An interview with Erick Hernandez Renjifo

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 5 December 2023

MiniBio: Dr. Erick Hernandez Renjifo leads the Materials Analysis team at the Institute of OMICAS research at Universidad Javeriana de Cali, Colombia. Erick started his career in Materials Sciences at Universidad del Valle. He has had a versatile career in both, academia, and industry, where he worked at a copper steelworks factory and a car assembly factory (FANALCA), where among his main tasks were assembling Honda motorcycles. He completed his M.S and PhD in Engineering at Universidad del Valle School of Materials. During his scientific career, he has worked mostly on films, coatings and metallurgy, as well as coatings processing, mechanical testing and materials characterization. Among the platforms he regularly uses for materials characterization are AFM, SEM, DRX, FTIR, TEM, among others. In recent years, he has been one of the researchers pushing for the formation of a network of microscopists in Colombia, which can promote, foster and facilitate exchange of expertise, dissemination of information and knowledge, and training of human resources.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

My scientific career is a bit curious. I never imaged I would be doing a PhD or pursuing a career like the one I have. My family is from humble origins, my mum was a single mum, I have another sister, and we were both good students. I did really well at school, I had first place in several subjects and so on. Before entering University, a teacher who taught me Chemistry at school suggested that I study Material Sciences – which was a relatively new career in Cali, Colombia. I did join this degree, after she told me it was a career with lots of potential. I honestly loved it, although I found the first years of engineering very similar to other engineering careers. Some people join a degree and then swap careers, but I loved mine from the start. I studied at Universidad del Valle.

You have a career-long involvement in image analysis and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

Once I finished my degree, I knew I had to start working right away and I joined industry, I did an internship in a multi-national copper steelworks factory. I stayed there for 3 years and went up in the professional ladder. In search of better opportunities, I found another job at FANALCA: Fábrica Nacional de Carrocerias (or Autopartes) (National Factory for Car Parts, in English). It’s one of the factories that assembles all the Honda motorcycles at a country level in Colombia. They have a lot of enterprises within FANALCA, so the benefits and salary were great, and I also wanted new challenges. I was there for almost 3 years too, and there, by serendipity, I re-met the person who later would become my wife. My wife is a full Professor in Materials Science- with a successful academic career. At the time, it was clear that in order to have prospects of career growth, I would need at least a Masters degree. So in 2015 I started a MSc in Mechanical Engineering at Universidad del Valle. I joined this university because it was the only one that allowed me to study and work – I was able to study in the night shift, and work during the day. The first semester was very hard. And Mechanical Engineering is very tough. I had to study 3 times as hard. My schedule would start at 4am and end at midnight or later in order to do both things simultaneously. Eventually though, I realized that I would have to choose and couldn’t continue with a double life like this. My wife convinced me to join the University – this was a difficult switch because in industry there is a lot of skepticism about academia, and in addition, some things, like writing a grant, or winning a scholarship or fellowship seems nearly impossible and like something that happens to only very few. So I didn’t think, at this point, that I could do something like this. My wife had spent all her career in academia, and she knew the ropes, and encouraged me to switch from industry to academia. So I quit my job, and without any earnings, just with my savings, I realized I could afford one year of studies. I sold my car and went back to live with my mum who luckily supported me. This allowed me to really dedicate enough time to my studies. This allowed me to get more involved in projects, write papers, and do research as full time. Once you’re inside the academic track, I realized it wasn’t so impossible. I submitted a project with my then supervisor, and this allowed me to earn a stipend to pay for my living expenses and for my fees at the university. I think this stipend was a salary similar to the one I was earning in industry. So the rhythm of my life became more bearable. I also found the life as an academic much more relaxed than the one I had led in industry where I had no time for myself at all. I learned a lot in industry, but I think this switch made me reflect on what I wanted from life.

Once I finished my Masters degree, I considered going back to industry, but right around the time when I started applying for jobs, a PI from Materials Science offered that I do my PhD in his lab. I really had to think about it, because I found the masters really tough. But balancing out things, I realized I could revalidate several subjects, and in the end it seemed that doing a PhD would make sense. It wasn’t a decision based on finances, but rather, on lifestyle. At that point I was living with my girlfriend (now my wife), and so we both belonged to the same world. When we got married, because she is an academic, one of the benefits was a fee waiver for partners – in this case, me and my fees. Within 6 months I found my own funding, and the university also offered me the chance to teach 2 engineering courses. This helped me in two ways: it gave me an income and it also gave me the opportunity to gain teaching experience. All 4 years of my PhD I taught several courses, so this was great. My PhD project was in thin films that are done mostly in metals but also other types of material. We use a lot of techniques for their characterization, and one can really obtain a lot of information from different technologies. From these characterizations we were able to publish a lot. By the time I finished my PhD I had 8 papers, which was a relatively high productivity. It also gave me the chance to gain experience in writing papers and in the publication process. I graduated from my PhD in 2022. Since my wife has a tenured position, my options in terms of career were to some extent limited in that I didn’t consider doing a postdoc abroad or something under these lines. Tenured track positions in public Universities in Colombia are very rare, so it didn’t make sense for her to relinquish her position. In Cali there are very few universities, and only one is public (Universidad del Valle), so the job market is very complex. I started looking for projects here in the region, so that I could work as a postdoc. By serendipity, a call came up at the OMICAS institute at Universidad Javeriana, and they were looking for a person who had a profile similar to mine – someone familiar with materials sciences who was able to use multiple techniques for the characterization of materials. But the education level required was an MSc – this job was under an open contract. I applied anyway, and I was called for interview, and they offered me the job to coordinate the Nanotechnology Lab. The Institute has lots of projects, and I had strong foundations on many techniques. For instance, I used SEM in about 60% of the papers I’ve written. During my PhD I was working with thin films, and SEM was one of the main tools for characterization – we didn’t have AFM at the time. I also did a lot of image analysis during my PhD. We also used a lot of TEM in collaboration with colleagues in Zaragoza, and we got a European grant to work on this project, including a lot of image analysis. So I felt very confident and very strong once I joined the OMICAS institute at Universidad Javeriana in Cali.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a Materials Analyst at Instituto de Investigación OMICAS at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana?

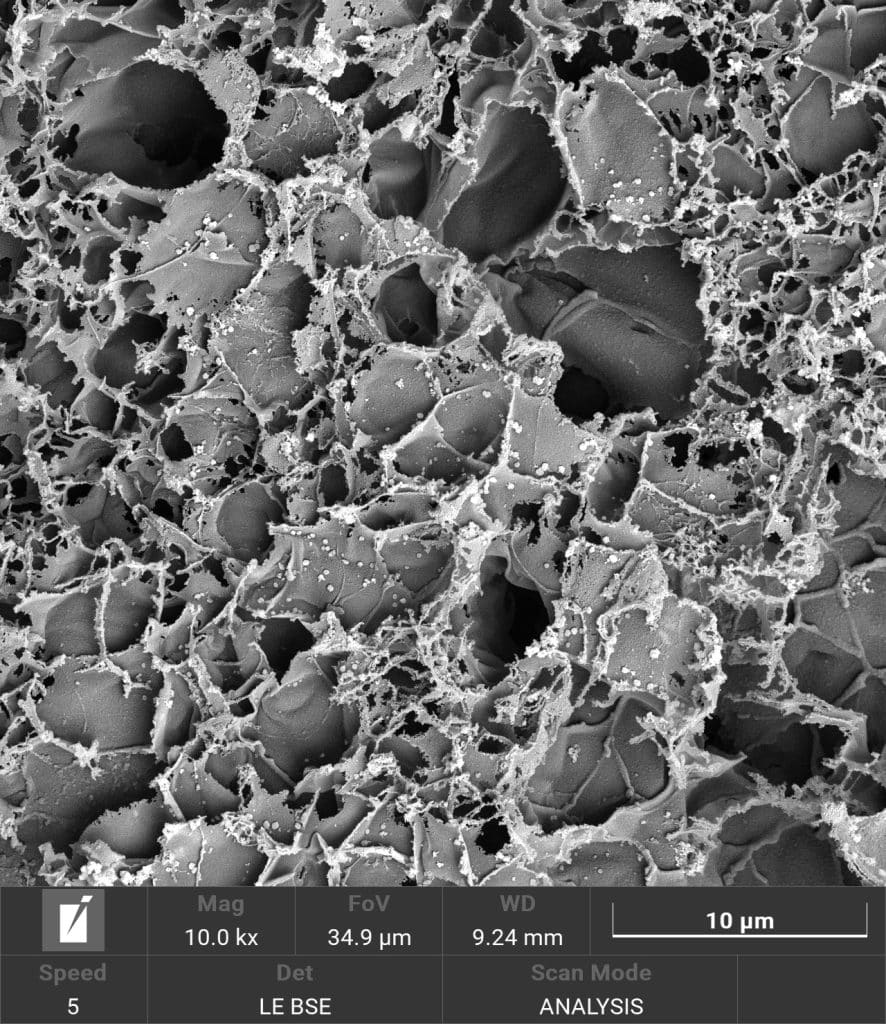

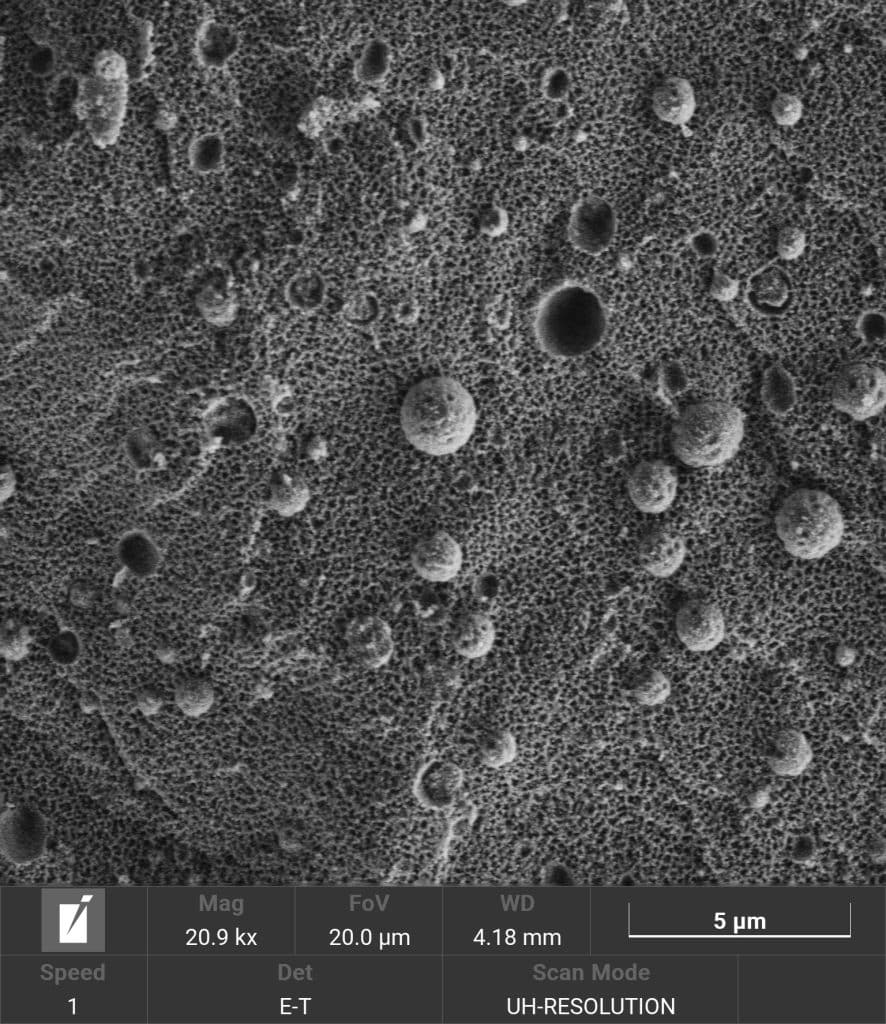

When I joined, there were a bunch of instruments that I became in charge of: an Oxford Instruments Cypher S AFM, and many other platforms for materials characterization. Last year I started doing SEM almost every day. The institute has many different research lines in the omics disciplines, but there is a very strong line that focuses on characterization and synthesis of nano-sensors for the detection of analytes. We work with nano-sensors of graphene oxide, synthesis by CO2 in polyimide, then we functionalize them. We also developed and patented here a potentiostat to perform measurements in the nanosensors we create. With them we perform different types of measurements: SARS-COV2, emerging water pollutants, greenhouse gases, soil remediation in agriculture settings, etc. So the synthesis of sensors is a main area we work on. And when we work on graphene, a main technique used for the characterization of this material is SEM. So I spend a lot of time at the SEM microscope. I started contacting different vendors and suppliers, for instance TESCAN for SEM, and Oxford research for AFM, and I requested training from their specialists. Representatives from different parts of the world, including the USA and the Czech Republic came to Colombia to provide training. One of the main trainings I got was to do cryo-SEM with liquid nitrogen – a more complex technique for organic chemistry and biological samples. I also traveled to Brno in Czech Republic and spent 3 days at the TESCAN factory – they showed me how they generate the microscopes, and their latest equipment. I received training in cryo-techniques, and this strengthened the possibilities of what I can do here. The institute is growing a lot, and I think my skills are highly valued here. Right now I do some research, but my role is much more of research support. But this might change soon, if I can dedicate more time to research. We support projects of many organizations like Bezos Earth Found, Gates Foundation, PTFI, World Bank, Minciencia, etc. this allows us to obtain funding for state-of-the-art equipment, and we have a very strong infrastructure.

On a different topic, I think here in Colombia, the groups working on microscopy are not very united – there is not a lot of dissemination of information and capacities, nor strategies for collaborative work. This has many different complications, including the fact that without a network of experts, when one has questions about how to process a sample or how to perform a certain technique, there’s no one to ask for help. There are some published methods and some information in the internet, but it’s never 100% what you need, or with the level of detail that you need. So I started inquiring about the operators of microscopes throughout all the universities in Colombia, and I generated a database with all the microscopists I could find and their expertise and contact details. I focused on the analysts and operators rather than the PIs because many PIs don’t know how the instruments are used, or not with a huge level of detail. I eventually formed a WhatsApp group so that we could more easily contact one another. This has helped us to form a network to disseminate information about courses, to share expertise, and so on. Now we are about 25 different people in this WhatsApp network. That’s where I first met Ivan Rey, one of the researchers you recently interviewed in this series too.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Colombia, from your education years?

I studied in a public university – I had many things, but not everything. But in the public university, I had colleagues and friends who had very little resources, in great poverty – some didn’t have food, some didn’t have enough money to make photocopies. I am where I am now because my opportunities in academia allowed me to grow, and they provided the funding I needed at the different steps. When I started working as a lecturer, I again noticed that poverty is a huge issue that becomes a barrier, and this is a pity, including for people with a lot of potential. I’ve tried my best to pay back the help and inspiration I received when I was a student, and so I try to help my students in whatever way I can when they face hardships that ultimately impact their studies and their career. From industry, a main thing I am grateful for is the network and relations I was able to build. This has allowed me to help some of my students to enter the different industry jobs, so they could start receiving an income.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Colombia?

Not so many. I’ve done most of my career in Colombia. But I do have many Colombian colleagues who are doing research abroad: the ‘diaspora’ as it’s known. Colombia had a huge brain drain in the last few decades. The country doesn’t yet have a strong industry, or even academia, that can place all the PhDs with a range of expertise. This forces all those experts to stay abroad or to go abroad. About 95% of PhDs are working in academia here in Colombia. There aren’t enough jobs in industry – their vision is still very limited in industry regarding the value of the PhDs – they prefer to hire technicians or engineers, rather than invest in people who can optimize processes or do creative work for research. In other places in the world, the majority of researchers with doctorate degrees are in industry.

Who are your scientific role models (both Colombian and foreign)?

My mentor, Dr. Julio Caicedo who is at Universidad del Valle, is an extremely bright person. I worked with him since I was doing my PhD, and his guidance has been vital in my career. There are many scientists whose work I admire, but with whom I’ve never worked. Another scientist I also see as a role model is Dr. Andres Jaramillo Botero -the director of the institute where I work. He’s a bright man, and I admire the efforts he does to direct the institute, to help different research lines, and to even lead another ‘life’ at CalTech. He’s also the director of the PhD program here at Universidad Javeriana in Cali. He’s very knowledgeable in a range of topics including biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, etc. And another person I admire a lot is my wife – at 30 years of age she had finished her PhD, and by 32 she was tenured. This is not very common! She’s an excellent and versatile researcher.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Colombia, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career both at home and abroad?

I think it has improved a lot compared to previous times. At the OMICAS institute, in my group I’m the only man. I feel it’s also somewhat very field-specific. Biology has a lot more women (60-70%). In administration, 100% are women. But I have seen other research groups where women are scarce. This is very old-school and a very prejudiced view. There is still a lot to be done. There are lots of engineering degrees at Universidad del Valle, but the vast majority of students are men. I think especially in public universities – reaching people with scarce resources, there is a very old-school mentality which is a barrier for women since much earlier. So it’s important to reach girls and young women early on to break this cycle, and really convince them that they can do whatever they want, and study whatever they want. When I was studying my masters in mechanical Engineering, there were no women at all – I think this is linked to a concept that Mechanical Engineering means fixing a car and being covered in oil, and that this is not a job suitable for women. These days that’s not what a Mechanical Engineer is – we are designers and mathematical modelers. Regardless, both types of job can be done by women. So it’s a matter of breaking these prejudices and society-imposed barriers.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

SEM is my favourite – it’s an incredibly versatile technique and you can apply it to a lot of things. In the field of material sciences, it has a ton of applications, for example, in the textile industry, for fashion design, SEM has a place. It’s also more affordable than TEM – there aren’t enough experts, enough instruments, and therefore it becomes difficult to perform. AFM is also a great tool – you can reach much higher resolution than EM, but it’s not as fancy as EM. It does give a lot more information though… SEM produces beautiful images on the other hand. But both EM and AFM platforms are still both very costly in Colombia.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy?

I’ve seen lots of insects – the insect world (and the micro- and nano-world) is fascinating. The first time I saw a fly’s eyes or a mosquitoes’ eyes, I was terrified about their impressive anatomy and physiognomy. Also surprising are nanoparticles or nanotubes. I’ve worked on optimizing methods to see 10nm nanoparticles using SEM, which has not been an easy task. But honestly every day I see something new and fascinating: vegetables, animals, etc. Regardless of how many samples one has seen, there’s always some novel and unexpected sample.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Colombian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

You have to be perseverant and resilient, high level science requires a lot of dedication. There are funded opportunities to specialize in certain areas of knowledge but they are scarce, for this reason you have to be very persistent and consistent in the search for these. As far as I know, in Colombia there is no certified training in the handling and analysis of samples by electron or optical microscopy. The expertise is acquired at the postgraduate level by interacting with microscopists at universities and during the development of research. It is a very beautiful and versatile science, transversal to almost all fields of science and allows us to demonstrate phenomena visually, which is a very fast technique to elucidate many phenomena. In other developed countries, there are specialized programs in microscopy, which is ideal. Colombia is still far from training people in this area because the technique is not accessible to all professionals, and it is still expensive. This does not condition the ability to be resourceful when it comes to training in any area of science: the key is to be resilient and persevere.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Colombia, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

In the WhatsApp group I mentioned before, we have discussed a lot the need of strengthening the network of microscopists in Colombia. Unfortunately, all projects need a leader. If there’s no one who generates momentum, it’s difficult for projects to take off. At the moment I haven’t taken the lead of this because my time is truly very limited. But I think we should do this to strengthen capacity-building in Colombia. We need a critical mass, and momentum. Still, in the group we have, there are many experts from Universidad Javeriana de Cali, Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá, Universidad de Antioquia, Universidad del Valle, and other big universities in the country. But I feel this is a snowball that will grow. It must, because we need better equipment, more highly skilled human resources, more funding, etc.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Colombia a special place?

Its people. Beyond any social, political, economic problems we face, or the violence that some places in Colombia face, the people are the main factor that makes Colombia special. These difficulties drive many people away. But in general Colombians are very perseverant, very warm-hearted, very kind and welcoming, and this makes it easier to face the different problems that the country faces. Otherwise the difficulties would be unbearable. The second best thing is the natural territory – we have spectacular things in our country that are unique and you can’t find anywhere else: the rainforest, the mountains, the seas, etc. It’s a beautiful country, and open to everyone.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)