An interview with Horacio Legal

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 31 January 2023

MiniBio: Prof. Horacio Legal is a group leader in the area of Image Analysis at Universidad Nacional de Asuncion in Paraguay. He is also the co-founder of the postgraduate program in the area of Computer Science at this university. Horacio completed his Bachelors degree in Electrical Engineering at the Universidade Federal do Paraná, in Brazil in 1988. While working at ITAIPU Binacional, he also completed a Masters degree in Electrical Engineering and Industrial Information Technology at the Centro Federal de Educação Tecnológica do Paraná, also in Brazil. He continued to work in industry, and in the year 2000 started his PhD at Pontificia Universidade Católica do Paraná, in Brazil. It was during his work at ITAIPU and his Masters degree that he gained great interest and expertise in the field of image analysis. In 2004 he returned to Paraguay and in 2007 participated in the creation of the first PhD program in Information Technology (later, Computer Science). He collaborates extensively in the field of image analysis, in versatile projects and with researchers of multiple areas including agricultural sciences, molecular biology, chemistry, and materials sciences among others.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

When I was a child, I never thought about becoming a scientist. I wanted to be an Electrical Engineer. That was my dream since I was about 8 or 9, and that’s really what I ended up studying and what I graduated as. I went to Brazil to study my bachelors and I lived there for over 20 years. Upon graduating I started working for ITAIPU Binacional, a binational enterprise focusing on renewable energy, with Paraguayan-Brazilian participation. It was there where I actually started working in the field of image analysis. The idea of becoming a scientist only arose 20 years after my graduation, when I came back to Paraguay and I was invited to join the University (Universidad de Asunción) and create the first postgraduate degree in the field of Technology. So really, my ‘scientific career’ per se just began about 17 years ago. Regarding my interest in engineering, when I was a child I had contact with the first personal computers like the Comodore computer. But rather than my interest being on putting together the machine itself, my interest was rather to learn about user-computer interaction. It’s been a while: during my undergraduate degree, when we studied Introduction to Computer Science, we were still using perforated cards. I stopped telling this story in my lectures because my students now look at me like I’m from a completely different era.

You have a career-long involvement in image analysis. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

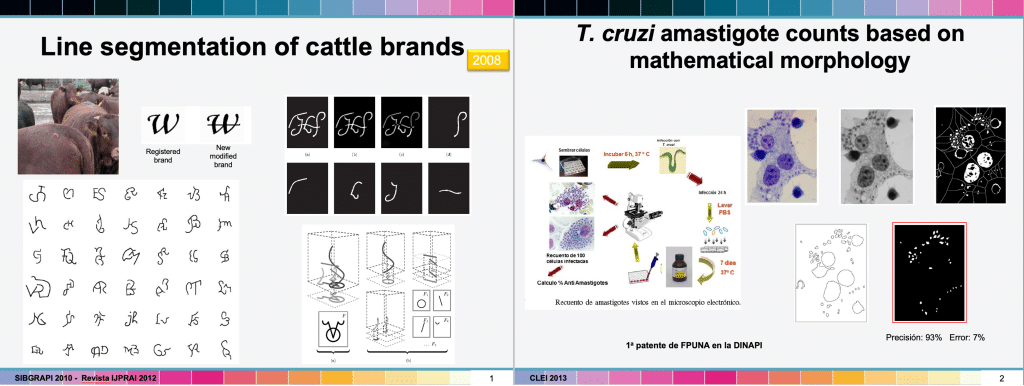

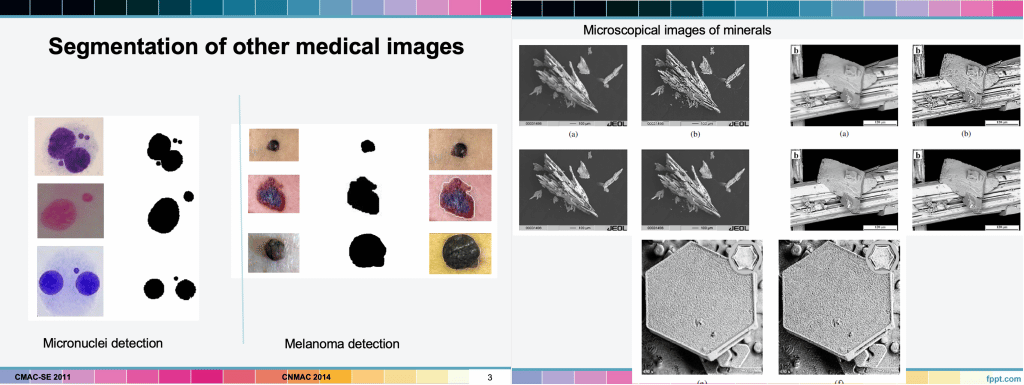

It happened during my Masters degree in Electrical Engineering and Industrial Information Technology at the Centro Federal de Educação Tecnológica do Paraná, Brazil. I was working at ITAIPU and doing my masters simultaneously. And it was exactly around this time when I started working on image analysis. During the masters degree, we had to choose a sub-specialty, and I chose industrial automation. Actually it’s a long story: because I was doing the masters degree and working simultaneously, for my first year, I was given a chance at ITAIPU to attend all lectures of the masters degree without restrictions. But the following year – the year of the thesis, I had to organize my schedule to fit both things. Being in Industrial Automation, many subjects had labs which required in-person attendance – a requirement which clashed with my job at ITAIPU. So I had to think of a project which I could do remotely so I could complete the lab practicals by myself. And the opportunity arose in the field of Image Analysis, which I could work on from my own computer – wherever I was. That’s how I got introduced to this area. Moreover, my work at ITAIPU already involved image analysis and archival. So, one thing led to another, and this is how I got into the field. I did my PhD much later – I worked at ITAIPU from 1989 to 1998 and during this time my former masters supervisor invited me to do a PhD in the same topic I had done my masters thesis. So, there was a 10 year gap between these two career stages. It was an interesting experience to have PhD colleagues who were 10 years younger than me. This is relatively uncommon. I did my PhD at the Pontificia Universidade Católica do Paraná, in Brazil. I completed my thesis in 2004. Nowadays, here in Paraguay it’s very difficult to become hyper-specialized in one type of image, so the Image Processing group I lead specialized in all types of images. For example, the first masters thesis of one of my students was on Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes – there, we worked in collaboration with biologists and chemists. Before working with my collaborators, I thought that the analysis of blood from field samples was automated, but it turns out it was done manually. They thought automation was not possible. So, in this collaboration we designed software which does exactly that: it’s equivalent to what the hemogram does. We designed the software which we also patented here in Paraguay. We’ve also worked with collaborators in the area of molecular biology, in the area RFLP (restriction fragment length polymorphisms) based on PCR. Basically, they would get the images of genes and we would quantify those images. In other types of studies, we did classification of macroscopic images, for example different breeds of cattle, to see how different or similar the various breeds were. We also collaborated with colleagues from the area of materials science, who do microscopic work, and for whom we do image analysis of hydroxyapatite. Altogether, we collaborate with any group who deals with images, and who require assistance in image processing and image analysis. We don’t really choose macro- or micro-. Microscopy is only one type of image that I deal with.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Paraguay, from your education years?

I completed my early education in Paraguay, and from my undergraduate onwards in Brazil. I would say most of my experience in this respect came much later: I came back to Paraguay in 2004, and in 2007 I was invited to participate in the creation of the first masters and PhD programs in Computer Science. This was at Universidad Nacional de Asunción. This was a struggle because around that time (in 2007) the idea of Research being a branch of University activities, was still not well established. Until 2010, a university’s main task was to train undergraduate students. There were a few specializations but not per se postgraduate degrees. So, we had to build everything from scratch. In the area of Image Analysis, I had to start everything on my own – it was myself and the walls. I had to ask for support from my foreign colleagues – they came to Paraguay to give seminars, co-supervise theses, and slowly we started building the department. Today we have a more stable group, with 2 or 3 PhDs who finished their degrees and joined the department, and are now supervising master students of their own. It took a while to get the ball rolling! In terms of governmental organisms, our Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología – CONACYT (which shares the name with Mexico’s main scientific organism) started working in 2009 – despite being founded 12 years earlier. Within CONACYT we have the PRONII system (Programa Nacional de Incentivo a los Investigadores) which categorizes researchers in different levels. CONACYT helps in the handling of research projects and organizing funding – all activities which previously did not exist. For me, it’s impressive to have seen this progress. There was nothing before, and now we have made major steps. I see sometimes younger students take it for granted and feel like this academic system has always been there, but it’s something relatively recent.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as an engineer and image processing expert at Universidad Nacional de Asuncion?

When I joined the University, we opened the masters and PhD degrees and since 2010 I am the coordinator of these programs in the field of Computer Science. Since then, I have three main activities: the coordination of the programs, my own research, and teaching. My day-to-day usually starts with management issues: enrollment, registration, etc of students. Then later in the day I meet with my group, and this involves direct supervision, revising the literature with them, discussing their projects, etc. Then, depending on the day, I teach. It’s always a mixture of activities.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Paraguay?

I did all my professional studies in Brazil. After I came back to Paraguay, collaborations with foreign colleagues were pivotal – and fruitful: these collaborations were necessary to reach a critical mass to start the postgraduate programs. We had very few PhDs in the country, in the area of technology around that time, who would be able to contribute to teaching in the postgraduate programs. So, we had a lot of support from Brazilian, Argentinian, and Mexican colleagues. From Mexico they came mostly from CICESE (Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada), in Baja California, Mexico. Outside of Latin America, we also had strong collaborations with Spain. It took us about 5 years to reach a critical mass. Today we no longer depend on external collaborations to maintain the postgraduate programs. What we have are colleagues abroad who act as co-supervisors, and this fosters international collaborations and student exchange, for example 6-month “sandwich” periods for Paraguayan students to gain experience in labs abroad. This has been great for collaboration and is also a solution when we cannot cover specific technological needs within Paraguay. For example, when we are lacking a specific type of equipment for the development of a thesis. Then the student can go abroad and do those experiments in the co-supervisor’s lab who has the necessary resources. Then the student comes back and does the remaining analysis and writeup.

Who are your scientific role models (both Paraguayan and foreign)?

There are several. Initially, when I joined my field, two people became role models: Jean Serra y Georges Matheron – they were two French scientists who invented mathematical morphology. Image processing is all based in mathematical morphology. They constructed all the theoretical basis in black and white and shades of gray. They literally created all that theory from scratch. Nowadays the theory for colour is not yet fully solved. Whoever manages to create a solid theory for mathematical morphology in colour will be the next genius in this specific subject. So, they both are my role models in that they started this field altogether. Here in Paraguay, my role model is Dr. Benjamín Barán – he is the reference in the country who established postgraduate training in the field of technology. We have collaborated a lot in this task.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Paraguay, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

From the moment that CONACYT became really active for scientists, a lot of effort has been put in creating equality within research and teaching. But there is still a tough reality: if we have a look at all the numbers of students graduating from masters and doctoral programs we see that masters degree graduates are 20% women and 80% men. In PhDs, after 10 years since our doctoral programs creation, only last year the first woman PhD graduated. So, there is still a huge problem in terms of equity. I think this is not specific to the field, but rather we have inherited cultural beliefs that exist in Paraguay. Still at a CONACYT level, and at an institutional level, we are putting great efforts into reaching gender equality. We are working on it, but haven’t yet reached the goals we are aiming for. I should point out though, that my experience and what I mentioned before, concerns the area of technology. But there are other areas which have reached a better balance – that is the case of Chemistry and Biology. So it’s dependent on the field. What I mentioned about Computer Science does not apply to all scientific fields in Paraguay.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Paraguay?

I think the biggest challenge of working abroad is to have to constantly demonstrate that you are as capable as those from the country you’re visiting. You have to work twice as hard, simply to prove that point. This is at the beginning. Once people know you and you have gained people’s trust, you can put the same efforts as any local scientist. But the initial effort is huge.

What is your favourite type of image for analysis and why?

What I like most about image analysis is having a research question that we need to solve. For us, images are data: a bunch of bits and pixels. For the collaborator bringing the research question, there is a problem to solve, and a question to answer. They might bring you a microscopic image of hydroxyapatite or an amastigote, or a breed of cattle, or digital printouts for human recognition and so on. For the end user, these are all different worlds, but to us it’s a bunch of imaging data. We ask the user what they want to answer. For me, finding in the images, the data that will be useful to the end-user is my favourite thing. I am happy to help my colleagues overcome any challenges they have in the realm of image analysis. If my input makes a difference to their work, this makes me happy.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy or the most extraordinary you have analysed as an image analyst? An eureka moment for you?

There’s no single eureka moment. I can tell you several stories though. Having observed a T. cruzi amastigote, for example, was fascinating for someone like me, coming from the area of electrical engineering. And then it was fascinating also to help a researcher automate a process such as image classification. It was a moment of great happiness for me. Another time of great joy was when we obtained the first microscope that can acquire images with nanoscopic resolution, in the department of Materials Science. It’s different to read in a book that you can reach this level of resolution, and a different thing to witness it. These machines are super-expensive and we only managed to get them with the support of CONACYT. We collaborate with our colleagues of Materials Science, and have published together several times.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Paraguayan scientist? and especially those specializing as image analysts?

I would say you really have to have a great desire to pursue this career. Ask yourself 3 or 4 times if this is really what you want because it’s an extremely demanding career. Perhaps in other careers you can try it out for a few years and then decide whether or not to carry on with it. In the area of science, you need to invest a few years just to start seeing some results. You need to do various degrees, various internships and only much later you will define whether the scientific career is for you. I imagine someone who invests all that effort, and after 12 years of studies, dedication, and sleepless nights realizes that science is not for them, will suffer a rather traumatic experience. So really think about your future- you will only find rewards after a very long way (if you find them at all).

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Paraguay, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think science in Paraguay is moving forward. We started working on, and investing in scientific development rather late – taking as reference points our neighbours Brazil and Argentina who started 50 years earlier or more. So we are at a disadvantage in this respect. I try to define objective measurable goals: our students need to publish a lot in order to graduate. Despite our country being so young in terms scientific development, we have a good rate of publications. For example, at the CLEI 2022 (Conferencia Latinoamericana de Informatica), our students received awards for the third best doctoral thesis and the second best masters thesis. So, at a regional standard, despite the country’s late entry to the race, we are reaching these positions of recognition. We have students who are now doing their PhDs abroad, or those who are succeeding in industry positions in international companies. These might seem like small steps, but it’s all indicative that things are going well.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Paraguay a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

I recently read some opinions from foreign visitors which coincide with my own view. Paraguay is a landlocked country that is difficult to reach and because of this, many aspects that are perhaps eroded in other countries, are well preserved here – this ranges from environment and biodiversity, to local customs and traditions. If you want to see how things were done in the past in some area (for example agriculture) you should come to Paraguay. We have some areas that are pretty much inaccessible – without highways or roads. You need to do some intense trekking to be able to reach them. This is appealing to many tourists. In terms of gastronomy, our major difference say, with Mexico’s food, is the spice. But other than the spice, our food is similar to food in the rest of Latin America – it’s based on corn, beans, rice, wheat. With one small difference: the naming convention! Even compared to food found in the Andes, the names are very different. In terms of landscapes, actually lots of people come to Paraguay when they visit the Iguazu falls which are at the triple border between Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina. So many tourists visit the falls, and then cross to Paraguay, perhaps to Ciudad del Este – the closest Paraguayan city to the Iguazú falls.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)