Education Strategies of Imaging Cores

Posted by Daniel Doucet, on 1 April 2024

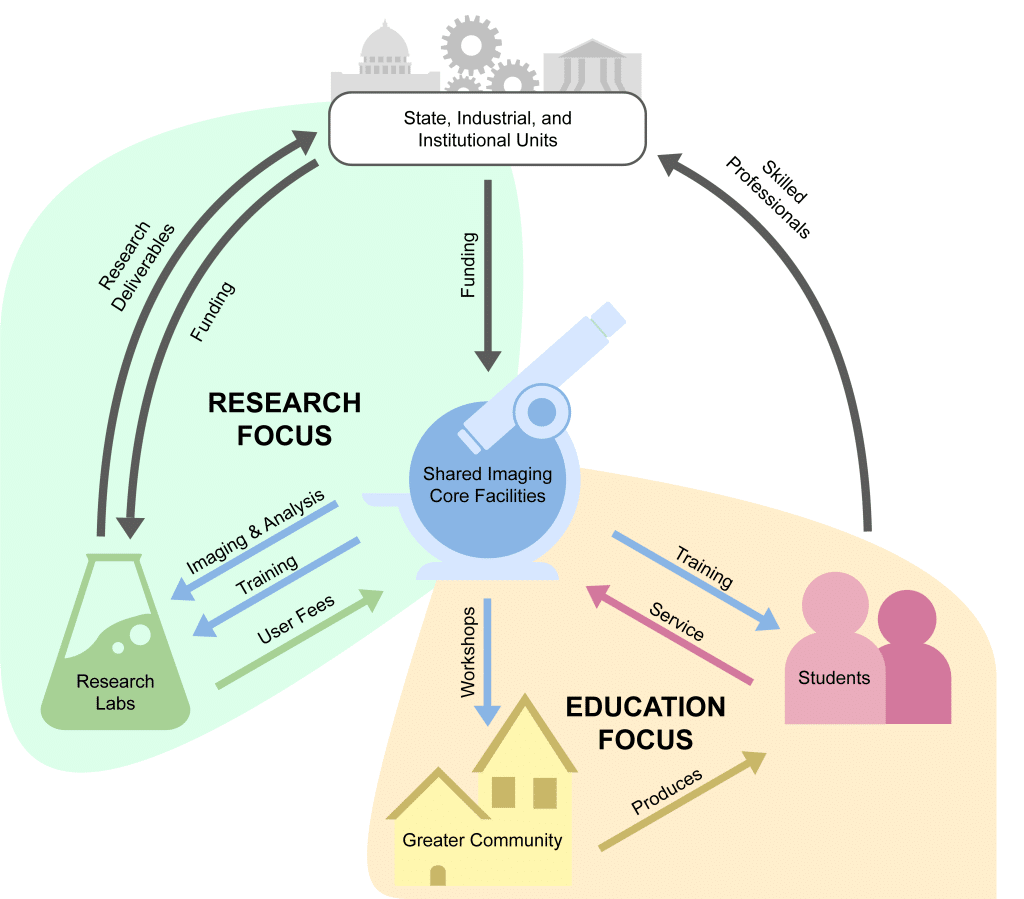

Over the past two decades, high profile research institutions have come to rely on distinct core facilities for much of their data and image analysis. The benefits of the newest technologies are often softened by the costs of purchasing and maintaining such equipment for regular use. For microscopy and imaging, it only made sense that equipment and sample preparation be consolidated to even just a small team of researchers that could better serve a multitude of labs, saving time and money for whole departments and institutions. Whether at teaching or research institutions, education strategies of imaging cores have shifted to accommodate the demand of faculty and students alike.

An article from researchers in the cores of Northwestern University describes facilities as running like small non-profit businesses, detailing four pillars of core sustainability that are crucial for long-term growth (personnel, space, investment, and evaluation). Institutional, federal, and industrial investment is determined by how marketable a core can be – a sum of its production of skilled professionals and research output. Whether for grant proposals or increased internal funding, it is crucial for cores to market their resources. This article presents several strategies that cores are currently considering and implementing to not only address the need for cores to advance beyond simple service facilities, but to best serve the myriad needs of the changing world of STEM education.

Workshops and Short Courses

Due to the niche nature of many imaging core functions, a full-length course is often hard to justify. Increasingly common are workshops and short courses that can take place over a few hours to a single week. These can cover anything from fixation protocols to image analysis software and techniques. Some challenges of creating successful workshops appear from both the attendee and employee sides.

On one hand, cores may find difficulty getting students or faculty interested if they don’t already have a specific project in mind. Students may sign up for a workshop and not show, cutting the morale of the instructor(s) and leading to a lot of prep work that goes to waste. To remedy this, core directors will try to kill two birds with one stone – charge for registration of the workshop. This change compensates the core for the resources being devoted to the workshop. The drawback is a limited attendance simply due to the price tag behind it, where many students (without faculty support) simply won’t register. As an olive branch, many cores have made registration payments count towards future imaging or sample prep, or may grant a discount on projects associated with the workshop’s content. Either concession would encourage subsequent use of the facility. (be sure to check out our events page to stay up to date with both in-person and online workshops being offered!)

Alternatively, design and implementation of courses can be limited by core resources. Core scientists and technicians are busy. Devoting time to designing an effective and engaging course, even one that only lasts a few hours, can be difficult to accomplish – especially as something that isn’t part of an employee’s immediate responsibilities. This is an opportunity to bring in experienced graduate students on course development and running the workshop. Besides a nice addition to their CV, students will learn more by being involved with delivering course material. Additionally, many cores are taking advantage of online materials to make lasting resources for their students and faculty (see Microscopy Australia).

Mentoring Model

As grant funding moves to favoring proposals with a collaborative, or ‘interdisciplinary’ spin to their work, there is continued need to market core facilities as a melting pot of STEM research. Microscopy and imaging facilities are consistently areas where materials science or biological and medical research is met with a proper understanding of chemistry and physics – all enabled by the software behind the instruments and data analysis. Taking advantage of this blend of research professionals from differing fields, an example program out of Harvard Medical School has used their core facility to train postdoc students.

Although mentoring students within an imaging core would primarily focus on instrument training and competency with sample prep/data analysis, students would (in varying ways, depending on the university) graduate these programs with significant interdisciplinary experience. It isn’t unusual for cores to work with materials scientists and biologists in the same day!

Mentoring, though a greater investment than a short course, offers more consistent return as students develop skills necessary to routine core functions. Out of all the education strategies of imaging cores, internships and mentoring models offer the greatest flexibility. Successfully mentored students, in addition to increasing marketability of the core within the institution, may go on to work for the private sector – potentially developing or strengthening relationships between core facilities and industry. Such partnerships could be essential in the future (should grant funding be inconsistent) as industry benefits from highly educated and technically proficient graduates. These students may also be a great demographic for future core researchers and technicians, already familiar with the workings of an institution and at home in its culture.

Community Involvement

Although core facilities will continue to primarily function in research, partnering with primary education and industry is increasingly common for cores.

Industry can assist cores with equipment and financial benefits that otherwise would only be possible with competitive grants. Several industry giants (Nikon, Leica, Zeiss) have sponsored core facilities to varying degrees, while others give discounts to facilities with multiples of their instruments. Outside of obviously microscopy manufacturers, other industry in oil and gas, forensics, and engineering can benefit from several instruments found in the typical imaging core. Collaborating with the private sector can help train students with marketplace-relevant samples to prepare them for a career outside academia, should they desire to pursue it.

But long before students look through career paths that require instrument specialty, they’re looking through a brightfield microscope at a primary school. The quality of STEM primary education varies greatly around the world, even within a single urban area. Due to this, many students arrive in higher education with nothing but a rudimentary understanding of microscopes. Even still, introductory classes at university may spend all of five minutes teaching students the basics (e.g. how to not scratch the 40x objective lens). Collaborative events with primary schools attempt to improve young students’ familiarity with microscopes and allow core facilities to serve their community outside of typical research activities.

From personal experience, our own workshops with students ages 8 to 18 have involved the intersection of art and science. Students were able to view life microscopically and illustrate based on the slides available (among other activities to keep them interested!). These were wonderful opportunities to give enrichment to kids of different backgrounds, as well as a chance to partner with other departments on campus we wouldn’t typically work with. Younger students are surprisingly eager to understand what they’re looking at under the scope, and I don’t imagine most adults are any different – implementing varied education strategies through imaging cores can bring out that same curiosity.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)