A journey of a novice in immunofluorescence assay

Posted by Seth Domfeh, on 15 November 2024

I am Seth Domfeh, a lecturer and an early-career researcher from the Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana. I am delighted to share my experience before and during my research visit to the Africa Microscopy Initiative (AMI) Imaging Centre, Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine, University of Cape Town, South Africa. I am a trained medical laboratory scientist and was exposed to microscopy earlier in my career to diagnose malaria and other infectious diseases in a hospital setting. However, with further training in immunology and molecular cell biology, I became fascinated with the cellular localisation of proteins, leading to my interest in fluorescence microscopy.

In October 2022, I had the opportunity to attend the Imaging Africa Workshop organised at the AMI Imaging Centre, which exposed me to the benefits of microscopy to my research. In the workshop, we covered sample preparation and how to use the microscope as a quantitative tool. Although I recognised the benefit of these techniques for my research, I had limited hands-on experience in sample preparation for fluorescence microscopy, so I began looking for another opportunity to acquire expertise in immunofluorescence assays. Fortunately for me, in March 2023, the first call of the AMI Visiting Researcher Program was launched. I was thrilled to receive a confirmatory email that my application for this prestigious award was accepted and that I would be able to test my hypothesis in Africa and acquire experience in bioimaging experiments.

Moreover, I received another email from Dr Michael Reiche, the AMI Imaging Centre Operations Manager, in August 2023, saying that AMI will be hosting a roundtable discussion at the Gates Grand Challenges Annual Meeting in Dakar, Senegal, in October 2023. To my amazement, I was invited to join the panel to give a five-minute presentation on my project, which gave me more confidence as an early-career researcher from Africa. In Dakar, I had the opportunity to build collaborations with other scientists, including Dr Jerolen Naidoo (Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, South Africa), who has experience generating primary human hepatocytes from Africans and using three-dimensional cell culture models, which are imperative in my future research.

In November 2023, the planning of my visit to the AMI Imaging Centre started with getting the appropriate consumables and reagents ready for my experiments. I am grateful to the AMI team, led by Dr Reiche, for ensuring the seamless visit from 03 July to 03 August 2024. I had two goals for the visit: (1) to acquire expertise in immunofluorescence assay and (2) to test my hypothesis. High blood glucose has been reported to suppress the type 1 interferon response, an innate immune response pathway that prevents infections and cancers. The nuclear translocations of two complexes are crucial in interferon production (IRF3-IRF3) and response (STAT1-STAT2-IRF9); hence, it was hypothesised that high glucose prevents the nuclear localisation of these complexes. I had this concept, but my idea would have been on the shelf without the AMI Imaging Centre since I could not access resources or a confocal microscope, which were required for me to test the hypothesis and acquire hands-on experience. Also, I was privileged to be supported by The Company of Biologists through the Journal of Cell Science’s Travelling Fellowship to execute the proposed experiments at the AMI Imaging Centre.

On 03 July 2024, I arrived in South Africa with the enthusiasm to test the hypothesis. However, at the AMI Imaging Centre on 04 July 2024, I realised that the four-week visit period was insufficient to execute all my experiments; therefore, with support from the AMI team, I decided to investigate the effect of high glucose on the nuclear localisation of the STAT1-STAT2-IRF9 complex and acquire hands-on expertise in immunofluorescence assay. Generally, the four-week visit was a roller-coaster experience, with the cell lines for the experiments becoming my first hurdle to cross. Since I wanted to test the effect of high glucose levels on an immune response pathway, I planned to use human monocytes (THP1 cells), which are immunologically competent, for the experiments. Also, I planned to repeat the experiments using human hepatoma (HepG2) cells as surrogates for hepatocytes since the liver is involved in glucose metabolism. However, I could not access THP1 and HepG2 cells within the first week to start optimisation experiments. Human embryonic kidney (HEK293T) cells were already growing in the laboratory, and I thought it was an excellent opportunity to use them to optimise antibody concentrations.

However, there were no positive results after performing two consecutive optimisation experiments. I became confused and apprehensive; hence, I read about the HEK293T cells and realised that the HEK293T cells are modified to express viral oncogenes, which dampen intracellular innate responses. In my reading, I found out that the parental HEK293 cells are transformed by introducing human adenovirus 5 (hAd5) DNA and further modified by stable expression of the large T-antigen (TAg) of simian virus 40 (SV40) to generate HEK293T cells; the TAg and adenovirus E1A expressed in the HEK293T cells inhibit antiviral responses by interfering with interferon-dependent transcription downstream of nucleic acid sensor activation. Although I could not optimise the antibodies with the HEK293T cells, this was a valuable lesson that not all cell lines are appropriate for an experimental design. Interestingly, this unexpected experience allowed me to understand that HEK293 and HEK29T cells could not be swapped in experiments because I used THP1, HepG2 and HEK293 cells previously to study the type 1 interferon pathway (https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8873536) but not HEK293T cells.

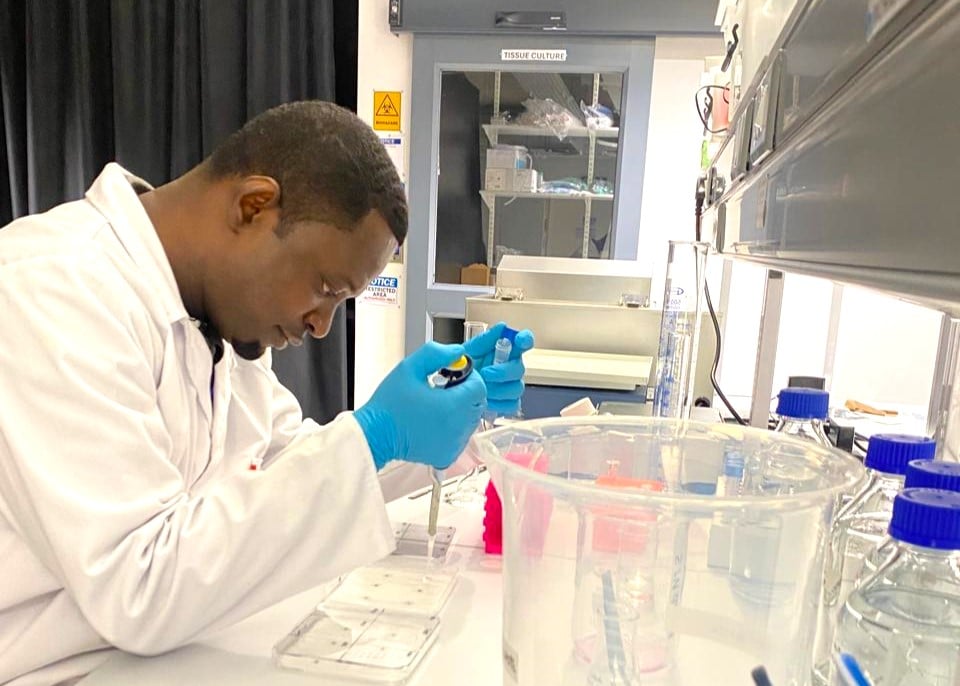

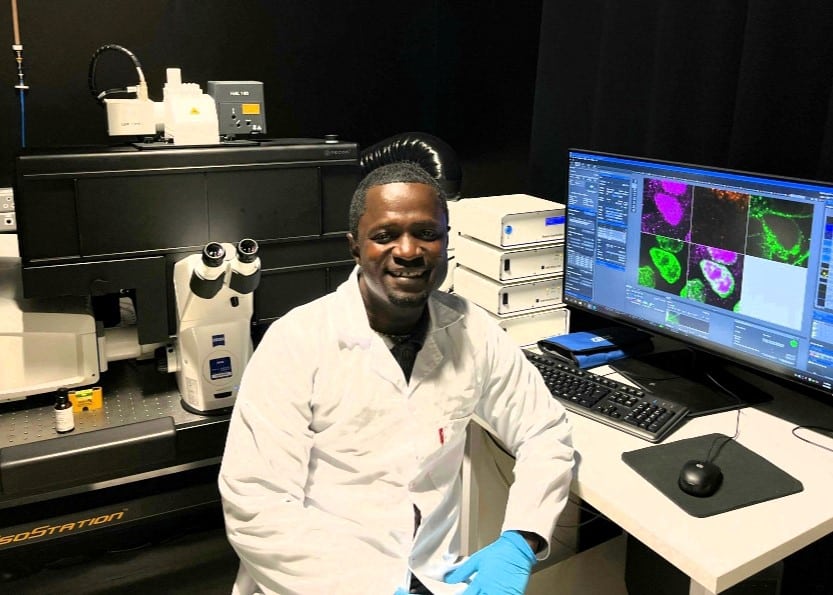

In week two, the HepG2 cells were ready for the optimisation experiments. After some troubleshooting, I was able to validate the antibodies’ concentrations. Within the middle of week three, I started the main experiments by stimulating the type 1 interferon response pathway with recombinant human interferons in the presence of glucose in the HepG2 cells. However, I did not have the chance to use the THP1 cells (which were slow-growing). Interestingly, manoeuvring with forceps to pick twelve 12 mm glass coverslips thirteen times per experiment without breaking any within eight hours of sample preparation was an incredible experience for a novice in immunofluorescence assay. All my hard work was finally rewarded when I acquired my first image showing the nuclear localisation of IRF9 using the Zeiss LSM 980 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope.

Furthermore, I was privileged to be selected to participate in the openScopes Africa in-person workshop from 15-17 July 2024 at AMI Imaging Centre during my visit. I simultaneously attended the workshop, which brought imaging enthusiasts from Africa and performed my experiments. The workshop was worth participating in because it exposed me to low-cost, open-source microscopy hardware and software enabling researchers to access advanced imaging techniques by assembling our affordable, configurable, locally sustainable and upgradeable research-grade microscopes. During the workshop, I could build a fluorescence microscope from scratch. This workshop also helped me meet other early-career researchers from Africa who are interested in bioimaging for collaborative research. Besides, I entered the Africa BioImaging Consortium imaging competition with one of the microscopy images from my experiments showing the nuclear localisation of IRF9 in interferon-stimulated HepG2 cells, and I won the second prize (https://www.linkedin.com/posts/seth-domfeh). However, I have yet to analyse the images acquired for patterns to develop a manuscript for a potential submission to the Journal of Cell Science. I am still a newcomer learning how to use image analysis software.

My primary goal of acquiring expertise in immunofluorescence assay was achieved during the visit, developing skills for my research career. I am grateful to the AMI Imaging Centre and The Company of Biology for sponsoring my visit. Special thanks to the AMI team: Dr Michael Reiche, Dr Viantha Naidoo and Dr Silindile Ngcobo.

(3 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

(3 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

Thank you for sharing this inspiring journey and the lessons learnt. Indeed, every challenge is a blessing in disguise. Congratulations, Dr. Domfeh.

Congratulations, Dr. Domfeh. Thank you for sharing this inspirational yet challenging and rewarding experience!

What a beautiful way of narrating a rocky but successful research journey. Very inspiring and beautiful realistic. Congratulations and good luck in future and endeavors 🥳

This was very informative and inspiring. It captures both struggles and success in research work. Congratulations, Dr. Domfeh 🥳

Amazing. This is truly inspiring. Nothing good comes on a silver platter. Hardwork pays. Congratulations Dr. Seth Domfeh. This is worth emulating.

Wow really inspiring and insightful 🎊🎊🙏🏾. Congratulations Dr. Domfeh 🎊. I wish you more great achievements 🎉

Remarkable. Thanks for sharing Dr. Domfeh. Indeed this is an inspiring story to encourage all researchers. You are an inspiration and an asset to the Ghanaian research community. Congratulations.

Good job Seth. This is beautiful!

“I am still a newcomer learning how to use imaging analysis software” is a hard statement to believe given the depth of knowledge and mastery displayed in this article. Congratulations, Dr. Domfeh.

Thank you Dr Domfeh, this article is a testament that, challenges are meant to strengthen and push us to heights we can’t imagine. Reading it has encouraged me a lot.