An interview with Andrés Di Paolo

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 27 July 2022

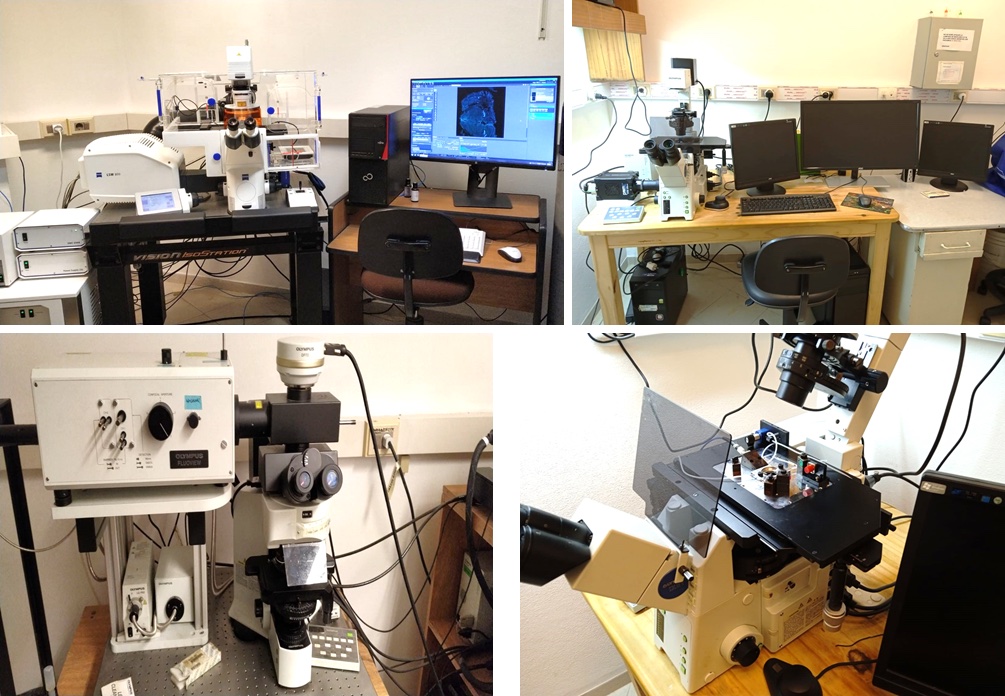

MiniBio: Andrés Di Paolo holds a hybrid position as a postdoctoral researcher and as a member of a microscopy core facility, involving several institutions including Institut Pasteur Montevideo, Hospital de Clínicas from UdelaR and Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas Clemente Estable (IIBCE). He is currently involved in the development of the first super-resolution microscope (based on STORM) in Uruguay. He studied his early career, masters and PhD at the Faculty of Sciences, in the lab of Dr. Jose Sotelo Silveira in Montevideo, and performed part of his PhD in the lab of Dr. Federico Dajas Bailador from the University of Nottingham, UK and in the Department of Proteomics of Dr. Thomas Kislinger in the Princess Margaret Cancer Research Center from Toronto, Canada. His duties involve a high level of versatility and multi-tasking which he find essential to thrive. He is married with Florencia Pages Videla 5 years ago and have two children: Ignacio “Nacho” of 9 years old and Piero of almost 2 years old.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

Since I was a child I was very curious and very observant. I have two children and I see the same behavior in the younger one (2 years old) nowadays. And then during my early education, this interest continued. I never liked the social sciences, and to this day I really prefer the natural sciences. I see science as less ‘polluted’ by human subjectivity. We develop tools to study natural sciences, but it’s something that to me is more “real”. It’s a personal philosophy: for me science goes beyond my daily job – I am a scientist in many aspects of my life (for better and for worse ). And during high school, Biology was something that attracted me a lot. When I entered University, I was sure this is what I would like to study. However, when I was in high school, the traditional careers were Medicine, Law, and so on. The scientific careers weren’t too well known or well-advertised, so when I was in high school I wasn’t even aware that scientific careers existed. Only when I was about to enter University and did my ‘homework’ researching the possibilities, I came across the scientific careers. Chemistry and Physics were less appealing to me, and I see this somehow as a weak spot in my career, but only now I am trying to catch up. However, Biology was always my passion.

You have a career-long involvement in cell biology, genomics and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about this path and what inspired you to choose these paths?

In Uruguay, once you enter University and the degree of sciences, you have some years with core subjects and later you can specialize. I didn’t really like macro-biology in general. I liked the microscopic world. I then did most of my career with Dr. Jose Sotelo Silveira. He came back to Uruguay after finishing his postdoc in the USA when I was in the second year of my undergraduate degree, and in parallel he was a professor of Cell Biology. I did my undergraduate project, my MSc and my PhD all in the same lab at IIBCE. When Dr. Sotelo Silveira started his own lab he started recruiting a first wave of students, of which I was part of. Once I joined, I stayed forever Since his work was all in Cell Biology, this is what I specialized in. He worked on axonal biology, and this is what I worked on in my PhD. I reckon there’s a component of ‘luck’ in this sense. If he had been doing something else, perhaps I would have worked on something completely different. In terms of microscopy, I was always very keen to do this. Clearly as a Cell Biologist, this is an essential tool. How I started getting involved as a microscopist is more targeted: I was working at IIBCE during my early career, and then the microscopy technical specialist, Marcela Diaz (see interview) had just moved to a different location, so the position became available. I had a lot of experience using microscopes and I decided to apply. I was selected for this position and then I had a chance to go deeper into microscopy in parallel to my MSc and PhD. There was a duality: I was both a researcher and a technician. But my heart is really that of a researcher: I like asking and answering biological questions using microscopy, and I feel this gave me an interesting profile. When someone come to the facility and asks for help in microscopy I can also give input as a biologist. I feel I re-framed what was possible in this respect, from the technical aspect of someone working at a platform/core facility. Dr. Leonel Malacrida is making huge changes as well in this respect in Uruguay. There is a system (perhaps obsolete) whereby members of core facility are expected to remain as technicians forever, without the chance of career progression. This needs to change, and Leonel and the Unit he has formed, has opened the eyes of many scientists, and I think this has had an impact beyond Instiut Pasteur Montevideo – but other places. He is also opening the eyes of people to show that Microscopy research is both valuable and possible. Especially in our region, buying commercial equipment is almost unrealistic: it’s too expensive, so having people who can build their own equipment and design new tools in microscopy to address scientific questions would be invaluable.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Uruguay, from your education years?

In Uruguay, primary and secondary school has perhaps declined in quality (this is not me saying this, but general statistics). However, at tertiary level, at least in sciences the level is great. I know many Uruguayan scientists who are very good, very solid and successful. I think the scientific career is great and it gives a lot of options for specializations. I feel secondary education is obsolete: it stayed on a model that perhaps worked many years ago, but is now outdated. In my opinion it doesn’t prepare you very well for University. There are many people joining University with certain expectations, and quickly realize they are poorly prepared and many times fail because of this. This is a pity. In many degrees the University doesn’t go back to teach the basics, and so for instance in careers like engineering, it’s survival of the ‘fittest’ – many people drop out relative to the numbers that join.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Uruguay?

I have been able to attend many congresses and conferences. I’ve been to Argentina and Brazil. I did part of my PhD in Nottingham, UK. The group leader was Federico Dajas Bailador, and he is Uruguayan. Later on, mostly in Uruguay, I now work with Leonel Malacrida. We are also in contact since a few months with Dr. Adán Guerrero, from Mexico, who works on super-resolution microscopy. I collaborate a lot with him these days because I am trying to establish a specific method of SR in Uruguay. Also, there are more and more, networks that are improving the links between Latin Americans.

Can you tell us what you do on your day-to-day work (both research and core facility)?

I have a lot of activities. Finishing the PhD brought about some level of relief for me. But my day to day is like juggling and multi-tasking. I do my job at the core facility, where my function is mostly of support. I do some teaching too to introduce users to the microscopes. And then I am doing the work whereby I am trying to build a new microscope to do STORM in addition of taking care of the general maintenance of the microscopes. Regarding the STORM setup, myself and a colleague, Joaquin Garat, are heavily involved in this: we read papers, we look for computational tools to get better images and do image quantitation. And then I have a project with Leonel, whereby we want to do intravital microscopy. We have the optical components, but it’s a completely new challenge, which is allowing me to learn a lot of new things. What I like a lot about my job is that it’s versatile. No two days are the same, so this level of multi-tasking keeps me greatly motivated.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Uruguayan researcher, working abroad?

My greatest barrier when I went abroad was the language. I never studied English in formal education, so basically taught myself. I think I tried my best – at the beginning I was very quiet, but now I feel more confident. At an academic level I felt well. I realized we might struggle with resources in Uruguay, but certainly not with intellectual capacity. I have never felt discriminated against. I reckon this depends a lot on where you go to.

Who are your scientific role models (both Uruguayan and foreign)?

My mentor (Jose Sotelo Silveira) is a role model – I’ve known him longer than I have known very important people in my life, for example my wife 🙂 , I have worked with him for 10 years, and I have tried to learn and acquire his best qualities. And I avoid repeating any faults I see. We all have qualities and defects. The mode of work that Dr. Federico Dajas Bailador had was great. I think he’s both proactive and practical – the meetings with him were very objective, so they weren’t these endless useless meetings. I then worked in Canada with Dr. Thomas Kislinger, who was also extremely efficient. And finally Dr. Leonel Malacrida. I think he’s great, and what he is trying to do in the region is completely out of the ordinary. Leonel has a lot of experience in an area that is a bit missing here – and he has a lack of personnel. So he has the additional task of establishing these tools from scratch, but he has been facing these challenges fearlessly. Altogether, I’ve tried to learn from the best qualities from all of them.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Uruguay, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I have always had colleagues who are women. I believe gender gaps transcend beyond science, and permeates all careers. In Uruguay, over 50% of junior scientists are women, but this percentage falls to very low levels in positions of leadership. This is where the problem lies! To me it’s clear this is not due to lack of capacity, but a gender gap based on biases and a glass ceiling that are gender-specific. Moreover, there are cultural stereotypes of what are careers of suitable for men and women, and these biases and stereotypes are very difficult to break. But I think we are progressing very slowly in trying to tackle this and make it clear that all careers are available for everyone regardless of gender. There was a plan, the plan CEIBAL, that started 15 years ago, which ensured that all children had access to a computer in Uruguay, independent of their socio-economic status. Many of the kids brought up under this concept are now adults, and this led a difference for example in the number of women coding and computer science-related careers. Overall I think this is a world-wide problem though. I reckon Uruguay is just average related to most of the rest of the world.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

I love fluorescence microscopy. Nowadays I am into super-resolution microscopy, and trying to establish it in the country. Since I am trying to build equipment that allows us to do STORM here, I see it as my ‘baby’- I feel very involved. I am trying to establish in particular DNA-PAINT, and I am enjoying it a lot. This would be the first equipment for super-resolution in Uruguay.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

In general, my interest for super-resolution microscopy started when the Nobel prize was awarded for breaking the diffraction limit. I was a young scientist at the time and this to me was extraordinary. In parallel I worked on protein synthesis in axons and this is a topic of huge interest- there is a lot of controversy around this topic, with some people focusing solely in dendrites. So during my work we followed protein synthesis in various regions. Seeing the fluorescent signal of local protein synthesis in axons, was extraordinary for me.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Uruguayan scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

This is a difficult question. A hybrid position like mine is tricky. My advise is, if you like versatility and having a new way of thinking this is key. Do this. If you don’t like this juggling, then look to establish yourself in either of both career paths. At this point, one difficulty is to explain to others what exactly it is that you do: not many people understand the nature of hybrid positions. Another thing I must say is that if your interest is in having a good income, this career is really not the right one: either in the short term or the long term…. There’s really no financial security. Hopefully this changes, but this is the reality at the moment. I think you should manage this expectation very well.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Uruguay, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think Uruguay is complex: Uruguay is a country that has difficulty in establishing state policies: policies that transcend time: they are all government-dependent, and so when a government changes many policies (including those affecting science and technology) don’t survive these changes. I think Uruguay has a lot of capable human resources in various areas including science, technology, computing science, etc. There are areas of research that are progressing quickly. I hope microscopy will face a similar progress. I think influence like the one Leonel Malacrida is bringing will make a difference, and the same is true of the networks that are being formed. External funding like the Chan Zuckenberg Initiative and other fellowships are also playing a role in increasing the capacity in the country. Science in Uruguay moves a bit slowly, but it always moves forward. I have great hoped for the future of Uruguay and Latin America in general.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Uruguay a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

Food is fantastic. If you come to Uruguay, you have to eat an ‘asado’. Uruguay is also very versatile in terms of what you can do. Despite being a small country, there’s something for all tastes: there’s thermal baths, beaches, trails for hiking, cultural activities, and so on. In terms of science, also despite being a small country, our scientific community is very friendly and very capable. It’s easy to learn things and network. You will have direct contact with people and with things because it’s a small country.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)