An interview with Dario Fernando Cueva Granda

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 27 June 2023

MiniBio: Dario Cueva is a MSc student at Universidad de San Francisco de Quito, working on biofilms in the lab of Prof. Antonio Machado (also interviewed in this series). Dario studied Biotechnology at the same university. He has used light and electron microscopy to study biofilms and bacteriophages. In this interview he tells us about his work on various topics ranging from bear biodiversity, to Marine Biology; his collaborative work in the Galapagos islands, and his international collaborations. Moreover, he speaks about the context of science in Ecuador, and his hopes for the future of research in his country.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I grew up in Ecuador in a town in the Amazon, called Nueva Loja or Lago Agrio – its main activity is petroleum production. The landscapes around this town are beautiful, but since I grew up there, whenever people praise how beautiful the landscapes are in Ecuador, for me this was my day-to-day. At school, during high school, I specialized in Mathematics and Physics. At the time I hadn’t envisioned studying Biology. When the time came to choose what undergraduate degree to study, the government opened a website compiling all the degrees offered in all Universities across the country. I found the degree of Biotechnology at Universidad de San Francisco de Quito, which is where I currently work. I liked it because it combined multiple disciplines in one degree from Physics to Mathematics, Environmental Engineering, Chemical Engineering, Industrial Engineering, Biomedical sciences, and Medicine. I found this syllabus interesting because I loved all those topics, and I did not know which one to choose. As an undergraduate student, I joined Dr. Antonio Machado’s lab for a project. His Ph.D. focused on studying bacteria that adhere to the vaginal epithelium – this involves a lot of microscopy techniques, which he explored and mastered. When I was an undergraduate student, he had just joined the faculty as a professor after finishing his Ph.D. in Portugal. I found his projects interesting. After finishing my undergraduate I went abroad to work and then came back to do my postgraduate studies with Antonio. For me, research is fascinating because for a brief moment in time, only you know something that no one else in the world knows.

You have a career-long involvement in biofilms and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

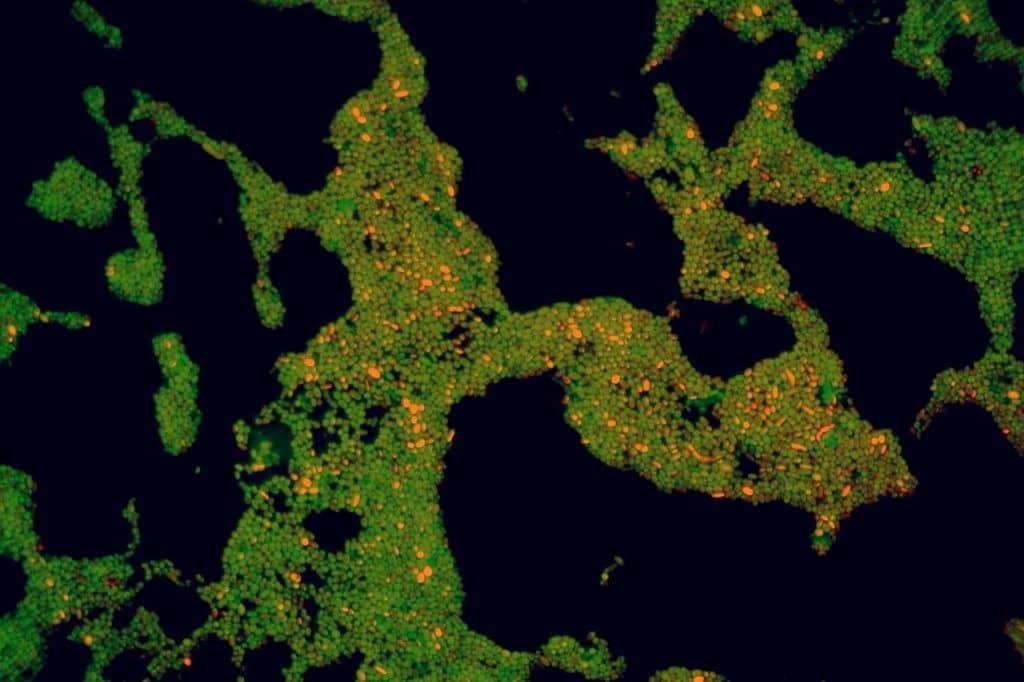

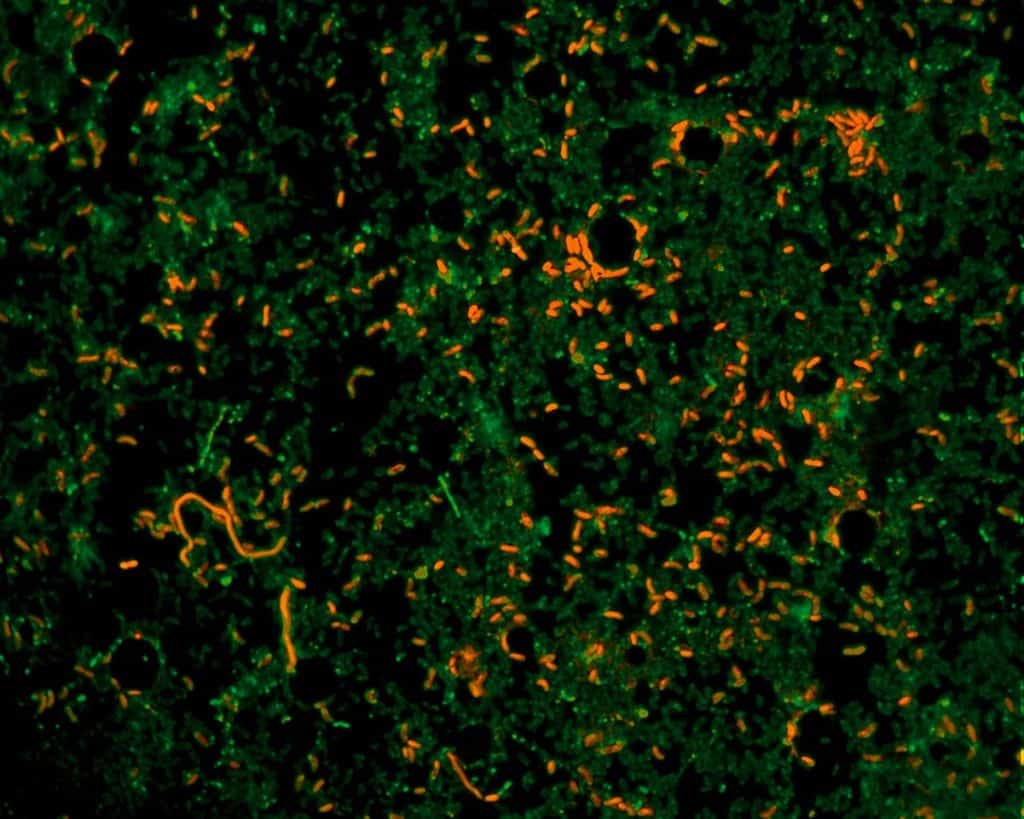

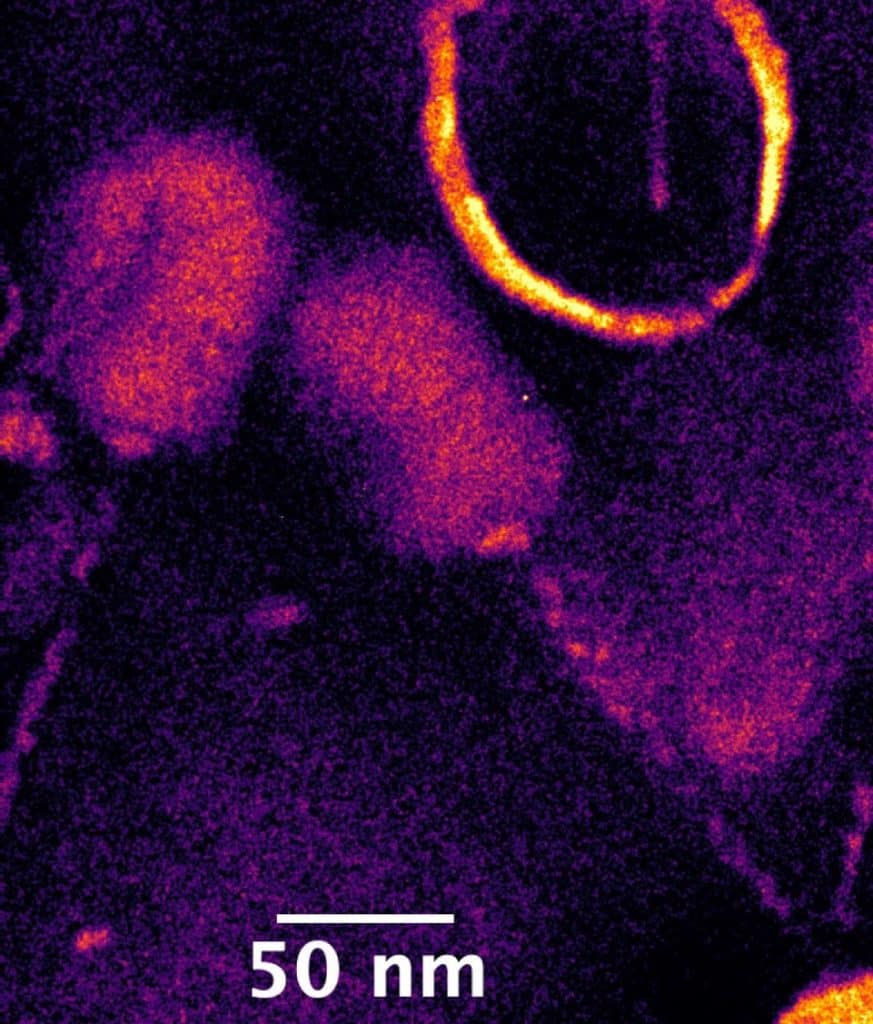

I did my MSc at the Institute of Microbiology at the University (at Universidad de San Francisco de Quito), and here it’s up to the student to choose a project, so I chose to work with Antonio to study biofilms using a broad range of techniques. During my undergraduate degree, I had used mostly molecular tools, so when I started my postgraduate, Antonio had begun to explore other techniques such as microscopy, to address research questions. He had more active collaborations and was doing a bunch of new things I had never heard of. I was a bit intimidated initially, about this whole new set of tools and a world I didn’t really know. Within Microbiology, we work on biofilms – communities formed by bacteria – it’s very interesting to study them from a structural point of view. So microscopy is a pivotal tool – without it, you can’t study a lot about biofilm structure. For fluorescence microscopy, we use differential dyes (Dead/Live) to study mortality rates within the biofilms, and later used SEM and confocal microscopy to explore their behavior, and structure changes over time. We are also interested in knowing how different drug treatments impact bacterial units within biofilms – overall viability. It’s a bit of a learning curve though in microscopy! You need to spend many hours in a dark room, perfecting the ability to focus the bacteria without bleaching them or affecting them with light. Once you master it, it’s good fun. I’ll share some of the images we’ve acquired with you! Some biofilms were impossible to see by microscopy – they were so dense that everything looked like one huge dense blanket. We had to ultrasonicate the biofilm to separate the cells, dilute them, and stain them to be able to visualize them. My MSc thesis involved working with bacteriophages as well, so we required the use of transmission electron microscopy. Again, a lot of struggle and a very steep learning curve of how to prepare the samples just right. Yet, the results are very satisfying.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Ecuador, from your education years?

Ecuador has given me lots of opportunities. To begin with, education is free at all levels. I attended a public school for instance. I feel the education I received at a small town in the Amazon was very good, even compared to other elite private schools in the capital of Ecuador. What I do feel is that there is a misconception that public school is not good, and this comes from the fact that most people attending public schools come from low socio-economic backgrounds. Children may be malnourished, or absenteeism is prevalent due to health or socio-economic issues, so this prejudice and disparity between public and private schools is based on this, rather than on academic quality. I was lucky to have a very supportive family who made sure that I had everything I needed for my studies. I also had the chance to study at Universidad de San Francisco, which is a private University. I got a scholarship to study for my undergraduate degree here, and I didn’t feel there was a difference compared to my other colleagues who studied their high school and basic education in private schools. The environment here is great – the treatment among us and with our professors is very horizontal. I’ve had a huge amount of opportunities to work on various projects, collaborate with various researchers, publish, and learn a huge amount of technical and practical skills. So, I’m eternally grateful to my University and my professors. This is the philosophy of liberal arts in this University, where they support experimentation and intellectual freedom – they make it easy for one to learn and explore. So, altogether, I’m grateful to Ecuador for the opportunities it has given me.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a MSc student-researcher at Universidad de San Francisco de Quito?

My day-to-day is currently a bit relaxed, but usually, I don’t have a very rigid routine. Classes as an MSc student usually start at 10 am, but when I was an undergraduate they started at 7 am. So now I usually have a very productive morning, and I plan my day at the lab. The experiments with biofilms are complex and really long, so it requires a good amount of planning. At the beginning, I used to think that IFAs of biofilms should be imaged immediately so I would prepare my biofilms from say, 10 am to 4 pm, and then I would stay imaging from 4 pm to 10 pm. Now I know that one can store IFAs and image them the next day or after! Something I learned from Antonio, and the dynamics of his lab is that he always had volunteer students – people working with him are not just his students (who have a commitment to finish a project), but interns who are fully interested in the topic. So now my duties involve teaching, which I think is great – I think it’s motivating to play a role in awakening the interest and curiosity of younger students for science. There are some weeks that are very tiring, and some which are relaxed which give us time for planning and thinking and reading. I think it’s important to find a balance, to prevent a burnout both in myself and in the students I supervise.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Ecuador?

I haven’t really. I have worked with non-Latin American foreigners though. But this is due to how the University’s philosophy is – it’s very well connected to labs in Europe and the USA. I’m part of a project trying to better describe algae communities in the Galapagos islands. This involves morphological analysis as well as genomic analyses. Every researcher’s dream in the field of Marine Biology is to work in the Galapagos islands, and I am lucky that my university has these links, and I am able to do so. I’m collaborating with researchers in North Carolina in Chapel Hill USA, and with researchers from Manchester in the UK. Another project I was involved in was in population genetics of bears, where we tried to establish collaborations with other Latin American scientists, but they did not happen. In my experience, in some fields, people are reluctant to collaborate and/or share expertise. This might be due to the already difficult conditions in which science is done in the region which of course include a lack of resources.

Who are your scientific role models (both Ecuadorian and foreign)?

In this sense I try to not idealize people because you know the saying: never meet your heroes. In terms of work, I admire though, right now there’s the work from Frédérique Le Roux, a French scientist focusing on population dynamics of bacteriophages and how they affect bacteria in oceans or culture systems. All the techniques her team is using are super interesting, as are the findings and research questions they’re addressing, including for example exploring why a specific bacteriophage infects a specific bacterium but not another, if one is derived from the other. For me, it’s very interesting because all we know from lab studies doesn’t always apply to natural populations. There are too many variables in natural populations: populations are not clonal, and more than one phage co-exists with more than one bacterial population, so it’s all much more complicated than our minimalistic version in the labs. So, the Le Roux lab investigates this variability. I will be lucky to meet her in 3 weeks, at a school for Marine Biology that will take place at the Center of Marine Biology CENAIM from ESPOL University on the coast of Ecuador. (Update! I met her and she is Amazing! She was impressively smart and knowledgeable, and very fun to chat with. She was the favorite lecturer among the Ecuadorian and Latin American students that attended the event. Everyone just wanted a picture with her and commented about how nice she had been). Other than the work by Prof. Le Roux, another work I admire is that of Prof. Doudna and Prof. Charpentier, the pioneers of CRISPR gene editing. Since 2013 when CRISPR research began, molecular biology has experienced a revolution, so it’s impossible not to recognize those major contributions, especially as they apply to an immense amount of fields, including personalized medicine, which should allow us to treat diseases that are currently untreatable. In Ecuador, I admire researchers in general – Ecuador is a small country, but the scientific community is even smaller. My university hosts about 50% of people with doctorate degrees in the country. One researcher I admire a lot is Prof. Maria de Lourdes Torres who founded the syllabus of Biotechnology at my university. She specializes in the topic of transgenics, their regulation, and experimental molecular biology. She is at that frontier where science meets reality, including topics of legislation and biosecurity. Someone who leads those topics I think does admirable work, especially in Latin America, where bureaucracies and politics are a big barrier for scientific progress.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Ecuador, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

Within the University I am, I don’t feel there are a lot of imbalances. For me, personally, you asked me who are my heroes, and if you notice all of them are women. I have been lucky to be surrounded by brilliant women in academia. I think in academia, in my reality, the topic of gender imbalance dissipates – I think we are often judged for our capacities as researchers, and when people are given the chance of demonstrating what they are capable of those “disparity” lines blur. Yet, that is my perception, and I cannot provide further comments on how it might be on the inside. However, in my opinion, one of the main problems in academia is attracting women to science, mostly because in the early education for boys and girls, there are still a lot of stereotypes on what a girl and a boy can or should study – boys are still encouraged to pursue technology and science, while girls are encouraged to pursue nursing, and other “caring” related professions. This should change of course, but this interest needs to be nurtured at an early age in an equal manner for all genders.

Are there any historical events in Ecuador that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

Ecuador is actually the first country in the region where women fought for and won the right to vote. In terms of science, I can’t think of a unique event that has altered the course of science. There’s always a struggle between science and politics. The Government didn’t want to recognize private Universities in Ecuador, to begin with, so there’s a struggle in this regard. In terms of science, my feeling is that it’s becoming more and more cumbersome to do science in the country. In 2007, we had a new Constitution in the country. There are many interesting things in our Constitution, for example, the Constitution recognizes the rights of nature. From this point, there is legislation to preserve and protect the natural world. I think this is super important and valuable. But there are other things that heavily restrict scientific research, for example, there is an article that forbids transgenic cultures, unless they are of national interest and approved by the National Assembly (members of Congress in Ecuador). So, if we want to develop a GMO, it will never leave the lab. We know now that GMOs are not the problem (from a technical point of view), but the perception and the practices associated with them, like monopolies over seeds, herbicides, extensive monocultures, etc. Our range of applications is fully restricted. To give you some context, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru are part of the Comunidad Andina de Naciones (the Andean Community) which has something called ‘Decision 391’ which is related to genetic resources – it regulates how scientists can use the biodiversity in our reach, to generate products and benefits. The 391 is a bloc decision that frames certain topics from the Convention on Biological Diversity CBD. One issue is the definition of a genetic resource. For the CBD, this term “means genetic material of actual or potential value.” While for 391 a genetic resource is “all biological material that contains genetic information of value or of real or potential use”. You see how this change in definition might have a big impact on interpretation. In Ecuador, the interpretation of this decision is very rigid. For example, on the topic of fair distribution of benefits derived from access to resources, there is a Code (COESCCI) that establishes that at least 50% of the benefits should come to the government. In Ecuador, if I want to use the resource for some application, I have to submit a contract with the State, acknowledging that the resources belong to the State, and regulating how any profit will then be distributed back to the State (among other beneficiaries). But, Ecuador’s stance is much more prohibitive than that – for example already to do biodiversity studies on a natural resource, I would have to submit a contract. So, it’s a major bureaucratic process. We are super biodiverse, but we can’t do studies on biodiversity without major bureaucracy! I know there are reasons behind this, yet the laws regarding who is the entity responsible for granting the permits are not even that clear. There is a ruling from 2011 that grant those functions to the Ministry of Environment, and the COESCCI from 2016 states that those functions are the responsibility of the State Department of Higher Education, Science, Technology, and Innovation. Both laws are in force, and somehow things work, and from what I have heard, these permits now are much faster to obtain nowadays. So, I hope things go for the better. This all has an origin, of course, to prevent foreign exploitation of our resources. Some years ago, an American expedition (organized by a pharmaceutical) came to the country and took some biodiversity, as part of an agreement with a local public University. At that time there were no regulations, so we can’t really say this was bio-piracy – not from a legal point of view, though it was so from an ethical point of view. I think this was the source of Decision 391 and Ecuador’s hard stance in this respect. These regulations are about 15-20 years old. They aim to protect our resources, but indeed make it complicated to work. Anyway, a downside is that if you’re a foreign scientist who wants to collaborate, Ecuador is perhaps not the most attractive place – you might prefer to go elsewhere where their legislations are more forgiving.

Ecuador has developed scientifically, from the creation of private universities. This is also mostly because public education is regulated by the State, so everything done in public universities involves decisions of the State. Any purchase is considered a purchase of the State, so you can imagine the bureaucratic labyrinth it can become. Private universities don’t deal with any of this. If a PI from a private University is awarded a grant to acquire equipment or develop a research line, they can purchase equipment or resources from wherever in the world they want. Conversely, the union of public universities to the State has acted as a brake for scientific development. Yet, it is not all bad. Of course public universities and the free access to higher education they provide benefit thousands of people in the country who might not be able to receive an education otherwise. So, they have a very important role in the development of the country.

Recently I found out that the Ecuadorian government is implementing new regulations for the acquisition of materials considered dangerous. For example now, to buy certain reagents which did not have regulations before we will require special permission from the Ecuadorian army. The topic of illegal drugs has become a major priority for the country, but this has impacted science too since now chemical reagents have more regulations. Compared to our neighbors like Colombia, I feel we are falling behind in scientific progress.

Something to add is the SENESCYT scholarships/fellowships during President Correa, which have had an enormous impact on science development. It allowed Ecuadorian scientists to go abroad and gain knowledge and expertise that they could bring back to the country. At the same time, these fellowships require the awardees to return to the country for twice the amount of time that they worked abroad. While this is meant to prevent brain drain, I’m not yet sure how successful this has been since now some people who benefited from those programs are starting to leave the country again or wishing to do so, but I still acknowledge that the program itself has had a huge impact on scientific development in the country.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Ecuador?

No, I’ve never lived abroad. I have friends who have studied abroad, and we’ve discussed differences between doing research in the Global North versus the Global South.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

Interesting question! For now, TEM! When I saw phages for the first time, I was super excited, I can’t even convey the emotion. Especially because it took me months to get a picture. Not even a good one, just an image at all. I find that in EM, there’s a gap in the knowledge of microscope operation vs. biology. No one ever told me about the tricks for sample preparation. I thought that a diluted sample (if we can call it a sample of 1e9 virus per mL as “diluted”) would work, and it didn’t, so it took me months of reading. People don’t report specifics of their methods in their papers so for someone starting in a specific discipline or technique, it’s hard to figure it out, especially if the expertise doesn’t already exist in the lab. So, when I was able to see the phages, after months of work (and after figuring out how to concentrate the phages to 1e12 – yes, one trillion viral particles per mL), I was thrilled.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

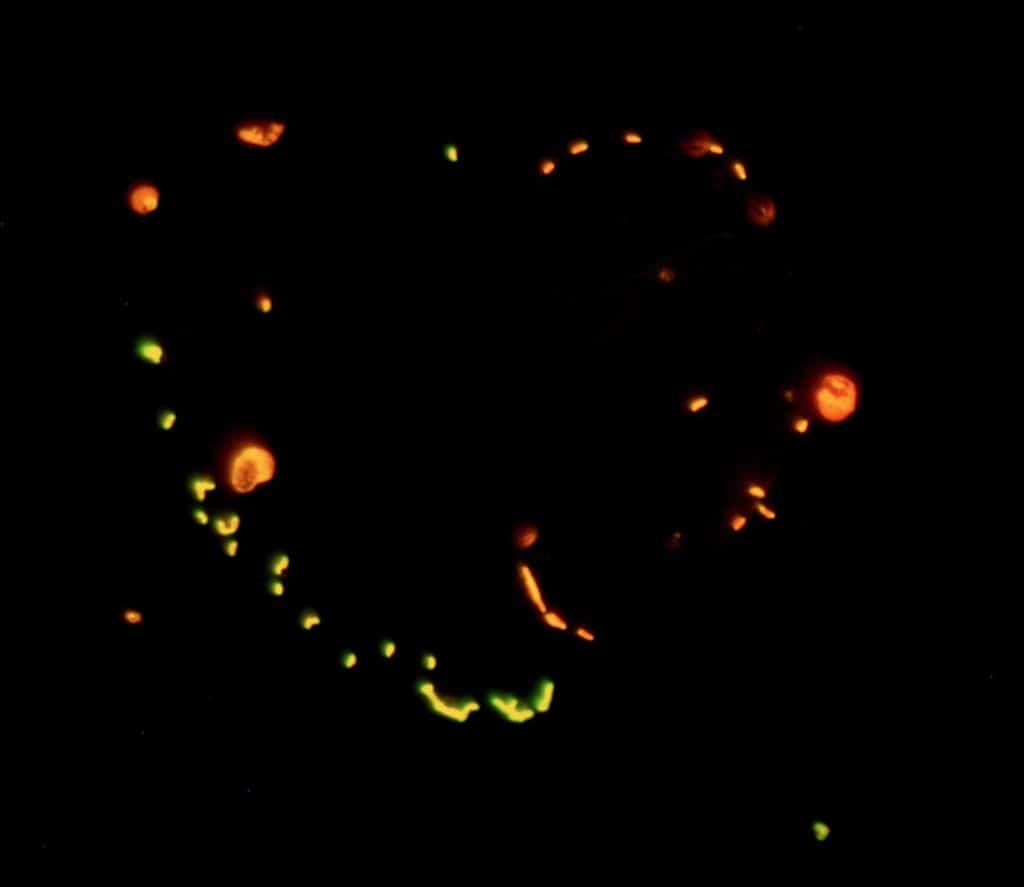

My phages 🙂 and the heart I found by fluorescence microscopy (actually, one of the undergrad students that worked with me, Nicolás Jara, found it) -I’ll share the image with you. Or two phages interacting with one another – I’ll also share those images.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Ecuadorian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Don’t believe everything you’re told. To become a scientist, you need to be curious, and you should have initiative. This is what science is at the end of the day: to build upon the knowledge of others with your own interests and passion. You should find this – what are you passionate about and be proactive: proactive to generate questions, troubleshoot, and so on. Science is a difficult career; it is not like in science fiction books or like in some science communication programs. It is way more complicated. Some people devote their lives just to figuring a problem out. If you don’t have or develop these skills, you’ll find science a frustrating profession.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Ecuador, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think there’s plenty of room for improvement. We have very few high-end microscopes in the country. My university has one of the very few SEMs in the country, and they mainly use it for material science which is one of the things they excel at. I know we are now starting to consider doing other types of microscopy. I think my University is committed to scientific progress- I found out that they are considering acquiring a confocal microscope. But, for the TEM analysis, I have had to use the facilities of other universities as we do not currently have it. I think many people in the country think that microscopes are only for diagnosis, and don’t know the scope of microscopes that exist and their potential. So, the narrative needs to change, to shift this idea that microscopes are only useful for pretty pictures or for diagnosis.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Ecuador a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

Its people! We’re all very expressive. People from the coast are easygoing, open, and expressive with their thoughts. I felt very welcomed when I moved there for job opportunities. But we are also a little bit weird, in Quito, by 8 pm people are at home having a hot chocolate, because it’s very cold (for us Ecuadorians at latitude 0). In fact, Humboldt apparently said that “Ecuadorians are strange and unique beings, they sleep peacefully amid smoking volcanoes, they live in poverty amid incomparable wealth and they cheer up with sad music.” So for a long time, foreigners notice that Ecuadorians have a very peculiar character. Beyond this, there’s a lot of talent in the country, and the fact that education is free is an incredible advantage. Neighbouring countries, or other countries from the Global North are often shocked that healthcare and education are both free, granted by the State. Hopefully, we can stop the brain drain and be better able to retain talent as Ecuador develops. Other than that, the Galapagos islands are incredible- a true wonder to behold. It’s very expensive though, but totally worth it.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)