An interview with Lisandra Vila Ellis

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 23 July 2024

MiniBio: Lisandra Vila-Elis is Assistant Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology at Northwestern University, where she studies the role of a newly discovered endothelial cell population in the lungs, and their relevance to gas diffusion and lung health and disease. Lisandra was born in Cuba, and moved to Ecuador at a young age. She then went to Mexico to study Medicine at Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey (ITESM). During this time, Lisandra had the opportunity to do a research internship that confirmed her fascination for scientific research and opened the door for her to do a postdoctoral project at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, where she specialized in lung vasculature. It was here that Lisandra was first exposed to microscopy. Her work earned her a Pathway to Independence Award from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. At present, Lisandra uses multiple microscopy methods to image the developing lung vasculature. Beyond her scientific research, Lisandra has a strong philosophy about mentorship and is involved in various initiatives at Northwestern University to improve mentoring outcomes. She is also the founder of the podcast series Vascular Crosstalk, where her and her colleagues have spoken to several key researchers in the field of vascular biology, and addressed important topics such as gender equity and careers in science.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I had an unconventional way of getting into science. For the longest time, since I was a child, I knew I wanted to be a medical doctor. I would be out in the street taking the blood pressure of my neighbors at 9 years old. I loved taking care of people, and in addition if they were ill, I was interested in the disease too. So, I went to Medical School. Growing up in Latin America I didn’t know that you could be a scientist for a living – I didn’t know any. In high school I had an amazing Biology teacher- he was an MD- and in one of my first classes we studied Genetics. I fell in love with Punnett squares, and eventually I found out one could genetically engineer mice. I thought “I can become a Genetic Engineer!”. I was fascinated about the possibility of manipulating genes. But I didn’t know any options to do this in Ecuador, where I studied high school. So, I went to Medical School in Mexico, and while I loved my training, I many times got very frustrated because the patients sometimes had diseases that we could not explain. We knew patient associations, but knowledge about the mechanism was very poor. I kept asking my professors “What if we try X or Y approach?”. Eventually, at the end of one of my classes, one of my professors pulled me aside and he asked me “Have you considered doing science? I get the feeling you might actually enjoy that”. So, I started to look for opportunities within my University to get involved, and I found a summer research program. It was here that I met the investigator who became my postdoc PI. That was my first introduction to science! When I finished Medical School in Mexico, I had to do social service. My school had a program with some universities, where you could have a research position. I had a high GPA so I got one of these positions. My social service was as a research medical student at my postdoc PI’s lab. This was in Houston, Texas. Here, I fell in love with science, and became absolutely fascinated about what one can do in science, much more than about what one can do at the bedside.

Was the transition from the medical degree to the scientific and academic line difficult for you?

I just didn’t know anything, truly. My postdoc PI, Dr. Jichao Chen, took a bet on me and I’m forever grateful. He took a bet on me simply from me expressing interest in science, and he taught me how to think about it and how to do it. I think that it’s very helpful at the beginning to do a lot of scientific literature research. It didn’t just help me get immersed in my field, but it also helped me understand the tools that people were using to address key questions. I started developing an understanding of, for example, how you explore a phenotype, or how you delete a gene. It was difficult because I often felt like an outsider: I’m not an MD to the MDs and I’m not a PhD to the PhDs. I had to find my place and I had to learn to think of it as an advantage – it helps me approach research questions in a different way, and it helps me bring a perhaps different perspective to the table. I took my postdoctoral time very seriously to make up for my lack of experience in the scientific field, and I devoted myself to developing the skills that I needed for it, which I knew I didn’t have at the time. I feel overall it worked out well for me. But it was a difficult transition. Moreover, I was doing basic research. It’s not as if I was addressing a translational question with basic research tools. There was no translational aspect in my research. But I loved it! Stars aligned and it was the right combination for me. I found the ‘unpredictability’ of science very exciting and stimulating– with an experiment, even if it doesn’t work, you wonder why. There is never such a thing as a boring experiment! Altogether, my postdoc was 8.5 years long.

You have a career-long involvement in cell biology, vascular biology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

The lung was always my favourite organ, even in Medical School. It might have something to do with my professors. Teachers influence you a lot. I had a fantastic professor for pulmonary physiology, so I already had a great interest in lungs, and when I started my scientific career, it was in a lab specializing on the lungs. It was what I was exposed to, so perhaps it was a bit circumstantial. When I started my first year of research, the lab was focused on lung epithelium, and we had just done a screening using alveolar type 1 cells, which are very thin and large epithelial cells involved in gas diffusion. We showed that these cells produce certain ligands – up to this point no one had discovered that they were capable of regulating anything- but we showed that among the things they were making was Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA). My project became all about understanding why they were making VEGFA, and why the epithelium is talking to the endothelium, and what happens if you start deleting key genes. This is what got me into the vascular field. It is another exciting field, and it has been great for my career. My PI was much more focused on the epithelium, so this project had the potential to give me independence, a way out of the lab, so I could scientifically keep working on what I was working on, without competing with him.

How difficult was it to become a PI, and how is it now? Has it become any easier?

I think that the process is really hard. You have to apply to so many positions, get so many rejections, get ghosted by so many people. Most of the time, you never hear back about a rejection, and you wonder if they are still considering you. It’s an uncertain time. But having good mentors can really help. They ground you when you’re feeling lost. I must say, before I started applying, I did not feel I was prepared to enter the job market. But then when I started writing the documents for submitting my applications, one of these documents is a research statement about what you want your lab to be, and what you are going to study. The day that I wrote that document, I felt so happy!!! It was unbelievable: I could already picture my lab – it’s as if it came to life. This process gave me a sense of confidence I hadn’t had before. Perhaps an unpopular opinion is that I enjoyed the talks I gave during the interviews because I could talk to people about my research and why I thought my research was interesting. I enjoyed telling everyone about what I wanted to do, and how I was going to do it. I really wanted them to ask me any questions they wanted. I was so excited! Overall, it went well, but it was a difficult process. I relied a lot on the network that I had built. I would reach out to them to tell them that I was in the job market, and to ask if they knew about opportunities I could apply to. It’s uncomfortable, but it’s what you have to do.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Cuba, Ecuador and Mexico, from your education years?

I was born in Cuba, and I went to Ecuador when I was 11, and then I moved to Mexico at 18. I always liked school. My elementary school teacher in Cuba was extraordinary. I have always appreciated teachers who try to teach and reach each student in unique ways, rather than one size fits all approaches. I know it can be very challenging (having taught now), especially in a public education system where you don’t have enough resources, and where the number of students per teacher is huge. In Ecuador I attended a great school. Moving from Cuba to Ecuador was very difficult! I was very behind, and I was not used to being behind! In Cuba I was top of the class, and suddenly in Ecuador I wasn’t. One of the main challenges was that I didn’t speak English. My school in Ecuador taught half of the classes in English, and at the time I didn’t speak a word of English. To give you an idea, when I had the first test, I filled in my name, and I didn’t know what ‘date’ meant, so I didn’t fill that (or anything else). That’s how big the gap was. It was a huge blow to my 11-year-old ego! I stayed after school, studying English using the preschooler’s books, where they had me coloring and cutting and pasting, but I was 11. It was brutal. But I was not just behind in English, I was behind in many things – Math for instance. In addition, I was trying to assimilate culturally. Altogether, this is all very tough. But again, I had a fantastic science teacher. I remember the first time we dissected a frog – I fell in love with the lung! The frog was anaesthetized, so I could see it breathing. But frogs, unlike rodents, humans, etc. don’t have multiple lobes. It’s just one sac, which looks like bubble gum. I still remember that frog and its lung, which was fascinating. But my science class was in English, so I had sort of a love-hate relationship. It took me a year to become proficient enough in English. But all my teachers knew my background, and they were all so helpful. I would go home, with all my coursework, and I would sit with a dictionary, translating everything in order to understand it. By the time I went to middle school, I was already very proficient in English. My parents never tried to make things easier for me, and they always encouraged me to take on challenges. During this time, I had another fantastic teacher. He taught English, and we are friends to this day, to the point where he came to my wedding and translated my dad’s speech for our guests. Overall, I think elementary and high school teachers are super important – they are such great influence. I think often of the impact of the teachers I had – it’s so clear to me that I am who I am now, because of their contributions. I now want to play a similar role myself: I didn’t know that one could become a scientist – I would love to give kids the opportunity to see a lab, and see what this career involves.

What do you do on a day-to-day basis as a group leader?

My day-to-day is unpredictable. I have a schedule that varies a lot during the day. I spend a lot of time with the people in my lab, and it’s something I really enjoy. I, sadly, spend very little time at the bench. That said, I try to stay at the bench as much as possible. It makes me incredibly happy. That’s mostly where my time goes. It’s difficult as a starting PI because you’re still getting the hang of it, and you’re being pulled in different ways. Lots of collaborations, lots of meetings, lots of writing, lots of reading to do. But when you’re starting you spend a lot of time developing onboarding documents, development plans for your people, hiring takes a long time because you have to screen a lot of people. Thinking of projects and generating handouts for the students to better understand the project also takes time. So, my day-to-day varies hugely. I don’t have a stable schedule yet, but I’m actually not sure I ever will. It will evolve, but it’s a tug-of-war. Sometimes you must focus on one thing, and sometimes on others, with shifting priorities. That said, I do spend a lot of time at the microscope.

You place high value in mentorship. What is your philosophy on mentorship and why is it important for you?

That is a great question. I think it all depends on the type of mentor my people want me to be and need me to be. I think mentorship should be very individualized because people respond to different things. Part of my philosophy of mentorship is understanding what my trainees need from me and trying to align work and expectations to that. I will give people more freedom or more micromanagement depending on what they need, and these needs tend to evolve over time. But I generally try to give them ownership of the project. I encourage that. I am also a very open person in terms of communication- I have an open-door policy, and I try to foster a safe environment where people can ask questions, even if it is a very simple question. When there are issues, I try to be very open and upfront about this, because I think this is a better way to solve things – to reach a better solution without affecting morale. A good mentor can go a very long way. I feel there is a lot of power in mentorship – it’s a huge responsibility.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of the countries where you have lived? And do you have lots of opportunities now?

I love meeting Latin Americans and connecting. I have tried to do this through the AAMC – the American Association for Medical Colleges. Through this organization I met the only other Cuban scholar I have met in my 10 years here in the US. We happen to share the same name. I think we could increase opportunities recruiting high school students and summer students from various Latin American countries. I think we should really make this effort because representation is super important. It’s important to see people like oneself in positions of leadership: it suddenly makes it possible for everyone.

Who are your scientific role models (Cuban, Ecuadorian and Mexican and foreign)?

There’s a lot of people that I admire scientifically. My postdoc PI, Jichao Chen, had a huge impact in my career, specifically the way he mentored me. I have a lot of gratitude for him. In my current position, my Department Chair, Luisa Arispe is a great mentor. It’s the first time that I have a female mentor – we have a very good relationship and I feel supported in terms of career advice. I know there is someone I can go to, who has shared similar experiences, since she also did her career in Latin America. It’s a great match. I also really admire Anne Eichmann, whom I had conversations with about the 10 years of postdoc that she did. She runs two labs- one here, and one in France. I don’t know how anyone can manage to do that, and in addition, she produces great science. Kristy Red-Horse, who is in Stanford is another fantastic scientist. She does amazing science focusing on Developmental Biology in the heart. I have always looked up to her. She’s also a mom with two kids and successfully runs her lab.

What is your opinion on gender balance in the countries where you have lived, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I grew up in a family where both parents were very empowering to each other. My dad will describe my mom as the most intelligent person he has ever met and they raised two daughters to be challenged, to not take the easy way, and to not depend on anyone. In Medical School I did face gender-related issues, from simple ones such as there being a prejudice that women probably prefer family medicine, and men probably prefer surgery, to more complex ones. For instance, during my Urology rotation, male patients would refuse that I would be the student shadowing the doctor in the room, but it would be ok for my male colleagues to do so. Some patients did not even want to talk about their clinical symptoms if female students were present. As a result, I know very little about urology- I know what the book says, but that’s about it, because male patients would refuse, and the male doctors would accept this. They should have stood up for us – we were paying the same fees for medical education, and we weren’t getting the same opportunities that our male colleagues were. Gynecologists did not have the same issues. Female gynecologists stood up for their students, while being very nice to their patients, explaining why it was important for the students to be present in the room. They always had a female nurse, so even if it was a male doctor with a male student, there was always a female nurse in the room. It’s very worrying actually – many times we had to stay in the waiting room until the physician finished, and then he would debrief everyone about all the cases. But this was unfair and unhelpful. Another thing was that the ORs were very sexist environments, with lots of innuendos. You had to develop a very thick skin to navigate this. There were a couple of scary situations of sexual harassment too, and this of course is more extreme. Later in my career, as a postdoc I was surrounded by male PIs. I experienced and witnessed how women trainees were constantly interrupted, and some wouldn’t let us ask questions. Some would also comment on whether or not a woman can have a career and handle motherhood at the same time. Having to answer these questions is awful. The more senior I became as a trainee, the more male advocates I had. I wish we didn’t need this, but I was happy to have someone in the room who was advocating for me. I slowly became more outspoken about my own science. I think in science it’s been a little better than it was in Medicine. Of course, now with my Chair of Department being a woman, I can ask specific questions and/or seek specific advice when it comes to these issues. We’ve touched on topics like family, or negotiating (eg salary, raises, funding, etc.). She has always encouraged me to stand up for myself. It’s great to have someone I can ask, who sees it from my perspective. I do the same with my own mentees. I don’t think it’s preferential treatment, but we have been exposed to different challenges, and I think it’s important to recognize this, and tailor the advice. It’s important for me to ask them what they need to succeed, and how I can help. It’s important to teach them to advocate for themselves, for instance to ask for raises, to not work for free, to get compensated fairly for their work. But I do this not just for gender, but also background.

Have you faced any challenges as a foreigner if you have worked outside Cuba, Ecuador and Mexico?

Moving as a child to Ecuador was incredibly hard. We didn’t have any family there, so it was my parents, my sister, and me. We had been separated by the government for 5 years before we moved there. It was a difficult experience. The move to Mexico was different because it was a choice I made. I was excited to start Medical School, to join Tec, etc. But it was also very different culturally- I had to adapt again. I learned a lot from my patients though- the way you explain things to patients influences a lot on whether or not they will continue a treatment. I had to be conscious of the terminology they used and understood. I lived in very different areas of Mexico, so the terminology changes too. That said, I enjoy learning about new cultures and integrating into them. It’s challenging but it also has a lot of rewards. Moving to the US was difficult too. I worked for free for a year, because it was part of my social service, so it was a struggle. But I had a job by the end of that year. Immigration was a struggle too, because until I became a citizen here in the USA, my citizenship was Cuban. When I was going to Medical School I almost couldn’t make it. I had obtained a scholarship which only partially covered the tuition, and I could not get a loan: I was neither from Mexico nor from Ecuador. I obviously couldn’t ask for a loan in Cuba. My school had started an MD-PhD program around the time I started, and I was not able to do it because a part of it was paid for by the Mexican government. They couldn’t cover that part for me, and it was unclear if anyone else (myself or my family) could. So it affected me for sure. Here in the US, my experience has always been very welcoming. However, being alone, without a wider network of support, is difficult too. I had a child and I had no one around to help. After having my son during the time I was doing my postdoc, I had to go back to work 3 months after the delivery because I had unpaid leave. My child then entered childcare, which is a breeding ground for every pathogen, and he was getting sick of the time. We had no one to help, and this was very stressful. When you need your family and your community and there is no one around, it’s very hard and one can feel extremely lonely.

Are there any historical events in Cuba, Ecuador or Mexico that you feel have impacted the research landscape of the country to this day?

Maybe I’m not very knowledgeable about all of them. In Cuba, I don’t think we can claim intellectual freedom. There are lots of problems. I’ll give you an example: epidemiological data suffers from a lot of data fabrication – especially when it comes to indexes (index of maternal mortality for example). This has an influence. People who are doing the research have to play by certain rules and expectations of the state, otherwise they won’t be able to do it. There’s an economic impact too- not a lot of people make a lot of money. This has led to a massive exodus out of the country, and this included my family. Ecuador has other issues – there are for example, laws about genetic manipulation, limits a lot the type of research one can or cannot do. It’s in the constitution that you cannot manipulate genetic material, so we can’t even have transgenic mice or anything I use for my research. I would like to see this change- I know that perhaps these laws started with the aim to protect their own biodiversity, but it feels like the people who wrote these laws did not consult any scientist – they didn’t think of the wider implications and impact. Sometimes legislators fiddle with things that they don’t understand and fail to consult with experts prior to approving laws. And they are in the political world making decisions that impact the rest of us. In Mexico, I think the main issue is resources. There is a lot of capacity and potential, but, proportionally, a shortage of resources. It would be very impactful if the government prioritized research.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

Confocal microscopy –one can get stunning images with good resolution. The lung is a beautiful organ to image – it’s full of air with very little tissue but we can get beautiful surface renderings of en-face views of the lung.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

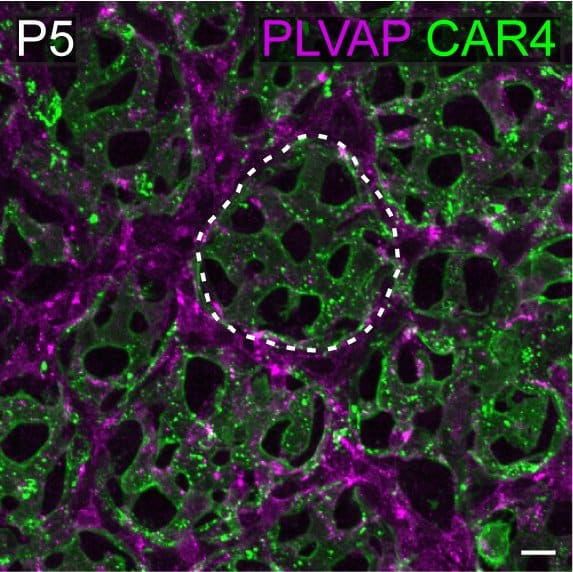

It was on a Sunday when I found my cells! In my postdoc work I found that endothelial cells – the cells that make the vessels – are actually diverse: there’s two distinct populations of capillaries and we were the first ones to describe this. The first time I saw them, it was fascinating. I had tested 25 antibodies, based on bulk sequencing results, to see if any one of them could stain this cell population. One of them worked! I still have the picture from that day, which I took on my phone to send to my PI, to show him that my hypothesis was right. It’s nice when in science things come together, and you gasp and text everyone about a fascinating discovery.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Latin American scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

Believe in yourself. No one can believe in or bet on you more than yourself. Take the time to figure out what you want. This can be a very difficult. Changing directions is not an easy choice, but it’s important to find your path. My other piece of advice would be to network, to trust in your mentors. You should network to increase your number and access to mentors, colleagues, collaborators, peers, etc. You should participate in organizations and associations, volunteer your time and work for your community. You need to invest in your community, so that people know you. And it shouldn’t be just you taking, but giving back. This will be vital. The world is a very small place, and everyone knows someone who knows someone that knows you, or even less degrees of separation. So, work on your network in a very authentic way – don’t use people. And work very hard!

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Latin America, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think a lot of the future lies in machine learning and AI for imaging and image analysis. I think we shouldn’t be scared of this future (with AI) but rather embrace it and help shape it. The other thing is that my ideal world is one where spatial transcriptomics achieves its actual goal. If we could combine fluorescence with this, it would be amazing to get to single cell resolution in combination with transcriptomics.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Cuba, Ecuador and Mexico a special place to visit?

All of them are special. I think Cuba is incredibly special, historically speaking. Being Cuban, for me, is a conflicting feeling because I feel proud and disappointed at the same time. It has produced amazing scientists: Carlos J Finlay (who determined that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquitoes) was my role model when I was in school. There’s a big history of producing science, and culture and music and art, and so in that way I think it’s a special place. Ecuador is one of the most beautiful countries I’ve ever seen – it has 4 different climates and so much biodiversity. It’s amazing, it has incredible food. People are amazing and incredibly welcoming. Altogether, you have so much in one single country. When I say “I’m going home”, I mean Ecuador. That’s where my parents live too, so home is there. Mexico is a blast – it’s so special. I think Mexico has been a great role model for many Latin American countries when it comes to everything. They are role models when it comes to science. Together with Brazil, they are big in Latin America and they represent what the future can look like. I see this for example with the career of Medicine – it’s top of the line. I would go in a heartbeat to Mexico. It’s a historically rich place, with amazing food and culture, and very special for what it means to the rest of Latin America.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)