Cytoneme Imaging Tips and Tricks

Posted by Christina Daly, on 19 January 2026

There has been a growing interest in visualizing long and thin membrane extensions. The field of intercellular connections has exploded, with elegant bioimaging studies focusing on structures like cytonemes, tunneling nanotubes (TNTs), intercellular/cytokinetic bridges (IB/CBs), and migrasomes. This enhanced interest in the intercellular communication facilitated by these extensions is largely due to the recent technological advances in imaging approaches. As a postdoc in Stacey Ogden’s lab at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, my research focuses on Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) ligand transport along cytonemes. These specialized cellular protrusions function as signaling filopodia that facilitate transport of morphogenic and growth factor ligands and receptors, primarily during development and in stem cell niches. Our lab has optimized protocols for visualization of these extensions, both in cultured cells and in murine embryos. Every time I present my work, scientists approach me to help identify intriguing extensions from their own microscopy. With the growing interest in the field of intercellular connectivity, it’s a timely moment to discuss our extension preservation protocols and offer some tips and tricks to discriminating between extension types.

Imaging Cytonemes in Cultured Cells

Bodeen WJ, Marada S, Truong A, Ogden SK. A fixation method to preserve cultured cell cytonemes facilitates mechanistic interrogation of morphogen transport. Development. 2017 Oct 1;144(19):3612-3624. doi: 10.1242/dev.152736. Epub 2017 Aug 21. PMID: 28827391; PMCID: PMC5665483.

Hall ET, Ogden SK. Preserve Cultured Cell Cytonemes through a Modified Electron Microscopy Fixation. Bio Protoc. 2018 Jul 5;8(13):e2898. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2898. PMID: 30906805; PMCID: PMC6426145.

Tip one – prepare fresh buffers and add/remove them gently

The prevalence of cytonemes was historically unappreciated, because these long, thin filopodial structures are very fragile and do not survive conventional cell fixation methods. To enable mechanistic study of cytoneme biology, our lab developed a Modified Electron Microscopy fixation (MEM-fix) protocol, which uses a 0.5% glutaraldehyde/4% paraformaldehyde solution for enhanced crosslinking to achieve greater stability of thin extensions during immunofluorescence processing (protocol detailed in Hall and Ogden, 2018). This protocol includes a glutaraldehyde quenching step, with 1mg/mL sodium borohydride (NaBH4) added to the blocking/permeabilization buffer. This quench/block solution should be made fresh, just before use, so I recommend preparing it during the post-fixation washing steps. The sooner that NaBH4 treatment is applied, the better the quenching, so shortening wash times between fixation and block/permeabilization can alleviate glutaraldehyde autofluorescence. Another important aspect of protecting extensions during sample processing is by pipetting/aspirating slowly and gently to exchange buffers and avoiding rocking or disturbing the cells.

Tip two – use membrane markers to visualize cytonemes

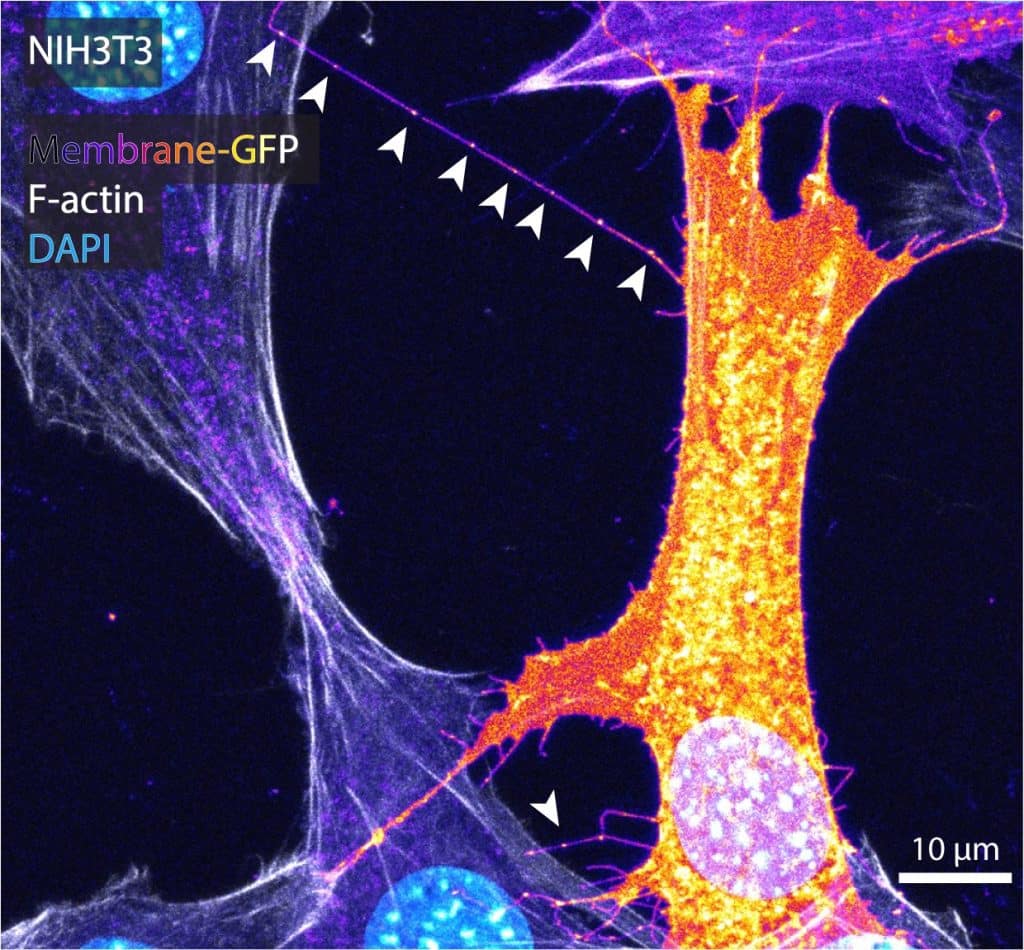

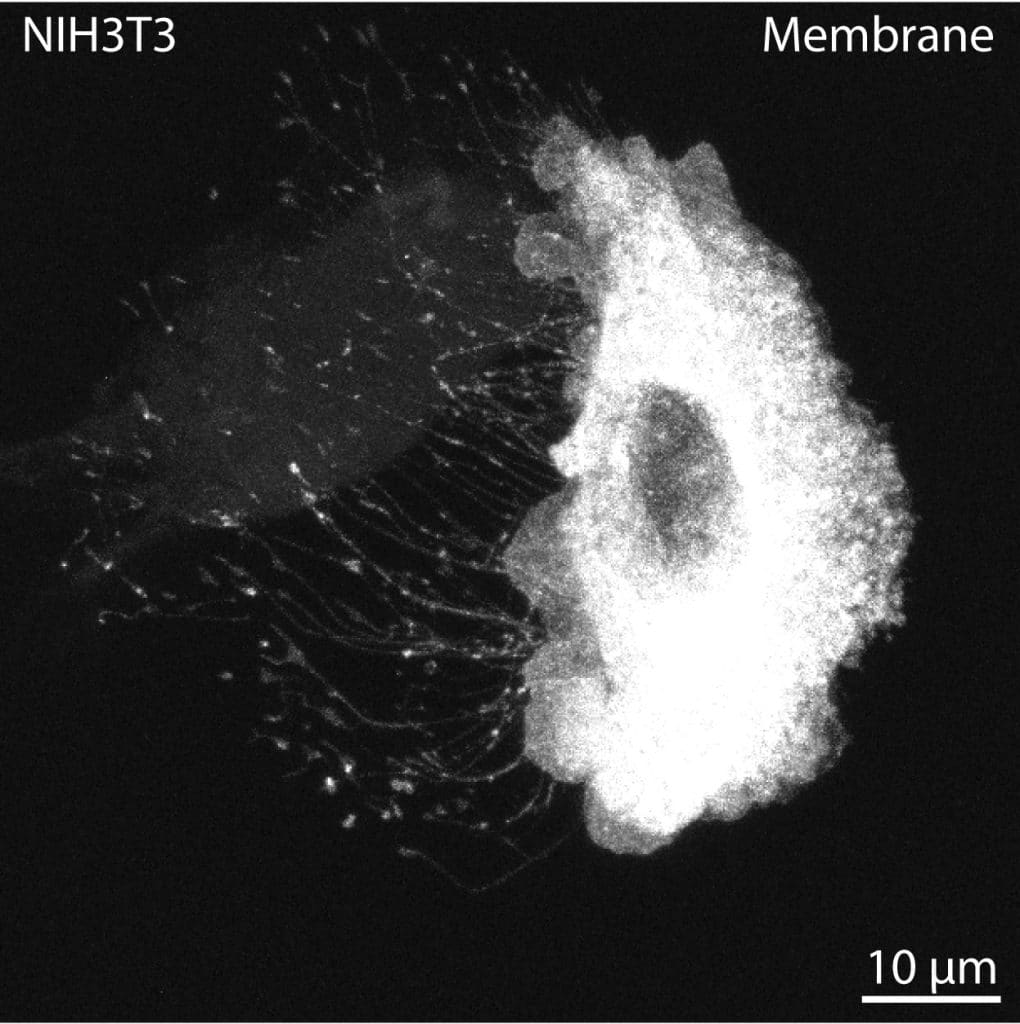

While MEM-fix effectively preserves cytonemes, it also maintains other extension types such as tunneling nanotubes (TNTs), retraction fibers (RFs), and intercellular/cytokinetic bridges (IB/CBs). Unfortunately, to date, there are no specific markers for cytonemes. The best way to distinguish cytonemes from similar structures is their morphology and the presence of morphogen/growth factor ligand and/or receptor cargo. To image cytonemes, actin stains like phalloidin are rarely sufficient. Cytonemes are incredibly thin, so while dependent on actin, the thin filaments are usually undetectable through conventional high-resolution microscopy. Therefore, the best way to label cytonemes is through membrane markers, such as transfection of a membrane-tethered fluorophore or staining using commercially available plasma membrane stains like Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA) conjugates (Image 1).

Tip three – adjust your focus away from the coverslip

In cultured cells, cytonemes normally originate from areas on the cell situated away from the basal-most, coverslip-contacting surface. Therefore, adjusting Z focus away from the coverslip can enable discrimination of filopodial-like extensions from coverslip-adhered retraction fibers.

Tip four – looks for structures >10micron

Cytonemes can be short, but they often grow to lengths of 10-50 microns in cultured cells. Therefore, I impose a ³10 micron length restriction when quantifying extension prevalence to eliminate conventional filopodia. Additionally, cytoneme cargo can be transported in intracellular vesicles, often resulting in a beads-on-a-string appearance along cytoneme lengths, particularly post-fixation (Image 1, arrowheads). The beads-on-a-string appearance is shared by RFs, as they collect intraluminal vesicles for migrasome formation. However, RFs are adhered to the coverslip on the trailing edge of the cell.

Tip five – aim for cell confluency of ~60-70%

Cytonemes often appear on the leading edge or ruffled periphery of cells, and will adhere to neighboring cell surfaces, if possible (image 1). Thus, a final cell confluency of ~60-70% is optimal, allowing distance for cytoneme outgrowth while permitting docking on nearby cells for cytoneme stability.

Tip six – look primarily for curved or angled, close ended structures

Cytonemes are more likely to be curved or angled as compared to straight TNTs and IB/CBs. TNTs and IB/CBs often contain microtubules, which can render them thicker (some ³700 nm) in appearance than cytonemes, which are only ~200nm in diameter. Cytonemes remain close-ended, therefore the intracellular contacts are discrete, and cell membrane or cytoplasmic markers remain segregated (image 1). TNTs and IB/CBs are generally open-ended, facilitating homogeneity of intracellular contents between the connected cells.

Imaging Cytonemes in Mammalian Tissues

Hall ET, Daly CA, Zhang Y, Dillard ME, Ogden SK. Fixation of Embryonic Mouse Tissue for Cytoneme Analysis. J Vis Exp. 2022 Jun 16;(184):10.3791/64100. doi: 10.3791/64100. PMID: 35786607; PMCID: PMC9590306.

Hall ET, Dillard ME, Cleverdon ER, Zhang Y, Daly CA, Ansari SS, Wakefield R, Stewart DP, Pruett-Miller SM, Lavado A, Carisey AF, Johnson A, Wang YD, Selner E, Tanes M, Ryu YS, Robinson CG, Steinberg J, Ogden SK. Cytoneme signaling provides essential contributions to mammalian tissue patterning. Cell. 2024 Jan 18;187(2):276-293.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.12.003. Epub 2024 Jan 2. PMID: 38171360; PMCID: PMC10842732.

Tip one – section using a vibratome

Although MEM-fix is highly effective for stabilization of cytonemes on cultured cells, our efforts to use this formulation on tissue sections were less successful. Thus, we opted for a different approach, sectioning conventionally-fixed tissues (4% paraformaldehyde) on the vibratome (protocol detailed in Hall et al., 2022). Vibratome use avoids freezing or other embedding protocols that could damage delicate extensions like cytonemes. Sectioning tissues at 100-200 micron thickness retains native tissue architecture within the sections while allowing the samples to remain optically accessible using a standard confocal microscope.

Tip two – choose your markers carefully

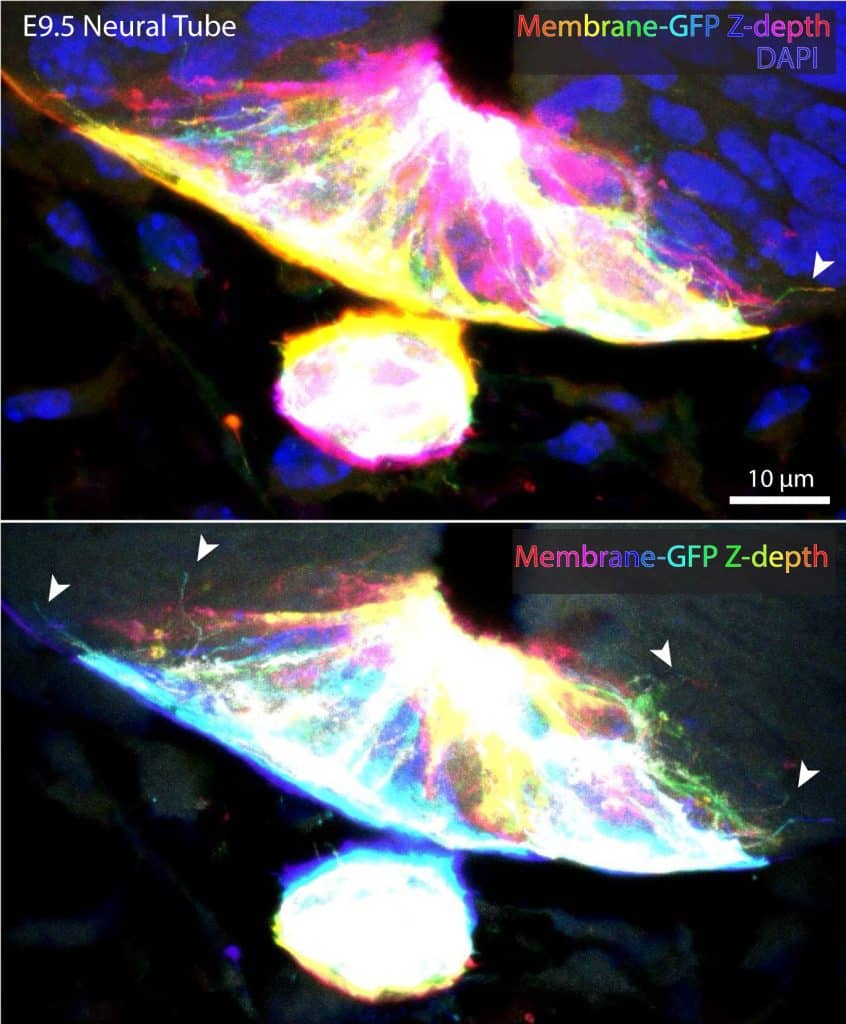

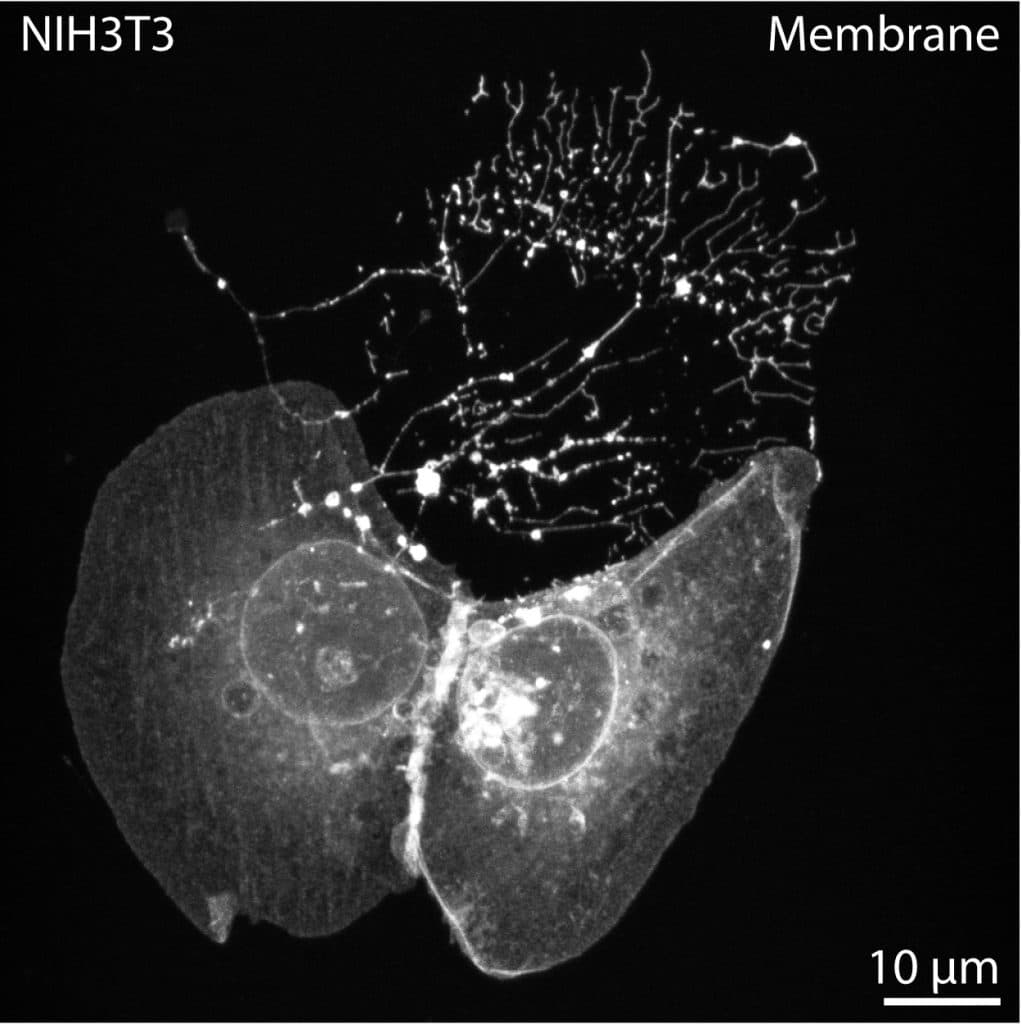

It is difficult to easily discriminate individual extensions in densely-packed tissues using plasma membrane or actin stains. Therefore, tissue preparation is critical, and likely dependent on the experimental questions you are trying to address. For example, our lab relies on membrane-labeling mosaicism through use of Shh-Cre;Rosa26membrane-Tomato/membrane-GFP (mTmG), which selectively labels Shh-expressing cell membranes with GFP (image 2).

The membrane labeling of more restricted subsets of cells permits visualization of thin extensions navigating through tissue and between unlabeled cells. However, while the membrane-GFP stays relatively bright and stable during confocal acquisition, the membrane-Tomato tends to photobleach rapidly. Therefore, I often add DAPI and/or an actin stain to highlight tissue architecture.

Tip three – use a plastic transfer pipette to move sections

Our published protocol outlines an approach for whole-embryo staining of tissues, allowing minimal tissue processing. Depending on your personal research objective, tissue can also be fixed and/or stained post-sectioning. However, post-sectioning staining can be more tedious. For this technique, I rely on plastic transfer pipettes to carefully remove solutions in a controlled manner while visualizing the sections using a stereoscope. I can easily move small sections or tissues around using a transfer pipette with the tip cut off to generate a larger opening. I find this approach more gentle on tissues than using a perforated spoon or forceps. We have been able to confirm cytoneme identity in embryonic tissue due to the presence of SHH ligand cargo in long, thin filopodial extensions (See Hall et al., 2024). These often emanate from signaling tissue, remain close-ended, and are rarely perfectly straight (Image 2).

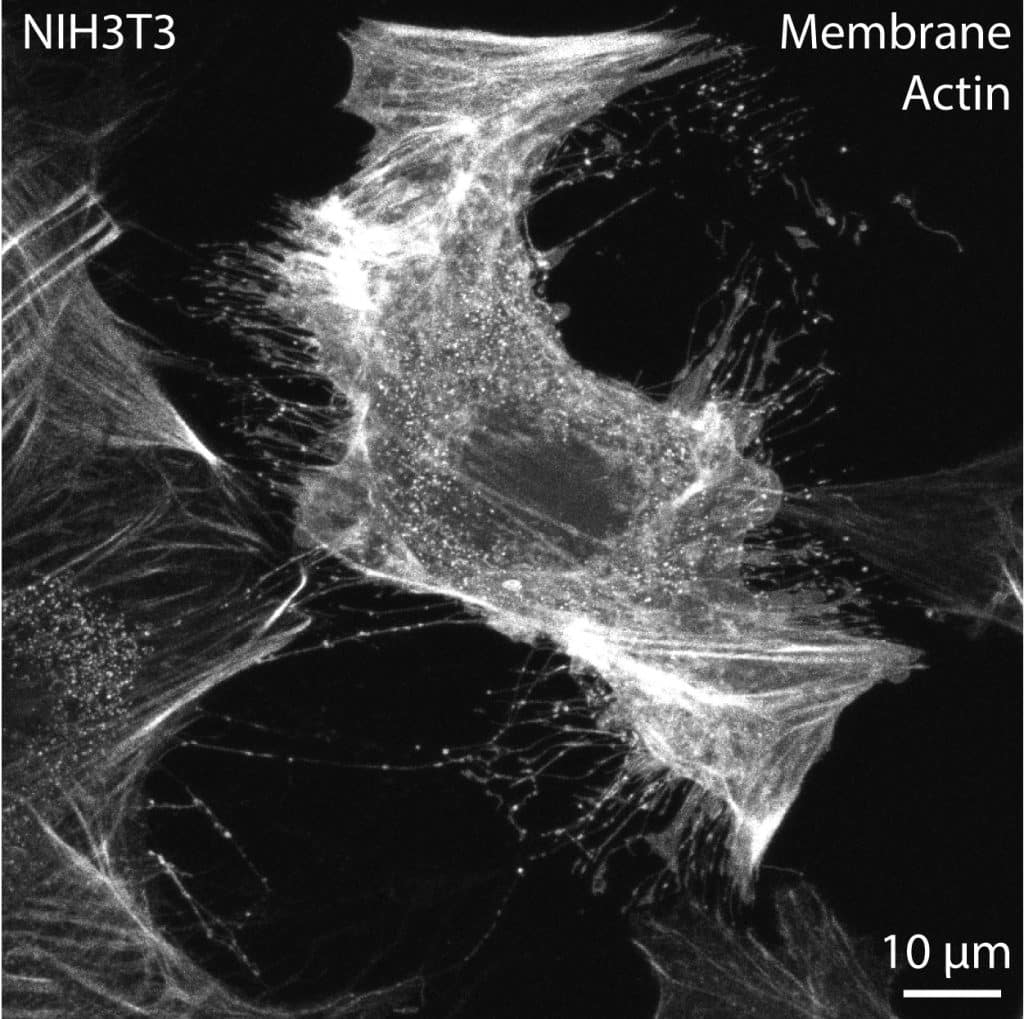

Important Note on Cell Morphology – check for stressed or apoptotic cells

In both cultured cells and tissues, stressed or apoptotic cells are common. These unhealthy cells often project numerous extensions, likely through sustained focal adhesions and stress fibers. These projections are usually thicker than cytonemes, pulling the membrane out from the extension base rather than protruding in a controlled manner (Image 3). These cells should be avoided, particularly for quantification and imaging purposes. I recommend that early cytoneme researchers run a quick live imaging session to calibrate their eyes to stressed cells (Image 3), dying cells (Image 4), RFs trailing behind migrating cells (Image 5), IB/CBs left behind following cytokinesis, or thick, stable, open-ended TNTs that permit cytoplasmic and membrane mixing. Short imaging periods of only 15-30 minutes can reveal extension dynamics and cellular behavior in a way that enables researchers to apply understanding and identification of these cellular processes to fixed cells and tissues.

(1 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

(1 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)