Damage done, tubules on – Studying membrane damaged-induced lysosomal tubulation

Posted by talcualmal, on 11 December 2025

Author: Luis Bonet-Ponce

Department of Neurology, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, USA.

Department of Biological Chemistry and Pharmacology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

JIP4 and RILPL1 utilize opposing motor force to dynamically regulate lysosomal tubulation

Formally discovered in 1955 by Christian DeDuve 1, lysosomes are rounded organelles that display catabolic activity; degrading extracellular cargo from the endocytic pathway and intracellular material as part of the autophagic pathway. While once perceived as simply “the trash cans of the cell”, our understanding of lysosomes has evolved, recognizing the beautifully dynamic nature of these organelles and their complex cellular functions 2. Indeed, lysosomes play a central role in cellular homeostasis, especially in promoting cell survival and adaptation during stress 3. This is particularly obvious in neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s disease (PD), where lysosomal dysfunction is a disease hallmark 4. A common feature of lysosomal dysfunction is the damage of its limiting membrane, allowing the leakage of hydrolases, ions and other type luminal content, which if left untreated, results in cell death and organ failure 5. To prevent that, the cell triggers different responses to withstand membrane damage 6. Those include lysosomal repair pathways, or termination processes like lysophagy. A few years ago, we described another alternative response to lysosomal membrane damage that relies on tubulation and membrane sorting 7,8. We called this process LYTL for LYsosomal Tubulation/sorting driven by LRRK2 7–12.

How super-resolution microscopy helped us identify LYsosomal Tubulation/ sorting driven by LRRK2 (LYTL)

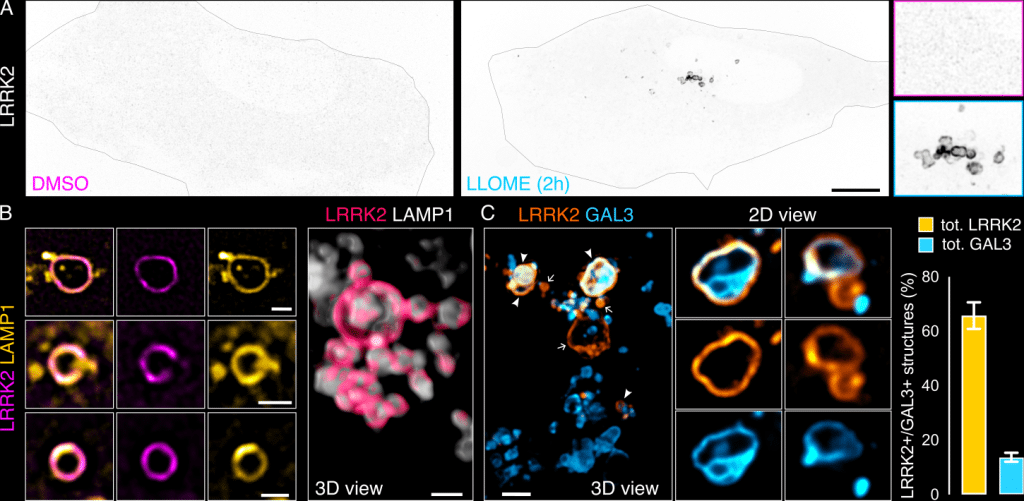

When I joined the Cookson lab for my postdoc, I was intrigued by a large scaffolding kinase named Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 or LRRK2. While known to be associated with familial 13 and sporadic PD 14, its cellular function was unclear. A seminal paper in 2016, showed that LRRK2 can phosphorylate a substrate of RAB GTPases 15, suggesting a membrane trafficking role. This was hardly obvious, considering the diffuse cytosolic distribution of the protein in cells (Fig. 1A). What our lab and others discovered was that upon induction of lysosomal damage, LRRK2 would translocate to the lysosomal membrane (Fig. 1A-B) 7,16,17. We know that LRRK2+ lysosomes are damaged by the fact they are also decorated by Galectin 3 (GAL3) (Fig. 1C); a protein recognizing luminal glycans that are only accessible through membrane holes 18. Our data suggested that lysosomal LRRK2 was not involved in repair nor lysophagy 7,12, so what was LRRK2 doing there? To answer this question, we took a mechanistical approach: through a series of experiments using unbiased proteomics, organelle isolation, proximity biotinylation, pharmacology and biochemistry, we discovered that LRRK2 recruits and phosphorylates at least nine different RABs 7,12. Interestingly, the phosphorylated RAB proteins can bind to two different effector proteins from the same protein family: the RILP-Homlogy Domain (RHD) protein family. The RHD protein family is formed by five members (RILP, RILPL1, RILPL2, JIP3 and JIP4), and their common feature is the presence of two RHDs (RHD1 and RHD2) 19. Our data suggested that RILPL1 and JIP4 were the two RHDs acting as effectors in this context. I was able to identify blurry structures that were positive for both RILPL1 and JIP4, but negative for LRRK2 and typical lysosomal membrane markers (LAMP1/2, LIMP2, TMEM192, LAMTOR4…) 7–9.

Figure 1. LRRK2 recruitment to membrane damaged lysosomes. (A) U2OS cells transfected with HaloTag-LRRK2 were treated with DMSO or LLOME (1 mM, 2h). (B) Live cells treated with LLOME, exogenously expressing HaloTag-LRRK2 and LAMP1-mCherry. (C) Cells transfected with HaloTag-LRRK2 and GFP-GAL3, treated with LLOME for 2 h. Graph shows the % total LRRK2+ lysosomes that colocalize with GAL3 (yellow) and the percentage of total GAL3+ lysosomes that colocalize with LRRK2 (cyan) per cell. Scale bar (A)= 10 mm; (B,C)= 1 mm. Figure from Bonet-Ponce et al. 2025, and made available under a CC-BY 4.0 license

We could not identify the nature of these blurry structures until we observed the cells under a super-resolution microscope. For these experiments, we used a Zeiss Airyscan and a Nikon SoRa (both around 120 nm resolution, after deconvolution). The blurry structures became stunning tubular membranes that emanate from the LRRK2-positive lysosomes (Fig. 2A). We were really confused by the fact that all lysosomal markers, along with LRRK2, were absent from the tubules, suggesting they could be membranes from different compartments (Fig. 2B). However, after using correlative light-electron microscopy (CLEM) focused ion beam- scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM), we confirmed a continuous membrane at the ultrastructural level, from the vesicle part of the lysosome to the tubules (Fig. 2C). These were the first LAMP1-negative lysosomal tubules described at the time, suggesting a different nature and function to the LAMP1-positive Lysosomal Reformation (LR) tubules 20–24. Live-cell imaging experiments, first with Fast Airyscan, then later with SoRa, showed a very dynamic tubular behavior with constant elongation and retraction events. A third and less common group (~20% of the time) would result in membrane fission and vesicle sorting (Fig. 2D) 7,8.

Figure 2. A new process of lysosomal tubulation under stress: Lysosomal Tubulation/sorting driven by LRRK2. (A) Difference between confocal and super-resolution microscopy in observing LYTL tubules stained with JIP4. (B) Live cells treated with LLOME, exogenously expressing HaloTag-LRRK2, mNeonGreen-JIP4 and LAMP1-mCherry. (C) CLEM FIB-SEM of LYTL tubules display a continuous membrane from the lysosome to the tubule. (D) Live cells fissioning tubule into vesicles, stained with mBaoJin-RILPL1. Scale bar= 2 mm. Figure adapted from Bonet-Ponce et al. 2025, and made available under a CC-BY 4.0 license

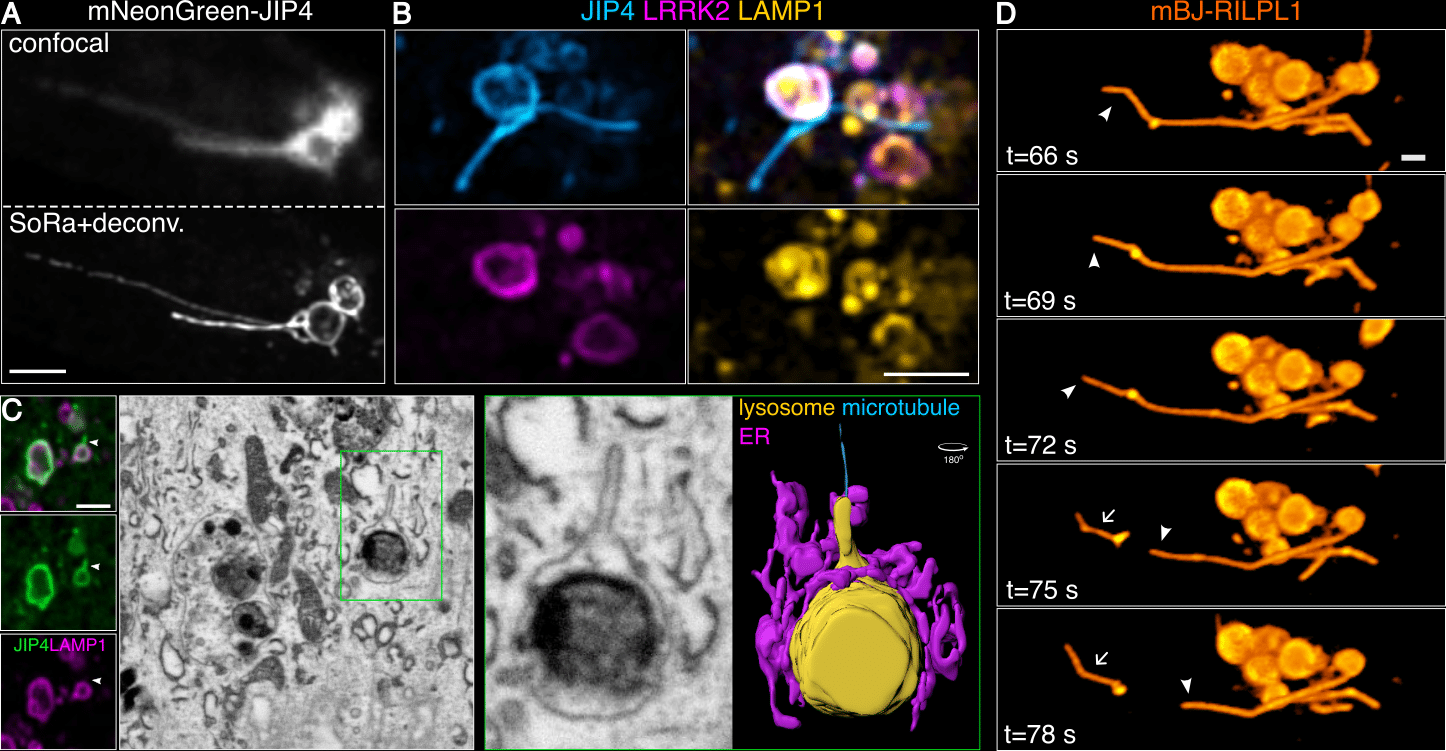

Lysosomal tubule regulation: tyrosinated microtubules

We realized that in trying to understand the role of LRRK2 on lysosomes, we had found a new cellular process. As a cell biologist, my first question was how is this tubulation process regulated? Given that our CLEM data showed contact of our LYTL tubules with microtubules (Fig. 2C), and that nocodazole almost completely blocks tubulation 7, we inferred that LYTL tubules grow on microtubule tracks. We were able to confirm this by live-cell super-resolution microscopy, observing also the movement of the released vesicles through microtubules 12. Given the importance of ɑ-tubulin posttranslational modifications (PTMs) on motor affinity to microtubules 25, we wondered if LYTL tubules have affinity to acetylated microtubules or tyrosinated microtubules; known to exclude each other and mark two distinct microtubule populations 26. Interestingly, we observed a much higher affinity of LYTL tubules towards tyrosinated microtubules than acetylated ones (Fig. 3A). Importantly, Tubulin Tyrosine Ligase (TTL) knockdown (the enzyme that adds the tyrosine residue to the c terminal tail of ɑ-tubulin) heavily reduces tubulation 12, further confirming the role of ɑ-tubulin tyrosination in tubule elongation. Fissioned tubules are also transported via tyrosinated microtubules (Fig. 3B), suggesting a conversed microtubule transport system pre and after membrane fission. When co-stained with the centrosome, we observed that tubules grow in the opposite direction, meaning towards the microtubule plus-end; consistent with a kinesin-dependent elongation and dynein/dynactin-dependent retraction.

Figure 3. LYTL tubules move through tyrosinated microtubules. (A) Cells transfected with 3xflag-LRRK2 and mNeonGreen-JIP4 were treated with LLOME, fixed and stained with anti-acetylated and tyrosinated a-tubulin. The LYTL tubule fraction contacting each a-tubulin PTM was quantified. Unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction was applied. (B) Cells transfected with 3xflag-LRRK2, mNeonGreen-JIP4 and Tag-RFP-A1YaY1 (tyrosinated microtubules) were treated with LLOME for 2 h and analyzed live. Scale bar (A)= 10 mm; (B) = 2 mm. Figure adapted from Bonet-Ponce et al. 2025, and made available under a CC-BY 4.0 license

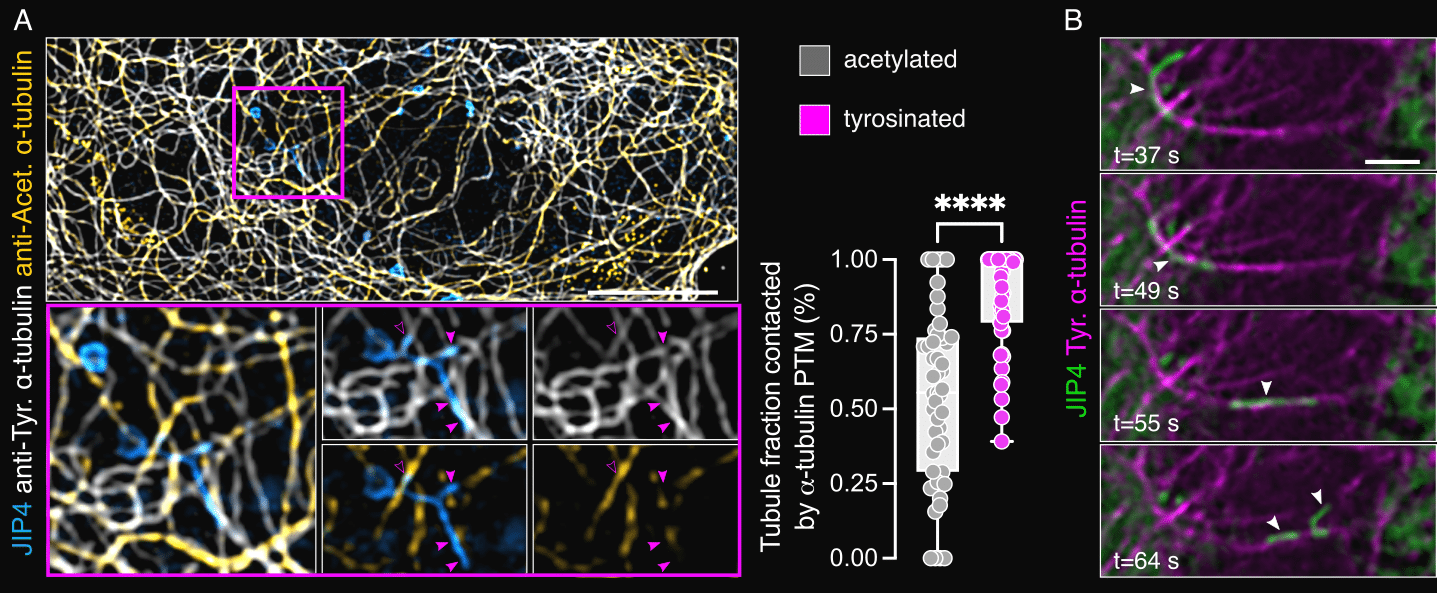

Adaptor proteins promote opposing functions

Previous work had clearly established that most RHD proteins work as motor adaptor proteins 19. RILP is a dynein adaptor that binds to p150Glued of dynactin and the LIC subunit of dynein. RILPL2 works as an actin motor adaptor, binding to MyosinVa. JIP3/4 are large adaptors that can bind to both dynein/dynactin and kinesins. We then asked: could JIP4 and RILPL1 act as motor adaptors for lysosomal tubule elongation or retraction? JIP4 knockdown led to shorter tubules and reduced tubule number, suggesting a role on tubule growth 7,12,19. Conversely, RILPL1 knockdown had the opposite effect: more and longer tubules 12. We later observed that RILPL1 physically binds to p150Glued, but not LIC, suggesting that RILPL1 might act as a dynein adaptor by binding to the shoulder dynactin subunit p150Glued 12. We are currently working towards understanding the biochemical and structural nature of that binding, as well identifying the kinesin that is binding to JIP4. Interestingly, RILPL1 knockdown reduces tubule dynamics and membrane fission, suggesting that LYTL requires a dynamic elongation/ retraction balance for dynamic behavior.

What’s next?

The big unanswered question is: what is the cellular role of LYTL? We’re now tracking the destination of LYTL-associated vesicles and have found that they preferentially interact with healthy lysosomes, although we haven’t yet observed any fusion between the two structures. This finding opens up a series of new questions. Could these vesicles be mediating lipid transfer? Do LYTL vesicles ever fuse with the plasma membrane, potentially releasing lysosomal material into the extracellular space? Are they transporting specific cargo, and what is their proteomic and lipidomic composition? Answering these mechanistical questions will be essential if we want to tackle the most important biological question of all: what role does LYTL play in Parkinson’s disease? I opened my lab about two years ago (Oct 2023), and we currently trying to answer these questions. The Bonet-Ponce lab (https://bonetponcelab.com) studies lysosomal membrane damage, and its link to Parkinson’s disease. We are interested in how the cell responds the lysosomal membrane damage, and how these responses are working in cells that carry lysosomal disease variants.

References

1. de Duve, C., Pressman, B. C., Gianetto, R., Wattiaux, R. & Appelmans, F. Tissue fractionation studies. 6. Intracellular distribution patterns of enzymes in rat-liver tissue. Biochem J 60, 604–617 (1955).

2. Ballabio, A. & Bonifacino, J. S. Lysosomes as dynamic regulators of cell and organismal homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21, 101–118 (2020).

3. Zoncu, R. & Perera, R. M. Built to last: lysosome remodeling and repair in health and disease. Trends Cell Biol 32, 597–610 (2022).

4. Klein, A. D. & Mazzulli, J. R. Is Parkinson’s disease a lysosomal disorder? Brain 141, 2255–2262 (2018).

5. Wang, F., Gómez-Sintes, R. & Boya, P. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cell death. Traffic 19, 918–931 (2018).

6. Radulovic, M., Yang, C. & Stenmark, H. Lysosomal membrane homeostasis and its importance in physiology and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2025) doi:10.1038/s41580-025-00873-w.

7. Bonet-Ponce, L. et al. LRRK2 mediates tubulation and vesicle sorting from lysosomes. Sci Adv 6, (2020).

8. Bonet-Ponce, L. & Cookson, M. R. The endoplasmic reticulum contributes to lysosomal tubulation/sorting driven by LRRK2. Mol Biol Cell 33, ar124 (2022).

9. Kluss, J. H. et al. Lysosomal positioning regulates Rab10 phosphorylation at LRRK2 lysosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119, e2205492119 (2022).

10. Bonet-Ponce, L., Kluss, J. H. & Cookson, M. R. Mechanisms of lysosomal tubulation and sorting driven by LRRK2. Biochem Soc Trans 52, 1909–1919 (2024).

11. Bonet-Ponce, L. & Cookson, M. R. LRRK2 recruitment, activity, and function in organelles. FEBS J 289, 6871–6890 (2022).

12. Bonet-Ponce, L. et al. JIP4 and RILPL1 utilize opposing motor force to dynamically regulate lysosomal tubulation. J Cell Biol 224, (2025).

13. Paisán-Ruíz, C. et al. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 44, 595–600 (2004).

14. Simón-Sánchez, J. et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet 41, 1308–1312 (2009).

15. Steger, M. et al. Phosphoproteomics reveals that Parkinson’s disease kinase LRRK2 regulates a subset of Rab GTPases. Elife 5, (2016).

16. Eguchi, T. et al. LRRK2 and its substrate Rab GTPases are sequentially targeted onto stressed lysosomes and maintain their homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E9115–E9124 (2018).

17. Herbst, S. et al. LRRK2 activation controls the repair of damaged endomembranes in macrophages. EMBO J 39, e104494 (2020).

18. Maejima, I. et al. Autophagy sequesters damaged lysosomes to control lysosomal biogenesis and kidney injury. EMBO J 32, 2336–2347 (2013).

19. Celestino, R. et al. JIP3 interacts with dynein and kinesin-1 to regulate bidirectional organelle transport. J Cell Biol 221, (2022).

20. Yu, L. et al. Termination of autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR. Nature 465, 942–946 (2010).

21. Boutry, M. et al. Arf1-PI4KIIIβ positive vesicles regulate PI(3)P signaling to facilitate lysosomal tubule fission. J Cell Biol 222, (2023).

22. Dai, A., Yu, L. & Wang, H.-W. WHAMM initiates autolysosome tubulation by promoting actin polymerization on autolysosomes. Nat Commun 10, 3699 (2019).

23. Du, W. et al. Kinesin 1 Drives Autolysosome Tubulation. Dev Cell 37, 326–336 (2016).

24. Rong, Y. et al. Clathrin and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate regulate autophagic lysosome reformation. Nat Cell Biol 14, 924–934 (2012).

25. Roll-Mecak, A. The Tubulin Code in Microtubule Dynamics and Information Encoding. Dev Cell 54, 7–20 (2020).

26. Katrukha, E. A., Jurriens, D., Salas Pastene, D. M. & Kapitein, L. C. Quantitative mapping of dense microtubule arrays in mammalian neurons. Elife 10, (2021).

(1 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

(1 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)