An interview with Maribel Torres Velázquez

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 6 August 2024

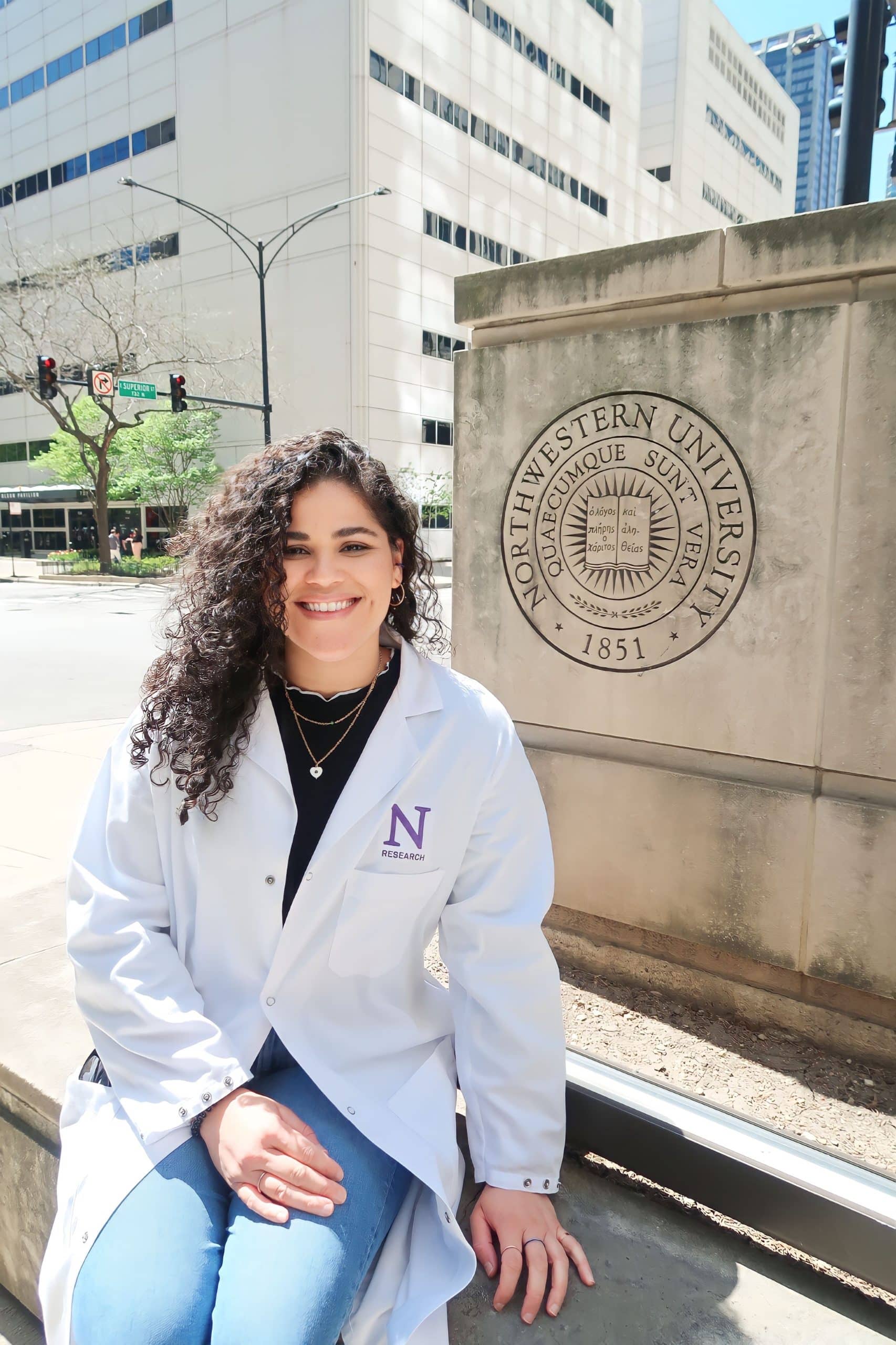

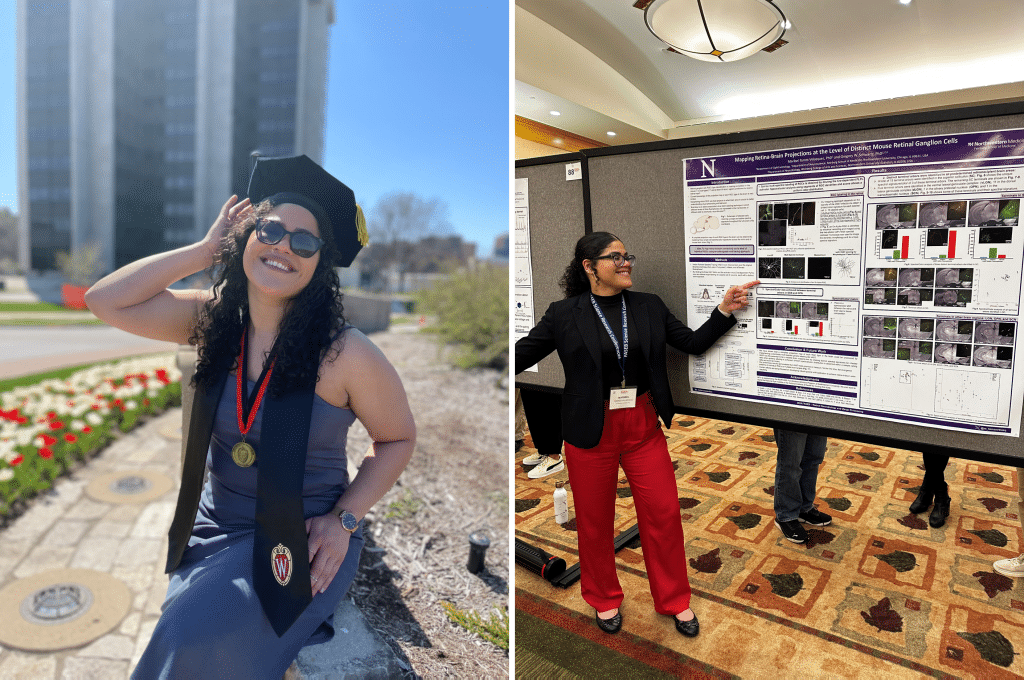

MiniBio: Maribel Torres Velázquez is a NURTURE postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Prof. Gregory Schwartz at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University, where she uses microscopy to study the retina-to-brain circuitry. Specifically, she aims to uncover the retina-brain connectivity map by identifying to which unique brain areas different retinal ganglion cell sub-types project to. Maribel was born in Puerto Rico, where she completed her bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez (UPRM). During her early career, she had the opportunity to do several internships with the National Weather Service, NASA, and General Electric. Although her initial career interest was to design weather radars, she later developed a passion for image and signal processing that led her to pursue a career in Biomedical Engineering. Therefore, for her postgraduate degrees (MSc and PhD) she joined the University of Wisconin-Madison (UW-Madison), where she further pursued her interests in medical imaging processing. She has been a member of multiple organizations including the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS), the Graduate Engineering Research Scholars (GERS) at UW-Madison, the Alliance for Increasing the Participation of Females in Engineering (AiPFE) and the Advancing Females to Professoriate in Computing (FemProf) at UPRM, the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers (SHPE-UPRM), and others, whose aim is to promote equity and inclusion of under-represented groups in science. Maribel recognizes the role of mentors, outreach, and education in ensuring better representation of Latin Americans and women in STEM fields and is heavily involved in these activities to ensure the next generation of scientists enjoys improved access to opportunities.

What inspired you to become a scientist/engineer?

I became an engineer – a big inspiration for me was my mom. She is a physical therapist, and since I was very young, I spent a lot of time at the hospital due to some asthma complications. Therefore, I think I knew very early on that I did not want to become a medical doctor because of my experience of being sick. Once I entered high school and began exploring different career options, my Mathematics teacher told me about the Pre-engineering Summer Camp at the University of Puerto Rico in Mayagüez. One had to apply, write some essays, take some exams, and if you were accepted, you got to spend 2 weeks at the University, exploring what the different engineering fields were about. That was my first experience in the field of STEM. I come from a middle-class family, I went to public school, and although I knew what the University was in general, I had little insight into its details. For example, I wasn’t sure at all about what the different engineering fields entailed. So, this experience proved to be useful and I chose to study Electrical Engineering. Originally, I planned to learn about weather systems – I wanted to design electromagnetic radars for weather forecasting, and climatology research – all about meteorology. Later in my career though, I had the chance to work on image processing, and I fell in love with this field. Eventually, I would go on to specialize in Biomedical Engineering. I found my way back to Medicine! I found a happy middle ground between my passion for engineering and medicine, without having to be a medical doctor. Funnily, when I did my PhD, my doctoral thesis focused on brain imaging including images from MRI, PET, etc. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I could not complete one of my research projects. This forced me to change directions for this project, and instead, I took on a project that focused on investigating hamstring injuries – very related to my mom’s field in physical therapy. She was super excited that I had “changed fields”.

You have a career-long involvement in engineering and now, microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

My career path is full of twists and turns. When I started college, I had a clear plan in my head about how I wanted my career to be. I followed this plan to some extent: when I started pursuing my Electrical Engineering degree, I also studied advanced physics and meteorology to understand hurricanes, how they are formed, etc. That’s how my path began – I did several internships at the National Weather Service and NASA. After these two internships I realized that although I was extremely passionate about meteorology, I could not see myself doing this for the rest of my life. I was interested in weather radars, sensors, and everything related to meteorology, but it was not something I would want to do day in and day out. I realized that a thing that I found appealing about meteorology was the possibility of helping people. After all, hurricanes and other natural disasters usually come hand-in-hand with humanitarian crises. I wanted to do something that would help people. And although meteorology helps of course, I didn’t find it fulfilling. So, I knew engineering was the field I loved, but I had to narrow down my choices. I did several internships in academia and industry – including two at General Electric, and I loved it. At this point, I decided that I needed a master’s degree. I didn’t know that there were various academic funding opportunities. But how it came to happen was that during the 3rd year of my undergraduate degree, Prof. Nestor Rodríguez who was a professor in computer engineering (and has since retired), was teaching that day and was asking around ‘Who is Maribel?’, I said it was me, thinking that I had done something wrong. Instead, he proceeded to tell me that one of his goals as an engineer was to promote the better inclusion of women and to encourage them to pursue a PhD with the hope they would one day form the next generation of PIs. At the time, this initiative was called Advancing Females to Professoriate in Computing (FemProf). Every year he selected female students in electrical and computer engineering and computer science, with a high GPA and great potential to pursue a career in academia to become part of FemProf. He then mentored them to be able to enter graduate school (including the process of getting fellowships). So, after this conversation, I met with him, and he told me about the Opportunities in Engineering Conference at the University of Wisconsin-Maddison (UW-Madison) and helped me with the application process and recommendation letters to be able to attend. This conference was aimed at underrepresented groups in science. During this conference, similar to the engineering camp I did as a high school student, the hosts told us about the different graduate engineering programs. The Department Chairs told us about their research, and it was there that I met Dr. Beth Meyerand who became a lifelong mentor. She was at the time the Chair of Biomedical Engineering. She spoke about her research, and how she was using image processing methods to understand and study the brain and to develop computational algorithms to detect diseases or improve prognosis and treatments. This was a big surprise for me because, at this point, I didn’t know that engineers could be in this intersection of Medicine and Engineering. As a coincidence, my uncle was diagnosed with syringomyelia, which is a neurological disorder that, if not detected early on, can result in a decrease in motor functions. With my uncle, doctors failed to detect it early on, but eventually, after several studies including imaging, he was given his diagnosis. All these life events made me realize I could use my abilities in Engineering for this field. So, after meeting Dr. Meyerand, I asked her if I could spend a summer in her lab. She agreed and I did a summer project. I eventually applied to graduate school and completed my master’s degree with her. For the PhD I switched labs (but remained at UW-Madison), with a PI who had been her student too. After completing my PhD, I joined Northwestern University as a postdoc, and I am now in the lab of Dr. Greg Schwartz. What led me to his lab was that many senior scientists had told me that it is important to expand our horizons, and develop abilities that we didn’t have to become well-rounded scientists. Something I wanted to do but had never done within the field of image processing was microscopy. So, I was interested in living in Chicago, and while searching on the internet to learn more about the research being done at Northwestern, I came across Greg’s lab’s website. The main research focuses on using microscopy to answer specific biological questions. And now I am here! I have been here for 2 years.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Puerto Rico, from your education years?

First of all, I consider myself extremely fortunate to have been able to study at the University of Puerto Rico- Mayagüez. Being such a small country, we have a very high-quality education. Although we might not have as many resources as in the USA or other countries, the education is great. The professors are excellent. When I defended my PhD, I highlighted and recognized the importance of many professors in Puerto Rico who gave me the chance to gain exposure to a huge range of opportunities. I had mentioned Dr. Nestor Rodriguez, but there is also Dr. Nayda Santiago. Together, they allowed me and other female students to attend several academic conferences to present our research, gain exposure, and get to know other scientists. Altogether I think the professor’s quality is what I’m most grateful for – with few resources, they have achieved a lot and continue to do so. They are very passionate people who want to positively impact the students and support the university for the good of the greater community. Without my professors (my mentors!) from my undergraduate institution, I wouldn’t be here today.

What do you do on a day-to-day basis as a postdoctoral fellow?

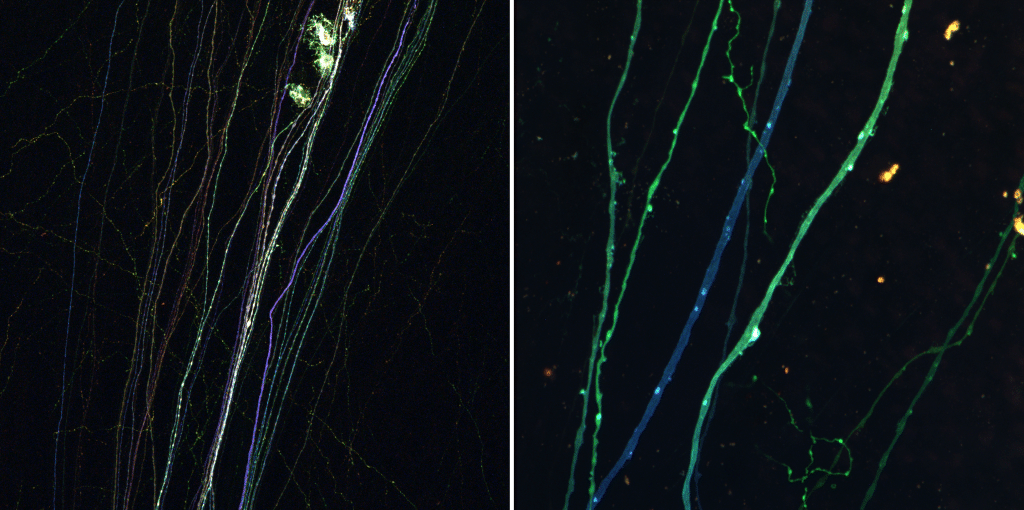

It’s super fun and super interesting. During my PhD, I never had the chance to do ‘wet lab’ work. It was solely computational. I did not work with animal models or anything similar. This all changed during my postdoc! My day-to-day now is super versatile. For my research project, I’m studying retinal ganglion cells. These are the cells in the retina that send information to the brain. My project aims to map where specific subtypes of the retinal ganglion cells go in the brain. We know about the different areas these cells connect to. However, we don’t know how specific those connections are regarding which cell subtypes connect to each region, and whether the same cell connects to multiple areas. To do this we use microscopy – spinning disc confocal microscopy and AAV. Besides working on my research, something I love about my current lab, and day-to-day work, is how it brings together people with a hugely varied set of skills. Some people focus on studying the retina, others study the retina and its interactions with the brain, and others do behavioral studies using visual stimuli. Being exposed to these differences in scientific backgrounds and skills is very interesting and has allowed me to learn and teach new things. I also have had the chance to mentor undergraduate and graduate students –something I enjoy. I love teaching and participating in outreach activities to bring knowledge to as many people as possible and learn from them too.

You came from an Engineering background and are now a Biologist. Was the switch between disciplines difficult?

My first year was very challenging. When I first joined the lab as a postdoc, I had never used a pipette (other than maybe a few times in high school and undergrad courses). I couldn’t remember how to use it. So, I had to acquire a huge range of skills very quickly. It was satisfying to realize I could learn and do many things on my own and at a very fast pace. Something I often tell my mentees is that a PhD teaches you how to learn. You learn how to find solutions. As an engineer (right after I finished my undergrad) I felt I already had some of these skills, but the PhD gave me the tools to do it quickly and efficiently, to teach myself whatever I needed to learn. But still, when I first joined the lab, people used terms I had never heard before, like ‘Use the 647’ and I would stare in confusion until it kicked in that they were talking about the ‘far red channel’. I no longer feel embarrassed to ask my team for help when I don’t understand something, which is also an important skill. Altogether I would say changing disciplines is fun, albeit challenging. It helped me realize that science is highly collaborative. It’s nice to have a specialty, but it’s probably even greater to have a well-rounded education and integrated knowledge that allow you to approach questions thinking outside the box. One thing I liked about getting my PhD from UW-Madison, which helped me during my postdoc, is that my pre-qualification exams (which were 5 and were oral exams), were all in very different areas, requiring one to have a great breadth of knowledge. Of the exams I took, one was related to Biology, two were specific to my research area – signal processing and clinical imaging, and the other two were outside my area: medical instrumentation and tissue engineering. Because of this, by the time I joined Greg’s lab, I could understand several aspects of the project. I had an idea of how the general concept works, if not the super-specific details – for instance of how a neuron works. This was challenging, but there’s something nice and encouraging about learning new things. It helps diminish the imposter syndrome 😊 I feel I don’t know enough sometimes.

You mentioned earlier that you are very keen on mentorship teaching and outreach. What is your philosophy about all these aspects (mentoring, teaching, and outreach)?

These aspects are all very important to me and without them, I wouldn’t be here today. All my contact with science and engineering had to do with all these aspects. I believe the reason why not many people like me are represented in these fields is that they do not have the same access to mentors or academic/outreach activities as everyone else, thus they don’t know about the opportunities out there. The reason why I engage in outreach activities is to extend these opportunities to others. If this is something that they want to do, then I wish to help them go on a path that will get them to where they want to go. I have found that opportunities come in chains: one opportunity reaches you, and then another and another. But I don’t think everyone has that first life-changing opportunity. Now as a postdoc, I feel I have more credibility to help. During my undergrad and PhD, I was involved in SACNAS (Society for the Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science). As a postdoc, I have significantly increased my engagement. I have reviewed abstracts for their national annual meeting and acted as a judge for posters and oral competitions. I am also involved in their mentoring program, and often when I meet students at this meeting, I give them my contact details so we can establish this mentoring relationship. I let them know about internship opportunities, how to get access to grants, how to contact PIs, how to apply for doctoral programs, and so on. I think these small tips can change the course of someone’s life. I hope what I do is helpful for them.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Puerto Rico? Now that you are in the USA, do you have a chance to still connect with the Latin American community, and how do you feel we should foster this collaboration when living abroad?

I completed my undergraduate degree in Puerto Rico. Of course, over there, I was not in a minority – I did not feel like I was, nor did I feel different. Once I started my PhD in the USA, in Wisconsin, this changed, and it was obvious. However, I was lucky to be part of GRES (Graduate Research Engineering Scholars) at UW-Madison, a fellowship program founded many years before, to promote the doctoral studies of students from underrepresented groups. This includes a two-year fellowship and the PI who accepts you in their lab pays for the remaining time (minus two years). Beyond the funding, it involves a real community – we do professional and outreach activities and social events together. So, during my time in Wisconsin, I always had a strong community of about 30-40 people from different engineering and science degrees. In this sense, I always felt very supported. Outside this community, there was little representation. However, the good thing is that this network was very supportive and included many success stories – this showed us that it was possible to aim high and achieve what we wanted. Through this program, I attended several ‘future faculty’ workshops/conferences and noticed how underrepresented we (Latin Americans) are in STEM. I attended several meetings and always met the same Latin Americans. In terms of what we should do in the future, I believe we need to continue building community and try to eliminate this sense of competition. We are not in competition with each other – in my experience, there is space for all of us to shine. As underrepresented minorities in STEM, we should support one another and create an open community. Something that has come out thanks to social networks, conferences, and workshops, is that many groups such as LatinX in BME or various other disciplines, have been created. This is what we need: the sense of community, and the establishment of role models. Once the younger students see that you succeeded in your career, they will be encouraged to pursue their dreams, without this inherent doubt of whether it’s even possible.

Who are your scientific role models (both Puerto Rican and foreign)?

My mentors, Drs. Nayda Santiago, Nestor Rodríguez, Beth Meyerand, Christine Sorkness, and Alan McMillan. It’s interesting – I think I would take their best qualities and make the perfect mentor. Nobody is perfect, but I think what I admired most from my undergraduate professors was their dedication and ability to do so much with few resources. They do things out of love for science, education, and their students. They are happy if they receive awards or other recognitions, but it’s not their primary goal. I think from them comes my passion for mentoring. About my graduate professors, Dr. Meyerand has a great passion for mentoring- like many women in science. From her I learned to dream big, to aim high, and that if the resources are not there, one can be resourceful to acquire them, to make things happen. I also believe that good science involves collaboration, regardless of how people look or anything else. So, if I put them all together, I think I would get the perfect scientific role model and mentor!

What is your opinion on gender balance in Puerto Rico, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue? How has this impacted your career?

Depending on one’s field, these differences are more or less obvious. In the Electrical Engineering department, we had 5 women professors, and the rest were men. Similar proportions when it came to students. It was shocking to realize that while many more women started in the same degree as me, by the time we graduated, it was me and 15 male colleagues. There I realized that it’s not that women are not interested – there is no retention. Women don’t feel welcome and end up leaving. I have felt this too – there is a strong prejudice that women are destined for soft skills and that we should be whatever it is that many men think we should be when in reality we should be free to choose whatever profession we want. I think the problem of retention comes from self-doubt and an unwelcoming environment. There are always microaggressions: the typical situation is that you’re in a room full of men, you give your opinion, and nobody listens, but then a male colleague says the same and is recognized for having a brilliant idea. But I have surrounded myself with strong and brave women who have achieved a lot and have made me realize everything is possible.

Unfortunately, I have found myself in situations where I had to defend myself and the fact that I was a recipient of a diversity fellowship to study at UW-Madison. During my career, some people would tell me ‘It’s not fair that you, just for being a member of an underrepresented minority group, have a fellowship, because we (members of the majority group) also study and work hard’. I would then find myself explaining that usually we, underrepresented minorities, have to work harder to be even considered for any opportunity: our GPA has to be higher to be considered at universities and our extracurricular involvement needs to be very strong. Knowing these additional challenges that you don’t face unless you belong to a racial or gender minority, is crucial. Many people from minority groups say ‘It’s not my job to educate people on why it’s important to eliminate these biases’. But sometimes life puts you in situations where you should stand up for yourself and it’s an opportunity to educate people on these aspects. But also, sometimes you don’t get the chance to do so: for instance, I have encountered biases by reviewers of scientific manuscripts – they see my two last names and that I most likely am Latin American and immediately believe my science is not strong or good enough. Anyway – there are many challenges, so when someone comes and tells me ‘Maybe you don’t deserve to be here, and the reason you are, is just because you’re Latin American’ it’s a completely wrong assumption. Correcting this notion is something I want to do, but it takes time, bravery, community, and resources to do it.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Puerto Rico?

Aside from the challenges I have mentioned before, I always suggest choosing wisely not only the type of research/job you would like to do but also the institution and the geographical location. When you move away from your country, you are leaving behind your community, network of support, lifestyle, and a big part of what makes you, you. Finding a new community is a challenge – to belong. Sometimes we don’t speak about it because we focus solely on science, but we are human beings, and for our science to shine, we must feel happy. I feel very blessed that I found a nice community in Chicago, but this was a big challenge. The second challenge has been to find my voice – we are still underrepresented. Thus, it’s important to find one’s place and that your voice is respected – that others listen to you and validate what you are saying. The language was a challenge when I first moved to the USA, but I now consider myself fully bilingual. I still sometimes ask a native speaker to read over things I write to fight that imposter syndrome that tends to return occasionally. Those would be my three highlights.

Are there any historical events in Puerto Rico that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

In the last couple of years, I think two aspects have impacted the research landscape in Puerto Rico. One is political: Puerto Rico is not free- it’s an unincorporated US territory. People don’t like to call it a colony, but that’s more or less how it functions. Many people outside the island, think that because we have the American passport, things are “easy” for us. But for us Puerto Ricans born on the island, who grew up there and didn’t come to the USA until much later, we see that this passport comes at a high price – the economic and general development of the country. Over the last few years, another huge thing is the natural disasters: we have been affected by hurricanes, earthquakes, etc. This of course often results in humanitarian crises with other complications such as the spread of infectious diseases: dengue, leptospirosis, etc. Climate change will continue to have an impact of course. But everything is linked: as an “unincorporated US territory”, recovering from these disasters is very difficult. As a result of these difficulties and the major debt that Puerto Rico has, many people have migrated out of the country. Many campuses and schools have closed. This diminishes the funding that is available to universities, and this has resulted in a three-fold increase in fees for students. Studying in the USA is incredibly costly, whereas in Puerto Rico it has always been a goal to have equal and affordable access to education. So, an increase in fees is a huge hit to this concept of accessibility. The number of students at university levels has decreased by a lot as a result.

What is your favorite type of microscopy and why?

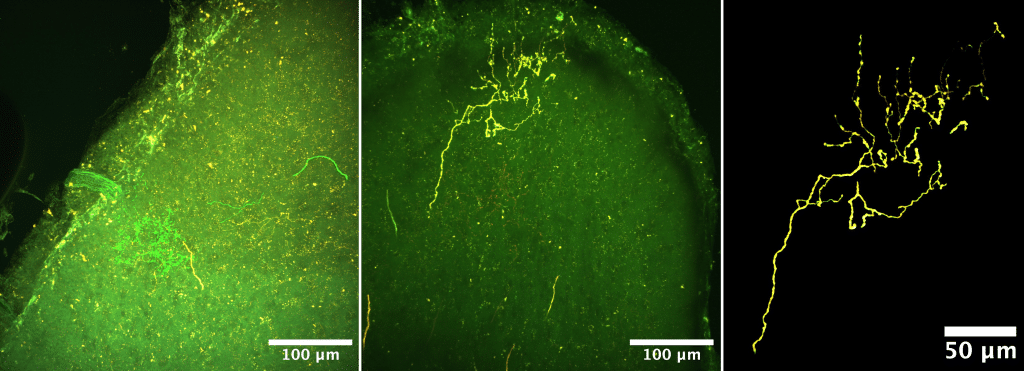

Fluorescence microscopy. I will always remember the first time I took an image of an axon in the brain and the retina – I was so impressed. I think confocal microscopy, as an example, gives you such great resolution to see so much detail. The fact that you can label different markers of different biological processes is mind-blowing.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

A huge part of my research is to see where retinal ganglion cells go in the brain. I see a few cells at a time (because of sparse labeling), so something impressive to me was when I imaged the superior colliculus – the area of the brain that received 90% of these cells and saw terminal arbors of two different cells (one red and one yellow) and they were so different, morphologically. It made me think about just how perfect nature is. And this one image made me come up with so many additional research questions! It was exciting. It made me think that if I continue working on this research area, I will have so many exciting research questions to work on.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Puerto Rican scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

I recommend they get involved with extracurricular activities and expose themselves to a wide range of scientific knowledge. Please don’t remain isolated in your lab and your university. Become an active member of academic and professional organizations. Find internships, because they will show you what you like, and what you don’t like, and they will give you the chance to learn new things and meet new mentors. I also offered this advice to my brother when he decided to pursue a career in engineering. Finally, do not fear learning new things. I love it, and sometimes it can be challenging but worth it since it has allowed me to switch disciplines and have such an exciting career right now.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Puerto Rico, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I see the field of science and microscopy growing and improving over time. Currently, the engineering departments at the University of Puerto Rico have many collaborations in biology and medicine (including microscopy), which exposes the students to new opportunities, allows them to get more funding for research, etc. The university is working hard to keep the resources it has and find new ones and people are very interested in pushing the field of microscopy. I think it’s exciting and what I think will happen is that more industries will be interested in establishing offices in Puerto Rico which could have a positive impact on the retention of professionals in the island and its economy. Additionally, I’ve always said I want to return to work and live in Puerto Rico, and if that doesn’t happen immediately, I still want to give back to my country. Therefore, I already engage in occasional academic and outreach activities there, but, if possible, I’d love to one day be an associated lecturer at the University of Puerto Rico.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Puerto Rico a special place to visit?

The people! Our culture is so beautiful and we have such a strong sense of community. We are all from the same country and yet can look so different – since we are a mix of races, Spanish, African, and Native Taíno. The island is beautiful too: we have mountains, sea, ocean, rivers – a lot of natural beauty. But I think the most special thing is the people’s resilience: we fight for what we believe is right and never give up. Anyone visiting Puerto Rico should get to know our culture, people, history, and gastronomy.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)