An interview with Iván Rey

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 14 November 2023

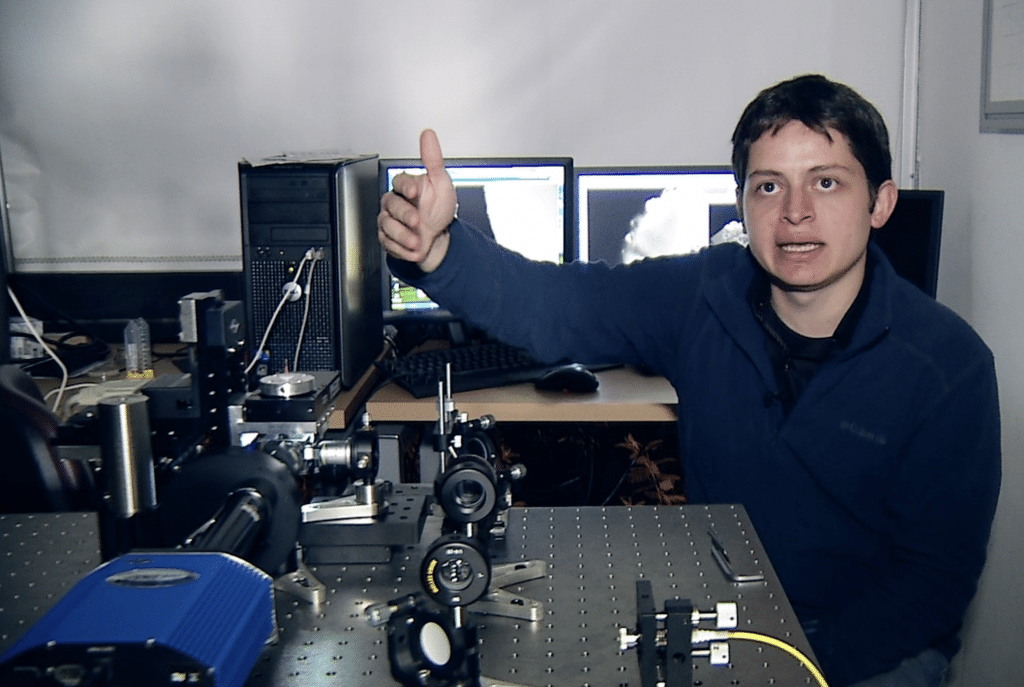

MiniBio: Iván Rey Suarez is a postdoctoral associate at a joined position at Universidad de los Andes in Colombia, and the Institute for Physical Science and Technology (IPST) at the University of Maryland, where he focuses on studying the mechanobiology of the cytoskeleton. Iván developed a passion for nature and for physics since an early age. He went on to study Physics at Universidad de los Andes, where he eventually did a thesis on biophysics. Then he went on to study an MSc degree in Biomedical Sciences, also at Universidad de los Andes, and during this time, he did two internships in France and Denmark, where he first used microscopy as part of his research. Before embarking into his PhD, he participated in building the first light sheet system in Colombia in 2011. He received a Fullbright scholarship to do his PhD in the USA, joined between labs at the University of Maryland and the NIBIB – NIH. During this time, he used his knowledge in biophysics to both, build and use novel imaging technologies to study the cytoskeleton. Iván is currently a member of the Latin America Bioimaging executive committee, where he hopes to help encourage the integration of Colombian scientists to the growing network of microscopy in the region, facilitating access to infrastructure and expertise, as well as to contribute to developing science and technology (infrastructure and human resources) in his country and in the region.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

As a young child I always loved to observe nature – under rocks to see what animals were hidden. I loved animals too, and it helped a lot that my parents always nurtured my interest – they would give me books and I’d just read them non-stop. I had my obsession phase for dinosaurs. Later, at some point they gave me a book about astronomy – it was a lovely book collection of short stories, which is great for the attention span of young children. This of course influenced me to lean towards Physics. A few years before finishing high school, I decided I’d pursue the career of Physics. It’s interesting because at some point in my Physics studies, I re-encountered my love for Biology, with the subject of Biophysics.

You have a career-long involvement in biophysics, mechanobiology, and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

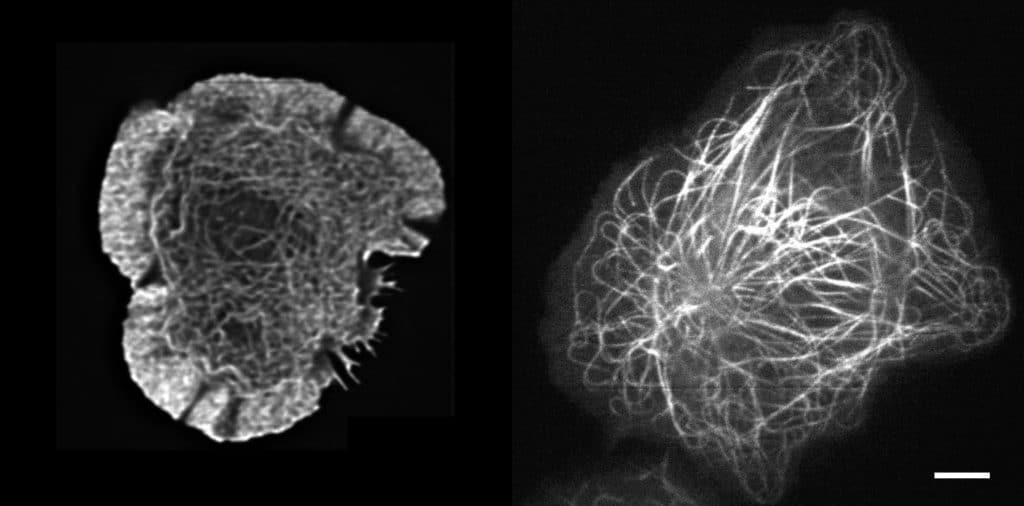

Here in Colombia, in the BSc of Physics, one has to write a thesis. I spoke to a couple of professors, to express my interest about doing my thesis in their labs: one was a professor from India who focused on quantum physics, and the other was a professor from Mexico, who had just moved to Colombia and was working on Biophysics. I thought it would be interesting to measure the angular momentum of light by using a biological system. When I told this idea to the Indian PI (working on quantum physics), he discouraged me – he told me everything about this had already been done. But when I spoke to the Mexican professor, he told me it sounded like a great idea, but he said the implementation might be challenging. So he proposed another set of ideas related to biophysics, all of which I found really interesting. This moment is key for me to collide with Biophysics as a final decision for my specialization. I started working with him, on synthetic systems that emulated the cell membrane. The fascination for the cytoskeleton I have now started with a video taken in the 1960s, of a neutrophil chasing a bacterium. I started wanting to understand what this video was about, and how the cytoskeleton of the cell allows the cell to move and change shapes. It’s a system of proteins that self-assemble. When I became aware of all the complexity regulating this movement, I thought – this is what I want to specialize on! This led me into the field of mechanobiology, where I focused on the cytoskeleton, and as we know, microscopy plays a key role. I had had a first approach to microscopy when I was using the synthetic models of the cell membrane – I did an internship in Denmark, and one in France, where I learned about light sheet and confocal microscopy. In my last year in Colombia, before I went abroad for my PhD in 2011, I worked with a different PI, Manu Forero at Universidad de los Andes, to assemble the first system of light sheet in Colombia and as far as we know, the first one in Latin America. I actually noticed that you interviewed Federico Brown, who is now in Brazil- he was one of the first users of our system. We looked at samples brought from Ecuador, and we did the bright field illumination with a bench lamp and the excitation of DAPI with a laser pointer of 405 assembled with adhesive tape… it was very frugal. At the beginning, the funds we got to assemble this SPIM system were very low. So anyway – that’s how I entered the world of microscopy, and that’s how my fascination to study cells using microscopy has been key in my career.

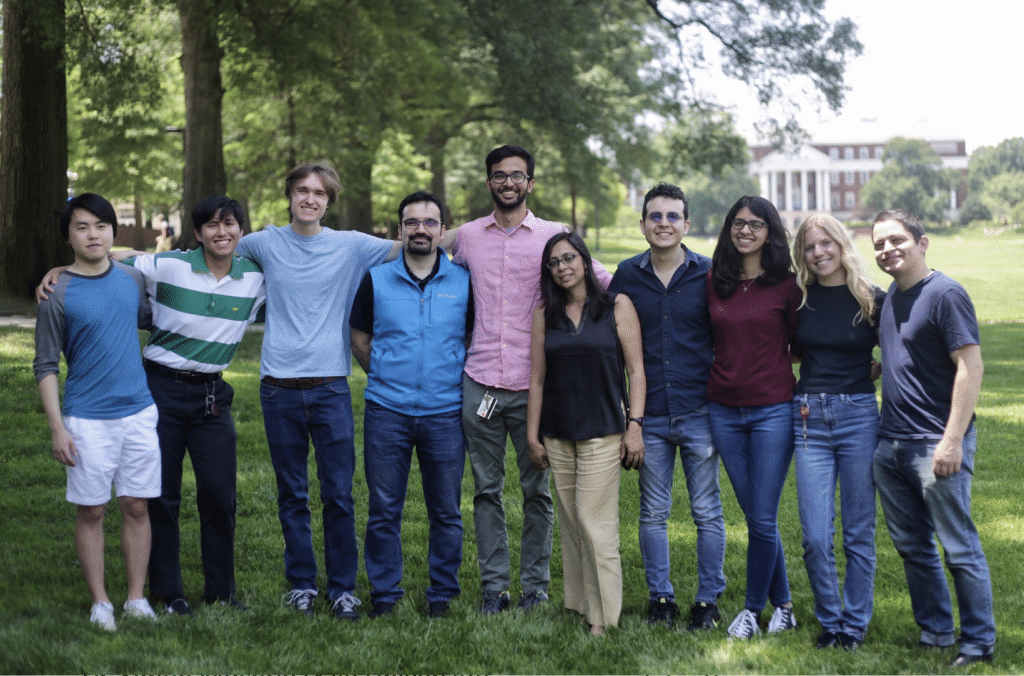

Regarding my academic road, after graduating from the degree in Physics, I did a Masters degree in Biomedical Sciences, which was at the time a degree coordinated between two Universities: los Andes and Rosario. During this MSc degree I did the internships in France and Denmark. My MSc thesis was based in a research project that arose since my BSc thesis. It was in collaboration with a professor in mechanical engineering and professor of physics. I’ve always loved collaborating. During my PhD, I had the chance to work on cellular mechanobiology in Maryland in the lab of Arpita Upadhyaya, and I had the chance to do a rotation in the NIH, in the NIBIB- National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. There I worked with Hari Shroff -his lab has produced a lot of very successful systems, like diSPIM – so while I had had a little bit of experience in instrumentation, when I got to his lab, I learned a lot more – it was full of instrumentation and cameras. This was a wonderful experience. I saw the model study in the lab in Maryland was the formation of immunological synapses between T and B cells. I proposed to both PIs to collaborate with both labs, to study the system with unique microscopy techniques. This became my PhD project. To do my PhD, I received a Fullbright scholarship. This funding was very important for me to do my studies in the USA. Part of the commitment with the Fullbright scholarships is to go back to one’s country of origin, and bring back some of the knowledge and experience learned abroad. I finished my PhD right during the pandemic, and this made traveling and relocation very chaotic. So I decided to stay on as a postdoc in the same group where I did my PhD studies in Maryland, for some time. I started a new project, but when I had to come back to Colombia, the completion some of this work remained pending. So I currently have a joined postdoc between the Universities in los Andes and the University of Maryland. I am very lucky to have been able to maintain connections with my country. In 2015-2016 I participated in the organization called Clubes de Ciencia, which require a local partner (in the country of origin). So I worked with Manu Forero and together with him, we spoke to Manu Prakash, to use the Foldscopes for a series of workshops in Colombia. He donated many, and so we did the workshops in collaboration, and this allowed me to establish long-lasting connections with Colombian scientists and students. Right now I am here in Colombia and many of them are abroad pursuing their careers. I wasn’t able to do this many years, because it’s very time-demanding and I was doing this during my PhD, and so basically using my holidays to do the workshops. But during these activities I became aware of the importance of reaching young students, and the challenges of keeping them interested and engaged. We were working with students of between 14 and 16 years of age. So this made me appreciate my teachers of my early education – one realizes how impressive their work really is. I think this type of engagement is very important, because at this age they don’t have a great idea of what a scientists does – not even how they look like! The image they have of a scientist is the picture of Einstein with crazy hair. For them that’s a scientist. This or the image that cartoons seem to perpetuate, of a mad scientist in a lab coat among many fluorescent tubes. So when they would meet us, they’d realize we’re just normal people, who love speaking about the science we do.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Colombia, from your education years?

I have very good memories of many of my teachers from primary school, including many who really captured our attention. Towards the end of my high school studies, I joined a school which wasn’t great. So I suffered a bit of a shock when I entered university, because Universidad de los Andes is very demanding. A person who had a huge impact is the Mexican professor I mentioned earlier, his name is Chad Leidy – he gave me a chance to learn about science: how it’s done, what instrumentation is used, how to pose research questions. To me he was a great mentor for many reasons including how he taught things: with continuity and coherence between the different things he was explaining. I feel not only me, but many other people, regardless of whether they are academics or went to industry, were greatly impacted by him.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Colombia?

Sadly, no. This is something that LABI has encouraged me to pursue now. Sometimes some barriers feel unsurmountable. I think many conversations can begin virtually – telecommunications have greatly reduced distances, so this has really led to a revolution in collaborations. But I haven’t had the chance to work with other Latin Americans. While I was in Maryland and NIH, I didn’t meet other Latin Americans who were in similar fields. In conferences perhaps I could have actively established connections with other Latin American scientists. Sometimes, when we are young don’t think far ahead, and we are perhaps intimidated about leaving our comfort zones especially during huge events like conferences. So I would stay around my group of colleagues from the same lab. I think only later one realizes this in retrospect.

You are now a member of the LABI executive committee – how has your experience been? Why did you decide to join and what are your long term expectations in the role?

So far, I have provided local information, and support with processes such as reviewing applications for calls for grants to participate in courses, or exchange of experience visits of scientists to an imaging core in a different country. I only recently joined so it’s a relatively new role for me. In the last meeting, I was invited to participate in the preparations of the next LABI meeting. So I want to become as active as I can in this role. After the meeting I realized one of my responsibilities in the role is to facilitate connections between Colombian scientists and other Latin Americans via LABI. I hope to generate a stronger connections between Colombia and the network, and support in the various endeavours, projects and meetings under the umbrella of LABI. I find all the initiatives currently in progress essential, especially figuring out what the various countries need in terms of technology and infrastructure and how to establish it. But I’m also still reconnecting locally, so I will be attending various conferences in Colombia to map better what the landscape is and forge connections.

Are there any historical events in Colombia that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

I think historically, unfortunately, science has not been a priority in Colombia. There are many other problems that have taken priority – for instance, around the 1950s, there was a huge wave of violence whereby the two main political groups started persecuting one another and each other’s supporters. Around this time my maternal grandfather had to leave Colombia because he was active in politics, and the opposite party to the one he supported, came to power. So he had to leave. We also have problems of guerilla, paramilitarism, drug-dealing, issues with inequality, etc. The sum of all these situations, which are so complex, make it difficult to dedicate much attention or funding to science. It’s difficult to ask the government for half a million dollars to buy a new microscope to study the structure of the wings of a butterfly, or the cytoskeleton changes of a cell. It’s unrealistic given the country’s profile. It’s a barrier, but despite these problems, we have gone through a process of evolution where we have had to overcome these challenges. At present, Colombia is in a much better situation than it was back in the 1980s or 1990s. Things have improved, and so I think eventually these improvements have to be accompanied by investment in science and technology. The Colciencias was recently turned into a Ministry – I don’t think this was accompanied by an increase in funding, so this made things a bit difficult. Nevertheless, I think things will continue to improve – there are currently new calls for funding which I think have lots of potential. I think also that State-based funding is not enough – further private investment is required. But overall, science has never been a priority in the country. This is not specific to Colombia, but common to many Latin American countries. I think all our countries are going through a process of development, going from being producers of primary products to developing technologies, which lead to better development – it’s a self-feeding loop. On this topic, I also think we need to better communicate the importance of science to decision-makers in the governments. I think there are two disciplines that should be created or better developed: one is a) scientific journalism, because many times a scientific discovery is re-interpreted by non-scientists in a way that it becomes something else – it gives false expectations to the public, and this eventually leads to loss in trust for science, or to the general population getting the feeling that scientists just waste money. We should better inform society about what we do – they should be more conscious about what the scientific process is – and that science is not like in the movies. This will help because at the end, it’s the general population which chooses those in power, so if the general population better understands what the relevance of science is, they will demand that the people they choose as representatives consider those issues and include them in their policies. The other is b) scientific policy and lobbying. I remember that in Colombia a big issue for research was that since there were groups internationally recognized as terrorists, there were many restrictions on what reagents could enter the country and to whom they could be delivered. If one would ask for reagents or materials as varied as chloroform, or Galvo scanners for microscopes, and people at customs would think this was for building a bomb or other forms of weapons. People at customs don’t know what the scientific applications of these resources are, and so reagents would often be held in customs for months. In this case, I think policy that could facilitate the entry of scientific reagents would help science in Colombia tremendously. This is a huge barrier for us: getting reagents from abroad at all.

Who are your scientific role models (both Colombian and foreign)?

Chad Leidy is definitely a role model for me. He is not Colombian, but at the same time he is ☺ He is Mexican-American but we’ve adopted him now. He placed a lot of importance on teaching. He closed the gap to reach young students – and this had a huge influence in a generation of scientists. He broke barriers, and I admire him for this. I also admire Julie Theriot whose studies in the cytoskeleton are super-important. In mechanobiology, I admire Viola Vogel’s and Jonathon (Joe) Howard’s work on the cytoskeleton. The impact their work has had is huge, and there are many PIs now that are alumni of their labs. They are like nodes in a tree, where important branches derived from. I also admire Arpita, she was a great PI and she is a very nice person, she made me believe that is possible to have a balance between leading a good research lab and having a good life.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Colombia, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career both at home and abroad?

Twenty years ago when I started my BSc in physics I remember there was only one female student out of ten incoming students. I also remember there were only two female physics faculty members at that time in Uniandes. Today that has changed considerably and there are six female faculty members and I think more women are joining physics programs. I also remember that my PI at Maryland was one of the few female physics faculty. I think that gender balance (in physics particularly) still needs to improve both in Colombia and abroad.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Colombia?

When I was in France, the language was an important barrier. In the USA, maybe the language was also a barrier. In general, I think if one is open to learn how other cultures do things, this facilitates integration. This is at a cultural level. At a scientific level, my experience abroad was very positive. If I ever knocked on any door, it was always open – there was a time when I had access to 3 labs at NIH and Maryland. This made my work super exciting, and of course had a huge impact in my research.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

In general I love all techniques, especially those that allow you to acquire volumetric data – to see everything. So light sheet is one of them, and new confocals with structured illumination as well. Those are the techniques I like most. There was a time when I would acquire images with TIRF, and this allowed me to see the surface contact points between cells. Later, analysing similar samples using confocal microscopes, sometimes what seemed as two different cells making contact, was actually one cell with two contact sites. One could be missing a lot of information if one only uses 2D. But this comes at a cost: many of the systems optimized for volumetric imaging achieve lower resolution than the one you can achieve using TIRF. So structured illumination closes the gap between both things. You can see things in 3D in great detail. I think it’s an important technique.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy?

Something that made a huge impact is that I had worked with synthetic systems of lipids here in Colombia. When I started my PhD one of my first missions was to establish a system for single particle tracking for receptors moving in the membrane. So the first thing was to make a supported bilayer where we would add antigens which would be detected by receptors. I did tests to measure single particles in this system, before trying to do the more complex system involving cells. I remember one of the first things I acquired images (acquired at a high rate, with 30-35 images per second) I saw lipids moving randomly, and I thought “wow, this is happening in the surface of each of my own cells”. This was an eye-opening moment for me.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Colombian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

I think that it’s super important that if you meet Colombian scientists whose work you are interested in (or any scientist for that matter) – contact them! When I receive requests from students who are interested I my work, this is great and I always have my door open for this, and I also help them get in touch with other potential leaders in the area whose work is relevant to the student’s interest. Don’t be afraid to approach and ask because people, even when in science we are all very busy, there is a lot of interest in community-building and mentoring. I think this is true in general, and in microscopy. So approach people, attend courses, get involved in projects.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Colombia, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

When I see institutes such as those in Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, I dream of one day having similar research centers (funded by the State) which are at the service of investigators in the entire country, and which allow access to all types of equipment, and to people with different expertise. The experience I had at the NIH, with the intramural research program, made me realize this is extremely important. I’m not sure what the steps are to make this happen, but a first step is maybe find the scientists specializing in microscopy in Colombia and together forms networks and write a proposal for the government. I would happily participate in such initiative, whether I’m here or elsewhere in the world. It’s vital to strengthen capacities at a national level.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Colombia a special place?

The people- people are wonderful. There’s something in the air which is very nice. Bogota is a big city, with 9-10 million people, which can sometimes be a bit too much, but in general, people make it a special country. In the spirit of Colombians, there is a lot motivation to improve, be active, develop. So one feels happy here.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)