An interview with Lia Medeiros

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 5 April 2022

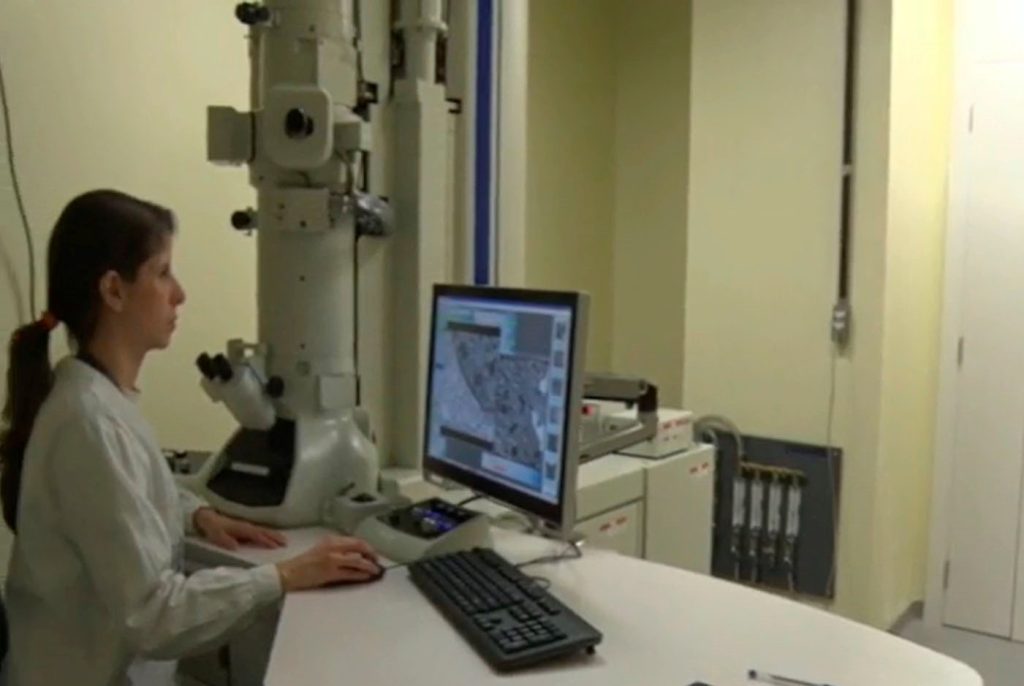

MiniBio: Lia Medeiros is an associate staff scientist at Carlos Chagas Institute, Fiocruz (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Brazil), and is head of the Electron Microscopy Facility at the same institution. She obtained her Ph.D. from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Her Ph.D. research involved the ultrastructural characterization of the interactions between Plasmodium parasites and the host cell at the 3D level. She had postdoctoral internships at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), at the Carlos Chagas Institute/Fiocruz-PR (Brazil), at the University of Georgia (USA), where she worked with the CRISPR technique for gene knockout in Trypanosoma cruzi, and at Molecular Biology Institute from Paraná (Brazil). Currently, she develops research on the molecular and cellular biology of parasitic protozoa such as T. cruzi and Leishmania spp. and their interaction with the host cell. She has experience in the areas of Biochemistry, Cellular and Molecular Biology of parasitic protozoa, with emphasis on ultrastructural morphological analysis by electron microscopy.

Brazil has a long-standing history of contributions to science both, in Latin America and world-wide. It is the land of scientists as renowned as Carlos Chagas and Oswaldo Cruz. It is also a country of fascinating biodiversity, attractive the whole world around. Before becoming a scientist, were you aware of this heritage? What inspired you to become a scientist?

I didn’t really have an awareness of these huge Brazilian discoverers at a young age. I barely understood the concept of scientist. I have the impression that I reached the road of science by a mixture of curiosity and serendipity. I come from a family of humble origins, with limited resources. While we didn’t struggle with basic needs, we didn’t have an excess of resources. Me and my brother were the first to reach University – we are first generation scientists. When both of us were accepted into the Federal University for an undergraduate degree, this on its own was a huge achievement in the family. But I didn’t have anyone who helped me figure out the road of University or science, to choose my degree. I chose my courses on my own when I was 18 years old.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy and infectious diseases. What inspired you to choose this career path?

At some point of my early career, I needed to isolate organelles- acidocalcisomes. The only person who knew how to isolate them was the person who eventually became my PhD supervisor, Dr. Kildare Miranda. He gave me some protocols and at some point we went on to observe the isolated organelles in the microscope, and I was fascinated by microscopy. This was the beginning of my involvement in microscopy.

Brazil has renowned and historical institutions dedicated to research (and microscopy). Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your career path and what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Brazil, from your education years?

I was always attracted by biological sciences, so for a long time I thought I’d study medicine, then I thought about biology. When I started studying I actually did the undergraduate degree in Nutrition. Due to a mixture of serendipity and luck, I joined a University where research is a major component. During my first year, I saw other students in labs, and this attracted me very strongly. All our teachers at the time encouraged us to do an ‘Iniciacao Cientifica’- a major component in Brazil which allows young students to join research labs for extended periods of time, where they have independent projects. It wasn’t common for students of Nutrition to do this, but some professors really motivated us to do research. I didn’t really do a rational choice on the research line at the beginning, but rather joined the lab that accepted me. Interestingly before I graduated, I felt ever more as a researcher and no longer so much as a Nutritionist. I ended up never working as a Nutritionist. I did 3 years of ‘Iniciacao cientifica’ and 2 years of MSc.

Eventually, I made up my mind about becoming a scientist. I strategically re-directed my research path and really chose a line of research when I chose my PhD. I had an excellent relationship with my BSc and MSc supervisor, – my supervisor and his wife were ‘academic parents’ to everyone in the lab, and so moving away was a difficult decision. It is difficult to leave one’s comfort zone.

For my PhD, I joined the group of Dr. Kildare Miranda. I started doing research in Plasmodium first, and this switch was a difficult step. I wasn’t very experienced and felt very lost in the lab. But I believe forcing oneself to leave the comfort zone makes you stronger. This decision allowed me to really gain great expertise in Plasmodium and microscopy techniques. When I defended my PhD, I continued as a postdoc in the same lab, and I felt that my first postdoc was really an extension of my PhD. At this point I met my husband, who lived in a different city, in Curitiba, while I was in Rio de Janeiro. In order to be together, I moved to Curitiba. I feel moving away from the PhD lab is important because staying in the same lab where you were a student can result in you not being taken so seriously – you are seen as a trainee, rather than an experienced scientist. I wanted to ‘grow up’. When I moved to Curitiba, I felt really recognized and respected as a professional. Eventually I did a one year postdoc in the USA in the lab of Prof. Rick Tarleton’s lab at the University of Georgia. I thought this was necessary for my scientific career. I thought this experience abroad would make me grow professionally and personally. After I came back from his lab, I applied for the position I currently hold as a researcher and a facility manager of the microscopy platform in Curitiba.

When I had the opportunity to work abroad, I noticed that the Brazilian education system is very strong. We get to have our own projects, and do science, very early on in our careers. I think this is invaluable. Now as a supervisor, I like being involved directly in teaching and training of young scientists.

You are currently the leader of the microscopy platform at Fiocruz. Can you tell us a bit about your job?

I am really trying to find a balance, to avoid becoming an absolute bureaucrat. I want to still be able to sit at the microscope and do science. The chance to lead the platform came very soon in my career. The former leader of the platform retired and I took his place two years later, but I also became a group leader around this time. I am currently focusing on trying to educate the next generation of microscopists. I really have as a priority to give access to young scientists to all the microscopes, so that they become capable and competent microscopists.

Throughout your career you have belonged to various world-renowned centres of microscopy? Can you tell us a bit about your path, and how did this shape you as a microscopist?

Being in Prof. Wanderley de Sousa’s lab was vital for my career. This lab was a dynasty of microscopists with figures like Marcia Attias, Kildare Miranda, Narcisa Cunha-e-Silva, etc. In this environment you learn by osmosis. It’s impossible to work at the Laboratory of Cellular Ultrastructure Hertha Meyer, and not come out of there being an experienced microscopist. You spend time and learn from the very best: you are at the bench with the very best, you discuss papers with them, you get classes from all these experts. This made all the difference for my career. It’s not only about the theoretical side, but the huge practical expertise. It’s the perfect environment. There are of course other centres in the country that also are excellent, but it is not uncommon that these various centres are many times led by people who studied under Prof. Wanderley de Sousa. I feel very proud of being of this ‘family line’.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Brazil?

I think we should strengthen science in Latin America. I feel the colonial history still bears a huge weight on our societies. Collaborations tends to be sought in Europe, partly because of this history and partly because resources are limited in our region. Just as Brazilian science is struggling with funding, the same is true for our neighbors. So we end up looking for collaborations in places with better infrastructure than our own. But I think the future is really to build a strong network in Latin America. I think we have excellent scientists in the region. Moreover, we have extraordinary biodiversity in our own countries where a lot of research can be done in-house. I think the potential is there, and it is extraordinary. Perhaps another venue to explore is private funding options. Some of the ones supporting work in the region are the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, etc. And these have a huge weight – I think science will be key for many social issues to address in the future, including social inequality, public health, climate change, etc.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Brazilian researcher, working abroad?

I think when I worked abroad I realized the difficulties of doing science in Brazil. When I was in the USA I noticed that obtaining reagents was much more efficient, and that science was much better funded than it is in Brazil. When I worked in the USA, there were many foreigners in the lab – it was very diverse so it wasn’t very difficult for me to adapt. My experience in the USA was quite peculiar. I think the main challenge of going abroad was that my husband couldn’t join me. It was difficult to be separated during this time. Moreover, there are cultural differences between the USA and Brazil which can be challenging. Nonetheless, as a ‘carioca’ (person native of Rio de Janeiro) I find it easy to communicate with others, so I found it easy to interact with others.

Who are your scientific role models (both Brazilian and foreign)?

My main role models are my supervisors. They were essential for my career. This includes my supervisor in the BSc/MSc, and then later in the PhD, of course Prof. Wanderley de Sousa, and Prof. Kildare Miranda. And outside of Brazil, my supervisor in the postdoc I did in the USA, Prof. Rick Tarleton was also a role model. He is not a microscopist but he is one of the brightest people I’ve met in my life. He has strong ties to Brazil, and I felt he understood the ‘universe’ where I was coming from as well. Of people I don’t really know, of course Carlos Chagas is most amazing scientist of all: in the early 1900s, he discovered the disease, the parasite, and the life cycle. I see him as a visionary, ahead of his time, and super intelligent.

Brazil has one of the best equality in terms of gender I have encountered as a researcher, with women heavily involved in research, at various leadership levels. Was this something that influenced you? How?

I think it makes a huge difference for us to have this mirror: women in positions of leadership. Even though Brazil has a better gender balance than other countries, and even though we have seen improvements in gender balance in recent years, the difference between genders is still significant. People in leadership positions are still mostly men. We come from a patriarchal society. Moreover there’s the topic of maternity: nowadays there are attempts to help women in science who are also mothers, for instance with specific funding opportunities that take maternity into account. I feel this impact of parenthood should be equal for men and women, but in reality this equality doesn’t exist, and women still take the bigger impact of parenthood.

Still, things are changing: today, the dean of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro is a woman; the president of Fiocruz is also a woman. We should empower young women so that later these women become leaders and reach positions at all levels, equal to men. I think there is still a long way to go. I feel in microscopy though, we don’t face as many inequalities in terms of gender, as women in physics and mathematics do.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

TEM! I think SEM gives fantastic images, but in terms of answering research questions and its versatility, TEM is powerful, fantastic and elegant.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An ‘eureka’ moment for you?

I think the most amazing thing I have seen by microscopy was the 3D view of the complex interactions between Plasmodium and the erythrocyte. Looking at these structures at 2 dimensions can be very hard to interpret. When I started to reconstruct 3D model of infected red blood cells I was absolutely amazed by the beauty and complexity that biological structures can form!

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Brazilian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

I think if you want to be a microscopist, you have to join a lab that ‘breathes and lives’ microscopy, that has vast expertise in microscopy, that has all necessary equipment to do microscopy. That has the best microscopists of the country.

Where do you see the future of microscopy heading over the next decade in Brazil, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think a big strength would be to have hubs around the country, making it a strong network. That each specific hub has the best possible infrastructure, human resources, and expertise. I think it would be best to distribute expertise around the country, rather than focusing all the resources in a specific region as is currently the case for Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

In terms of the toolkit directly, I was told early on in my career, that the future of microscopy was cryo-EM. And I feel the future has arrived!

In terms of politics and funding, perhaps Brazilian science is currently undergoing very dark moments. But I think Brazil has extraordinary human resources. If we can organize and re-distribute our resources, which is something that the Brazilian Society of Microscopy and Microanalysis is trying to do, we could achieve a lot more. Brazil is an enormous country, so I think there is a lot of potential everywhere.

Finally, many Brazilians are receiving training abroad, or within the private industry, which will translate into expertise being brought back to the country.

Finally, Brazil is the largest Latin American country, and one of the largest in the world. Beyond the science, what do you think makes Brazil a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

Brazil is a huge country, with huge biodiversity, many cultures, many types of ecosystems, etc. The heterogeneity among the Brazilians make it a fascinating nation: there is no ‘Brazilian face’ – we have a huge mixture of races. Moreover, people are very welcoming. We are proud of being Brazilian, and we always want to show people our country. Our culture is very welcoming and this is nice for someone coming from abroad.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)