Science and Art – the not so odd couple?

Posted by Sophie Morgani, on 31 July 2020

At a first, superficial glance, you could be forgiven for placing scientists and artists at the opposite ends of the career spectrum. Scientists need to be accurate and methodical. They must generate highly reproducible data while adhering to strict regulations. On the other hand, artists are often stereotyped as disorganized, free spirits, ungoverned by rules, who strive to produce unique, inimitable work. But, despite these differences, science and art have a surprisingly long-standing relationship.

Historically, scientists were artists through necessity. In the absence of the modern technology that now enables us to capture and reproduce microscopic details, they crafted intricate scientific drawings (such as those of Ernst Haeckel) to convey their findings Even today, scientists routinely create illustrations (albeit via digital means) to communicate hypotheses and summarize results. Furthermore the bulk of a scientific paper comprises visual representations of data, which require an artistic eye to assemble effectively. It would likely also come as a surprise to non-scientists that the artwork adorning the covers of scientific journals is commonly produced by scientists themselves. In essence, they act as freelance (although unpaid) artists! Notably, this is not only a one-way relationship and artists have likewise been heavily influenced by science (see Italian Futurism).

Furthermore, if we look closely at the professions of artist and scientist, it becomes apparent that they leverage similar skill sets and character traits. Creativity is essential in art to cultivate novel ways to express oneself and is similarly a central part of the scientific process, required to theorize and hypothesize, to design experiments and new technologies, and to formulate innovative ways to solve problems. Additionally, open-mindedness and avoidance of bias are critical in both careers, to contemplate opposing opinions and explore unexpected avenues. The artistic and scientific processes are rarely linear and demand numerous iterations to reach an acceptable or workable result. As a result, scientists and artists typically possess an immense passion for their field, which sustains them through failures and when projects take decades to reach fruition.

Most significantly, the ultimate goal of both science and art is to enrich and advance how we understand and perceive the world. Scientists and artists push the boundaries of what has been done before and must be capable of conceptualizing phenomena of which they have no prior knowledge. Not only this, but they must then be able to communicate this to others – without which capacity, both fields lose much of their meaning.

SciArt

The substantial overlaps between art and science may explain why scientists frequently pursue artistic endeavours – you can find some of them by following hashtags like #SciArt, #Cellfie, or #FluorescenceFriday. There are many forms of science-related art (a.k.a. “SciArt”) that range from raw scientific data, which can be appreciated in and of itself, to the representation of scientific subjects in forms such as paintings, drawings, needlework, and jewellery. In particular, microscopy-based scientific images are widely recognised for their aesthetic beauty by national and international competitions such as the Wellcome Image Awards and the Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition.

For many people “seeing is believing” and it is easier to grasp a concept if it can be visualized. Therefore, collecting and arranging data in a clear and visually impactful way facilitates the communication of science to lay and specialist audiences. Accordingly, an obvious value of SciArt is that it stimulates interest in and discussion about science far beyond the usual academic circles.

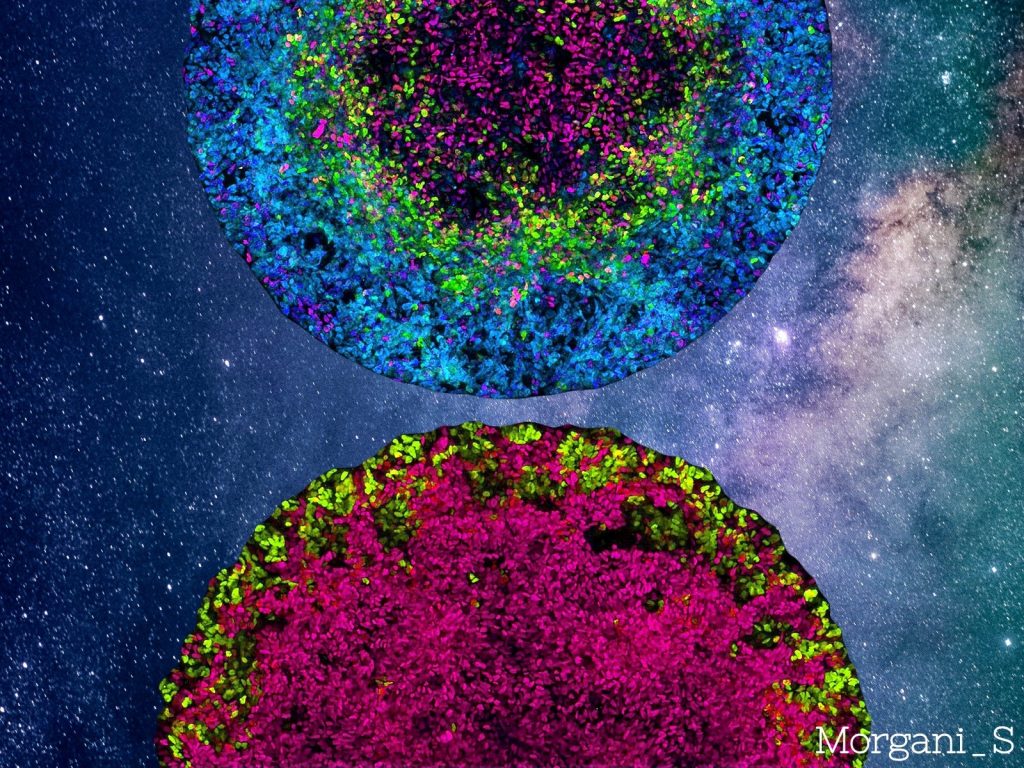

This mouse embryo has been immunostained for transcription factors that mark distinct cell types (Yellow = SOX2, Magenta = NANOG, Cyan = BRACHYURY). The striking expression patterns arising during gastrulation and these vivid colors reminded me of a Bird of Paradise.

My SciArt

The connections between science and art were apparent to me from early on in my research career. My Ph.D. advisor (Josh Brickman) was a former postdoc of Rosa Beddington, who was a renowned developmental biologist and also an artist. Her illustrations feature on the Waddington and (of course) Beddington medals awarded by the British Society of Developmental Biology and decorated the dissection room walls at the former University of Edinburgh Institute for Stem Cell Research. Inspired by this history, I often discussed the notion of science as art and would get extremely excited about beautiful microscopy images. One of my earliest Ph.D. memories is that of being introduced to the inadvertent SciArt of my mentor within the lab, Maurice Canham, “Cows On A Misty Morning” – the result of a failed Southern blot attempt. This highlights how the mind of a scientist can find art even in an imperfect experiment!

I have always thoroughly enjoyed microscopy and spend vast amounts of time attempting to capture the perfect image to accurately represent my results. As a consequence, I have amassed a significant collection of microscopy data that will unfortunately never see the light of day in the form of a scientific publication. Over the past years, I have started to post some of these on Twitter (Morgani_S), to communicate the beauty of early development to a wider audience. More recently, I set up an Instagram account (BIOutiful1) where I share modified biological images, for instance, a section of a mouse oviduct (which resembles the mouth of an exotic, carnivorous creature) superimposed onto a jungle background or migrating mouse stem cells in the form of waves crashing on a beach.

Being a first-generation academic, I am passionate about disseminating and promoting science and STEM careers to people from backgrounds such as my own, that may not otherwise consider this profession. I hope that the juxtaposition of everyday scenes and objects alongside unfamiliar scientific matter will attract and inspire a broader audience to think about and discuss science.

Sophie Morgani

Postdoctoral researcher

Hadjantonakis & Nichols Labs

Sloan Kettering Institute, MSKCC, New York, USA & Wellcome-MRC CSCI, University of Cambridge UK

(10 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

(10 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

Hi Sophi!

I came across your post while researching cell filaments.

I am not an educated scientist but have educated myself in art.

I have created my own color theory, out of perceived necessity,

and thought you might be interested that that color theory turned out to be the same theory that music incorporates, harmony by symmetry in small ratios of waves.

My interest in biology came about by the fact that if color and music use the same small ratios to produce harmony, then cells must use the same basic harmonies to produce, all of the different senses.

Take cell division. The cell has centrioles that use different microtubules to search out the appropriate centromeres. They have to have an attraction to specific ones because they attach both front and back, using mother and daughter. The chromosomes would tangled other wise. The chromosomes themselves have to use different types of scales sense they make different cell types, using different proteins and protein splicings. They all use different notes and chords, or their equivalents, to communicate in different harmonies. At least, that’s the assumption I go by.

So color harmony got me interest in music harmony, and both got me interested in biology. I wanted to see if I could find out how cells create color and music harmony in the brain.

All three subjects are beautiful and inspiring.

I was thinking earlier today that biology is so unfathomable, that it is even beyond possible. The quantum would, however, which plant cells use, is that way too! Maybe, it is used in all cells and is the reason for the balance and harmony found their. If so, the simple harmonies of wave types may be the key to unlocking the confounding complexities in biology.

So, to a fellow artist, thanks for your thoughts!

Sincerely,

Mike

Dear Sophie Morgani,

I read your article by happenstance when my dad suggested looking into the journal. I love how you mirror the realm or creativity and contrast to bring out the intricacies in the cells. I wonder if you have any current projects or areas of art you are working on? Do you have any pieces of art with the Covid-19 viral strand?

Hi Carrigan,

I’m happy that you enjoyed the article and thanks for getting in touch. I don’t have any work on Covid-19 but I am regularly making new science-related art (currently it is mostly related to deveopmental biology) that you can find on @BIOutiful1 on Instagram. Most recently, I experimented with making Mandala-esque patterns with stem cell images:

https://www.instagram.com/p/CF1tLhfj7mO/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

I hope you like it!

Hi Mike,

Thank you for your response and for your thoughts! It’s a really intriguing comparison between music, art and biology. A lot to think about, but definitely not simple to comprehend. Your comment and this connection reminded me of a Radiolabs podcast that I had listened to a while ago. Perhaps you will find it interesting:

https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/radiolab/articles/unraveling-bolero