An interview with Helen Spiers

Posted by Helen Zenner, on 18 September 2023

Citizen science is a fantastic way to engage the public with scientific research by getting them involved with real research projects. For scientists, the power of the crowd can help them overcome analysis bottlenecks that might otherwise slow the pace of their research. Martin Jones and Lucy Collinson, from the Crick Electron Microscopy Science Technology Platform, teamed up with Helen Spiers to create a project to get citizen scientists to annotate their EM images. You can read the background to the project, Etch A Cell, in the blog post from Martin and Helen in 2020. Having seen the project grow over the last three years, I thought it was the perfect time to catch up with Helen to find out about her career path and her work at Zooniverse, to get an update on the Etch A Cell project and to discover her tips on creating a successful citizen science project.

What is the Zooniverse, and what is your role there?

The Zooniverse (www.zooniverse.org) is a platform for online citizen science. It enables members of the public to contribute to real research projects. So far, through the Zooniverse, more than 2.6 million registered volunteers from around the world have contributed over 766 million classifications to hundreds of research projects. These projects span a breadth of subjects, from ecology to astrophysics, to the humanities and biological research, amongst others. Today, there are nearly 100 live projects on the platform, with recently launched projects covering topics such as searching for life in the universe (‘Are we alone in the universe’), studying species in underwater images (‘Spider Crab Watch’), monitoring forest restoration efforts (‘Tag trees’), and deciphering medieval manuscripts (‘Deciphering Secrets: Unlocking the Manuscripts of Medieval Spain’). I first joined the team as Biomedical Research Lead and postdoctoral researcher, and was based at the Department of Astrophysics at the University of Oxford. This involved working closely with multiple research teams around the world to help take project ideas from conception to launch, in addition to studying meta data produced by the Zooniverse to further understand the domain of citizen science. This role has evolved over the years – while I still provide assistance and guidance to diverse biomedical research teams considering applying citizen science to their research questions, I also support and develop the portfolio of Etch A Cell projects, now known as ‘The Etchiverse’, based at The Francis Crick Institute. I’m now funded by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative on their Imaging Scientists program (https://doi.org/10.37921/838824xbrqxs)

Can you tell us about your background?

I did my undergraduate degree at Oxford University, where I studied molecular and cellular biochemistry. After graduating, I worked as a medical writer for a couple of years – this involved writing for a range of materials across diverse healthcare subjects. Following this, I completed a PhD at the Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre at King’s College London, where I studied developmental epigenetics. After I finished my PhD I started my role with the Zooniverse team.

We heard from you and Martin Jones about Etch A Cell in 2020, what’s the latest on this project?

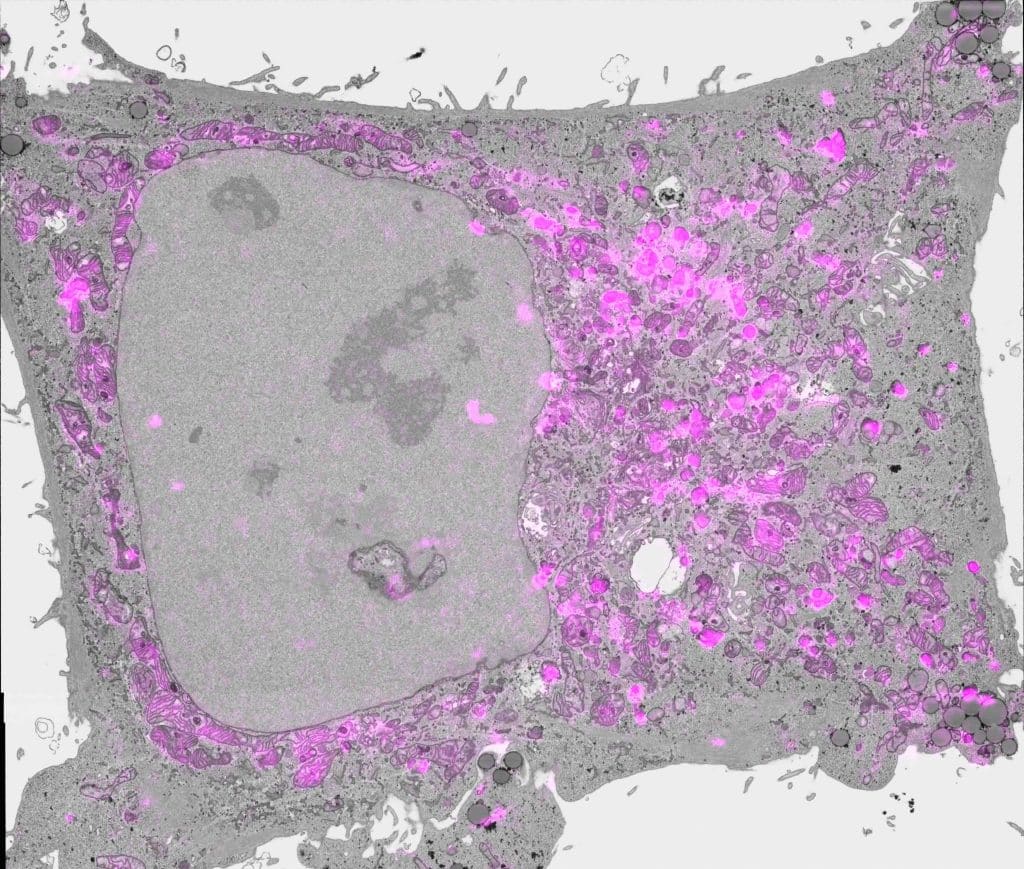

We’ve built quite a few projects over the last few years! When you last spoke to us, we were tying up the analysis from Etch A Cell, our first project where we asked volunteers to contribute to the segmentation of the nuclear envelope. Since publishing that work (https://doi.org/10.1111/tra.12789), we’ve developed and shared many other Etch A Cell projects which ask citizen scientists to help us examine different organelle classes. Through Etch A Cell – Powerhouse Hunt, Zooniverse volunteers are helping us study mitochondria morphology. In Etch A Cell – ER we are studying the endoplasmic reticulum in collaboration with the Organelle Dynamics Laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute run by Jeremy Carlton. We’re studying multiple organelle classes in a single data set in collaboration with multiple research teams across Ireland and Australia in Etch A Cell – VR. In Etch A Cell – Fat Checker we’re studying lipid droplets with researchers at Mayo Clinic and the University of Minnesota. More recently, in May 2023, we launched Etch A Cell – Demolition Squad, our first project using correlative data to study lysosomes. We’ve also got a few new projects in the works, and recently published a paper on the subject of applying online citizen science to the analysis of biological volumetric data, with the aim of inspiring and supporting other research teams considering adopting a citizen science approach. Looking to the future, we’re always open to new collaborations and helping other teams get started with citizen science.

Did you have any problems that arose during the Etch A Cell project that you didn’t anticipate; were there any unexpected positive outcomes/surprises?

A central aspect of online citizen science is asking multiple volunteers to classify each ‘subject’ (the single unit of data to be examined) in a project, as it is through this collective effort that we can generate very high-quality data for further analysis. Following data collection, downstream data analysis first requires a step we call ‘aggregation’: combining multiple classifications associated with a single subject to form consensus. For Etch A Cell, this process proved to be one of the more challenging aspects of our project pipeline. This was, in part, because Etch A Cell was the first project to use the freehand drawing tool on the Zooniverse platform, hence, no pre-existing approach had been developed that could be quickly applied to the analysis of the data produced, and when we started working on developing a new aggregation approach for this form of data it wasn’t straightforward. Despite this challenge, one positive outcome of this work was the very high quality of the aggregated data produced from the collective effort of volunteers! Go team!

Do you know who your ‘average’ annotator is?

In short, no, not for the Etch A Cell projects. The Zooniverse doesn’t ask volunteers to share any demographic information when they register to contribute (and it is also possible to classify on Zooniverse projects without being registered or logged in – to lower the barrier to entry as much as possible). Hence, we don’t obtain demographic information for our participants.

Will your models and training data be freely available?

Yes! We share everything produced from the Etch A Cell projects upon publication. From our first Etch A Cell project we shared the following:

| Output | Example |

| Raw image data | www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/empiar/entry/10094 |

| Raw volunteer data | www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/files/S-BSST448/classifications.tar.gz |

| Raw expert data | www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/files/S-BSST448/Expert |

| Aggregated volunteer data | www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/files/S-BSST448/Aggregations |

| Aggregation code | www.github.com/FrancisCrickInstitute/Etch-a-Cell-Nuclear-Envelope |

| Machine learning code | www.github.com/FrancisCrickInstitute/Etch-a-Cell-Nuclear-Envelope |

| Machine learning predictions | www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/files/S-BSST448/Predictions |

How can scientists get involved with the Zooniverse?

Anyone who is registered with the Zooniverse can build and share a project for free using the Zooniverse Project Builder. Through this online interface it’s possible to upload project data, design project content such as Help Text, Tutorials and Field Guides, and to design the series of tasks volunteers will be asked to complete in relation to the project data. A finished project can then be shared through a variety of different pathways: directly and privately with collaborators by adding them to the project via their Zooniverse username, alternatively, a project may be made publicly visible and shared via URL, or the project owner can apply for their project to be shared on the Zooniverse platform, which is a process that requires multiple review steps with the Zooniverse team and volunteers. Beyond building a citizen science project, there are also other opportunities to get involved with the Zooniverse – some of our contributors translate projects so they are accessible in other languages, we have a community of researchers who actively share Zooniverse-relevant code for re-use by other teams, and it’s also possible to contribute simply by classifying on Zooniverse projects, discoverable here.

What are your top tips for designing an effective citizen science project?

First, take a good look at as many citizen science projects as you can, both on the Zooniverse and beyond. Second, get started building quickly and iterate on your design – it’s much easier to improve on a draft. Third, get lots of feedback – show your children, show your Granny, listen to everyone about what could make your project better.

Thanks to Helen for sharing her tips and tricks for designing citizen science projects. As The Etchiverse continues to flourish, hopefully it will inspire new citizen science projects using microscopy data. Look out for more posts on FocalPlane from Helen and the Etchiverse team over the coming months.

(1 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

(1 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)