An interview with Marcel Cunha

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 26 April 2022

MiniBio: Marcel Cunha is currently an adjunct professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). He started his career during a BSc degree in Microbiology and Immunology at UFRJ. He then joined Instituto de Biofisica Carlos Chagas Filho (UFRJ) to do his MSc and PhD studies. Later he did his postdoc in Institut Curie (Orsay) in France. He has great expertise in electron microscopy and mycology.

Brazil has a long-standing history of contributions to science both, in Latin America and world-wide. It is the land of scientists as renowned as Carlos Chagas and Oswaldo Cruz. It is also a country of fascinating biodiversity, attractive the whole world around. Before becoming a scientist, were you aware of this heritage? What inspired you to become a scientist?

Yes, we learn about Carlos Chagas and Oswaldo Cruz from our early school years. Those names are very present in the everyday life of science and public health. In Rio de Janeiro, we have the Oswaldo Cruz foundation as one of the greatest public health institutes. At various points of one’s career, one comes across these names. Carlos Chagas gave his name to a very well-known disease in our world region. So, his name is also very well known. It’s easy to identify famous scientists from Brazil. It was exciting for me after I began my career, to realize that many Brazilian scientists, even contemporary to me, are pretty famous in the scientific world, and well esteemed.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy and infectious diseases. What inspired you to choose this career path?

I was always a big fan of technology and science, since I was very young. But there were many things that helped me along the way. I was always very close to science within my family. I had access to science related magazines like National Geographic. I also have an uncle who is a biologist, and he always explained things about nature. I ended up specializing on biotechnology in high-school, and this was decisive to my career. About microscopy and infectious diseases – I was always attracted to this. What became clear to me, was that I was extremely interested in fungi. This was a bit unexpected because early in my career I wasn’t all that interested in fungi. I was interested in viruses. But I did an internship, and once I discovered the potential and function of these beings, was extraordinary. Other than a postdoc I did in cell biology, I’ve dedicated my whole career to understanding fungi. I now work in medical mycology, and more recently in fungi of biotechnological relevance.

You are now a group leader at UFRJ. Can you tell us a bit about your job, and how microscopy plays a role in your day to day work?

My research is only a fraction of what I do, and of my routine. An important part of my routine is to teach (at undergraduate and postgraduate levels), and another part is administration – I am currently coordinator of a Biophysics course, and I am an academic director too. So, over the last two years, I have dedicated a lot to this latter point, especially due to the pandemic. Yet another fraction of my work is scientific outreach. Our goal is that science reaches people who have no access to science and/or university. We work with the local community, also with communities that are not so local, with industry and with children in school years. We teach them about science. We want to build a community linked to science. The University aims to have its doors open to everyone, to come close to science, and within microscopy. I feel microscopy plays an important role in all these spheres I am involved in. As a teacher and as a director, I need to make sure that our microscopes are in a good state, with proper maintenance, and that our lab is well equipped. For instance, during the COVID pandemic, the microscopes used for classes were not in routine use but needed care too. In my classes to undergraduates and postgraduates, I teach students about microscopy, not just microbiology. If for instance I teach about a pathogen, I also show the related microscopy and the basic principles of that specific microscopy technique. I also organize experimental classes where microscopy is an important component, and students get to see their cells of interest by themselves. In terms of coming close to the community, a class that I give as an outreach project is ‘how to make craft beer’. It’s an easy way to explain science a technology related to a topic that many people like and appreciate. And one of the classes is in fact to look down the microscope at the yeast involved in the fermentation of beer. Sometimes this is the first contact of people between 30-50 years of age with microscopy, and this for me is very rewarding. It allows people to use a relatively simple microscope and see things that they have never seen before. In terms of research, microscopy is the main tool I use for my research, which focuses on the use of S. cerevisae for brewing and C. albicans as a pathogen. We use basic to advanced techniques of SEM and TEM. I think a good education in electron microscopy takes a lot of time. But despite the requirement for this huge investment, I have come to realize microscopy does not lose value over time. Perhaps the thought that it loses value was a misconception at some point, and it was a fear I had at some point of my career. This was before super-resolution microscopy, single particle analyses and other techniques brought back the attention to microscopy and were key for many scientific advances. I have seen that the progress of electron microscopy has been constant, and this is very encouraging. There was a point in history where it seemed molecular biology would dominate everything and microscopy would lose its value, but this never happened. Now it is clear that all these tools are complementary to one another.

Regarding your comment on your commitment to scientific outreach, I have two questions. One is, was outreach something that played a role in your own perception of science when you were young? And the second question is whether the initiative for outreach comes from a governmental, institutional, or personal decision?

I was indeed influenced by an initiative of outreach. The science I had access to when I was a young boy was due to scientific outreach initiatives. My mom was a physics teacher in a high-school and she took her students to a museum called “Espaço Ciência Viva”. University professors in the early 1980’s took time and a lot of effort to create this museum. The museum was very simple in terms of resources: it had experiments of acoustics and optics, a few microscopes to be able to observe cells, a few experiments to understand plants and photosynthesis and some other to explain energy of vectors. This alone was already a lot of fun. I remember seeing my own cells under the microscope. And only much later I found out all this concept was established by people who became my teachers at university level. Outreach has brought society closer to science. This initiative has been going on for at least four decades. Specifically in the last 15 years, outreach is a important part of the job of professors at universities, and it is significant for career progression. Outreach is now even part of the undergraduate courses. So it is now an obligation of both, students and professors to engage in outreach – this is at governmental level. It’s a decision based on the fact that society is an important player too. I think outreach has, historically, played a huge role – for example Neil deGrasse Tyson was inspired by Carl Sagan. On everyday life, I have students who reached University because they became inspired in scientific projects they saw as young children. When we build science without taking the general population into consideration, the general population has little idea of what we as scientists do and translates into a hugely negative impact for both.

So, in general, I am greatly committed to outreach. In the course I lead on making craft beer, I had a student who was involved in the construction of the building where I was working (and where this course took place). What he told me was ‘I helped to build this place and had no idea what kind of work was being done here. Now I know what it is for, and I am happy my work was of use’. He himself perceived his own link and value to science in this way.

Throughout your career you have belonged to various world-renowned centres of microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about how this shaped you as a microscopist?

I started thinking about becoming a scientist during high school. Already at this point I went into the area of biotechnology, which I really enjoyed. I then went to do my undergrad in ‘Microbiology and Immunology’. By then I already knew I really liked microorganisms, and there I made a lot of friends. During this time, I went to the lab of Ultraestrutura Celular Herta Mayer – a lab with very high expertise in electron microscopy. At this point I joined the lab of Prof. Sonia Rozental, which focused on mycology. I worked there up to my PhD. In the middle of my PhD I went to Paris to a congress on Medical and Veterinary mycology, and there I spoke to Micologists from Institut Pasteur. They saw my work, and they invited me to do a postdoc in their labs. At the time my partner was also planning to go to France. Sadly around 2008 Institut Pasteur had a reduction in funding and I was unable to join with a fellowship. I ended up joining Institut Curie, to work on a project by Monique Arpin in Prof. Sergio Marco’s Team, and it was a fantastic experience with fantastic people! I applied electron microscopy and models of microvilli. I stayed there in Orsay for 3 years working on electron microscopy. While there, I participated in various conferences and symposia. After this I returned to Brazil to work as a visiting researcher in a couple of temporary positions. After a while there was an open call for UFRJ (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, one of the main universities of Brazil) in 2016 for a position for a parasitology professor, and that’s how I reached my current position. I am very glad to be here – I really love my work J. For me it was great to have shared all my career with excellent microscopists and biologists – it shaped me and my career completely. Moreover, I have been exploring links to industry, and the importance and potential of microscopy in industry too.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Brazil?

In Europe it was very easy to collaborate. I was younger and had a lot of energy. Going to neighbouring cities was easy. In Rio, I am 1 hour away from the central University campus. I am about 2-3 hours away from other cities that hold research facilities in my state, also, my state is the size of Portugal. Now I am considering a collaboration with São Paulo. It is not uncommon in Brazil to have collaborations with other states within Brazil. Regarding Latin America, sadly, I have never had the chance to collaborate with other Latin Americans.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Brazilian researcher, working abroad?

I think when I worked abroad I realized the difficulties of doing science in Brazil. When I was in the USA I noticed that obtaining reagents was much more efficient, and that science was much better funded than it is in Brazil. When I worked in the USA, there were many foreigners in the lab – it was very diverse so it wasn’t very difficult for me to adapt. My experience in the USA was quite peculiar. I think the main challenge of going abroad was that my husband couldn’t join me. It was difficult to be separated during this time. Moreover, there are cultural differences between the USA and Brazil which can be challenging. Nonetheless, as a ‘carioca’ (person native of Rio de Janeiro) I find it easy to communicate with others, so I found it easy to interact with others.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Brazilian researcher, working abroad?

In Brazil, access to reagents is very limited – our currency is very devalued compared to the dollar and the euro, so it is very expensive. Moreover physically, reagents can take a long time to arrive. When I was in France, in Orsay, I would order reagents and would receive them the same week. Right now I am in Rio de Janeiro – so in other more remote places in the country, this is even more difficult. In terms of equipment and maintenance, this is also very difficult. Sometimes the place for maintenance (eg. for a microscope) is in Europe or in Japan. So it is a long story. On the other hand, for the positives, in Brazil we have a huge biodiversity, and a motivation to address local diseases and investigate local biology. Internally we don’t face much competition. This can be a disadvantage, though, in the sense that if we try to publish local research in big journals, this is not interesting for them due to the perceived lack of global impact. Even if the science is excellent. Sometimes I have the impression that Brazilian science is not always valued abroad. I was once in a congress in Berlin where I was shocked: the third largest ‘committee’ was from Brazil, with the first and second largest were Germany and UK. But this was not representative in the oral presentations: most Brazilians were presenting posters only, despite having huge representation at the congress in terms of numbers. Maybe this will change one day, and people will see the relevance of local research for its potential in the future.

You mentioned the topic of publications, journals and open science. Can you expand on this?

Well – recently I saw on Twitter that one of the most prestigious journals was charging over four digits euros for a publication. With that amount of money here in Brazil you can buy a nice car. Moreover, in Brazil our grants do not generally cover publication costs. So we are limited to journals that do not have publication fees. This ‘readout’ that in Europe is extremely valued (namely Nature, Cell and Science papers) is a bit unrealistic. But to compensate, in Brazil it’s not uncommon for students to finish their PhDs with 5 papers, and this is sometimes recognized abroad too.

Who are your scientific role models (both Brazilian and foreign)?

I think I had many and mentioning all by name will be very difficult. I think each role model inspires in a very specific way. I think I didn’t get inspiration just from one person but many. I think my seniors inspired me in many ways: my direct supervisors, Sonia Rozental: I’d love to lead a group as successfully as she did. Wanderley de Souza: he has a political ability that is incredible: he can talk with anyone from any sectors of society. He is very keen to bring science to everyone. I’d love to be like this one day. Outside Brazil, Prof. Bruno Humbel who I think is now in Japan – I’d love to have the same amount of knowledge on microscopy as he does. Prof. Jennifer Lippincott-Schwarz too – I went to a talk that she gave at a symposium on cell biology, and it was spectacular. This type of quality is inspiring, and I would love to one day present the way she did, with the spectacular results and science she presented. Altogether I think there are many more (30 people at least): I won’t be able to make justice to everyone.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

This is a very complicated question. I think the most impactful for everyone’s eyes is SEM – I think from an artistic point of view this is my favorite, despite me thinking that this is the technique that perhaps answers the least amount of questions amongst all the types of microscopy I use J. It’s the least elaborate, but brings joy to everyone’s hearts.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An ‘eureka’ moment for you?

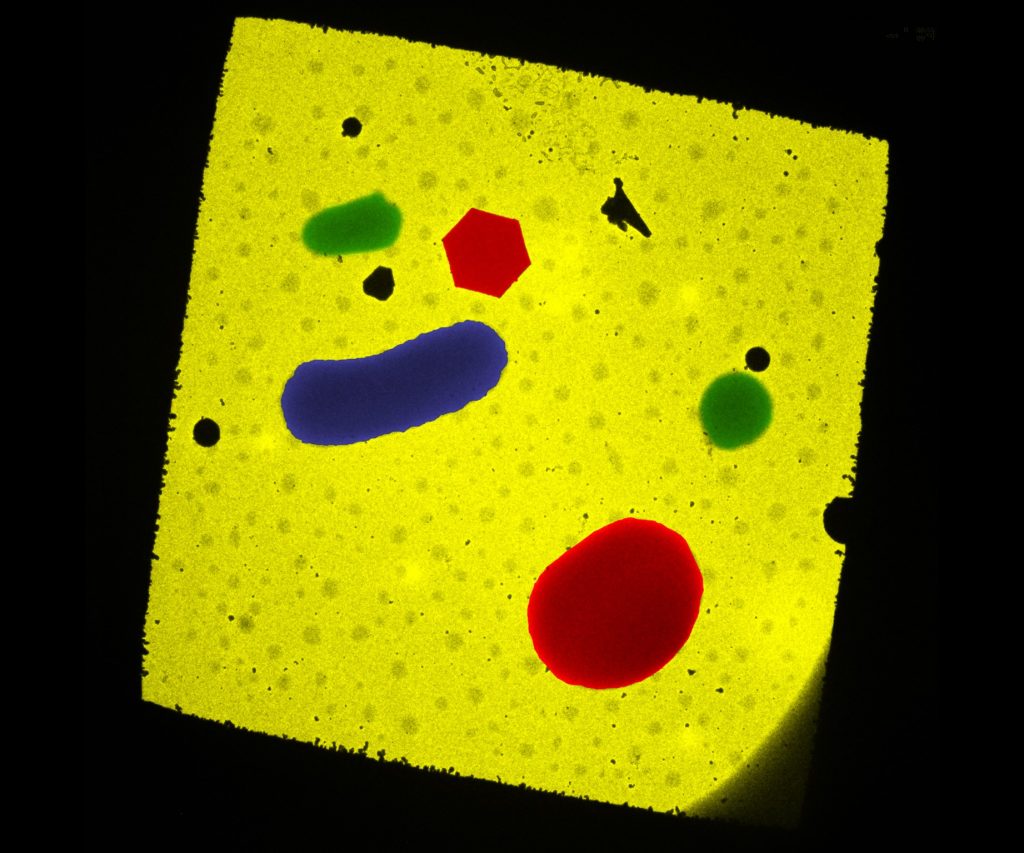

Excellent question. I think I’ve had a few, but none of them came while I was at the microscope. It came while I was watching the images. But a moment that marked me at the microscope, that I do remember, was more artistic rather than scientific. I was doing cryo with a colleague at Institut Curie, and we found something aesthetically extraordinary. We found an artifact due to freezing. We found a hexagon and some precipitated next to it, which made it look like a painting from Joan Miró. This happened on a Saturday and I remember thinking ‘I won’t waste time on an artifact’. But my colleague said ‘It looks like Miró, right?’. So we decided to take a picture. This picture won an award at a microscopy competition. It was no biology, but rather art.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Brazilian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

It’s a great idea to become a microscopist. Perhaps I’d repeat something that was said to me: ‘I love this, it is the best thing I have ever done in my life’. Go for it, don’t give up. I think the most difficult part is not to give up – it’s a difficult career. But there’s still plenty of thigs to take pictures of J The world is your limit! Microscopy has a huge number of worlds to discover: for instance any cell we don’t yet know (just for fungi we are speaking about 1 million species), and give insights into vast applications: biotechnology, food industry, environment, etc. So it’s totally worth it!

Where do you see the future of microscopy heading over the next decade in Brazil, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

An advance where I see potential, is Brazil having participated in the topic of single particle analysis. As far as I know we have two centers, one in Rio de Janeiro and one in São Paulo, the latest with a huge focus on this. Conversely, I feel we are lagging on technology for cryo-processing of samples, eg. high pressure freezing, and freeze substitution. Brazil caught the wave of FIB-SEM and other volume-rendering based techniques, but sample processing didn’t become so popular. Another thing where I feel we are behind as well is image analysis and the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning for this purpose. We also should put more resources for the processing and storage of the vast amount of data that can be generated with all the new technologies.

Finally, Brazil is the largest Latin American country, and one of the largest in the world. Beyond the science, what do you think makes Brazil a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

We have a reputation of being easy-going, very hard-working, creative, and we look for low-cost solutions. We are versatile, and we speak various languages too, and therefore it’s easy for foreigners to communicate here – we will find a way to interact. The weather is great, the country is beautiful, and the research institutes are well equipped and great to work at. We do high quality science, and we are very warm-hearted and welcoming J . For all scientists out there, fell welcome to come to Brazil!

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)