3 exams all on the same day, which had nothing to do with one another: Circuits, Biochemistry and Probability. So it was very intense. However, in general, the cool thing about this career is that it gives you a very broad vision. It gave me perspective of very different fields. In my case, the field that caught my eye was Image Analysis. I had a University insurance which my parents bought when I was little, that covered 6 semesters of my career, but my career was 9 semesters. But I knew I could take extra subjects during the first few semesters, so I did this, and finished my BSc in 7 semesters. During the remaining 3 semesters I took in subjects of a MSc degree, which were validated once I actually joined the MSc degree. I was while taking these subjects, which were very focused on research, that I met the person who later became my advisor. When I joined the MSc, he told me he had been awarded a grant to hire a PhD student. So I ended up not completing the MSc but instead joining the PhD directly – I just recently completed my PhD after 5 years of research! The COVID-19 pandemic made it longer. While our work is mostly done in computers, and this work per se wasn’t really affected, we are required to do an internship abroad to be able to graduate. And of course during the COVID-19 pandemic we couldn’t travel. Only last year I was able to go abroad, to Johns Hopkins, to do my internship. I’m currently applying to different positions abroad.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a PhD student in Universidad de los Andes?

When I started my PhD, the only other two PhD students in my advisor’s lab had just graduated. My advisor, Pablo Arbelaez, is relatively young, and he had built his career abroad in France and in Berkeley, USA. He came back to Colombia, to Universidad de los Andes, wishing to do research in Latin America. He arrived in Colombia one year before I joined his class, so understandably, his team was very small. He told me he wanted to establish a solid team. When I joined his team, my position was immediately semi-PhD, semi-postdoc. I was involved in 5 or 6 projects from the beginning, and involved also in training younger students, guiding them in their projects. He also heavily involved me in grant reviews, and reviewing applications of younger students. Soon after, he hired another PhD student, and together we helped Pablo with the group. Now the group has grown enough and Pablo went from being a group leader to being the director of CinfonIA. Most of the projects are related to Computer Vision, and data processing of data that are not necessarily images, such as electrocardiograms.

You and your group generated a MSc in Artificial Intelligence in Coursera – can you tell us a bit about your project?

This is a huge joined effort between Coursera and Universidad de los Andes – we’ve led this initiative between several groups, including Pablo’s. It’s no surprise to anyone that Artificial Intelligence is fashionable right now. But all the articles, books, etc, are in English. So you must learn English in order to make the most of the current knowledge in AI. We found it unfair that this is the case, because it’s a barrier to many people who don’t speak the language. One thing shouldn’t be a pre-requisite for the other. Imagine that you are not even considered for a MSc because your skills in English are not great. Access is restricted already on the basis of other things, and language shouldn’t be another imposition. So we created this MSc which is fully taught in Spanish. We established a whole program, now approved by the Ministry of Education in Colombia, and available to everyone in the region. This was a huge investment, with the idea of democratizing access and remove barriers.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Colombia, from your education years?

Honestly my older brother was always my inspiration. He is a genius who does well in everything, but he’s still very relaxed. He always encouraged me to learn, and go beyond in my own career. He’s the person who most supported and encouraged me during my PhD too.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Colombia?

I have had a chance, but I look forward to doing this further.

Are there any historical events in Colombia that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

I don’t think so. In Colombia, investment in science funding has never been great, and it’s always very competitive. This is a hindrance for science. There are many calls which aim to make research more inclusive and that promotes that science reaches regions without many resources or access to education and technology, but it’s all very limited. Investment in science and technology is very limited. And this is understandable to some extent. We are a developing country with lots of other issues we need to address in parallel to science. It’s a tough choice.

Who are your scientific role models (both Colombian and foreign)?

One of my role models is Pablo Arbelaez, he is a fantastic researcher. He has an incredible international career, and it’s great he decided to come back to Colombia. I admire him greatly as a researcher. Also, in my area it’s uncommon to see successful women, so there are two German researchers that I truly admire: they truly dominate their respective fields. They are Lena Maier-Hein who is a leader is robotic surgery, and Julia Schnabel whose expertise is segmentation and analysis of 3D images from biomedical disciplines. They are both always at the frontier of knowledge, and I find it inspiring that they are leading the way, in a field largely dominated by men. Both are a role model for me, since the beginning of my career. Their names are legendary and present in all the main papers of my field.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Colombia, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career both at home and abroad?

When I joined Pablo’s lab, he didn’t have other students, so there was already no competition. It was all a matter of great timing for me. From my BSc degree in Biomedical Engineering, our career was very well balanced in terms of gender – almost 50:50. In the lab, it’s waves: in some semesters it’s all women, and in some others, it’s all men. But the group historically has trained more women. Right now we are 4 women and 1 man. So for us this disbalance has never been major. Last year, when I was at Johns Hopkins for my internship, I joined a lab with 15 people – I was 1 of 3 women in total. I joined a project which involved several other investigators, and there were sometimes meetings with over 30 people, where I was the only woman. Honestly, this made me feel intimidated, especially because many of the senior leaders were 60 year old men, all super serious. I felt sometimes intimidated as a young, Latin American woman in this context. I feel that in my PhD lab back in Colombia I was living in a bubble. By chance, at Universidad de los Andes, Pablo ended up in a Department of Biomedical Engineering, instead of Computer Systems and Mathematics. I feel otherwise this would have affected the gender balance even more, to a 90:10 ratio perhaps. Another place where it becomes clear that there is a gender misbalance is in conferences relative to my area: in most conferences, the queue for the women’s toilet is very long. In my conferences, there is no queue at all. We make fun of this because you see huge queues for the male toilets but not the women’s.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Colombia?

As a foreign researcher, while looking for postdoctoral positions or other jobs, I have felt a prejudice, not necessarily because I’m a women, but because I’m Latin American. I feel a bit of skepticism regarding my capabilities. Especially in job interviews, I get many questions regarding my University -one feels they are implying that they are hesitant on whether my training is good enough. I have had friends studying abroad who have confirmed they feel the same way. I think the only thing left to do is to demonstrate that we’re actually really good.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

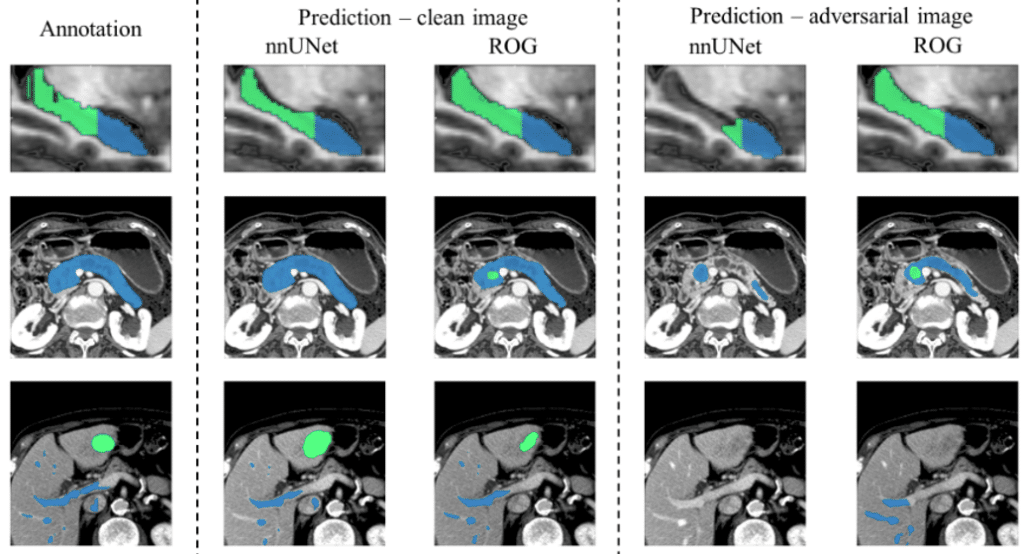

My focus is not fully in microscopy-based mages only. I work a lot with magnetic resonance, as well as with whole slide images of tissues: these images are full of details and they are absurdly big – logistically, for us, these images are super difficult. Just to load the image, it takes a while. To process the image, you have to get very creative to do adequate segmentation – there’s just so much information all at once. I’m always surprised about the heterogeneity of tissues – usually our samples come from the pathology department, so we usually know there’s something ‘wrong’, but it becomes a hunting game as what is abnormal or unexpected in the images.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy?

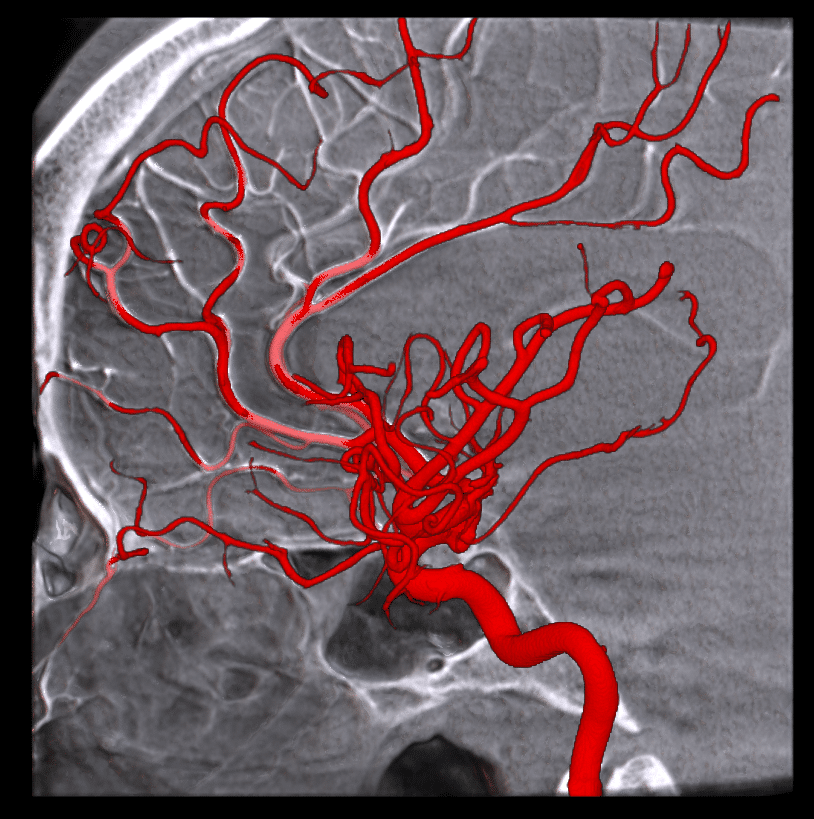

Right now we are working on a project in which we are studying vasculature – tubular structures. There are people who have the aorta divided in half. Me and my colleagues sometimes wonder this person is still alive, when the aorta is divided and the person doesn’t bleed out.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Colombian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

At the beginning, when you start your career, it’s very scary. Especially when you have a pressure knowing that the biggest research labs are in Europe or in the USA. This makes you feel that perhaps as a researcher in Colombia, you won’t go that high. But it’s possible. In fact, it’s a matter of not giving up, not allowing yourself to become intimidated by the system. One of our favourite phrases in CinfonIA, is that Latin America is full of talent, and all we have to do is foster it. I think the name that Pablo has made for himself, has allowed us to get certain types of funding, and the research we are doing in Colombia is not second class compared to the one they do in Europe or the USA. Don’t forget this. Another fear is the low pay – it’s a common question to wonder ‘how will you live, and for how long?’ given the unstable funding situation of science. But we loose sight that the salary, in relative terms, is equal in Europe or the USA – the salary there might be higher, but the expenses are very high too. Science is poorly paid everywhere, it’s not something specific to Colombia.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Colombia, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

There’s something I really love about the research I do: there is lots of investment in imaging: be this avatar generation, Instagram, etc. In Latin America, this research exists too, but this is mostly in the area of Biomedicine, Medicine and Conservation. I think this is due to the fact that we have those specific needs: there is a lot of medical needs, and the Amazon rainforest is in danger – so these needs guide the applications of a discipline as image analysis. I like this about Latin America: we are encouraged to pursue work that is useful to solve our everyday problems. I’d love to continue to be engaged in this area, to use this knowledge and skills in my country, to exert real change in my country. To make a difference.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Colombia a special place?

In terms of diversity, Colombia has everything. The people are super nice – it’s the type of country where if you look like you’re lost in the street, someone will come to you and ask you if everything is alright and if they can help you. You feel welcome and like you belong. It’s funny for me when I’ve been abroad in other countries (other in Latin America) where people hardly interact. In addition to the people, the country is truly beautiful: the mountains are amazing, like taken from a fairy tale – we have coasts in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans – at some point in the year one can see whales migrating. And if you’re really adventurous, you can go to the Amazon. We Cali, which is the capital of Salsa. In Medellin people are super nice, and so on. Every place has its own personality. There’s always something to do and something to see. The food is not hot though but we have empanadas, arepas, a huge variety of fruits, etc. I know also that now Disney has put Colombia in the map, with their movie Encanto: during the COVID-19 pandemic I lived in Barichara, which is the little town that served as inspiration for Encanto. It’s a beautiful place lost in the middle of the mountains. It’s at the edge of a canyon. You can go in the evening to see the sunset. The houses don’t have glass – it’s all still wood – it’s a fairy tale!

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)