From Microscope to Macro-Scope: Same Sobek, New Glyphs

Posted by Daniel Doucet, on 5 September 2024

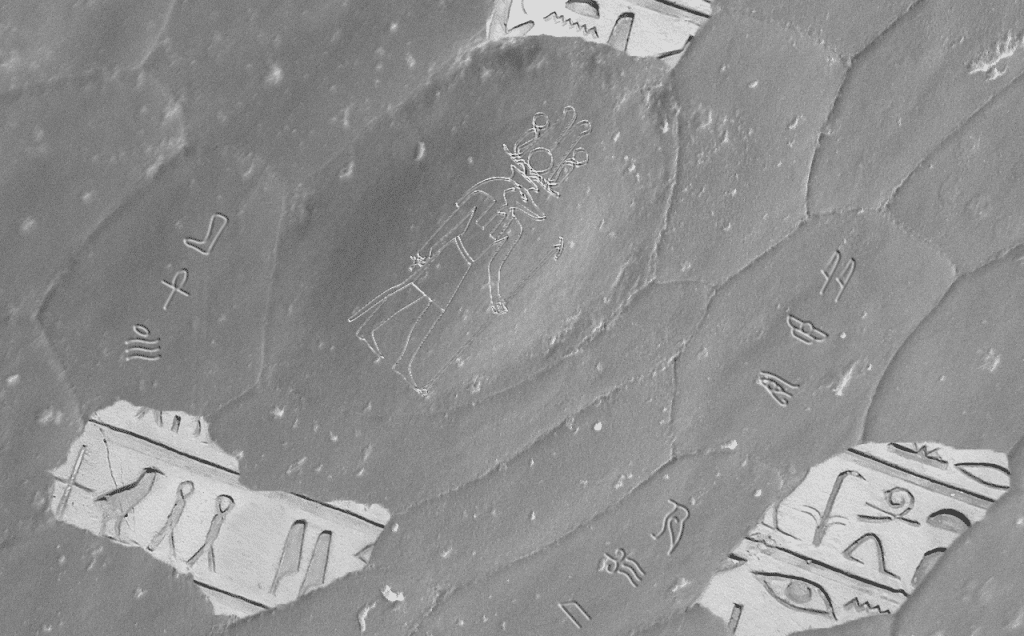

Thousands of years ago, the Ancient Egyptians depicted their numerous gods on hieroglyphics. One of which is an amalgamation of crocodile and man – Sobek, the god of the Nile River. These sacred carvings (from the classical Greek “heiros”, sacred; “glyphikos”, carving) have to be deciphered carefully by historians who are far removed from the culture that produced these artifacts.

Parallel to this, biologists time and time again find themselves far removed from understanding an artifact in the morphology of soft tissue or bone. Useful data from phylogenetic trees and homologous structures may give some explanation as to whether a structure is vestigial or not, though this is increasingly rare as we move to the microscopic scale where hypotheses become difficult to test.

Brief Context

In the 1970s, when scanning electron microscopy had just begun to be available for biological research, glyphs appeared at a scale previously unobservable. Herpetologists, interested in the biology of reptiles and amphibians, have seen a wide variety of microstructures (sometimes named very literally “microdermatoglyphs”). As technology has advanced in the past 50 years, experts have developed novel methods to overcome the barrier of understanding microscopic morphologies. Just as historians compile data so that hieroglyphics may be deciphered, disparate methods used in conjunction with light or electron microscopy can remedy confusions of the first impression.

Early works remain important for laying the groundwork of understanding structures and their relationship to reptile biology. Select snake specimens from Gans and Baic suggest friction as a motivating force to microstructure specialization (Gans and Baic 1977). At the time, no methods could accurately determine such force. As early as 1999 (Hazel et al 1999) – and even recently (Baum et al 2014) – Atomic Force Microscopy was applied to visualize friction signal of these microstructures, giving credence to the hypotheticals proposed 20+ years earlier.

One complication that continually arose in researching these glyphs was the biology of lizard and snake integument. In examining scales through electron microscopy alone (using secondary electron detectors), researchers could only be sure of morphological features on the most external layer of the scale – named the oberhäutchen. Apparent cell divisions and abundance of glyphs and patterns that appear on the oberhäutchen can often be misleading (Irish et al 1988, Harvey 1993, Harvey and Gutbertlet 1995). This is attributed to the regular shedding and growth of these critters, which often disrupts replicability.

Recent Efforts

To overcome these limitations, comparing species habitation and locomotive capabilities grants a better context to the glyph shape and abundance (Rocha-Barbosa and Moraes e Silva 2009, Riedel et al 2019). The implementation of histological techniques can also grant critical information. In many cases these strange formations, follicles, or pits might indicate something more than mere keratinized skin when imaging the Oberhautchen through SEM – and several studies have taken pains to identify what physiological mechanisms are present in these structures (Chang et al 2009, Dujsebayeva et al 2021, Kandyel et al 2021). As early as 1913 (Schmidt 1913), cross sections of lizard scales were examined to identify variation in these sensory structures. Even today, much remains to be told on the phylogenetic importance of the scale surface and these strange microstructures.

The sheer amount of time it takes to apply even one type of microscopy mentioned (SEM, AFM, thin sectioning and staining, etc) in any systematic fashion leaves many of these studies focused on only a handful of species. Occasionally an investigation will spread the breadth of an entire group, such as Bezy and Peterson’s iguanid microstructure survey (1984), or similar investigation into cordylid and gerrhosaurid lizards from Harvey and Gutbertlet (1995). Application of high-resolution micro-CT data can do tremendous work at visualizing structures at increasingly high magnifications. Hopes of more thorough analysis of these cold-blooded creature skins will carry researchers into the next chapter of microstructure decrypting. Soon, just as the heiroglyphics on ancient tablets and walls were slowly understood – herpetologists may understand better how these carvings appeared… and what they might be trying to tell us!

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)