Enhancing Global Access: interview with CZI grantee Michelle Itano

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 24 January 2024

ENHANCING THE ROLE OF A MICROSCOPY CORE FACILITY TO CATALYSE BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH

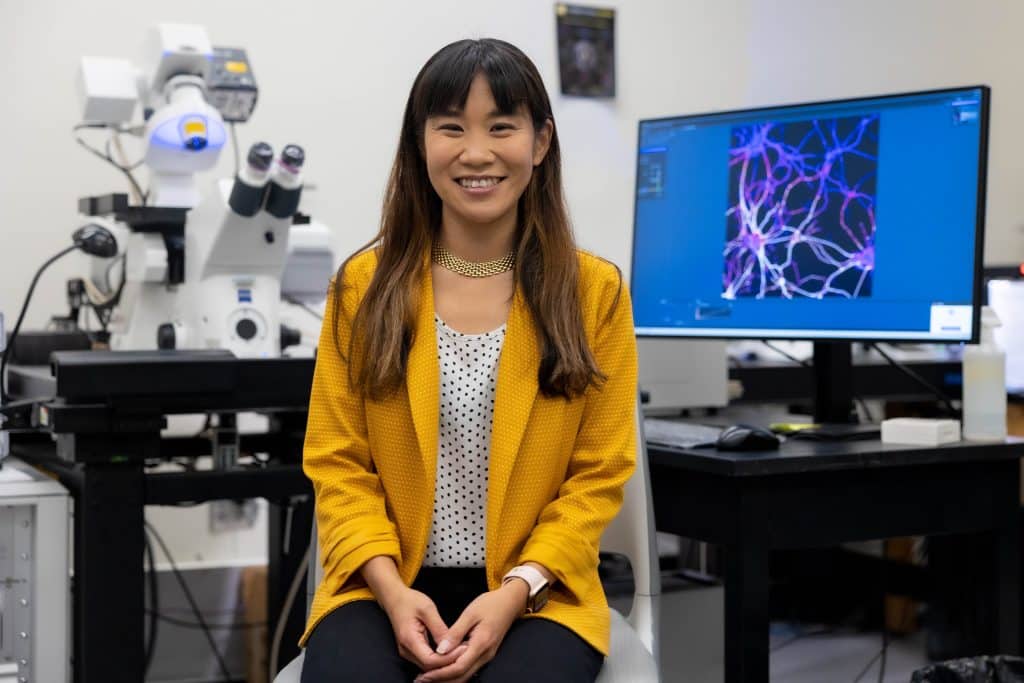

Michelle Itano is a cellular biophysicist and Director of the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Neuroscience Microscopy Core. Her project for the Cycle 1 Imaging Scientists CZI funding call aims to actively engage and grow collaboration between researchers and computer scientists to design pipelines to generate and analyse large imaging datasets. In addition to her work at her institution, Michelle Itano is a key member of Bioimaging North America (BINA) and Global Bioimaging (GBI) in several capacities, aiming to ensure global access to microscopy resources.

What was the inspiration for your project? How did your idea for the CZI project arise?

I wrote the CZI grant very soon after starting my position as core Director. I really liked that it was essentially written for core directors. You were supposed to be teaching, interacting with builders, students and users. We were already doing this, but the CZI grant would enable us to do so with a broader reach. We had started a project using DISPIM microscopy, to figure out how to get more isotropic imaging in cleared tissues. This required us to figure out how to handle data management and analysis. This brought us to OMERO, and we started working more closely with out IT specialists to figure out how to analyse the data in large scale. These relationships grew into the data management projects we have now. These were specialized collaborations that we were able to devote more time and energy to once we connected with the right people. To me, the main difference with CZI is that I was trying to do everything by myself. We were a one-person core and historically had been so. But this was no longer sustainable. I couldn’t have kept instruments coming in, users imaging, supporting training, and having these collaborations without more staff.

Your original project focused on core facilities, but you are currently very active in several other large projects and networks such as BINA, GBI and PAIRUP. How did all this evolve from your original project?

When I started, we used to serve users that were in IDDRC grants only, and most of them were also in the Neuroscience Center. That was about 20 labs or so. Now we have about 100 labs, and 200 individual users. So we went from being largely a departmental core to being open to many more people, including external collaborators. Regarding our outreach efforts, I think that’s when having additional staff and more time was key. Also, being linked to CZI allowed me to see that there were other things going on, including becoming aware of the existence of GBI and BINA. When I wrote the CZI project I didn’t know these other networks existed, but I was excited about the opportunity to meet with other people who were really invested and have the same values. Honestly, I get much more than the time I give. It has allowed us to build many relationships – experience and expertise is shared so generously among the various members. Honestly, I think of it also as professional training for myself – I see how other leaders teach and benefit from their material and their expertise. UNC was kind to give me an avenue to start workshops and courses too, and there was a lot of hunger for it. People were very happy to see someone willing to step into that role. Everything is so global now, and the different fields move so quickly that you need those collaborations in order to really address specialized questions. I’m embracing the fact that I might not have all the knowledge, but I might be able to find somebody who does. That’s now my role: active listening to people, and connecting them to others that might have that expertise, or the advice that my users are really seeking.

How do you see the future of core facilities and their value?

I started on social media for the for the first CZI meeting, because they asked us what our handles were. It happened before the COVID pandemic and it was key for me at that stage of developing the vision of what our core facility would be, to see other examples of other facilities, and connect and get really rapid advice and input from the global community. I did a lot of just observing at the beginning. It allowed me to see what elements of research people were doing at their cores, what workshops and teaching, and it led me to ask myself what role we could have. After that, the more I started posting, the more users and students became aware of the possibilities of the role. They would say ‘I didn’t know you could teach at a core, or you could develop curricula, or you could go to conferences without being tenured track’. It encouraged me to keep sharing because I realized that many young scientists only get a very narrow view of what a research career can be in academia. I wanted them to see the possibilities. Regarding my involvement in BINA, Alison North told me that her super-power is to get people to say ‘yes’. She asked me to chair the BINA Communications working group even though I had no idea I had good skills in communication. I thought ‘why not’.

What is the unique value and impact of the CZI program? Is there something that makes it unique compared to other grants or other types of funding?

CZI carried such a big name to it, and I was the first CZI grantee at UNC. I got to meet with lots of the leadership people, the vice-chancellors of research, wondering what are the CZI goals, what is unique about this funding mechanism, why is it so exciting? It was fun because I got to tell them ‘the focus is really on the people, connecting people, and not on the paper or something that has already been done. It’s on possibilities, and connecting and building communities’. I think UNC has been really interested in that, and being a CZI imaging scientist has led me to more roles in the vice-chancellor’s office. For instance now I sit in the Dean’s meetings – it brings me out of the department center role and more thinking about research across the campus. I found that it allows me to be on service roles, but I also get to be on search committees. In many of these committees my presence is now valued because we have a pan-experience of research on campus. Also we have more time to devote to university services because we are not on the tenure clock, we have more time to teach classes on rigor and reproducibility, I get to be a mentor too. I think once university leadership finds that those values align, they see a lot of us in other ways – they see us as strengths that represent more than just a figure in a paper, which might have been the prevailing mindset in the past. With regards to my project, the CZI grant has been the key. Many of my core colleagues have been trying to increase their staff for years and never got approval to open a position. But because we got several years of funding through CZI, it enabled us to open that position and with that, justify further growing our team. Beyond this, CZI has been incredibly generous in listening to what we thought some of the critical issues to address were – what we thought would have the most impact immediately. It’s the opposite of other funding organizations which support what you have already done. Instead CZI funds the project you wish you could devote more time to. They ask ‘what do you need to make it happen?’ and then were flexible while making it a reality, with visits, administrators, organizations, workshops – they are very open minded to what everyone’s vision might look like.

What would you say is the overall long-term value and impact of the CZI program as a whole, through its different calls?

There’s been nothing else like it: to elevate the status of people who had been overlooked in the academic and research sphere. Or a lot of assumptions were being made by institutions and fields about what the capabilities and impact of core scientists were, and CZI has changed that. The fact that they didn’t pick people who were developing their own research, but balancing a range of things are cores, sent the message that this in and of itself has value. It also sent the message that the broader we get, the stronger we are. The fact that they have funded many scientists shows there was an unmet need. There is so much worth out there, waiting for someone to take a chance on it and CZI did this. They have shown that a little bit of impact and attention and elevation can have huge resounding ripples across the field and across institutions. This is a new lesson. They CZI investigator status is more of an award or an endorsement, sending the message that this role we play is important and should be invested in. They also invested in administrators and program managers who know intricate details about the community – this role helps bring things together faster. Now I see NIH speaking about funding program managers, which shows they realized the value of this. So the CZI philosophy is starting to trickle down – they don’t focus on PIs, but on fostering collaborations and using everyone’s expertise in a non-hierarchical way. What matters is the impact that people are interested in having in their community.

One thing discussed at the LABIxBINA meeting was professionalizing imaging careers. I think this is something that you also do. What do you envisage for the future in this respect?

One thing I love about academia is that there is space for people with different personal values to succeed. A core director might be interested in building instruments, or in evaluating/developing and contributing as a researcher, or adding utility to something. You could be someone who is an incredible service professional and enable whatever your community needs much faster, better and successfully. You could be someone interested in strategic changes at institutions, be this professional organizations, your own institution or global communities. To me a core director doesn’t need to have all these abilities simultaneously, but you need to find one set with which you feel comfortable and where you can have a lot of impact, and then it’s up to you to drive that. Hopefully you’ll be at a place that will value and encourage and support this vision. I personally like that there’s some flexibility in our career: not everyone has to do teaching or develop new technologies. So I think there’s an element of knowing your own strength – and I wish there was more recognition to these strengths. But whatever our skill, it falls within a Venn diagram of what a core director does, and no one aspect is better than others – at the end we all have a huge impact in our communities. I feel one thing that hasn’t been seen much before is the impact of service, and the elevation of a local community’s research – this is something special that elevates the profession altogether. Historically there is a tendency in academia to grow apart from one’s community the more power one gets to define policy, and I think we are starting to see this doesn’t need to be the case. But there is still a lot of institutional pressure to separate those day-to-day interactions from policy-making. I think the more we bridge that, the more career possibilities we will start seeing for people.

How did you first hear about the CZI program?

I did not know much about CZI before the call. My center Director brought it up to me and suggested applying – he emphasized the flexibility and the novelty of the program. Otherwise, I think I would have missed the opportunity. I think I first assumed I wasn’t goint to get it. I knew so many fantastic scientists that were applying. Even when the successful names were published, I knew many colleagues who would have done as well or better with the funding. Knowing this was very humbling and there was a lot of gratitude. Because it was the first call, I think the program managers were still getting hired, and the pillars of CZI as a program were just getting defined, so it was exciting to be on the ground, with CZI defining who they were when everything was still small. Priscilla Chan came to our first meeting just to listen to our introductions and this was exciting. She said ‘it’s not about us, it’s about you guys meeting each other and connecting’. There were so many big names on the list. I kept thinking this was an incredible opportunity to learn from everyone and hear what they were up to. Every time I would go to the CZI meetings, I would take notes and notes about the amazing things people were doing, and everyone wanted to do more – to expand, to connect, to get feedback. I think I didn’t realize how small my world was until I started hearing more regularly about everything that was happening around the world.

How do you define democratizing microscopy? What do you think of the need to do so and what are the future directions of your project in this context?

When I think of democratizing microscopy, I think of getting everybody to one level above. I think microscopy can impact almost every area of research and somebody’s education, from helping people understand how a digital image works and how an image is formed to developing complex pipelines with sophisticated microscopy methods. We can also take those researchers who are already operating at a high level and make some incremental progress there. It also involved making entryways into communities and spaces that we haven’t previously reached. This might take more energy and initially affect fewer people but it changes mindsets, and from that much more is possible. Areas in the world that have previously not thought of microscopy as a pillar now wonder ‘why not develop it’ especially because it can communicate ideas so effectively, in my mind even across languages. I sometimes start my lectures like this question: ‘why are we interested in art? Why are images so captivating?’ They communicate across languages and backgrounds, there is no jargon inherent to an image, there is math, but for many of us an image is something that we have a basic understanding of and our brains immediately process, so how can we enhance that even more to make it more accessible? I don’t know if I can prioritize what type of democratization is of highest value. I know that personally I feel great value in seeing people who are able to further their careers or interest in science, especially if they have been isolated in some manner – geographically, socially, or career-wise. Sometimes microscopy can be a way to push through that barrier. In my position I now think ‘how can we make funding more sustainable? How can we mobilize funds so they can be used by core directors or managers to get a catalyst effect? How can this be done less on a personal basis, and less on a specific core basis, and allow people to see the value of what funding key communities of people can bring. I think universities are not used to investing on communities. They are used to people being funded by research grants and we don’t have stable funding mechanisms to fund people connecting with people. I think if those were to develop, that would be my ultimate goal.

Did you face any obstacles during the development of your CZI project?

The first thing was getting the institution to agree to the FNA rate. It’s much lower than conventional grants, and it took several calls to leadership for them to approve it. Another challenge was hiring – it’s difficult to bring in a good person and not know for sure whether I will be able to retain them and sustain their funding. It also meant I had to get off a grant – core directors are often listed on several grants so I had to be listed on no effort, but contribution. There were lots of meetings to discuss ‘How can I say that I am funded to still do this role, but you can’t give me money for it’. Building sustainable funding was hard. The same goes to figuring out the way UNC intereprets the education and travel funds – I wondered whether they would be distributed the way that I envisioned it being once they were actually in place. Luckily CZI has been very supportive, but it required a lot of re-budgeting and cost-coding that UNC wanted. A lot of approval before it went through.

Check out our introductory post, with links to the other interviews here

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)