An interview with Noemi Tirado

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 28 February 2023

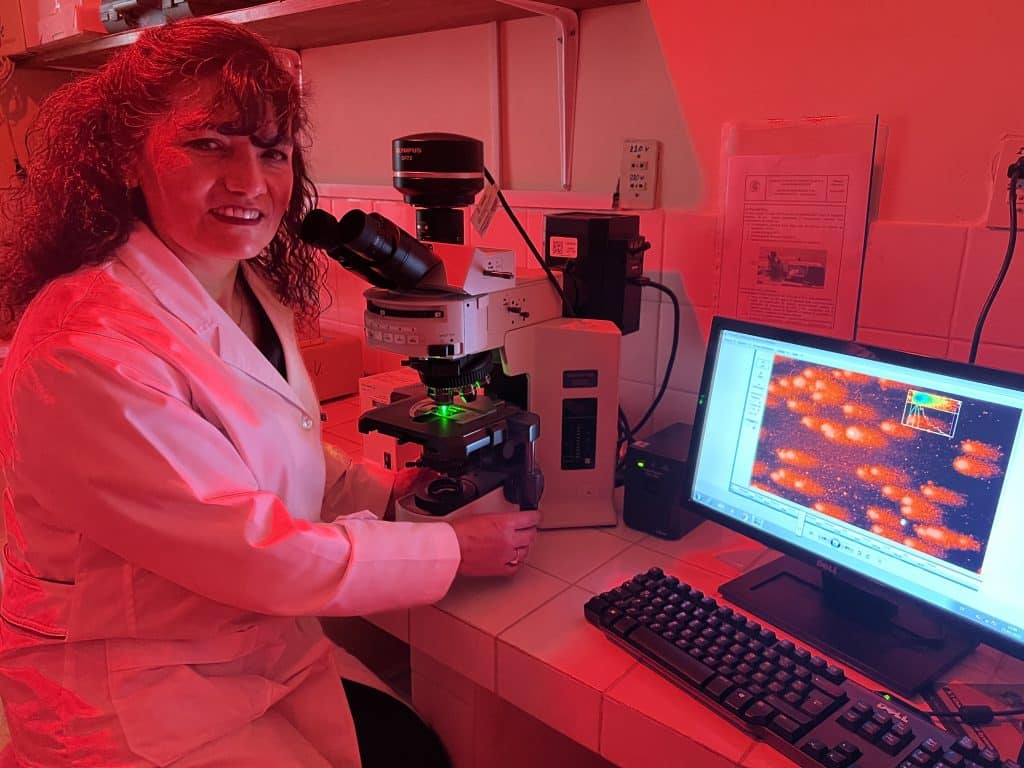

MiniBio: Prof. Noemi Tirado is a group leader and head of the Genetic Toxicology Unit at Universidad Mayor de San Andres in La Paz, Bolivia. She studied her graduate and postgraduate career in Bolivia. Her work is multidisciplinary, including molecular and cell biology in combination with microscopy, as well as clinical research and public health studying the effects of exposure to environmental pollutants such as pesticides and metals such as arsenic. She is a world-renowned expert on this topic, as well as one of the few scientists focusing on this topic in Bolivia. Noemi is also the president of the Latin American Association of Mutagenesis, Carcinogenesis and Environmental teratogenesis (ALAMCTA), Member of the executive committee of the International Association of Environment Mutagenesis and Genomics Societies (IAEMGS) as well as a full member of the Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD). She participates in several international collaborations, including various Latin American countries.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I think what most interested me was to observe the nature around me, like flowers and their structure and what was in them. I liked the micro-world, as well as chemistry. I think this was the case since I was very small. I would sometimes be in the garden, on the grass, and I would see love to see the colors around me, in the sky and in nature alike. I think this was the beginning of everything!

You have a career-long involvement in biochemistry, genetic toxicology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

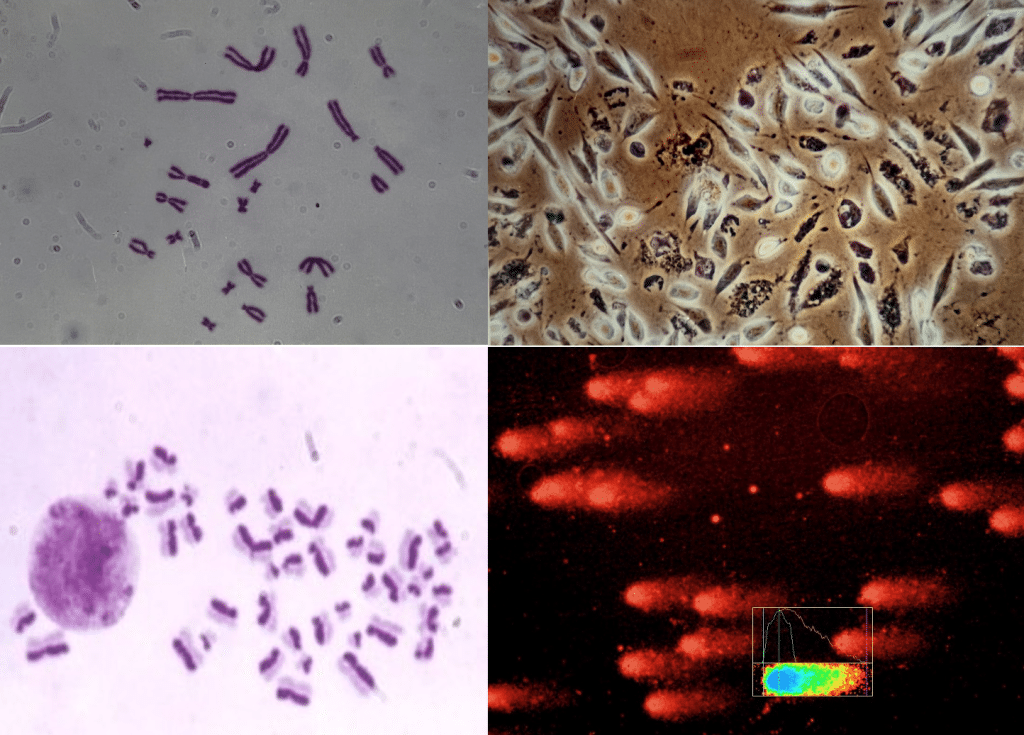

Once I entered University, I joined the degree of Biochemistry and Pharmacy. Already at this early stage, I found microscopy very interesting. Once I had to do my BSc thesis, there were several options. I was working on plant micro-propagation, but I had a chance to work with a new professor. He was a Spanish priest; Dr. Luis Miguel Romero and he was opening up the area of Genetic Toxicology in the Institute of Genetics at the University. Upon choosing where to do my thesis, I spoke with him, and he told me what he had done during his own thesis, and what the main techniques I would use would be. I found it fascinating so I switched topics, and joined his lab. That’s when I started using microscopy, to see cells and chromosome damage. Dr. Romero had a PhD in Medicine, but he was also a missionary. In Bolivia, I was his first student, and I implemented several techniques at the institute. I later had the chance to do short courses abroad, including in various Latin American countries. I was invited to implement those techniques in Ecuador, where Dr. Romero also went to establish this area. I then did my Masters degree in the area of Biological and Biomedical Sciences in Bolivia, but I received a scholarship from IRD (Research Institute for Development) in France, and during this time I also had the chance to attend Hollander training events. I’m currently doing my PhD. I had several opportunities to go abroad, but it was always a bit complicated- I had my job at my current university. Originally, I was going to go to Mexico – I had the funds for the research but not for subsistence, so I couldn’t go. Then I had the chance to go to Brazil. But in the end, I’m doing it in Bolivia. About microscopy, as I mentioned, I started using it in the context of genotoxicity and effect biomarkers where I see damage to cells- specifically, lymphocytes and earlier on, CHO-K1 cells. I would look at micronuclei which are chromosome fragments or full chromosomes that are left over when the cell divides. This is evaluated in 1000-1500 cells per sample. I also looked at exchanges between sister chromatids. I then started doing fluorescence microscopy with staining such as ethidium bromide which allows you to see damaged cells with a technique called the comet assay (single cell gel electrophoresis): if the cell is damaged, you see a comet-like pattern. When I was doing my undergraduate degree, one would still take photographs and would later reveal them – photography is on itself another exciting discipline. Now of course one uses cameras integrated to the microscopes.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Bolivia, from your education years?

When I was young and in the school where I studied, we didn’t have well equipped labs where one could do fancy experiments. I think now there are better facilities and better opportunities than before. At University, in the courses of Microbiology, Parasitology and Biology, we used various microscopy tools indeed. I think it was a good education – very supportive in allowing us to use several tools.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a principal investigator and head of the Genetic Toxicology Unit at Universidad Mayor de San Andres?

I’m now in charge of the Genetic Toxicology Unit, precisely the one where I did my BSc thesis. I supervise several students, both undergraduate and postgraduate, as well as research assistants. Now I’m more focused on acquiring funding to do the research projects. Currently I work on monitoring populations exposed to environmental pollutants, such as people exposed to pesticides – farmers mainly, and people who live and work around lake Poopó and Chipaya, who are exposed to metals in the water, such as arsenic. I also still do several techniques in the lab, including both cell and molecular techniques to study genetic polymorphisms related to xenobiotics, genes related to arsenic exposure and lately I’m doing inter-disciplinary projects, which also helps for diversifying funding options. One project I’m working on is resilience mechanisms and the effects of climate change. This involves areas such as agriculture, chemistry, ecology, etc. I also teach Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, within the degree of Medicine. In terms of networks, I’m the president of the Latin American association of mutagenesis. That’s more or less my day to day 🙂

What has your experience been as president of the Latin American association of mutagenesis, carcinogenesis and environmental teratogenesis?

I had the chance to participate in several events related to this association already as a student. The first time I attended one such event – in Mexico in fact – was to present the preliminary results from my undergraduate work. Every two years (since the meeting is biannual), I would present something more updated. I’ve been involved since very early on in my career, and now I’m privileged to be president of this association. We’re now organizing the upcoming event, for next year on April, which will take place in Bolivia. In Bolivia there aren’t many groups working on this topic. On the clinical side, it’s only my group working on this topic. On the molecular biology side, there’s another group in Cota Cota, in La Paz.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Bolivia?

Currently we work with several groups. One of the main collaboration is with groups in Sweden – our work mostly takes place in Bolivia, because we have many populations who are exposed to the hazards I previously mentioned. We organize workshops together, and with the COVID-19 pandemic, I think remote conferences and webinars gained momentum, and we have definitely incorporated this. Currently I have another project funded by UNESCO, which focuses on arsenic exposure. Most of my collaborators are geologists or geochemists for this project. I focus on the clinical and public health aspect. Regarding the topic I study, there are many countries where genetic toxicology is a topic of great interest -this includes Mexico, India, Argentina, and Bolivia. In the case of Bolivia, exposure to arsenic is not mostly caused by mining activities, but rather by natural processes – with time, natural metals have been released into the water, and people consume this polluted water. Our population, especially those from Uru murato ethnic group have a protective phenotype – genes that allow them to efficiently eliminate arsenic – so they don’t show toxicity signs typical of arsenic exposure, including skin cancer.

Who are your scientific role models (both Bolivian and foreign)?

Dr. Luis Miguel Romero, my undergraduate tutor, is one of them. Now he is no longer fully dedicated to science – he is now a bishop. He was very influential in my career, and a great guide from the moment I was an undergraduate student. He gave me great freedom and this allowed me to become an independent scientist. Other scientists in Bolivia include Dr. Elsa Quiroga, who is a PhD in Mathematics. She has a great capacity to understand science from the point of view of various disciplines. Together with me and other colleagues, she was one of the founders of the “Asociacion Boliviana de Mujeres en Ciencia” (Bolivian Association of Women in Science). We organized several conferences and workshops focusing on inter-disciplinary approaches. I think these were very useful because sometimes one lives in one’s own bubble of a topic. Elsa has a great capacity to find the links between the different disciplines and to understand the language of all these disciplines. From abroad, one of my role models is Dr.Marie Vahter, an expert in arsenic. She is now retired, but she still participates in various research projects.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Bolivia, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

At the beginning of my career, it was obvious that women were neglected in terms of career. Unfortunately, Bolivia still faces significant misogyny. Nevertheless, there are now more initiatives and incentives to promote and support women in various different fields, including science, politics and other fields. Women are also showing a lot of commitment, so things are changing.

What is your role in the Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World?

I am a Full member, and for instance last year I organized the first event in Bolivia, with the participation of various colleagues from various areas of Bolivia, and with the support of UMSA. Due to a lack of time I have unfortunately not participated in many activities they’ve organized but I do participate, as much as I can, in trying to promote the engagement and involvement of women in science and research.

Are there any historical events in Bolivia that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

Discrimination is a huge issue: to women and to indigenous populations. This has changed slightly nowadays.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Bolivia?

I’ve traveled to many places. I also love languages, so this makes interactions easier. I speak English, French and German relatively well, for instance. It’s always challenging to face cultural clashes. Perhaps where I’ve felt it more was in one of my trips to India, when I was invited to give talks relevant to my area of expertise.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

I mostly use light microscopy, combined with conventional staining like Giemsa, DAPI, etc. Perhaps fluorescence microscopy is what I like the most. It allows me to see the “comets” I previously mentioned 🙂 I’ve never worked with EM so I can’t say if I would like it.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

Exchanges between sister chromatids in CHO-K1 cells! It was beautiful to watch.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Bolivian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Well, from my type of work and expertise, I’d say, if you’re planning on becoming a microscopist, know that it can be harmful to your eyes and your vision. If you spend too many hours at the microscopy – which is relatively normal in this discipline – it will take its toll. Now beyond this health advice, you should do what you’re most passionate about, while taking the necessary precautions. Take care of your body so you can perform well as a scientist. Take care of your position too while sitting at the microscope! Other than that, follow your passions.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Bolivia, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I’d love to continue training young scientists who like microscopy. Perhaps in the future as a country, we can invest in infrastructure and bring novel techniques to the country, and support novel lines of research. For example, currently we only have 2 EM microscopes in Bolivia as far as I know. I hope this change, and I hope this contributes to scientific development in the country.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Bolivia a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

I travel a lot in Bolivia due to the nature of my work. There are many places in Bolivia which are natural wonders. I really like Potosi and the lagoons, and Los Yungas, Beni, Pando, Santa Cruz, Isla del Sol, the Uyuni salt flat, etc. There are many places with beautiful landscapes and natural wonders. Perhaps the one thing we Bolivians enjoy a lot when we go abroad are beaches, as we are a landlocked country. But we have beautiful lakes and lagoons.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)