An interview with Juan Quintana

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 25 June 2024

MiniBio: Juan Quintana is a Wellcome Trust Fellow and group leader at the Division of Immunology, Immunity to infection, and Respiratory Medicine, the Lydia Becker Institute of Immunology and Inflammation, and the Geoffrey Jefferson Centre for Brain Research at the University of Manchester, UK. The Quintana lab works intersectionally to understand the immunological basis of the behavioural disorders observed during chronic infections, using African trypanosomes as a model infection. Juan studied his BSc in Universidad de Carabobo Venezuela, finishing in 2007. He went on to do his MSc degree at Universidad de Zaragoza in Spain in 2008, and he completed his PhD at the University of Edinburgh in 2017. Before becoming an independent investigator, Juan did one postdoc at the University of Dundee, and one at the University of Glasgow. He has had a versatile career, and during his trajectory, he has found a passion for parasitology, microscopy and cell biology. His current interests in microscopy include mesoscopy and expansion microscopy. In addition to his role as a scientist, Juan deeply values the role of mentorship, and is committed to both, mentoring a next generation of scientists and breaking barriers that impede equal access to science and resources among the scientific community. For his work, Juan was recently awarded the British Society of Parasitology President’s medal.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

Perhaps my first memory is of the natural world around me. I would spend summers in my grandparents’ house – they had a really big garden, and my grandfather in particular had a great passion for the natural world – we would spend hours in the garden watching plants under a magnifying glass: watching the leaf veins, and the cells of the leaves, and ants and other insects. I remember they had an Encyclopedia Britannica – this was all long before the era of the internet of course – and in the middle of one of the volumes, there were some transparent sheets with different aspects of the frog anatomy: the skeletal system, the muscles, the digestive system and so on. I could spend hours seeing these and learning about this. Ever since this age, I wanted to be a medical doctor or a biologist. When the time came to attend University, I joined the degree of Biology and all during my first year I wondered whether I had made a mistake and if I should have studied Medicine instead of Biology. But then laboratory training in Cell Biology began, and I was hooked. I found it super exciting to not only see cells under a microscope, but also to start realizing all of the things that could be done with them: extract proteins, extract genetic material, modify them, etc. I absolutely loved this, and at this point I knew I wanted to pursue this career.

You have a career-long involvement in cell biology, parasitology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

I studied my BSc in Venezuela, and then I worked for a while because I had to save some money. At the time, politically and economically, Venezuela wasn’t doing great, and I realized that if I wanted to pursue a research career, I needed to go abroad. So, I worked at a company in Venezuela for two years, doing a little bit of everything except science, so that I could save money. Eventually I left, and moved to Zaragoza in Spain, to pursue an MSc degree in Immunology and Cell Biology. Once there, I decided to pursue a PhD, and got accepted for a program in Madrid, but this coincided with the world financial crisis of 2008. The difficult circumstances in Spain at the time led me to undertake two years of my PhD without salary, while teaching English and Biology on the side, so that I could have an income. I was juggling too many things, and I eventually left the program. But changes were just around the corner and I found myself being offered a job in Edinburgh, as a research assistant. By this point, because of my experience in Zaragoza I didn’t want to start another PhD. I just wanted to have a stable job and a relaxed life. So, I joined the University of Edinburgh, and I loved the project that I was working on. My boss at the time, Amy Buck, encouraged me to go for a PhD again, and I loved my project so much that I decided to go for it. This experience made me realize how inaccessible the academic career path can be: even if you have a support network, it’s a hard process, but you have people around you (your family, friends, etc.) who can help you to get through the tough times. But when you’re an immigrant and often don’t have this support, it’s even harder, and this can pose a huge barrier to pursuing a research career. I think I was so excited by my PhD project because it was all about parasitology, which I developed an interest for when I was still living in Venezuela. Back home, there is a network of researchers that focuses on schistosomiasis which is endemic to the region where I grew up. There was also a department for Bilharzia, which would receive continuous cases. As an undergraduate student I worked as a technician processing samples, and I remember seeing the parasites for the first time, and thinking how amazing they were. I went on to undertake a small study with Emilia Barrios, trying to identify parasite antigens in patient samples. After this, I left parasitology for a while, but when I went to Edinburgh, the lab I joined worked with parasites again – this time, nematodes, which I have a huge passion for! The issue I had during the PhD thesis is that every time I wanted to genetically manipulate these worms, I realized we simply did not have the tools to do this. Gloria Menacher, who worked with Keith Matthews, was in the same PhD cohort as me. She was working with trypanosomes, and every time we would meet up, she would tell me about the fantastic things she could do in terms of imaging and genetic manipulation. So, I asked her to show me her work, and for the first time I saw trypanosomes swimming in culture, and, of course, developed a huge passion for them. When I finished my PhD and began looking for my first postdoctoral position, I decided that I wanted to focus on studying trypanosomes, and I was excited about working with a parasite that can be genetically manipulated. I must admit that I really enjoy moving between research topics, bringing together diverse areas and figuring out what’s happening at the interface between them. That’s led me to work with several different parasites, and it has given me the opportunity to really expand my toolbox! My newfound interest in trypanosomes led me to my first postdoctoral role in Mark Field’s lab in Dundee. There, I learned how to work with trypanosomes, and how to genetically manipulate them. Armed with these new skills, I decided that I wanted to explore how these parasites impact host health and joined the lab of Annette MacLeod at the University of Glasgow. Shortly after joining, I was awarded a Sir Henry Wellcome fellowship, which allowed me to start developing and exploring my own research questions, and this ultimately led to me being recruited as a junior group leader at the University of Manchester.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Venezuela, from your education years?

Everything! I owe everything I have achieved as a scientist, to the people who trained me and believed in me while I was a student in Venezuela. At the time, the education back home was incredible, but there are many things (political, economic and social) that have impacted life in Venezuela, including education and research. Nevertheless, when I look back, my experience was first class, and I don’t think that I’d be where I am today without that incredible start to my research career. My degree included subjects such as cell biology, biochemistry, biophysics, ecology, evolution, biotechnology, etc. The class that still stands out to me the most was my evolution class. I had a teacher on that course who was fantastic, and so inspirational. His classes are amongst those that I remember most fondly. He was a great speaker, and we would all sit on the floor listening to him speaking about plant evolution. He would raise fascinating questions and it’s something I think about to this day. He had a huge impact on me. In addition to the teaching, the reason that my education in biology was so strong is that we had the advantage of being surrounded by the natural world. Venezuela has an extremely rich biodiversity, and we have just about every type of ecosystem you can imagine, with countless species of plants, animals, insects, etc, that we could study. I feel extremely lucky to have had this start to my career.

What do you do on a day to day basis as a group leader?

I try not to go crazy! J I think my day-to-day has changed a lot since I became a PI. It has shifted from reading a lot of papers and designing experiments, and figuring out how to sell a project, how to tell a story and how to deliver engaging presentations, to lots of administrative duties and paperwork. I’m currently writing SOPs and risk assessments. I admit that this has been a difficult transition, as I feel more at ease in the lab, undertaking research. Anyway, on a day-to-day basis, I start my day with coffee! I don’t work well without coffee! Right after this, I go through my emails – I like to get that done early on. After this I dedicate a couple of hours to catching up with scientific literature. And after this it varies a lot. I supervise my students – recently one of my MSc students- Praveena Chandrasegaran, whom I am very proud of, started her PhD in Edinburgh. She started her work with me when I started my fellowship as a junior group leader, so we were both a bit ‘green’, but she is so smart! I love discussing science with her to this day, and I think that she has a bright future ahead. Then there’s Agatha Nabilla, who is also amazing, and is great at coding and bioinformatics. She’s now doing her PhD in Edinburgh. I also a supervise a student from Syria who came here as a refugee, whom I identify with a lot. His refugee status was just approved, after what has been a tough time, and he is very excited thinking about all the possibilities in his career. I dedicate a lot of my work time to mentoring, which I deeply enjoy. I hope eventually as I settle in this job, I’ll get a chance to go back to the bench a little bit more.

You were recently awarded the British Society for Parasitology Award. This is a huge honour! Congratulations. Can you tell us a bit more about your work, about this award, and what it means to you?

This is indeed a big honor and one I hold very close to my heart. I knew some colleagues were going to put me forward for this award but didn’t think I had a chance to be selected as I think there are many brilliant emerging parasitologists in the UK now, all of whom are deserving of a recognition like this, so I was extremely surprised when I receive the email from the BSP council. The award was given in recognition of the work I conducted in Glasgow in collaboration with many brilliant mentors (Annette MacLeod, Neil Mabbott), colleagues (Matthew Sinton, David Bending, Lalit Kumar, Emma Briggs, Thomas Otto), and trainees (Praveena Chandrasegaran, Agatha Nabilla, Bachar Cheaib). The BSP also recognized my efforts to change the research culture through my involvement with several initiatives to promote inclusion for LGBTQ+ scientists (The STEM Village) and opportunities for ECRs in Scotland (SPPIRIT network). This award means a lot to me – it validates years of hard work, setbacks, personal sacrifices, and additional challenges when trying to forge a “niche”. I am incredibly grateful to the society and to my colleagues and friends for their support and their endorsement. Moving forward, I plan to pass on all the lessons I learned along the way to the people training in my lab.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Venezuela?

Actually, no, and it’s a real pity. I think our culture and daily life is unique, and it enriches spaces that tend to be “colder”. Of the Latin American research that I have connected with in the UK, I had the chance to work with two scientists from Uruguay who became very dear friends. In Mark Field’s lab I also had two colleagues who were from Cuba, who have both recently been promoted to professor, either in Habana or abroad. In addition to this, I have also interacted with the VeConVen network (https://www.vbdvenezuelanetwork.com) coordinated by Martin Llewellyn and others to raise aware of Chagas disease in endemic foci in Venezuela and other neighboring regions, although so far this interaction has been more to learn about the network rather than being a collaboration so far.

A personal vision I have is to engage more with my own country even though I have chosen to stay living abroad. Many of the alumni from the university where I studied in Venezuela, organize virtual seminars where they teach different things to students in Venezuela. What I would love is to support students who have an interest in immunology, or any of the topics that my lab focuses on, and ultimately to give them opportunities to visit my lab, so that they can learn new things, and be exposed to different cultures. Now, more than ever, it’s important to keep this lifeline open for students who are going through a terribly difficult time in the history of Venezuela, and it’s important to keep them motivated and with a strong and optimistic vision of their prospects for the future.

Who are your scientific role models (both Venezuelan and foreign)?

I was recently discussing this with my husband, and, to be honest, I have found it hard to identify role models as such. During my career, I tried to find someone who looks like me not only “physically”, but also in terms of their career trajectory, so that I could have a sounding board and form a network of support, and I haven’t found any. It’s one of the things that makes me very sad, especially these days. It’s difficult. If I came from a different place, or had a different training or ‘pedigree’ it might be easier. I think if I had to define role models for me, they would be people who have gone through difficult situations and have prevailed. Sometimes there’s a prejudice or notion that role models are more senior people in terms of hierarchy and age, but this notion is not accurate. Younger people who might be early in their careers and have had different life experiences, have lots to teach us all too. We should recognize better that we are part of a community, and that this community should be fostered. I don’t like people who think they are superstars, and that they reached this stardom all on their own. I actually find it deeply disturbing. I always say that I wouldn’t be able to be where I am today, were it not for all the people who gave me a chance and opened their doors to me. While that’s my take on role models, there have been incredibly impactful people in my career. Someone I must mention in particular is Alvaro Acosta Serrano – he has led the way for many of the things that I am doing.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Venezuela, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

Overall, I think in Venezuela the gender disbalance is not as extreme as I have seen in other countries, even in Europe. Latin American society is thought of as being very patriarchal, but it’s actually matriarchal – in my own house, in my university, leadership falls on women. Nevertheless, like in other countries, the highest positions such as Deans of faculty , are still mostly male-dominated. Regarding the impact on my career, I have had the chance to work with many great women leaders. I have spoken a lot with Annette MacLeod for instance, about her experience as a woman in science, especially in previous times, and I use this as an inspiration for myself.

Are there any historical events in Venezuela that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

I think socio-political movements that started in Venezuela towards the end of the 1990s led to a radical change of many things, including how we understand science. If we think about the government’s priorities for funding, for instance, they now prioritize the impact of science on the community, so the focus is no longer on basic science. This changed the dynamics of scientific research. The IVIC (Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Cientificas), which back in the day was a vanguard institute in Latin America because of the basic science done there, today works mostly on applied sciences: agronomy, social sciences, etc. I don’t know if this is a historical event, but it’s a bifurcation in time which changed the direction of science, and re-shaped the scientific landscape of the country entirely.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Venezuela?

In the context of the previous question, any Venezuelan scientist who wants to go back to Venezuela has to figure out how their research fits into the current political agenda and priorities. Otherwise, it’s very difficult to go back. Also, doing research in Venezuela is very challenging compared to many other countries, as it takes a long time to receive items like reagents, and they are eye-wateringly expensive, which is often prohibitive to the research being done. However, on the flip side, this fosters creativity and resourcefulness – you learn how to troubleshoot with the resources you have, and I think that this gives us a great advantage in our training, compared with countries where these challenges don’t exist. I think it’s important to always focus on the positive within the challenges. I think eventually this experience with dealing and working with limited resources, and this resourcefulness and creativity will play an important role as we move towards more sustainable science, for example.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

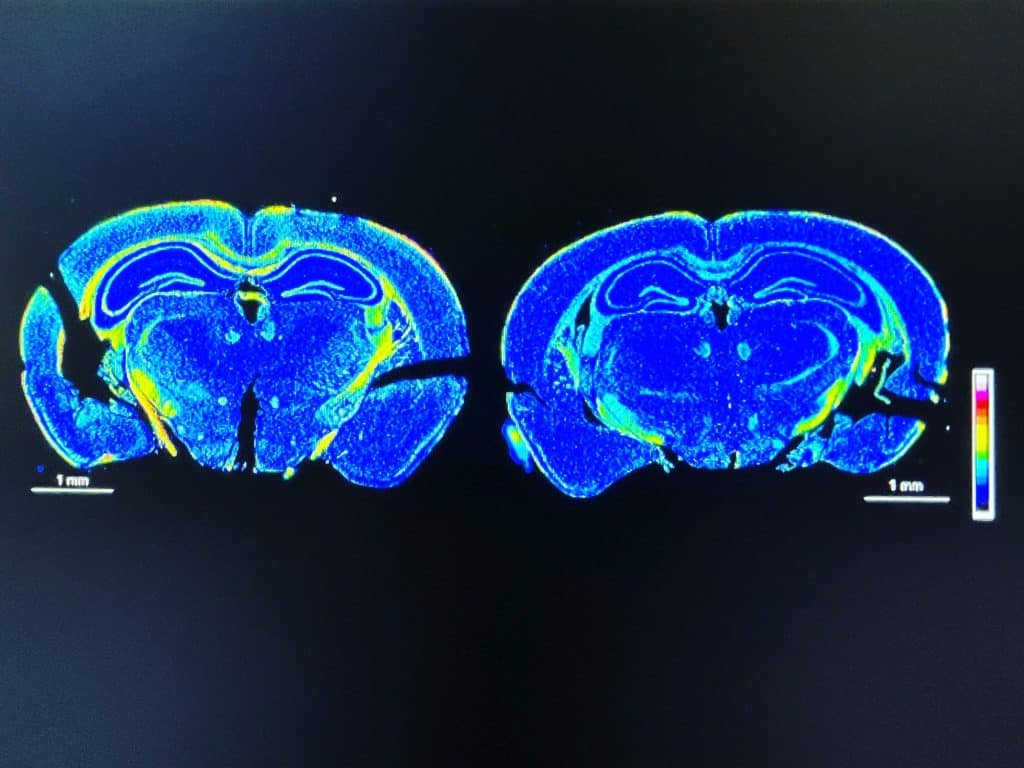

I love all types of microscopy but right now I love mesoscopy, which has the capacity to see through big volumes with a high level of resolution. It’s something revolutionary and totally fascinating. If you ask me a year from now, this might have changed again to something like expansion microscopy!

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? A eureka moment for you?

Can I choose several? I really liked a paper published by Jim Brewer where he used cranial windows to observe leukocyte recruitment during infections. I also liked Gail McConnell’s paper on mesoscopy looking at bacterial colonies and highways for the transport of nutrients – how bacteria in the center of the colony feed, compared to those at the edges. I also love your work on intravital microscopy and trypanosomes! Those are three that I have found particularly extraordinary. Of my own work, I love what I am currently doing, which is investigating immune responses in the brain during Trypanosoma brucei infection, and I feel that my lifespan will not be enough time to address all the scientific questions that have arisen. There are so many questions! I also love seeing that there are fellow scientists who are addressing similar questions to me because this gives research momentum, and it gives us confidence that our work is reproducible. I was recently speaking to a student in Cambridge who was very anxious about his work and people who are doing things similar to what he is doing. I told him we have to change the philosophy and mindset about this in science: if someone in a physical space different to your own reaches the same conclusion as you, it can’t be a bad thing! This is what science is.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Venezuelan scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

My first piece of advice is to trust your instinct. Go ahead, regardless of what people say. If you are passionate about it, pursue it. It’s important that when you go to bed at night, you feel satisfied about the exciting work you are doing as a scientist. Everything else is noise. Learn to focus on what matters about science itself.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Venezuela, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

Being honest, I have always wanted to come back. I have never felt ‘complete’ since I have been away from Venezuela. You learn how to be a different version of yourself when you move abroad, but when I am at home, with my family and friends, is when I feel fulfilled. My vision for the future is a country that is fairer, where people can do the science that they want to do, and where there is space for everybody, regardless of the research area that they focus on. That diversity is appreciated, respected and promoted. That’s the ideal future I want for my country. This is probably not specific for my country though. I’d love for any environment where I am based to recognize and celebrate our differences, as these differences are so important for our creativity. I’d also love to collaborate with scientists in Venezuela. Right now, through the VeConVen network, I have had the chance to connect with medical students in Venezuela and other Latin American countries who work on Chagas disease. I think this group of students is amazing and I would love to collaborate with them, see them grow, and help in whatever way I can.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Venezuela a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

The people! Any foreigner coming to Venezuela, always feel at home. We make people feel like they belong, and this is not something I have found in many of the places where I have lived outside of my home country. Venezuelans immediately make you feel as though you are part of their community , and this is so unique. Of course, the weather is amazing, and the wealth of ecosystems and their beauty are breathtaking – we have everything from beaches to snow! If you ever have the opportunity to visit, you totally should – you won’t regret it!

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)