Enhancing Global Access: interview with CZI grantee Claire Brown

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 24 January 2024

TRAINING AND MENTORING IMAGING SCIENTISTS AND BUILDING IMAGING COMMUNITIES

Claire Brown leads the Advanced Bioimaging Facility (ABIF) in Canada, and she has helped build research and training networks across Canada (Canada Bioimaging) and North America (BINA). Her project aims to develop technology training courses, train-the-trainer programs to train imaging scientists in a range of skills related to imaging science and continue to build and strengthen bioimaging communities. These programs will be disseminated internationally. In addition to her efforts towards training and education, Claire Brown hopes to offer be a mentor to early career imaging scientists and help them build a peer network.

What was the inspiration for your project? How did your idea for the CZI project arise?

My inspiration came while running the facility. When I started, it was basically a bunch of microscopes all around McGill and in individual labs – there was no facility. As I started to try to talk to the different investigators and convince each of them that it was a good idea for me to take their microscope and take care of it in a central facility, I realized right away that education in terms of centralizing access to instruments and technology training were important and that people needed to know how to use these instruments. It was clear to me from the very beginning that training and education is what needed to be done. Right away, I started developing training programs and courses. Now that I’m further into my career, I see that I would like people to have it easier. I think the way I did it was very hard because there were fewer resources available. I had learned microscopy from the top down. I was doing fluorescence correlation microscopy, and I didn’t know how to do Köhler alignment, so I learned everything in a very patchy way. When I developed my course at McGill, I had to learn everything from scratch, and so I’ve always felt that the work I do is more valuable if other people use it too. I feel the effort I put into it is even more useful if others can use it and build on it. In this way mentoring is something that has also been in my mind – mentoring my own team, and other people in the imaging community. This seemed to fit with training and education as well, to mentor people on how to train others. I’m very excited about the train-the-trainer program!

Can you tell us a bit more about the train-the-trainer program you have developed?

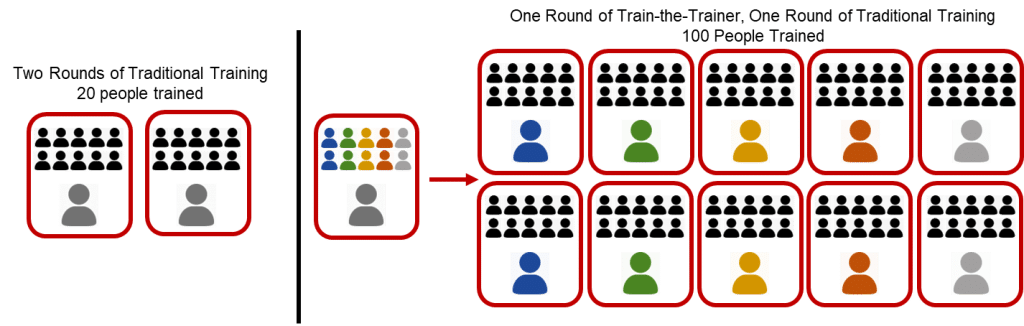

Historically, there were many imaging scientists who took my courses over the years – this is linked to me advertising in my own networks. People would hear about the fundamental and advanced courses we were doing, and half of the participants were imaging scientists from facilities. But they were coming to take the course like everybody else. Eventually, I thought it would be beneficial to train people how to train others – how to run the course, because I can only train 20+ people in any one workshop. Instead, if we train people how to train others, they can take everything back with them and expand this knowledge and access to it. These plans got a bit delayed with the pandemic and everything else. I was talking to Gleb Grebnev from GBI in Mexico last February, and he said there were not a lot of train-the-trainer courses coming up. I thought then, this was the right time to do what I had been planning all this time. The whole concept is to bring people in and show them how we run our course and then give them our material to take back and adapt and use to run their own course. This went really well last July and I feel it has been impactful!

What are the challenges you have faced with this program, especially when you have users with different levels of expertise?

With respect to the different levels, our approach is to treat everyone pretty much the same, to start right at the beginning, but in my experience the difference is just how fast you go through the material. The most challenging users are those who think they already know most things and are not open to learning. It’s difficult because they tend to be disengaged -they are not really listening. When I first started at McGill, we had Zeiss microscopes, but I had used all others – Leica, Olympus, Nikon, but never Zeiss. So I went through the training. I’m the director, but I have never used this model of microscope, or this software, so I try to lead by example. There’s always something to learn, so we made it a policy that everyone gets training.

What do you think is the importance of building imaging communities and citizen science for advancing microscopy and image analysis?

I would say 2 things: one, just the speed at which we can do things. When we built Canada Bioimaging, we basically looked at what GBI was doing and applied it to Canada. When we built BINA, we also looked at GBI and Canada Bioimaging. Alison North had a lot of experience with European groups like Bioimaging UK, so we didn’t have to reinvent the wheel. We saw what was happening around us and tailored it. I think communities accelerate things because you’re not starting from a blank slate. The second thing is that I think by nature we are community creatures. We thrive on relationships. Even if you have a really hard challenge to tackle, and you have someone else who has been through it, even if they haven’t figured it out yet either, it gives reassurance. Especially with my experience throughout my career, I like to talk to people at earlier stages of their careers – and I feel a bit like a cheerleader to motivate them. Especially people who are in a single person core, they are very resilient people to even decide to take that job. So sometimes they need a listening ear, or someone to help motivate them. Personally, I get a lot of satisfaction from that too. If my experience can help others make their life easier, this makes my experience and hard work more worthwhile. You don’t get either of those experiences unless you are in a community with people.

How and when did you choose to apply to the CZI grant?

The first round of imaging scientists grants was only open to US citizens, so once I saw the second call was open to international applicants, I decided to apply. I went to my Dean and made sure that if I applied, they would take the money that they would have otherwise given me for my salary, and invest it in my facility. Luckily I had the support of the university, which is something CZI wanted to see too. I feel they wanted the universities and institutions to understand the value of imaging scientists. I probably heard about the call from Michelle Itano and Caterina Strambio De Castilla, because they were both group leaders for BINA right from the start.

You wrote in your project that you want your expertise and reach to go beyond Canada and even beyond North America. What challenges have you faced with that? And how do you feel the CZI grant has helped you in this endeavour?

When I first reached out to GBI, they didn’t have any contact in Canada. Right away I saw that what they were doing was really interesting, bringing everyone together. When I met Antje Keppler and Federica Paina who at the time was the manager of GBI, we had a Zoom call, and we immediately connected. There are some people whom you immediately can say ‘I want to work with you’, and this is how I felt. We built Canada Bioimaging, and then BINA was formed – they wanted to include Canada so it was a natural fit. BINA is now more established and also helping the Canadian community, so now it’s also easy to reach out and network with other networks in Europe and Latin America and other regions. The approach I’ve taken is that my focus in Canada Bioimaging is on specific technologies- we want to make sure that people who are getting involved, are doing so in a way that it helps their day-to-day activities and research. We started the expansion microscopy group and the lattice lightsheet user groups because these were two things we wanted to do in my facility. I think the traditional way of establishing new methods is not very efficient: you do a literature search on methods, decide what protocol looks most promising, and then try and figure it out with your samples. This is not very efficient, and in addition, the literature doesn’t always tell you all the things in detail, or whether some things are challenging. So right away I thought a way to overcome this and address this better was through user groups. I think the pandemic taught us how quickly we can build a global community through Zoom. I think both, in BINA and Canada Bioimaging, we have to make sure our activities are aligned with the needs of the community. Then people will stay engaged because it’s relevant. I feel that working groups that didn’t succeed came up with a good formula that worked, but then didn’t continuously evaluate ‘is this still relevant?’. I think one has to build this continuously. In general, building a network like BINA is a lot of work, it’s not a one-time effort. BINA is very successful because we have the right people, who are passionate about things, and the community has picked topics relevant to their day-to-day work, and the CZI funding allowed further growth, including hiring two full time people. That’s what really changed things. They can dedicate their time to the network. However, I also felt that my work increased significantly – it created more initiatives, which is great because it’s very stimulating, but you have to find a way to make time to do a lot of things.

What is unique about the CZI grant, compared to other funding bodies? And how do you ensure sustainability of your project?

In Canada there is no funding for this type of work. CZI fills an important gap where there’s otherwise no funding. Regarding sustainability, I was able to convince my dean to give me a research grant from the university for my salary, so I’ve been able to use that to subsidize the salaries of my facility staff. After the CZI funding time, my hope is to have shown the impact that the funding has had, and ensure further support from the institution.

How do you define democratizing microscopy, and what are the long term goals you envisage for your project?

For me, it’s about making the infrastructure and the expertise readily accessible to anyone who needs it. I think this includes flexible fee structures rather than rigid. If a lab is between grants, I think they should be able to use the facility for free to get preliminary data to get other grants. I think right now we have a fair fee structure at McGill. If you’re a McGill user you pay a certain rate, we have a special rate for people who use the facility a lot, and then we have a surplus charge for people from outside the university, but in some ways I don’t think this is fair. I don’t know if you know the little baseball cartoon on equity – I love that cartoon because our culture is so stuck on fair being equal, and equal is not equitable. We are all coming to the table with different challenges and different backgrounds and resources, so I’d like to see more flexibility in how we run facilities. I think a first step is just making them generally open and accessible. In my facility we don’t have any restriction in terms of who can get access, but fees can be restrictive. We have done things like negotiating a project price, or that they come at times when the cost is lower (evening and weekends when the instruments are less busy), but ideally we should have reasonable and accessible fees for everyone. And that’s not how it is right now. In an ideal world, facilities help in several ways, one of them being making expertise available. When the second member of my facility first joined I thought ‘they know a lot about C. elegans and mammalian cells and image analysis’, and all of a sudden we had a whole new range of expertise, in addition to someone else being able to train people in the various instruments. It’s not possible to do everything with one person, so that comes along with centralizing and building things up that way.

What are your long-term expectations with regards to your project?

We got two equipment grants in the last 3 years, we got the Zeiss lattice lightsheet, which is the first two camera model in Canada, and we got the Stellaris 8 which is with FLIM and STED, the first of that generation in Canada. I’ve been 18 years at McGill and I’ve seen million dollar instruments come and go with very little use. And it all comes down to the people: if we don’t have someone on staff who can train people at the level they need, we can end up with a lot of unsuccessful projects. So, for our lightsheet, because we have the CZI funding, I’ve been able to hire a dedicated person for that instrument alone. She’s working 4 days a week on that instrument, and one day a week on general facility work. She’s doing a great job, and is able to really dedicate time with the users in one-on-one assisted acquisition sessions and trainings. Once she’s ready and the instrument is well set, I want to make it a national and international resource. Through BINA, GBI, the mobility funding for train-the-trainer, or the GBI job shadowing programs, she will be able to work with collaborators world-wide. I plan to do the same with the STED and FLIM aspects of the Stellaris, because they are also very unique. With both vendors, we are hoping to further encourage community-building, with corporate field specialists and academics training together and working together.

What is the biggest success story since you started with the project and with CZI?

The most recent that comes to mind is that I came to Mexico last year for the GBI core facility management course, and I networked with many Mexican scientists, who then came to Canada and took my train-the-trainer course in Montreal in July. Then a lot of Canadians from that course are now in the LABIxBINA meeting in Mexico. To me, I just totally see the impact. If it weren’t because of this connection, we probably wouldn’t have met. It’s really satisfying to see the power of connecting people. Another success story in early stages, is with Leonel Malacrida- I met him through CZI. Marcela Diaz, who is the facility manager at the Advanced BioImaging Unit (Unidad de Bioimagenologia Avanzada) in Montevideo, Uruguay came to our train-the-trainer course in July, and now one of Leonel’s students, Maria Jose, is coming to do FLIM on our new microscope in Montreal. I’m going to Uruguay in January for a sabbatical for 6 months to work on running training courses there and on FLIM. On the mentorship side, Leonel was telling me that there are not a lot of female scientists in leadership positions in Uruguay, so I look forward to the chance of meeting young women scientists there. I remember how much I struggled when I started, and how much I would have loved to have a female mentor.

Check out our introductory post, with links to the other interviews here

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)