An interview with Flavio Zolessi

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 28 June 2022

MiniBio: Dr. Flavio Zolessi is a group leader and head of the Cell Biology Unit at the Faculty of Science at Universidad de la República in Montevideo, Uruguay. He is also an Associate Researcher at Institut Pasteur Montevideo, Researcher Grade 4 of Programa de Desarrollo de las Ciencias Básicas (PEDECIBA) and Reseacrher Level II at the Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (SNI), all in Uruguay. He was previously Head of the Microscopy Unit at Instituto Pasteur Montevideo. His research focuses on understanding cell polarity and neural differentiation using zebrafish as models. Flavio did his undergraduate and graduate degrees in Montevideo under the supervision of Dr. Cristina Arruti, and later went to the UK, to the University of Cambridge to the lab of Dr. Bill Harris to continue his work. He has a long-standing interest and involvement in optical microscopy, and is a member of microscopy and developmental biology networks in Latin America and worldwide.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

It’s difficult for me to point out the actual beginning of my inspiration to be a scientist. Ever since I was a young kid I always loved science. Because of the things I was interested in and passionate about as a kid, I realized this could be the career I wanted to pursue. Even the way of facing life. It all started with my interest regarding animals and nature, and later building and unbuilding machines, and later came my interest for Chemistry. At some point I made a small lab at home where I would carry out small experiments – which would frighten my mother a bit. As a kid I was also lucky that there were very good documentaries at the time. One of those series was Jacques Cousteau and ‘The Undersea World’ – I had all the books too. And the other was ‘Cosmos’ by Carl Sagan. They both covered different aspects of the natural world and this fascinated me. I had no choice but to pursue a scientific career. I considered other options, but only temporarily: Medicine, for instance, due to my inclination towards medical aspects of biology and the fact that my father was a doctor. But soon I realized this was not my ‘calling’. Biology was truly what attracted me (despite my family not understanding what this degree was about).

You have a career-long involvement in cell biology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about this path and what inspired you to choose these paths?

I studied a BSc in Biology – when I started my degree, only in the second year was the degree of Biochemistry opened, in 1990. I tried to switch because I was more interested in the molecular aspects of Biology, but I couldn’t do the switch. We were among the younger students wanting to study Biochemistry, and the ones more senior to us had been working very hard to make this degree happen, so they had priority. We could still study the courses, but not officially Biochemistry as a degree. But still, as a student I was drawn to cell biology, which is the Unit I now direct. My BSc, MSc and PhD was all in Cell Biology. Although in my earlier education years I didn’t have a lot of mobility, I did go abroad for a postdoc to the UK. I went for two years and a half to Cambridge, to the lab of Prof. Bill Harris. And then I came back to Uruguay. I had kept a teaching position here in Uruguay in the department of Cell Biology.

Specifically about why I became inspired to study Cell Biology, it’s an interesting story which I like to share. When I studied high school, we studied this subject, but it was not at all something I liked. I didn’t know why, but when I entered University, I became really interested in it. What had happened probably was that perhaps in high school the subject was not taught in a way it was appealing, or attractive. What I like most about Cell Biology is everything related to cell differentiation, specifically polarity. The cell rearranges structures and functions throughout differentiation. This morphological and functional transformation is something I find fascinating. I arrived to this question particularly in my postdoc, when I worked with neuronal cell differentiation. This is something we kept even now as an independent researcher. This is what I find most exciting now, but of course this can change with time – as scientists we are all the time renewing and evolving ideas.

About microscopy, this came very early on in my life. I was always interested in the microcosmos. I think I can pinpoint some things. I believe for my 12th birthday, my grandfather and father gave me two wonderful gifts. My grandfather gave me a small monocular microscope, and my father gave me a wooden box with histology sections that is very dear to me. My father studied Medicine, and during his studies, the department of Histology used to prepare sections that were sold to medical students so they could study for this subject – they could then have their own wooden box to which they added slides as they progressed in their career. So my father bought slides throughout his career, and he had a beautiful collection with about 80 slides by the end of his degree. And he gave me this. So both gifts together were fantastic and fascinating. Unofficially, I started studying Histology since I was 12 years old 🙂 I was very lucky.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Uruguay, from your education years?

What is unique in Uruguay, which is perhaps rarer in other countries, is that there are teaching positions that can be occupied by students even. The Universidad de la República has 5 categories of teachers, which for all implies that one has to do teaching AND research. The first category (grade 1) is reserved for undergraduate students (and up to 5 years post-graduation) – so really specific to students. Then in grade 2 you can aspire to a full position, which is tenured. It is evaluated every few years, but it is a permanent position. When I left Uruguay to do my postdoc in the UK, I had a grade 2 position. This meant I could go abroad (but not for so long), and then I had a position waiting for me when I came back to Uruguay. Now I have a grade 4 position – and grade 5 position doesn’t exist currently in my department so I currently occupy the highest position.

Working abroad as a postdoc I joined a very big lab with many postdocs from all over the world. I realized that in Uruguay our early careers allow us to study a very broad range of subjects: it’s a more generalist education, while in other places perhaps they specialize very early on. I think this generalist education has the advantage that it allows you to understand a biological question or problem in a more global way, rather than immediately in its more specific or narrow aspects. I think we get a very solid education in this sense. Perhaps a disadvantage is that we are not immediately (right after a BSc degree) ready for lab work – while perhaps in other countries they are. But the knowledge we, in Uruguay, graduate with is very broad and applicable to any scientific question or job one wants to pursue.

That said, the laboratory practicals become progressively complex as we advance in our studies. The limiting factor is that, like other Universities in Latin America, there is no limit to the amount of students that can join a certain degree (eg. Biology), so sometimes the number of students joining in first year, is huge. What often happens though, is that those numbers quickly fall too, simply because many students realize perhaps this degree is not what they expected or wanted. In Uruguay, between the degrees of Biochemistry and Biology, at Universidad de la República we get about 500 students in the first year. So the practicals organized for this number of students have to be less frequent, and simpler, at the beginning. Later, as the students gain more experience and the numbers become more manageable, we can do more complex practicals, and more frequent. For instance, the course of Cell Biology has weekly practicals of 3 hours. Still, around this time, we are talking about 150 students, so it is still a big number. We have another course, on Developmental Biology, which is more of a specialization, whereby the number of students is much lower (10-20). With these students we can do much more complex and versatile practicals, sometimes daily. But as part of the BSc, students have to do a small dissertation which should involve between 6 months and a year of practical work (or any form of research). Here the student already does original research, addressing a specific scientific question while acquiring expertise in several lab tools. But this is still not enough to “form a scientist”: as we know this requires a lot of investment and hours of work until one is a professional scientist.

Can you tell us a bit about your path as a professional microscopist?

When I did my PhD there were no confocal microscopes in Uruguay. We had in the lab widefield and epifluorescence microscopes and this is what I used for my PhD and all my studies. My dream at the time was to be able to lay hands on a confocal microscope one day. This happened when I went to Cambridge – there I was able to do time-lapse imaging on embryos – this was the dream: we were able to label cells in an entire zebrafish embryo, and see the entire process of modifications, differentiation and specification, and generation of the different cell types. I was able to do movies that allowed us to see these processes. I discovered a new world! I think as a cell biologist, microscopy is inevitable. There are other tools but microscopy is central, and I had a natural inclination towards this area.

From left to right: Lucía Veloz, Gonzalo Aparicio, Magela Rodao, Camila Davison, Flavio Zolessi, Lucía Mustto, Santiago Bosch, Santiago Licandro.

Can you tell us a bit about your experience leading a microscopy Unit?

This was a great experience. It was almost a coincidence. A mixed group was formed between the Faculty of Science at Universidad de la Republica and Instituto Pasteur, and me and my students were offered a place for 5 years that this agreement lasted at the time. We had tasks towards both institutions, and due to my expertise in microscopy I became the leader of the Microscopy Unit (now known as the Advanced BioImaging Unit). It was a transition period whereby the BioImaging Unit separated from the Cell Biology Unit, and became responsibility of Dr. Pablo Aguilar. He asked for my collaboration and then we became 3 people (myself, Pablo Aguilar and José Badano) in charge for microscopy. Later Pablo moved to work in Argentina, and I became the head of Unit. This was for a time, until the current director, Dr. Leonel Malacrida, joined in this position. Among my tasks as head of unit I was able to actively participate in the purchase of some confocal microscopes and choose all the configurations and hardware and equipment. It was very educational for me, and an experience in which I learned a lot.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Uruguay?

I have had some chance to collaborate with Latin American scientists, particularly Argentinian, Chilean and Brazilian – and later on Peruvian and Mexican, but more in the area of the work I do on zebrafish – we have the LAZEN (Latin American Zebrafish Network or Red Latinoamericana de Pez Cebra). This is a very strong community built with the aim of facilitating interactions, networking, training, exchanging knowledge and material, etc. This works really well. In terms of microscopy, I believe this is one of the main aims of the current microscopy direction and across Latin America – to make the most out of the Latin American Bioimaging network.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as an Uruguayan researcher, working abroad?

I have only ever worked for a significant amount of time in the UK. Perhaps not a challenge, but more on the funny side- I have been asked whether Uruguay is an African country, or a country of Eastern Europe something of that sort. We are so few Uruguayans in the world that this is almost expected though. I personally don’t think I faced any major challenge. Cambridge is a very cosmopolitan place, and the lab I joined was very welcoming. I was the only Latin American and Spanish speaker even. I already spoke English, but the majority of the lab was not native. So we sometimes spoke English incorrectly, almost to see who could speak it worse. Altogether, I had a lot of independence during my postdoc, so it was a great experience.

Who are your scientific role models (both Uruguayan and foreign)?

For me it was very natural that my mentors were my role models. The people I worked closest with – my PI at the beginning of my career was Dr. Cristina Arruti – she supervised my BSc, MSc and PhD. She taught me a lot – she was super organized! I’ve never been very organized, but I improved thanks to her. And then Dr. Bill Harris, a completely different personality – it was fantastic to do a postdoc with him. He was super open-minded. Before I joined his lab I hadn’t even met him in person – we had exchanged some emails but I met him personally only when I arrived to his lab. We spoke quickly about how the project would work, and then he gave me all the freedom. I began immediately to do experiments in the lab, and he was truly open minded with his whole lab. I have tried to acquire and apply the positive aspects from both of them, to create my own model of mentorship. This is without being like either of them, because at the end of the day, I’m very different to both. I think it’s important to see the best in one’s mentors – sometimes it’s hard because it’s easier to focus on their faults, but no one is perfect. Everyone has something to teach, and being able to extract the best of what someone has to give and make the most of it, and grow, is important. I feel privileged that I had a wonderful relationship with both of them.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Uruguay, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

In Uruguay, as in the rest of the world, there is still an important difference between men and women representation. There are more women in the degree of Biological sciences, and they remain a majority during the BSc, MSc and even PhD, but only very few are in leadership positions. This, even today, remains present in Uruguay. It has improved with the years. In the past the very few women that reached these positions almost necessarily had a strong personality because of how difficult an environment it was for them. For me it was natural to work with Cristina. As a leader now, I feel we have a lot to learn from one another when it comes to genders and leadership. I think with time we will correct the gaps that exist in terms of gender equity. These changes take generations, but I see improvements.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

Optical microscopy in general. From the very first time I used a fluorescence microscope and saw the images, I became fascinated. At present, I love confocal microscopy (and its variations) – but if I had access to other types of microscopy, this might change. I have tried a little bit super resolution, but to me… I just love to see things with my own eyes (rather than something that requires a huge amount of post-image processing). I think other than STED, most super-resolution microscopes require this intense processing so my favourite remains confocal. I think optical microscopy won’t become obsolete any time soon. I’ve always been very visual – I love visual arts and optical microscopy is very visual. Moreover, doing live imaging is the dream of any cell biologist!

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

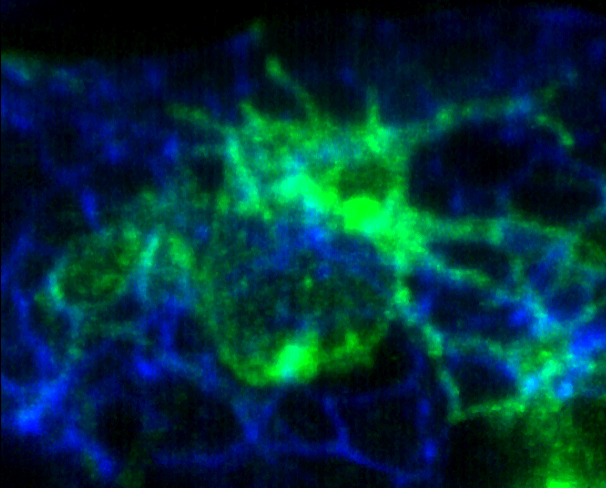

Yes, more than once. I love images in real time. One in particular comes to mind, from my years as a postdoc. It was a bit unexpected: it was one of those things that one expects but one knows deep inside that it’s unlikely, experimentally speaking. We were interested in using some zebrafish mutants which have alterations in apico-basal polarity, specifically in the retina, whereby neurons were found in unexpected places and accumulated differently, because there was a general disorganization. The initial question in my postdoc was how, in vivo, neurons orient themselves to decide its polarization: how is an axon generated at a specific moment of time, and how this axon moves in the right direction. In vitro this is a bit of an artificial situation, so we were interested to see this in vivo. We wanted to know what would happen with the neurons in these zebrafish mutants, where we knew signaling governing polarity was disrupted. Do they form the axon in a different way, or a different direction? The first mutant I went to check, expressed GFP in these neurons of the retina in particular, and the first time I went to the confocal, I made a movie, and saw a neuron that started to extend a projection from the apical side, growing into a different direction to the expected one. This time I didn’t want to believe this was true. I treated it as an artifact, but it turned out to be true. We were able to separate signalling for orientation and polarization as a result.

One has to make the most out of these moments as a PhD student and postdoc to enjoy this to the fullest. As a PI you will have less time. It’s been a while since I am in the lab but I still join my students to the microscope – of course without stealing the merit and happiness from them. But as a PI you are swallowed by administrative tasks, and these moments are harder and harder.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Uruguayan scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

In terms of infrastructure for microscopy, perhaps we still don’t have the latest technologies here. It is clear that any student loving microscopy might have at a point to go abroad.

Other than this, as a microscopist, you have to familiarize yourself perfectly with the principles of optics and light and microscopy, and with the equipment. Make sure you understand really well all the aspects of microscopy and micrography: There are a bunch of tricks to take excellent images, and if you don’t learn this, it’s not great. And spend a lot of time with the equipment – knowledge comes from practice. And then from using (and understanding well) basic microscopes, increase the complexity.

As a scientist, try to take advantage of a very broad education when it comes to Biology. Eventually you will be able to specialize (and it’s almost impossible not to). While in the lab, learn a lot of techniques, especially at the beginning of your career. Gain expertise on a large amount of tools – this takes time, but it is essential for your next steps as a scientist. An Uruguayan scientist who had a significant impact in my way of thinking in this respect, is Dr. Claudio Stern – currently in the UK at UCL. He came to Uruguay to give a course when I was a MSc student, and he told us that the most important thing for a scientist is to be able to find one’s question of interest. “What do you want to know?” Once you identify the question, and this question is clear, you are half-way along the way in your career. Then you have to find the methods and tools to answer this question. I find that for this, all your education and training is essential. Even if you personally don’t know all the techniques (because this is impossible), at least know they exist and what they can do to answer your questions. And don’t be afraid to jump across technologies, otherwise one risks becoming a ‘one-trick-pony’. This is dangerous.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Uruguay, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

Uruguay is a small country in terms of population, but also economic power. We have a good quality of life, but the economy is small, so it’s hard to reach critical masses. Thinking of science, this impacts us in terms of reaching enough numbers of scientists to cover all areas and have versatile expertise. This is one of the problems that Uruguay has, but which we have to face and overcome. We have been improving a lot, but it’s cyclical. The biggest challenge is that successive governments should have a constant commitment to science and development in the country. Beyond the internal challenges, sometimes they come from outside, as is the case of the pandemic.

In terms of microscopy, we have few centres of research. Our capacity for training researchers is enormous, but it’s far beyond what the country can retain in higher positions. So trained scientists either leave the country or leave science, which is very sad. So even if we grow in terms of locations dedicated to science, it’s so far not enough to host all the researchers we produce. I am certain that the work of Leonel Malacrida now represents a new turn in the tide of microscopy in Uruguay.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Uruguay a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

Historically, we have long standing work in neurosciences, in biochemistry and chemistry – these are very strong topics in Uruguay. The same is true in terms of parasitology, despite the fact that parasitic diseases are no longer a huge burden in our country. In terms of the country what I love most is our beaches. We are very few, and so you can go in the middle of summer to beautiful beaches, and find no one. This is very rare to find in the vicinity of main cities. We don’t have mountains (contrary to pretty much the rest of Latin America), but we have fields and a lot of very nice natural resources.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)