An interview with Lucas Pagura

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 23 August 2022

MiniBio: Lucas Pagura is a postdoctoral fellow at the Immunology and Infectious Diseases department at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He has a long-standing interest in parasitology and microscopy. His current work focuses on understanding the metabolic interface of host-pathogen interactions of the intracellular parasite Trypanosoma cruzi in mammalian host cells. He did his PhD at the Instituto de Biologia Molecular y Celular de Rosario (IBR-CONICET) in Rosario, Argentina, where his main project focused on characterizing the protein TcHRI in T. cruzi using a range of molecular biology tools and imaging methods. During this time, he participated in the prestigious Biology of Parasitism course at MBL in Woods Hole, USA. Prior to his PhD, between 2005 and 2011 he completed his early studies as a BSc in Biotechnology at Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Argentina.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I think it all started since childhood. I was a very curious child, and this continued throughout my life. As a child I used to combine any and all liquids at my disposal to see what would happen when I mixed them or if an insect came into contact with them. I was always interested in ecology and biology. An important turning point for me was also to watch the movie Jurassic Park. To me the concept of DNA was unknown at the time, and the (fantastic) idea that a dinosaur could be brought to life based on this, became something absolutely fascinating. Because of this, I wanted, for a very long time, to become a paleontologist, mixed with some interest in veterinary science, and health. Then in junior high school, we had a subject where we had to speak about new technologies, and at this point I came to learn about genetic engineering and what it meant for plants, food, and animals. Here I started truly understanding what it meant to genetically modify an organism, and what the molecular biology basis for this was. This was sort of a guiding point for me to enter the BSc in Biotechnology in Argentina. The degree had a strong component in Molecular Biology because many professors who founded this career, had this background. Ultimately this formed the basis of my current career and the interests I have pursued as a scientist until now.

You have a career-long involvement in cell biology, parasitology, and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose these paths?

I started my BSc in Biotechnology. In Argentina, most people who study this degree focus on in vitro cultures – mostly relevant to agricultural science, because of its importance for Argentina’s economy. But although I like plants, plant science was never something I was passionate about or something about which I would aim to make a career from. I really was interested in animals and health.

In the last year of my BSc, I did my thesis at the Instituto de Genetica Experimental at Facultad de Medicina at Universidad Nacional de Rosario, studying mammary adenocarcinoma in murine models. This was really my first encounter with scientific research and how to develop a research project. I learned how to plan and develop experiments, how to interpret data in a critical way, and here I had a first encounter with microscopy seeing basic stains in histological sections of rodent tissues. Although it was interesting to me, at this point I wasn’t always completely sure of what I was seeing in the sections. I needed the pathologists’ opinion and advice to interpret the observations.

After that, for my PhD, I entered the area of parasitology a bit by accident, because there were not many vacancies in labs focusing on health. The lab of Julia Cricco was working on T. cruzi metabolism. T. cruzi is the causative agent of Chagas disease, and that topic that was very attractive to me. It was then that I started my career in parasitology. Also, at this point I got much more involved in microscopy, mostly fluorescence microscopy to observe different aspects of T. cruzi. Before I joined her lab, I already knew about the existence of Trypanosoma cruzi, because it’s endemic in Argentina. But I didn’t know much about other equally relevant parasitic diseases in the region. During my PhD, because of opportunities I had to travel and interact with other researchers in Latin America, I became aware of the huge plethora of parasitic diseases present in the region and the huge public health burden they represent. I think only then I understood better the public health challenges we are facing in our region, and the importance of studying these parasites. This interest is still present, and although I have had the chance to continue working on T. cruzi, I think parasitology is an exciting area of research, with many things in common between parasites and how they interact with their hosts. I find it fascinating.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Argentina, from your education years?

In Argentina, a very good thing is that public education is really good. Basic education (primary and secondary school) is really good and it prepares you very well for University. I was lucky to attend a very good technical school, also public, where the syllabus in the last year was very similar to the syllabus of the first year of my BSc degree in University. This meant a very smooth transition, almost without any difficulty. Perhaps some students egressing from other schools might have had slight difficulties particularly in Physics or Chemistry, but I didn’t face this. I think in Argentina once we reach the end of the BSc, the level is really good, but I don’t think at this point we are fully trained scientists. This development occurs during the PhD, where we really learn how to do science. A relative disadvantage in relation to countries like Brazil is that we begin our scientific career when we are a bit older. We do 7 years of primary school, 5 years of secondary school, 5 years of BSc degree (as a minimum, because many people extend this to 6 or 7 years), and right after this one can start a PhD. Only then can we start doing research as a much more independent researcher. So, there are pros and cons: the quality of public education is very good, but one is relatively older: I finished my BSc when I was 26 years old for example. Despite the great quality of the education system, we still face some disadvantages from the lack of resources: during our BSc practicals, most work is done in groups (there are not enough resources for individualized or complex experiments). And throughout our career we really maximize resource utilization. Once I had the opportunity to work abroad (in first world countries) I found it almost painful to see the waste of resources, for instance enzymes, kits, etc. I feel maximizing resource utilization is an ability we acquire in Argentina: we become very resourceful and we learn how to optimize time usage (for instance usage of instruments such as microscopes or spectrometers). For us, for instance, some materials don’t have an expiry date per se: we stop using them when they stop working. We don’t tend to use kits: everything is home-made. A positive aspect of this is that this results in a very good understanding of the scientific basis of the experiments we do. But of course, this is more time consuming and might result in poorer yield. In terms of time, for a career as competitive as science is, time is a valuable asset, and this is not something often considered when evaluating scientific quality and output: I’ll give you an example: if you order a primer in Argentina, it might take up to 1 month until you have them with you. Same is true if you send something for sequencing. In the USA, you could have what you need within a day or two. This affects both, teaching, and scientific development. But we are resourceful, and we find ways to keep going and doing science.

Can you expand more about how your career has progressed in the line of microscopy?

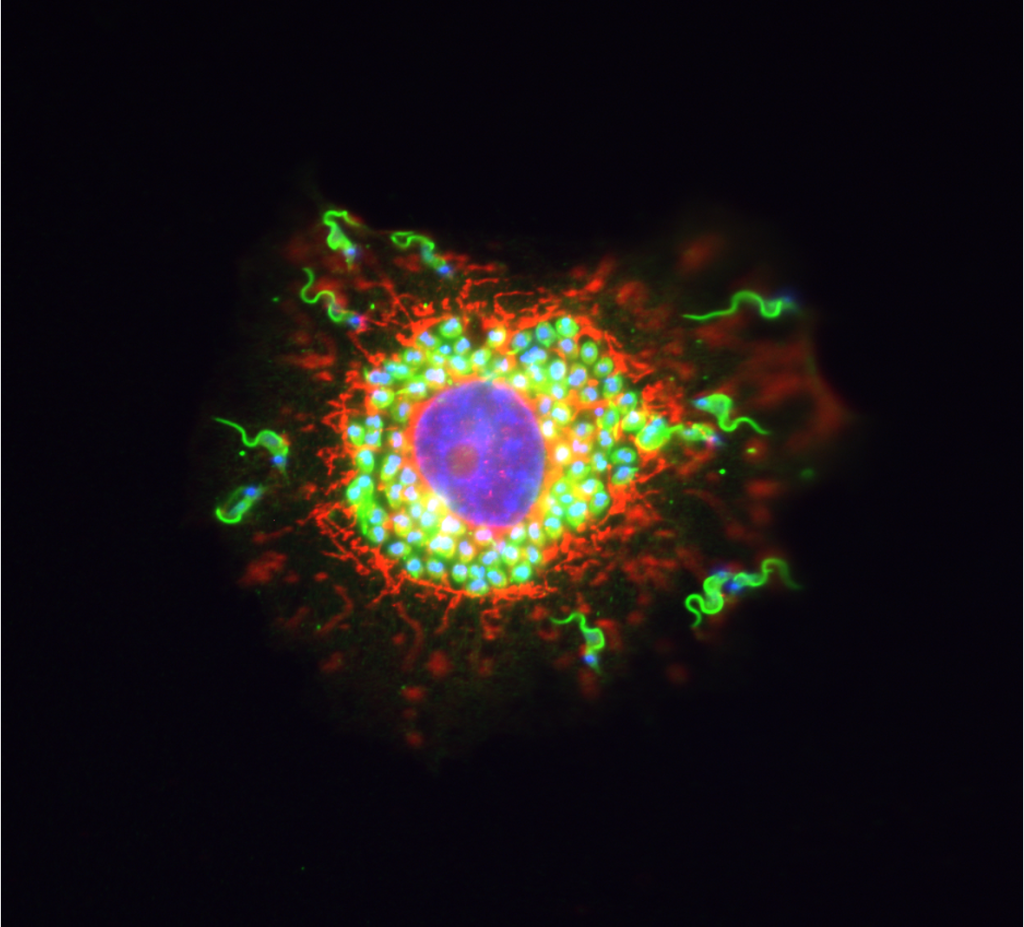

Early on in my career, in terms of imaging I mostly focused on sample preparation, staining and analysis of histological sections using a light microscope. In my PhD I became much more involved in fluorescence microscopy. We generated reporter lines to study protein localization in different cells, using yeast, eukaryotic cells, or even parasites to observe protein localization. We used also fluorescent dyes to study incorporation (or lack thereof) of different components, into the various cell types we were using as models. I always loved microscopy also from an artistic point of view! And the amount of scientific questions one can address with microscopy as a discipline in itself. I often found myself distracted, observing phenomena beyond the question I was trying to address. I would often acquire images out of fascination! During my postdoc, I have also had the chance to do electron microscopy. I was impressed by the quality of the images and the amount of information one can get from these images. But it quickly became clear to me that this is a completely different discipline. It was overwhelming! I admit my experience in EM is limited, and although I enjoyed the experience, I feel much more comfortable working with optical microscopy, and I understand these techniques better –enough to twist-modify protocols and use them to answer my scientific questions. This is not yet true for EM for me. Perhaps in the future I understand this better and so will feel more comfortable using it as an ‘everyday’ tool.

Regarding future applications I am interested in using and learning are super-resolution microscopy and expansion microscopy, to answer questions relevant to my project. It would also help me address some questions that remained pending in my PhD, specifically relevant to protein-protein interaction, or interactions with different compounds and ligands. I think expansion microscopy would be great to answer these questions. Also, during my PhD, I went to Sebastian Brauchi’s lab at the Universidad Austral de Chile, to learn TIRF (total internal reflection) to study agglomerates of the protein I was studying and see if it would form multimers of a certain number of subunits. I found this super interesting, and a very ingenious technique which allowed us to quench individual GFP subunits and follow fluorescence bleaching through time, and see if the protein was forming dimers, tetramers, etc. In his lab, they didn’t depend on commercially available microscopes, but they were able to make their own equipment. They were truly able to adapt the microscopes for each experiment and research question, and I found this amazing.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Argentina?

While I was in Argentina, we had collaborations with groups from Brazil, like Ariel Silber and Marcia Paez, from the University of São Paulo. I also had the chance to collaborate with Sebastian Brauchi in Chile. But I feel collaborations can be improved a lot between labs in Latin America –I don’t think these opportunities for collaborative work are maximized at present. I have had the chance to attend conferences and courses within Latin America (in Colombia and Brazil), where I realized that the scientific quality of the work being done in the region is very high, but as a region we don’t have enough networks joining the countries of the region. My opinion on this is that it is common that Latin American groups tend to look for collaborators abroad (in the Global North such as Europe or the USA), where more resources can be invested in the individual projects, rather than potentiating work and collaborations in the region. There is room for improvement!

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as an Argentinian researcher, working abroad?

I am currently a postdoc at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. I think my biggest challenge remains the language barrier. I never had a formal education in English. At University, from the 4th year onwards, all books and papers are in English, so we end up learning out of necessity. It is very difficult for all those without a formal education in the language. Then the oral capacity comes from watching movies and listening to music. One of the first instances when I realized how hard it was, was when I attended the Biology of Parasitism course at MBL in Woods Hole. But I also noticed that as the weeks went by (the course lasts almost 2 months), I felt much more comfortable with the language. With regards to the scientific level, despite being at Harvard, I never felt at a disadvantage relative to other scientists. I think this is a recognition to Argentinian education, where the knowledge we acquire is very high quality, comparable to important institutions of the USA.

Who are your scientific role models (both Argentinian and foreign)?

I don’t know if I have someone specific as a role model. I think all the PIs I have worked with have played a key role in my scientific and personal development. I have been lucky to have had great mentors since my BSc – all the PIs were not just very capable scientists but also very nice human beings. They have all been very supportive both on a scientific and personal level, for all the decisions I have made. I also had great teachers during my BSc, who allowed us to open our minds and search for solutions to problems, out of the box. It would be unfair to mention specific names.

At the same time, I think we can learn a lot from bad experiences – we can have role models of what we don’t want to be like, and what attitudes we don’t want to replicate. I think I have been able to learn from the qualities and limitations of mentors and professors, for my scientific and personal growth.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Argentina, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I have worked with women PIs all my career, since my BSc, the PhD and now my postdoc. In Argentina, most of my colleagues were women (about 60-65%), during the PhD too (perhaps around 55-60%). But the majority of group leaders and directors of institute or department are men. This is a clear unbalance. This shows a difference, certainly not in capacity, but in opportunities to reach positions of power in Argentina. I think efforts are underway, but there is still a long way to reach equity of opportunities with regards to gender balance. There are various movements in Argentina that are aiming at promoting and reaching gender equity, but this intention still has not fully translated into real achievements. I think this is a shortcoming common to all of Latin America, arising from ‘cultural’ trends that are deleterious to women.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

All types of fluorescence microscopy is what I love, both because of the scientific questions one can address, and the artistic link to science. One area I still have to explore (and would love to) is live imaging of dynamic processes. So far, a lot of the work I have done has focused on static events. But it’s something I’m looking forward to learning and using.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

Using bright field microscopy was to see in an in vivo infection. I was able to see the parasites moving within the cell, and then how the infective forms of T. cruzi parasites caused the cell to rupture, releasing many parasites that then went on to look for new host cells to invade. Seeing the exact moment of host cell rupture and parasite egress was something wonderful to observe.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Argentinian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

You should pursue science if this is what you want to do, and Argentina provides a great environment for scientific growth. I would advice to never stop asking questions to your teachers and other researchers. Also, try to do, with your own hands, as many techniques and experiments as possible – lose the fear of science. Expand your horizons: Try to participate in international conferences and congresses, and get away from the comfort zone of your own city: try to collaborate with researchers within your own institute and outside of it. For this you need a supportive mentor that introduces you to a network and promotes your belonging to it. I think good mentors see that this exposure is beneficial not only for you as an individual but also for the team you belong to. As a microscopist, I would say that it’s important to get hands on experience on the microscopes early on, also to lose the fear to these imposing machines. Perhaps a disadvantage in Argentina is that we don’t have a lot of equipment and many times we depend on a technician or someone with great expertise in microscopy, to take the images for us. We sit next to this colleague and ask them to take the pictures we need, instead of being oneself who handles the microscope and takes the pictures. Ask your colleagues to train you and explain to you the principles of microscopy. Aim at gaining the most knowledge possible at each stage of your career. Try to go above and beyond.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Argentina, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

Science in Argentina depends a lot on public financing, and therefore depends on the State, and this depends on the dominant political party in the country. There are periods of time when science is really undervalued, and others where science is well rewarded and receives a lot of funding. This lack of continuity is damaging and leads to uncertainty. There seem to be two models, both in public policy and public perception, whereby in one case, science is seen as an investment needed for the country’s development, and in the other case, science is seen as a waste of resources that could be better used for different purposes. We always hope that we will see improvements, but it always depends on who is in positions of power in the government. A good thing is that scientists in Argentina are very resilient and persistent: we continue doing science, and re-inventing ourselves, despite the lack of certainty for the future, and the lack of resources. We have managed to survive moments of crisis. I think Argentinian science will continue to grow in the coming decade, at faster or slower pace, as we have been doing in the past. In terms of microscopy, I think there is better investment now on infrastructure and human resources. A great improvement has been the generation of the Sistema Nacional de Microscopía, which is a network that connects all big equipment in the country. This has facilitated access to use them: all equipment belonging to a national institution is available to any Argentinian scientist who requires it, and one can book these microscopes, regardless of the institute where such equipment is located. This is a great network for collaboration that has been further promoting national science.

Personally, I hope to be able to return to Argentina. My initial hope was to go abroad for two years and then return to Argentina. So far, I have been overseas for 4 years (including the years of COVID-19 pandemic), but my wish is still to return to do science in Argentina. I don’t have a strong or specific wish to become a group leader: perhaps a more honest answer from my part is that I see myself doing science, regardless of whether this is leading my own group or contributing to the general development of science, answering scientific questions, which is a big driver for me. I truly believe one can do this without the need of being big and famous.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Argentina a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

If a scientist asks me this, the answer will be that the scientific level is really good, and you will find very bright scientists you can work with. I think people will be very helpful and excellent collaborators. People in general are very warm. The country is very versatile in many ways, starting from the population itself, nature, biodiversity, etc. There is enormous cultural wealth, in music, cinema, theater. I think there is something for all tastes 🙂 you will feel at home regardless of your interests and tastes because there is something for everyone. The food is fantastic as well – reflecting the versatility and diversity of the Argentinian population. And let’s not forget mate: from East to West, North to South, mate is omnipresent in Argentinian culture 🙂

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)