Enhancing Global Access: interview with CZI grantee Michael Weber

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 24 January 2024

UNLOCKING NEW BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH WITH MODULAR AND SHAREABLE ‘FLAMINGO’ LIGHT SHEET MICROSCOPES

Michael Weber has focused a lot of his career in microscopy development. He is a grantee of the CZI cycle 1 grants to imaging scientists. As part of his project, he helps developing light sheet microscopes called ‘Flamingos’ that can travel between research labs in different locations across the world. His hope is to share microscopy technology in a way that improves collaboration and communication between scientists and developers.

What was the inspiration for your project? How did your idea for the CZI project arise?

The project was in the making before the CZI call, even before I joined Jan Huisken’s lab. I did my PhD in Jan’s lab and my postdoc in Jennifer Waters’ microscopy core to broaden my horizons. I was thinking about the next step in my career and Jan contacted me and we discussed the idea about a new concept of a microscope and even a new concept of a facility. I’m always intrigued by interesting ideas and approaches, so I re-joined Jan’s lab. He and his team had designed a prototype microscope, less streamlined than the flamingo now. There were two key aspects to the project: to make internal development of our own microscope easier – to streamline the process and make it less susceptible to stagnation when there is turnover of personnel. In microscopy development labs you often build each system from scratch with the aim of publishing it, and then the next person would do the same. But from a practial point of view we should not only develop and build new things all the time, but also make sure that some projects have a smooth continuation and are made available to the broader community. The other aspect, more specific to light sheet, is that we really see a lot of potenial in imaging larger, multi-cellular samples, but these tend to be more complex than just cell culture. It is also associated with complications in transporting samples such as embryos or even zebrafish. It’s complicated, and at some point it’s easier to bring the microscope to where the samples are instead. We wanted to be able to quickly lift the optics lab and at least for initial testing, quickly provide a microscope that works and can be modified on site. We can even take the microscope back after this initial testing, and modify it to suit the research question. Collaborators anywhere in the world tell us what they need in terms of technology, we find a good match and provide the setup for a few weeks or months, and then datasets are acquired that can be analysed. In the meantime we can retrieve the microscope and deploy it somewhere else. We can update it with new stage designs, new chambers, or whatever else that needs to be implemented every time the system returns. Of course, there are a couple of hurdles to consider: how to pay for the microscope components and our efforts, and how many microscopes can be in this loop at any given time.

At what point in this process did you first hear about CZI and how did you decide to apply for this call?

It was a great coincidence. The call came out around the time Jan and I spoke about me re-joining his lab. We decided to combine these ideas and use the existing pitch for the flamingo idea. It worked and I started in the lab together with the CZI funding. About how I first heard about it, it might have been in some newsletter or some general form of communication, because the first call made big waves. That’s one of the main aspects of the CZI call, that it was really unique, and it was so welcome in the community. It was just so different, and we knew we had to apply.

How instrumental was the CZI grant in you accomplishing what you wanted to do?

The idea for our project was already there, and the idea of hiring a new person for this project (me) to be the application specialist was already established. What the CZI grant meant is that finance-wise it gave us a lot more freedom. This allowed us to be more flexible with the project and what we needed to get it up and running. Also, because CZI is so open as to how you use the grant money, it means we could explore a lot of extra ideas we had. We explored a smaller laser and realized it was a great addition, smaller cameras, different materials, etc. So CZI allowed us to try some of the most creative and fancy ideas.

You said that this project changed your idea of a facility. How did it do that?

I spent several years of my career in microscopy core facilities and it makes sense for expensive systems to be centrally managed and used, plus it’s incredibly valuable to have microscopy experts on site. This value used to be overlooked. You need well trained people who can train other people. But your typical core facility is always in a certain location and everyone needs to go there, which is fine for many things, but not suitable for everything or everyone. I like the idea that you can turn this around and make the facility move around instead of having people and samples move around. Of course this poses other challenges – managing and scaling up is easier in a stationary facility, but I was eager to give it a try and see what we can learn for future projects.

Some countries have difficulties bringing instruments from abroad, due to associated costs and import taxes, even for demo sessions. How would a mobile facility overcome this barrier?

One way we have been tackling this is in courses. If there is an interesting course, we bring the system there. There is an upcoming course in France, we also brought it to Woods Hole. There are still some hurdles. Sometimes even funding makes it difficult because for some funding, any product of the research is not supposed to leave the lab – maybe it’s a condition to avoid re-shuffling of instruments and material afterwards. The idea of mobile equipment was a strange concept for our university too because most pieces of equipment here have a sticker or barcode identifying each piece, and this allows tracking of the various instruments. It was strange for the administrators to know that some equipment might be here today, but not tomorrow. Another issue is the need to buy parts – this is a smaller issue in the bigger picture. Some are not too expensive. However, you also need people who can build and support an application, which is more tricky. If you start to spread over a large distance, and target labs that have never used a particular technology, this means you have to provide training. In our current model, at each location where the microscope is, it’s used for a different project, which ideally culminates in a great publication later on. The collaboration enables us to provide the microscope, knowledge and time. Right now it’s very easy and accessible to keep it at this level. CZI helped because it allowed us some flexibility, for instance, if a lab doesn’t have enough people or money to pay for the shipping, we cover this. This allows high end experiments even in the early years of a new research lab, which can be very helpful for grant applications. We can help researchers identify if light sheet microscopy is the right imaging technique for their ideas, and they can then decide whether they want to invest in a commercial setup, for example.

In the context of democratizing microscopy, how do you think your project has facilitated that, and what is the future direction of your project, for instance 10 years down the road?

I would hope that at least we can demonstrate that different approaches are possible and that researchers can benefit from this approach. One limitation is the fact that we alone can’t scale Flamingo up to a level that it is an alternative to a commercial setup. Our dream is that other developers feel inspired to join forces in projects like this. This hasn’t really happened, but it’s a big commitment, so I understand if not everyone is joining. But this restricts access to some extent: only a small number of researchers currently have access to a Flamingo – fewer people than want access. But so far, for several scientists, it changed the way they work with their samples and the type of research they do. Many of them didn’t have good access to light sheet microscopes before. In this case, lack of access slowed them down, so having access was a big step forward. It allowed them to apply to new grants for instance, or opened entirely new research avenues. Regarding the future, there are several paths: we could turn the project into a company, but this would change the trajectory of what it currently is, because as a company it can’t be zero in terms of cost. Like cores, we would need to caculate and return the cost. This would be a killer for a lot of projects. Also, we would be competing with other companies who also sell light sheets, so it would need to be a different level operation. Another approach that is much more in line with the original idea behind Flamingo is to convince funding agencies that it is a good idea to ensure continuous support of this and similar projects in the future. But this is difficult – it’s not a traditional scientific project, so it will take some convincing. There are lots of hurdles, but that’s the vision for the next 5-10 years. I think it would be great to have general financial support for the Flamingo for a few systems per year plus one or more experts to take care of them.

The Flamingo project is currently also being established in Latin America. Are there other regions where it has been deployed to the same extent? In Latin America we are talking about 3 setups we will build in the framework of the CZI grant, and that’s certainly the largest individual project of that kind. We have started our work on the project in the US, and now we are transitioning to Germany and aim to cover some parts of Europe as well. Beyond that, we have some ideas with the UK, but of course that’s too far away for us to provide support in person. One idea is to have partner labs that agree with the idea of Flamingo and have someone on site from that institution taking care of the systems and making sure they will be moved around and made accessible. The goal is not to have as many systems in the world as possible, but rather to support specific key projects and then grow the project from there. If it is growing, ideally new people would join, develop something similar or help develop something together. I hope this stays alive beyond our own lab. Internally, we all use these setups for biology projects or optical development projects, so it’s been a success internally. Some things are difficult to plan, though: there are Flamingo microscopes that we planned to provide for three months, and now they have been in the same lab for two years because challenges arise from the biology side – probably something we should always be prepared for in live cell imaging. But the biology is interesting so we want to keep the microscope in the lab, but then we start running out of systems. These are things we need to consider as the project grows. The more it gains interest and usage, the more we can cover special interests.

What have been the greatest successes and the greatest obstacles of your project?

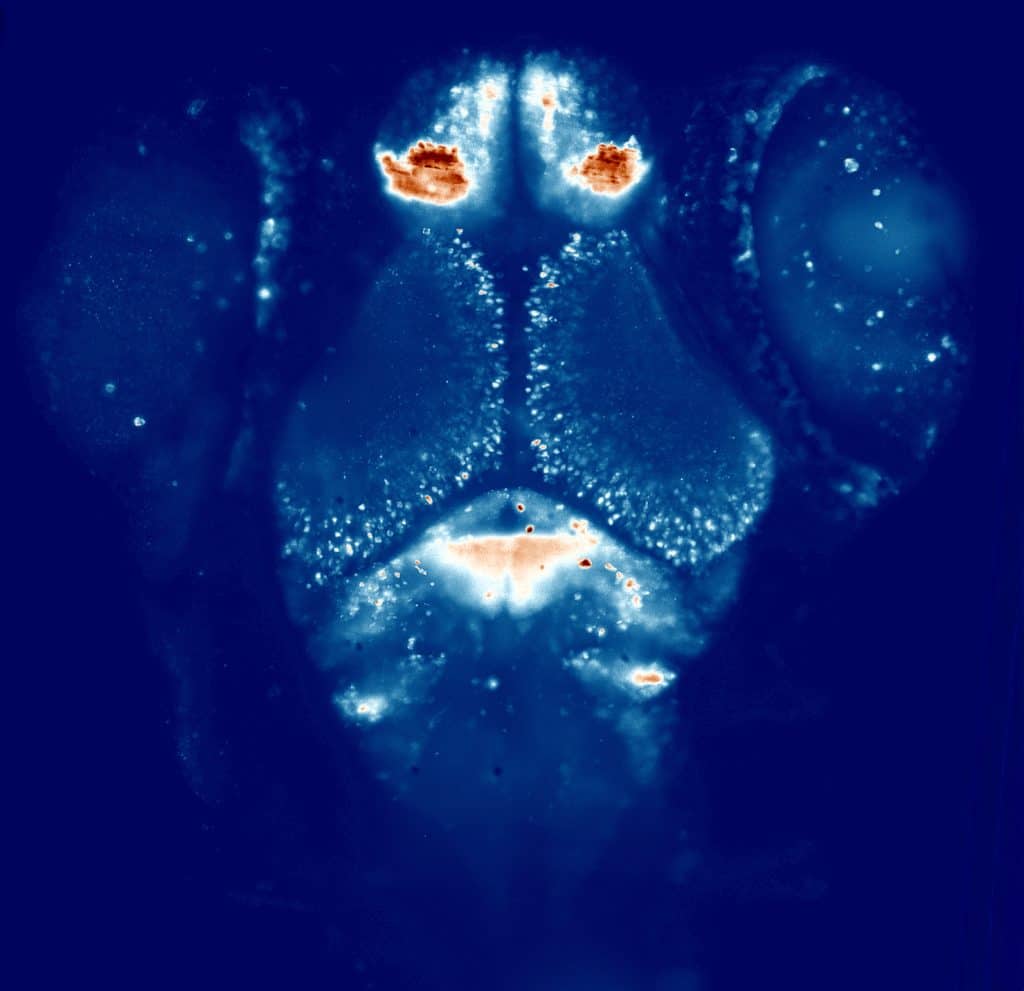

I would say the biggest success is that we made it work in the first place. There were lots of open questions, and I’m amazed at how well things worked and are working. On the technology side, the microscopes are stable and it works for a large variety of samples. We have imaged so many different things and we managed to improve our technology: zebrafish are so stable and so forgiving imaging-wise. Conversely, for example, there are animals that are very sensitive to the material that we use for the sample chamber – so we now adapted to this and learned a lot in the process. The biggest hurdle is how many projects we can support per year with these setups. We were perhaps a bit naïve in our initial calculations. Things always take longer, and it’s not just one experiment: you need to repeat things. So we thought that by the end of the CZI project we would have supported 50-60 labs, and this is not the case. Then of course there were hurdles associated with COVID. In the initial years in the US I used to be a guest scientist in the collaborating labs, and this became impossible during the COVID years. We had to deal with delays like parts not being available for a long time – lasers and motors suddenly took more than a year to be delivered. Unfortunately, the pandemic happened too early in the project so we didn’t have a huge set of data we could suddenly process in our home offices. Nobody expected it to take so long, so we were planning for experiments that we kept postponing and sometimes had to cancel.

Your project addresses several needs including expanding global access, bridging disciplines, and facilitating access in general. What do you think is necessary to facilitate communication between different areas of experise, especially in a project like this? This was always Jan’s approach to science, to try and bring together people from different backgrounds: biologists, physicists, computer scientists, engineers. I came from the perspective of the facility staff, which is similar. You have expensive setups that researchers can book and use. You have to communicate effectively what is important. Communcation is a big part of our lab meetings in general. We have to listen to one another, and put effort into thinking ‘How will I explain this so that everyone understands it?’. I like working in multi-disciplinary environments because it broadens your horizon. I think that’s another value of CZI. Beyond the financial support, it was extremely valuable that they bring together different communities from different disciplines. In the first cycle people were mostly from imaging core facilities, but since then things started to diversify and grow. Now we have people from all fields and regions of the world – just bringing them together has fostered great collaborations.

How does the CZI network help you reach other people whom maybe through other networks you were not able to reach before?

CZI is doing a great job – that’s how I met Alenka Lovy and other collaboratoes from many places in the world. I think it’s a great achievement, and I hope other funding agencies see what’s going on and adjust, and give the option to have similar financial support. CZI strengthens the microcopy community: you have to support facility staff as well as the experts who develop the tools, the software and the frameworks, and those who manage these aspects. These scientists are all vital and need support as well – it can’t just be an afterthought.

Finally, where did the name Flamingo come from?

The name was chosen before I joined the lab. I was told that there was a big lab meeting where everyone could suggest names. The goal was to not have any kind of abbreviation. It should be a name easy to recognize and find. One potential explanation of why the name ‘Flamingo’ could be that the standard configuration stands on one leg – and it travels around the world! It’s good to have a name that’s easy to remember. And our local mechanical workshop told us we should have some of the custom parts made in pink to match the Flamingo colors!

Check out our introductory post, with links to the other interviews here

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)