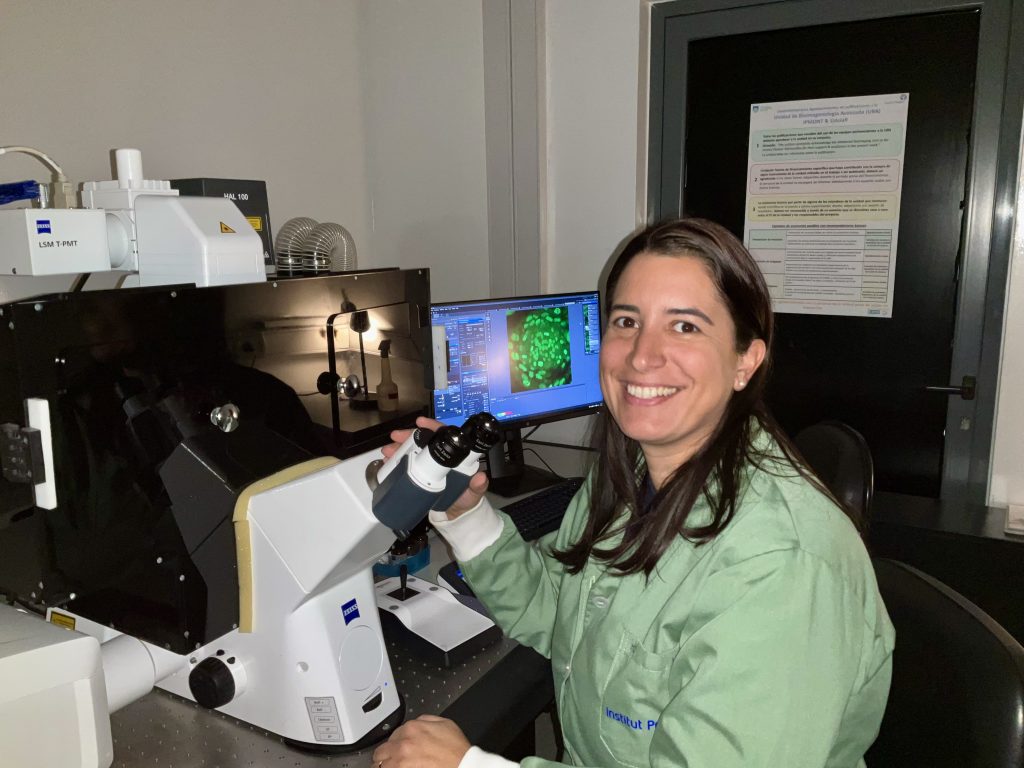

An interview with Marcela Diaz

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 21 June 2022

MiniBio: Marcela Diaz is a co-leader of a Chan Zuckerberg Initiative project at the Advanced Bioimaging Unit (a joint Unit between Institut Pasteur de Montevideo and the Faculty of Medicine of Universidad de la República, Udelar). With this grant, her aim is to generate a program to train imaging educators, and in this way promote knowledge exchange between multiple communities (consistent with the democratization of science). She studied a degree in biological sciences at the Faculty of Sciences of the Udelar. Her undergraduate thesis and her master’s thesis in neurosciences were carried out in the Department of Neurochemistry at the Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas Clemente Estable, where she began her training as a microscopist. She has over a decade of experience as a member of Imaging Core facilities, and has vast expertise in various imaging modalities. Her academic research focuses on neuroscience, however, she has dedicated an important part of her career to providing service to users.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I always liked Biology, animals and the sea. I feel it was a vocation. My first ‘dream’ was to become a Vet. But when I reached the 5th year of high school, when we started studying Biology, we had a practical that I remember like it was yesterday: we used a light microscope to see living microorganisms, and it was an eureka moment for me – it became clear at that moment that I wanted to become a scientist. Here I started inquiring about career possibilities – I knew I didn’t want to become a medical doctor, but I wasn’t too sure what else was possible. And then I found out about the Faculty of Science. In my 6th year of high school, my mother had an acquaintance who worked at the Faculty of Science, in Marine Biology, and she took me there for a visit. Although I loved Marine Biology, another thing I found fascinating was Neuroscience, and to understand how the brain works. So when I reached the last year of my Bachelors degree – which is when we choose optional subjects based on our interests- I chose Neurosciences. I find the brain fascinating – despite all the research done on this organ, we still know relatively little on how exactly it works.

You have a career-long involvement in microscopy and neuroscience. What inspired you to choose this career path?

Since I started my thesis for the Bachelors, I started working at the Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas Clemente Estable, which is an institute pioneer for microscopy here in Uruguay. Already at this time I used fluorescence microscopy as a tool for my work, and I loved it from the beginning. When I was finishing my Bachelors and about to begin my Masters in Neuroscience, a job became available to join the Institute as a technician for the Microscopy Unit at the Instituto Clemente Estable. I was there for 7 years, and in parallel doing my MSc in Neuroscience. When I finished my Masters degree, a call opened to join Institut Pasteur de Montevideo, also in the Microscopy Unit, and I accepted this offer. Around this time I paused my academic research, and dedicated myself to user service for microscopy. I’ve been here for 8 years now. Only recently I started my PhD. This was because in 2020, Dr. Leonel Malacrida (the head of the Unit for Microscopy and Advanced Bioimaging) brought a new concept to the unit: to not only use commercially available microscopes, but to develop new tools and new methods. He offered me the chance to do a PhD under his supervision, where I can integrate my interest in Neurosciences and at the same time develop and implement new methods of microscopy. I am truly interested in the technical career within a core facility, but in order to advance further, I think a PhD will be advantageous, so this is a great opportunity.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Uruguay, from your education years?

I think our education system is very good, and it is great at forming scientists. I think because we don’t have a huge amount of resources, we are trained to be resourceful. This is something relatively common in Latin America. Beyond the education years, the fact that the scientific community is relatively small, we have strong networks of collaboration. This facilitates work a lot. I think this is an advantage we have in Uruguay.

Can you tell us a bit how is your day-to-day life working at a Microscopy core facility?

What I love about working in a core facility is that every day I learn new things. The scientific community in Uruguay is relatively small, so it’s relatively easy to know one another and what other people are doing in terms of research. All these years of experience have allowed me to network with multiple researchers, and link their work to the various projects and ideas. The knowledge and techniques are many times interchangeable. Sometimes I can suggest new ideas for the various projects due to linking these experiences from the various projects. I help users with sample preparation, imaging, image processing and I’m currently participating in various collaborations. At the same time I’m starting to work on my PhD project. It’s a busy time 🙂 Also, we are not so many in the Bioimaging Unit, so I have multiple responsibilities. I am very busy but very happy with the work I do!

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Uruguay?

Within Uruguay we have strong collaborations, but with the rest of Latin America I haven’t had a lot of chances for collaborations. I believe though, that the formation of Latin American Bioimaging is aiming to change this and foster these international collaborations in the region. But this is only starting – I think it is very promising. I think this will be good also to get know-how from how different facilities work in the different countries. For instance, I know that in Argentina they have a very well organized network for resource availability that allows them to a) know which microscopes are available in the country across different institutions, and b) be able to book them and use them as required. We still don’t have such a system. It would be great if such a system existed across countries in the Latin American region. Within Uruguay I feel it’s a small country and this facilitates interactions. Many important institutes are centralized in Montevideo, and particularly in a specific road called Avenida Italia – so we are all relatively nearby. Everything is within a 10-40 minute reach. We can come with samples by car or bus to the different institutes.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Uruguayan researcher, working abroad?

Unfortunately, what I feel is missing for imaging technicians, is precisely opportunities to train abroad. There is relatively little funding, and almost no choices if you’re not a student. We are sort of outsiders. Nowadays there is a little bit more of inclusion. Perhaps in the future I have access to more opportunities – also now as a PhD student. But this is something common for microscopy technicians.

You are currently a coordinator for a CZI imaging grant. Can you tell us a bit about your work respective to this?

Dr. Leonel Malacrida told me about the opportunities by CZI and encouraged me to apply to the grant. We just started now with the coordination of this project, but I am very excited about it: one of its proposals is to train educators, using multiple virtual technologies. We have bought new equipment for videoconferencing to be able to exponentially expand knowledge in microscopy across a vast number of communities through the technicians in core facilities.

Who are your scientific role models (both Uruguayan and foreign)?

Without a doubt, Leonel Malacrida. He has been a great leader – he is inclusive, and has given me many opportunities for growth as a scientist and as a member of the core facility. I really look up to him.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Uruguay, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

The Institut Pasteur de Montevideo recently had significant policies and activities to improve gender balance. The idea is that everyone having the same position should earn the same salary. Equally, they aim to balance the positions held, with one’s experience. For instance, the job I was doing was rendered as being superior to the position I held and so I got a promotion. Now there is a better perspective for both, scientists and technicians, to be able to grow within the institute. This was not always the case for technicians. We were being left behind/outside, and now we have better support and better opportunities for our future. Regarding my role in specific, I believe some women in Uruguay are members of Microscopy core facilities. But in the Advanced Bioimaging Unit at the Institut Pasteur we are 4 technicians and researchers, and I am the only woman.

I am also the mother of two young children – I feel that the plans for gender equity have been very beneficial for women who are mothers: they take into account career breaks due to maternity leave and parental duties.

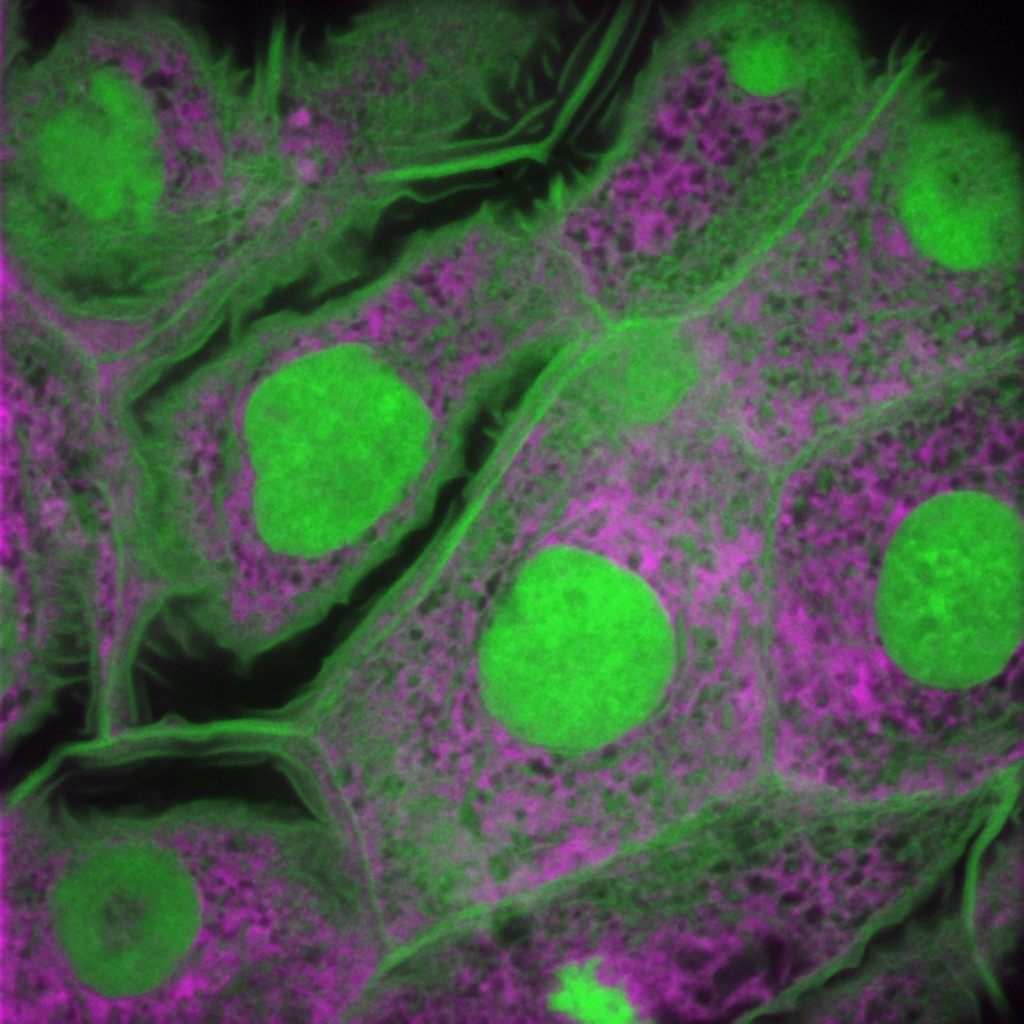

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

Optical microscopy, especially fluorescence microscopy, is my favourite. I love confocal microscopy in particular. I feel it’s relatively easy to master, it can be applied to pretty much any project, and it gives answers to many questions. Super-resolution is nice too, but it’s much more specific. Confocal microscopy is much more versatile. In addition it’s beautiful – it appeals to my inner artist too. In fact in my house I have framed some microscopy images and put them up on the walls as decoration Beyond this, in Uruguay we are currently building a two-photon microscope and a Diver microscope to be able to image deeper in tissues than a classic two-photon microscope. I am getting to see how a microscope is built from scratch! It’s a lot of fun, but it’s not so easy.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

I’ve had many many many 🙂 as I collaborate with many users, we have had celebrations with hugs, excited shouting, jumping and so on. It’s very rewarding to be able to help users, and see things working well. One of the most exciting experiences I can remember was when a Professor that had been my teacher at the Faculty of Sciences came to the microscope with what seemed un-used slides. I thought ‘why is he looking at clean slides?’, and he told me he was studying the spiderweb of a spider that ejects its web from its legs, unlike most spiders, which eject the web from their abdomen. Like Spiderman 🙂 So he would make these spiders walk on the coverslips and then we were looking at their webs through the microscope. I found this extraordinary. I really have learned a lot through the years.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Uruguayan scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

I think the main piece of advice is that as a microscopist you cannot just watch, you have to observe with attention and care. Don’t just do imaging focused on the one question you want to answer: there are many other things in an image that might be extremely relevant, beyond the original question. It has happened to me through my career, that a ‘peripheral’ observation ended up being an important discovery. Sometimes scientists don’t see this or think it’s an artefact. With all my years of experience, I feel now I see a lot of things in images. So my advice is see beyond your question and don’t discard anything as ‘irrelevant’ or ‘unimportant’.

When students have asked me how to follow a career to become a member of a core facility, unfortunately in Uruguay we don’t have a track to become so. In other countries this option exists, but not here yet. But if you do follow this path, perhaps it’s important to travel. I just came back now from a visit to Mexico, and I was able to see many things they do differently in their facilities, and I feel I’ve learned a lot to bring this know-how to our unit.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Uruguay, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I feel the work that Dr. Leonel Malacrida is triggering will be huge for our country. Bringing new technology to the country will allow us to answer questions that we previously couldn’t. Being able to build our own microscopes is huge because we can stop depending on commercially available microscopes which sometimes are unaffordable or the maintenance is complicated- within a few years these microscopes become obsolete and service is no longer provided. If we don’t have human resources with expertise to fix them, it’s complicated. Also, the huge companies producing these microscopes don’t provide enough information that would allow someone external to maintain and fix the microscopes. This is limiting. So I see that this concept of building our own equipment has huge potential for our country. 3D printing is also being used to create microscope parts for low-cost replacement. Equally, as part of the UruMex collaboration (with Mexico), there are projects ongoing to create 3D printed microscopes for schools to promote microscopy from an early age. This in addition has allowed us to engage with the non-scientific community. I am very happy to be part of these initiatives, and hopefully contribute to a better future for microscopy in Uruguay.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Uruguay a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

From the science point of view, the fact that we are relatively few, favors the scientific interactions and networking. Moreover, Uruguay is a safe country – it has a good life quality. Distances are very short compared to other mega-cities in Latin America, and this optimizes commute, work, and leisure time.

(2 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

(2 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)