An interview with Marco Andrés Romero Carvajal

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 4 July 2023

MiniBio: Dr. Andrés Romero-Carvajal is a group leader and principal investigator at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, where his lab focuses on Developmental Biology and Regeneration using different models like poison frogs, zebrafish and planaria. He studied his undergraduate degree at the same University, under the supervision of Prof. Emeritus Eugenia del Pino, from whom he first came in contact with microscopy. Inspired by a workshop on Developmental Biology in Argentina, he applied to and was accepted to do a PhD at the University of Utah, and then at the Stowers Institute in Kansas City, in the lab of Dr. Tatjana Piotrowski. In 2015, immediately after finishing his PhD, he was offered a professor position at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, which he accepted. He has led his own research line for 8 years, during which he has aimed at generating interest in Developmental Biology and microscopy among the younger generation of scientists, training undergrads in Cellular and Molecular Biology, and fostering collaborations within the country and the region.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

It’s difficult to pick a single point in time. When I was a child I don’t know if I was excited about science or that I would remember all the dinosaurs’ names, but both my parents are medical doctors. I feel that because of their profession, I was always immersed in the type of work they were doing, the types of equipment they were using, and the discussions they would have. I think being in this environment influenced what I wanted to become. However, later in high school I realized that I didn’t want to deal with human suffering, and so I decided that Medicine wasn’t for me. But I was interested in knowing the mechanisms of how life works. I didn’t know about a specific career that would allow me to focus on this at the time, so I chose Biology by serendipity rather.

You have a career-long involvement in biology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

I also focused on Microscopy by serendipity. During my undergraduate in Biology, the first year or so was very general and I felt a bit disillusioned. But later, slowly, we started looking into Cell Biology, and I realized I loved this topic. I was also looking for a lab in which I could do a practical – the current lab where I am used to be led by Dr. Eugenia del Pino, one of the most important investigators in the country because of her contributions to science. She’s a member of the American Science Academy and other similar organizations. I was walking in the corridor near her lab, and by chance a friend of mine told me that they were looking for an intern in her lab. I had no clue who she was, but Dr. del Pino invited me to her lab for an interview together with her entire team. They all started to make me Biology questions, like a test, and I think I knew some of the answers, but definitely not all. They decided that maybe I was a good fit, and so I joined her lab, first as an intern. I then did my undergraduate thesis there too. I then did my PhD abroad – I was accepted at the University of Utah and did some lab rotations there – the lab I liked most was Tatjana Piotrowski’s lab, working on zebrafish. I joined her lab.. A couple of years after I joined in Utah, Tatjana and Alejandro were offered a position in Kansas City, at the Stowers Institute. So I did 2 years in Utah, and 4 years more in Kansas. Still, I graduated in 2015 from the University of Utah. Around this time, Dr. del Pino retired, and there was no one to take over her lab. At that time, as I was finishing my PhD, I was offered the chance to come back to Ecuador and lead the lab. From what I understood, if I wouldn’t take this chance, they would have closed the lab. So I came back! It was a difficult moment because at the time my wife was just starting her PhD. Still, we always wanted to come back to Ecuador. We have always wanted to contribute to the improvement of science in our country. Also, we knew, with my wife, that we wanted to come back to Ecuador, for both, personal and professional reasons. I’ve been leading the lab since 2015. It’s now 8 years, but it feels like the COVID-19 pandemic pushed us back to the beginning. I think I am where I am meant to be though. I can’t complain.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Ecuador, from your education years?

I did my secondary school in a private school – it wasn’t expensive and the teachers were truly excellent. I always had great science teachers, and this definitely influenced my decision, too. They encouraged my curiosity, and pushed me to learn more. In University, I am very grateful to having been immersed in Developmental and Cell Biology since early on. Dr. Eugenia del Pino’s research line was interesting and complex, and she had an incredible network of colleagues around the world with whom she discussed science passionately, and this was intellectually stimulating. I think this was important in my career. Moreover, she had awesome microscopes, and because of the access I had to the microscopes, I learned a lot. She wasn’t always happy about students touching the microscopes, but I used to sneak in and practice nonetheless. This was extremely useful and fascinating for me.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a group leader at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador?

Doing science in Ecuador is very complex. Funding for science is scarce and there are no Ph.D. programs. We as researchers, depend on contracts focused on teaching posts. All Universities focus on undergraduate teaching and there are very few postgraduate programs in research. The COVID-19 pandemic together with political instability has diminished most research funds in Ecuador. We don’t have funding to have vanguard equipment, nor to pay researchers a fair salary. We depend on the research done by undergraduate students. In addition, we have huge teaching commitments – sometimes it’s overwhelming. So my day-to-day involves balancing all this I have supervisory duties, teaching commitments, and I do research. Right now, in the lab, we have 4 research assistants, and 3 undergraduate students doing their undergraduate thesis. I must add that, no matter how hard these appointments are, when you see your undergraduate students graduating, when you see them getting excited by a successful experiment in class or in their research, it is very rewarding. I love to see them advancing in their postgraduate careers.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Ecuador?

I haven’t had many opportunities. I have been trying to start collaborations since I came back from the USA; however, we don’t have funds for travel or host collaborations. I feel that friends and colleagues in Chile, Uruguay, etc. are facing similar limitations. There’s little we can do without resources. Some calls allowing for collaborations are too strict, or open every 3 years. Then there are logistical barriers beyond our control, like bureaucracy, funds access and import restrictions. Still, my mentor Tatjana Piotrowski and dear colleagues including Flavio Zolessi and Andres Kamaid have helped me start our new research project in zebrafish. Although there are scarce funds for research, funds for training are a bit more available, and I’ve been privileged and lucky to receive this type of support to do courses in Chile with Miguel Concha and his research group, or in Uruguay with Leonel Malacrida. When I was an undergraduate student, right before starting my PhD, the American Society of Developmental Biology gave me an award to spend 10 days in Argentina at a workshop, with great scientists in the field from Argentina and abroad. This was life changing because I had the chance to network with them, and learn more about the field, which eventually took me to what would become my PhD lab. Funds for training abroad were vital for my career, and they are vital now for my research, to keep me up to date and to collaborate abroad. I also feel that we lack connection within Latin America – starting from the fact that we don’t always know about all the work being done in the region. I think for this reason, your current work is very valuable to our community – I’m very grateful you’re doing this. Since I came back to Ecuador, I’ve been lucky to attend congresses and conferences of the Latin American Society of Developmental Biology (LASDB), and there is always big excitement to see my colleagues and learn about the wonderful work they are doing. We also share the same frustrations: that reagents are not available, that reagents and other material take forever to arrive, and that it’s impossible to be at the level with well-established labs in the Global North. Funds are in the Global North, and while we (in Latin America) may want to interact more with one another and collaborate together, I feel we don’t have the economic strength to be able to do it. Still., I am hopeful that this will change.

Who are your scientific role models (both Ecuadorian and foreign)?

My role model, and the person who has most influenced my career is Dr. Eugenia del Pino. She not only offered me the chance to join her lab, but she also gave me top quality technical and scientific training as a scientist. She created an environment that was hugely intellectually stimulating. While I was in her lab, I was somehow isolated within my own project, but when I went to the course in Argentina, my mind blew! I had no clue about the wonderful things being done around the globe. Everyone I interacted with in Buenos Aires was an inspiration. It solidified my next steps. Alejandro Sanchez was very important because in addition to the fantastic science he does, he always had encouraging words towards me. After that, I learned a lot from all my mentors in Utah, like Gabrielle Kardon, Mike Shapiro and Richard Dorsky. Tatjana Piotrowski is also a very encouraging mentor, and I loved the science she was doing and what I was able to do in her lab. I was able to spend endless hours in our lab’s confocal, and all the things I was able to see were truly a privilege. I wish to give this privilege to my students too. I try to always have microscopy at hand to show them the wonders of living organisms and development. When I see their wonder, I feel I’m doing things right. I also feel that microscopy has played a huge role in my career, and will continue to be so. I had the chance to learn a lot from expert microscopists and research analysts like Sean McKinney, Richard Alexander and Hua Li at the Stowers Institute – There are many other people to whom I am grateful for their time invested in my training.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Ecuador, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I think there’s a complete dis-balance! I try to keep this in mind. All my mentorship experiences have been under the supervision of important and exceptional women. Nonetheless, I don’t think it was easy for them. Like in many other countries, in Ecuador the amount of women in undergraduate degrees is higher, but the pipeline becomes leaky as we advance through the career. I must say that in terms of professors, the University where I currently am does have a balance, and with female researchers in important decision-making positions. I must also recognize that I’m not the best person to discuss about salary gaps. At a country level there is a huge salary gap – I think it is the same for scientists, but I am not sure about the numbers. There are many disadvantages to being a woman scientist in the country. Any call for positions or funding often privileges those who have more time availability, so being a mother or caretaker is a “disadvantage” in this context. Competition becomes unfair between genders because of this. Also, Ecuador is still very patriarchal, where care-taking duties are still expected to be fulfilled mostly by women. So, women with promising careers tend to not take opportunities that later become a professional advantage -such as studying abroad. I have had the luck to mentor several students, female and male, that right now are starting or advancing in their graduate studies abroad, and I have done my best to support them monetarily while they worked in my lab, but this may not be the rule in the country. Also, I feel that the pressure imposed by such a demanding job as professors, together with the salaries, and lack of job stability, really affects many people, but women in particular. I think the dialogue about gender disparity, and the initiatives to address gender balance and women access to STEM careers in a truly proactive way are relatively recent in Ecuador. We are lagging behind compared to many other countries. At the level of government policies, I think that in Ecuador there’s not enough being done. Still, there are groups of scientists pushing for changes and equity like the Ecuadorian group REMCI (Red Ecuatoriana de Mujeres Científicas). I hope the response from the government to these important efforts is reciprocal.

Are there any historical events in Ecuador that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

Although the Ecuadorian Independence was achieved in 1822, the country never reached a true stability in terms of the economy or politics even. Our history influences our way of thinking and acting, which, for a long time isolated ourselves from the rest of the world. I think this has influenced our scientific history too. Although we have very old Universities, scientific progress occurring in other parts of the world, barely reached Ecuador. I do believe that the number of presidents who have encouraged scientific progress is minimum. Historically, science in the country is seen as something that should have immediate results for pressing economic issues, for example science for mining, petroleum, large-scale agriculture, aquaculture (since we are main exporters of shrimps). So science is only developed if there is economic pressure, but basic science has been barely developed. Important advances in research on Biological Sciences done by Ecuadorian researchers only occurred in the late 1960s with the advent of foreign funding and foreign experts. My mentor and our University were beneficiary of this support. I am proud that many research lines in Biology, now distributed throughout the country, originated in our University. The various political shifts and instabilities of our history, however, have acted as an anchor that has led to our stagnation in terms of research.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Ecuador?

It’s difficult to live in a country that is not your own. Challenges are different for each person. In my case, I feel before living abroad, I was in a bubble of having been trained in what I thought was a resource-rich lab in Ecuador. But even so, access to resources, including papers, were very restricted. So I thought I had state-of-the-art knowledge, until I arrived in the US, where they had access to publications, and saw much younger students with vast research experience and access to literature – more than what I had ever had access to in my career. It was a challenge for me to reach the same level, even to be able to pass the subjects of the first years of the PhD, and then discuss science at the same level. Another challenge was to survive in the USA! The cost of life and the relocation was very expensive. Sometimes people don’t understand that a relocation is super expensive, and having to wait a month for the first salary to be paid seemed like an eternity to me. I was lucky not to have suffered discrimination, or at least not as bad as acquaintances and friends did. The language was also difficult. –Having to join a class of 60 students in a completely different language is not easy. These challenges are often underestimated and I feel Universities and employers should consider this. Finally, a huge disadvantage between native and foreigners in the USA is the abusive taxation that foreigners have to pay. You even have to pay someone to help you file your taxes because it’s so complicated – so all these financial challenges are a true burden.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

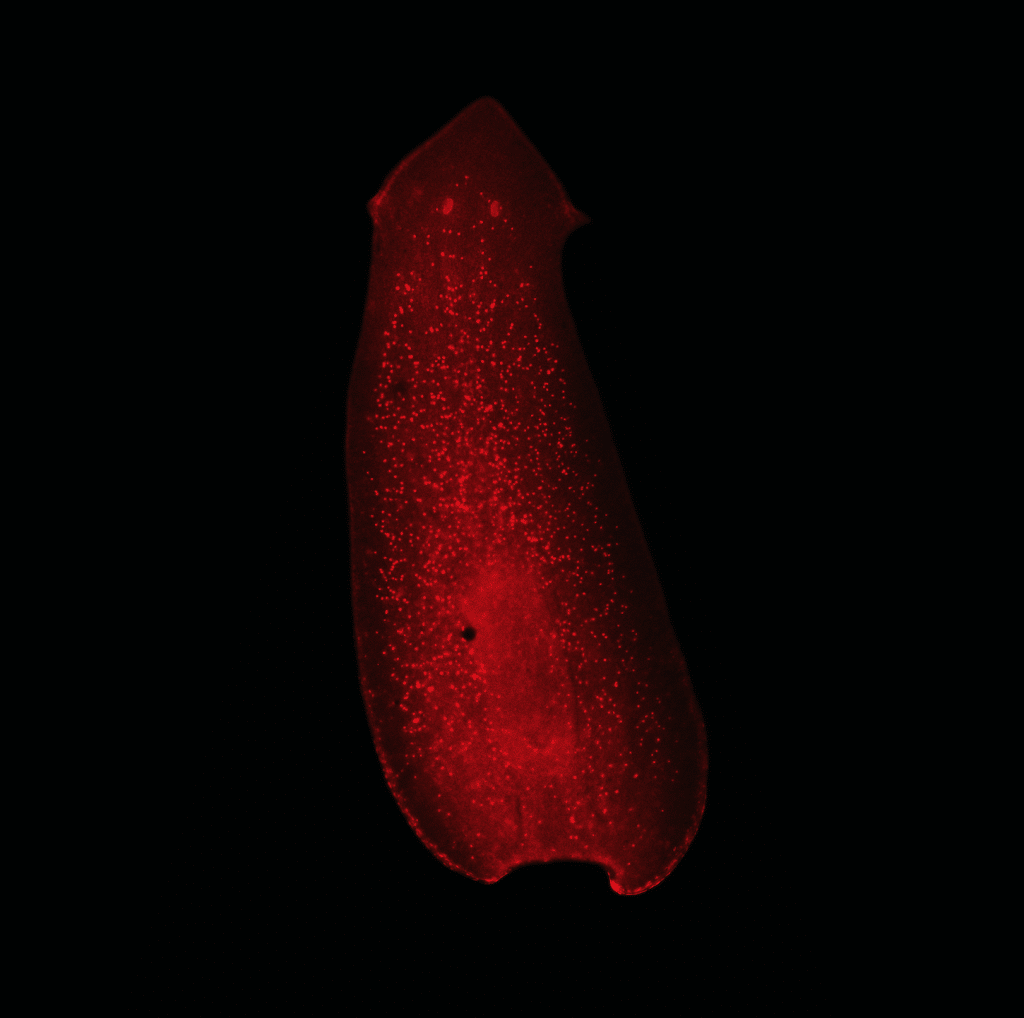

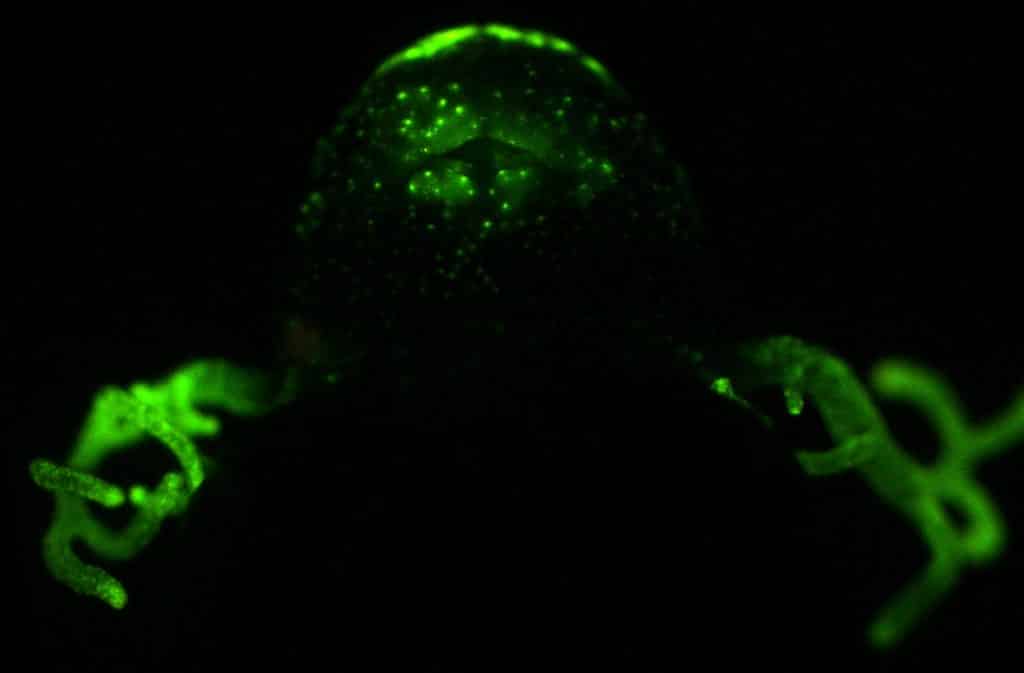

I don’t think I have a favourite type. I feel that I enjoy all of them equally. I love using fluorescence and love the challenge of achieving good images like this. I loved working with zebrafish because of the things you can see. Having a tagged sample with which you can obtain a visually beautiful image and a convincing result, is something extraordinary. I loved the challenge too. For my Ph.D project I had to to follow the lineage of a single cell dividing throughout multiple days – this was slightly frustrating sometimes, because many of my fish would die. Despite loving confocal microscopy, I think microscopy is not static – every year there is a new technique or a new important development. When I came back to Ecuador, I unfortunately had more limited access to microscopes. However, I recently started to become familiar with electron microscopy techniques thanks to a collaborator, and I have found it fascinating too, both SEM and TEM, which is something I didn’t learn as a young researcher, but I’m lucky to be able to do it now. I think what I enjoy most is being able to answer my research questions, and use the most relevant technology to do so.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

There are several extraordinary things. One of my side projects in the lab was working with a zebrafish line called zebrabow – it’s one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen. We were able to find some strange cells from a new lineage – they were mostly in the skin – that moved from the skin to the sensory organs of the lateral line, and would interact there. Some would stay there and some would migrate. This result caused a lot of curiosity in the lab meetings. I devoted a lot of effort to this project during my PhD, however, it didn’t yield any results. Sometime after I graduated, Julia Peloggia, Daniela Münch and Paloma Meneses, all of them new students at Tatjiana Piotrowski’s lab, took over this project and were able to show that these cells were ionophores capable of removing and controlling ions from the extracellular environment, something important for sensory organ function. We published this paper in 2021, and the beautiful pictures I took when I was a student at Tatjana’s lab were included.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Ecuadorian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Experience what it is to do science – apply to internships and other positions that allow you to get lab experience. I always have open doors for interested students for example I try to have them participate in experiments, I encourage them to write abstracts for conferences and that they attend to see the scientific world. I also emphasize that science is difficult – this is not to discourage prospective scientists but to let them know the reality. Science is not the fun bits that appear on Facebook or Twitter, so I try to show them the complexity of science and its pitfalls, so they have a realistic view of the field they are interested in. When they ask me about going abroad to do science, I remind them that it’s the same here and everywhere: the scientific means 10% success and 90% failure. Unfortunately, failure is often not on you. It often depend on being well connected, having adequate funding, and many other variables beyond your bright ideas.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Ecuador, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I try not to be pessimistic, but I don’t see in the near future prospects for microscopy to advance. For example, the country only has 3 confocal microscopes that are not accessible to everyone The part that makes me hopeful is that many researchers who were able to study abroad are now starting to return to the country. And I see great potential in joining forces and coming together to get external funding –I hope I can do my best to acquire those funds, and continue to contribute to the scientific development of the country, together with many colleagues who are aiming to do the same.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Ecuador a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

The country is mega-diverse with climates and micro-habitats that are extremely complex. This diversity has not been fully studied, and is a gold mine for us as scientists! One could fall in love with this wealth and beauty. The visible beauty from our country is the result of complex biological processes that are not fully understood. These processes may allow us to understand ourselves as people and understand our country. There’s been a historical constant of exploiting the natural resources that the country offers, but perhaps a better approach would be to find a way to live together with this diversity, and understand it and protect it better. I think Ecuador is very special, and it’s one of the reasons why I wanted to come back.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)