An interview with Luciano Masullo

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 6 September 2022

MiniBio: Dr. Luciano Masullo is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie postdoctoral fellow at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Munich, Germany, where he works at the interface of super-resolution microscopy and bionanotechnology in the group of Dr. Ralf Jungmann. He did his Licenciate degree (~ BSc + MSc) and PhD in Physics at the University of Buenos Aires, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He conducted his PhD research under the supervision of Dr. Fernando Stefani at the Center for Bionanoscience Research (CIBION). During this time, he was a visiting scientist in the lab of Dr. Ilaria Testa at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) in Stockholm, where he worked on super-resolution live-cell imaging by RESOLFT nanoscopy. Prior to this he conducted undergraduate research at the University of Buenos Aires, in the lab of Dr. Hernán Grecco, where he first entered the field of microscopy.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

This is an interesting question because in my case it’s atypical. Many scientists remember that when they were children they would put apart the radio or the TV to see how it works. I never did this. However, when I was a child I was interested in knowledge in general. I used to study maps and learn each country’s capital city, and other geographical details pertaining to each. As an adolescent I used to love History and Mathematics. During high school my inclinations about what degree to study, were History, Philosophy, or Mathematics. Later I realized pure Mathematics would be too much for me. And then I discovered the possibility of studying engineering, also considering the job prospects afterwards. One hears a lot of comments about this at the end of high school: that with a scientific career you will struggle making ends meet and so it’s not a career worth studying. So I joined a BSc in Engineering, and the first year is common core for Science and Engineering. That year I realized, because of my professors, that I really liked Physics. I started reading a lot about Physics: quantum physics, relativity, astrophysics. It was then that I decided that I really wanted to learn more about this general topic. Moreover, in my family there are no scientists, and I had no friends who were scientists. During this first year, I had a chance to speak to some scientists, and I realized one could make a living from science, and that it was not absolutely necessary to go abroad to succeed. So this is what encouraged me to continue in this track. Only much later on I would become interested in microscopy.

I actually started studying Philosophy in parallel with Physics because as you know, when you’re 19 years old you have huge amounts of energy. But after 1 year I didn’t continue because I realized that doing both degrees in parallel would be exhausting. Moreover, I realized after talking to various people that perhaps I wouldn’t love the career as a Historian or a Philosopher doing research, because it’s a very lonely job. I think this was a good choice. I would have struggled working mostly alone in a library. One thing I enjoy a lot from the natural sciences is teamwork and collaborations, and working in a lab full of people. But in terms of interest, I was interested (and I still am!) in both, the humanities and the natural sciences.

You have a career-long involvement in cell biology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose these paths?

I am always trying to learn Cell Biology – it’s always in collaboration with biologists. I am always very humble when I speak to Biologists, because I know very little about the subject compared to them. Most of what I know about Biology is due to the collaborations I did in interdisciplinary teams. I find Biology fascinating but it’s not my goal to become a Biologist though. My ‘entry’ into Biology was sort of by chance. What I did like from the beginning was Optics. From the first subject I had in Physics, I knew I was in love with mirrors, lenses, spectra, lasers, diffraction and so on. I loved all this. Later we had a lab of Modern Physics, with quantum physics, photons, detectors, and I realized I also loved this. The degree of Physics in Argentina is 6 years, but it is a combo that in other places would be BSc + MSc degrees. In Argentina, in the fifth year, we do a full practical project. I wanted to do my practical project in a lab of quantum optics but there were no vacancies. By chance I met a newly appointed professor that had just come back from several years working in Germany, called Hernán Grecco, who was not well known among the students because he had just come back and hadn’t yet taught any lectures. But I met him by chance and he told me he was looking for students. I found the topics he wanted to work on very interesting – he wanted to use light-field microscopy (a one-shot 3D method) and I found this very exciting. So I joined his lab, and I found the microscopic world fascinating. There I saw cells under a fluorescent microscope for the first time, and I built a light microscope prototype for the first time too. Then, I decided to go one step further. I knew that Dr. Fernando Stefani was doing super-resolution, and I spoke with him about doing my MSc thesis, and later, my PhD. But it’s funny to think about the serendipity factor: if the lab I applied to work on quantum optics had had a vacancy, perhaps now I would be working on that instead of microscopy. I think I am lucky though to be working on microscopy, but it happened by chance.

My interest for Astronomy is yet another thing: I applied for a fellowship to work full time on an Astrophysics project, but I didn’t get it. If the fellowship application had been successful, I would have done my MSc thesis, and then maybe my PhD on this topic. Again, serendipity: I could today be working on Astrophysics. Today I realize Astrophysics and Microscopy have a lot in common: they both use extensively optical systems and light signals (photons) to study natural phenomena. One thing I like a lot about Microscopy, which perhaps is missing from Astrophysics, is that one can still build one’s own optical systems. In Astronomy everything is so complex and expensive that most of a student’s work would be computer and design based, and perhaps about making a small piece of the telescope, but you never get to touch a mirror or a detector or something like this. The level of specialization is very high. In microscopy one cannot be an expert on every little piece, but you still get to see the big picture. Your system/setup easily becomes your baby!

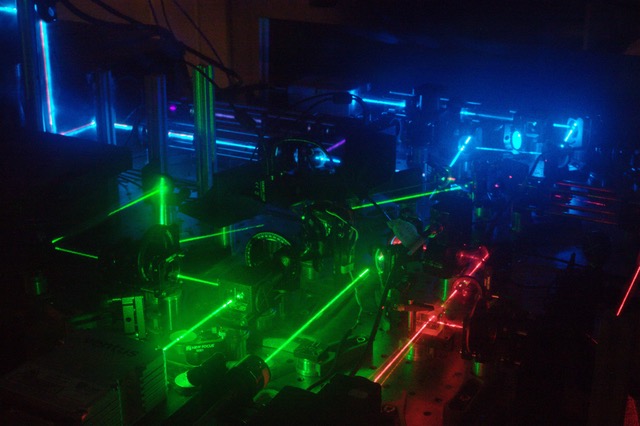

About my ‘entry’ into the field of super-resolution microscopy, this happened because Fernando Stefani started working on this in Argentina, and his former PhD students (Dr. Martín Bordenave and Dr. Federico Barabas) built STED and STORM microscopes. I worked during my MSc and beginning of my PhD on those systems – simple modifications and expansions, things like adding a component or so, and aligning and measuring in the microscopes within the scope of collaborations. Later on, I went for a year to the lab of Dr. Ilaria Testa in Stockholm, who is an alumnus from the lab of Stefan Hell, and is a specialist in a type of STED microscopy called RESOLFT, which uses photoconvertible proteins and is especially well-suited for live-cell studies. I learned a lot during this year and it was awesome. I worked on a parallelized version of RESOLFT to capture wider fields of view with very high sensitivity and resolution. It was similar to SIM to some extent, but always working on the real space (scanning and adding up intensities), rather than the Fourier space. Then I came back to Argentina for the second part of my PhD, and worked together with Fernando Stefani on MINFLUX, which consists of molecule localization using structured beams (with doughnuts). The last two years of my PhD I worked on two projects related to these techniques. Now as a postdoc I work with DNA-PAINT – which allows single molecule localization using the transient binding of DNA strands – in Dr. Ralf Jungmann’s team, combining my expertise in optics hardware with the impressive expertise they have here on DNA nanotechnology and development of labeling strategies. So this has been my tour around super-resolution. A curious thing that happens sometimes is that some people assume I have extensive experience using commercial setups. I have hardly ever worked with commercial setups – all the microscopes I’ve worked with were home-made. My opinion – and the opinion of many people in the field, is that the performance you can get with home-made microscopes is better than the performance you get from commercial microscopes. The problem is the level of robustness and user-friendliness: in home-made setups perhaps every week or every month you have to align lasers, fibers, mirrors, etc. But if you know how to do this, you can get amazing results. I would love if this (open-source microscopes) could be better developed in our region, and if there could be stronger networks and more collaborations in general among Latin-American microscopists.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Argentina, from your education years?

I think there are 2 or 3 things that are super important. Higher education in Argentina is very good. It is also public and free, students pay no fees. It has a great level, even compared to other first world countries where perhaps teaching (especially to undergraduate students) is seen as a burden that everyone runs away from. In Argentina a lot of importance and effort is given to teaching. I have the feeling that in wealthier countries, teaching doesn’t have so much relevance compared to research. In Argentina, students are motivated to go to the greatest depths of a given topic. You’re encouraged to ask ‘why?’ and to really submerge yourself in your topic. I think this is super important for researchers. It’s the only way to then be able to generate your own questions and hypotheses. I feel I had excellent teachers! They had a fantastic attitude and really encouraged us. I experienced the same during my PhD – Fernando always encouraged me to truly understand key concepts and key questions: to the greatest depth and very rigorously. He focuses more on this rather than getting quick results. I think this ‘quick results’ attitude can be deleterious to a PhD. The whole point is to reach the frontier of knowledge and push it by truly understanding a topic. This is sometimes incompatible with quick results. I apply this style I learned during my PhD, and it’s essential for me. I think this is also the way to actually enjoy research in science.

In Argentina, scientists typically have two jobs – the one of researcher and the one of ‘professor’ which involves teaching. In general I think the passion that teachers/lecturers have, makes all the difference. We might not have the huge amount of resources that countries in the Global North have, but I also feel that because of this, you gain other skills. This includes careful experiment design, and a true understanding of all the concepts and components. However, the luck of funding many times also means that in terms of output we go more slowly, and it’s more difficult to do science.

Once you chose microscopy as a profession or main discipline, can you expand more about how your career has progressed in this line?

My PhD became a bit longer because of the COVID pandemic, instead of defending my PhD in December 2020, I defended in August 2021. Since October 2021 I am in the group of Ralf Jungmann in the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Munich, Germany. I will stay here for at least another 2 years. I got a Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellowship, which will start in January 2023 and I am very excited about it. The lab is great, and Ralf is a great group leader. The group is super inter-disciplinary – there are Chemists, Biologists, Biochemists, Physicists, and Ralf really creates an atmosphere in which we can communicate, collaborate and learn from each other despite coming from different fields. We all learn a common language and common basis. So this has been super interesting and enriching. I am still working on super-resolution here, but now I am learning much more about biochemistry, protein science, DNA nanotechnology, and contributing in microscopy. We are pursuing really exciting projects both from the method development and from the biological applications point of view.

During my PhD, besides of the work I did in Ilaria’s lab in Stockholm, I also visited the lab of Dr. Philip Tinnefeld in Munich. This gave me a good view on how it is to do science outside Argentina, but only now I am pursuing a long-term research period abroad.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a researcher involved in microscopy?

I never do the same every day, and this is something I love about science. It’s never monotonous. Ralf was looking for people who could design and build novel microscopes -his lab had previously mainly focused on probes and software development. So, I arrived and immediately started designing and building microscopes. A part of my every day job is to design and build optical systems, and then benchmark them. I am also working on generating new data analysis methods. More recently I have also started to work with PhD students, supervising and helping them design experiments and interpret results. I think I feel comfortable with this role because of my education in Argentina: one has to teach since early on in one’s career, so I already had experience in mentoring. Then, I also do measurements for my projects, on cells, and using DNA origami. I think these are the main things I do on a daily basis. But this depends on the day – some days I am all day in the lab aligning optics, some days measuring and other days I sit all day at the computer analyzing data. In terms of data analysis, I did some quantitative imaging in neuronal structures (actin-spectrin rings, which are distributed with a certain periodicity along the membrane of axons and dendrites). The image analysis pipelines can be used for other structures too. In this project I learned a lot about basic tools regarding data analysis. And this was very helpful later on, for all the projects I have worked on after this. Moreover, I really like statistics, and have worked with that and modeling and simulations. So, I do a bit of this in terms of data analysis – temporal series, single molecule localization, finding clusters, minimum distances between molecules, and so on. A bit of everything. But I wouldn’t say I am an expert in any particular type of algorithms.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Argentina?

Zero. Not really, and this is a pity. I had a lot of interactions with European groups. Or within Argentina, with groups focused in Optics. I know the groups that do microscopy in Argentina, but much more from the Physics point of view. From the rest of Latin America, not so much at all. Perhaps from Twitter I’ve recently heard about Leonel Malacrida’s work in Uruguay who is doing great things both in research and LABI. From Mexico, Brazil and Chile I know the name of some labs here and there, and from the rest of Latin America, not at all.

I think it’s a common “failure” in the sense that we sometimes look abroad (in the Global North) for collaborations instead of the neighbours. For instance, Montevideo is 2 hours away from Buenos Aires – it would be possible to interact a lot more. Mexico is not close in terms of distance, but I’m sure we could find ways of collaborating more. An issue in Latin America is that all our countries are enormous, and the distances between them even more so. We’re talking about many hours on an airplane to get to most countries so… this doesn’t play in our favour. Compare that to Europe, where you take a train and in a few hours you’re in a different country.

We had a collaboration with scientists from Cordoba, which is relatively close to Buenos Aires within Argentina, and that’s already 8-10 hours by car. So even then it was not so easy to send samples: you had to be careful about when you send them and make sure there’s enough dry ice and so on.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as an Argentinian researcher, working abroad?

To be honest, not really. Not because of being Argentinian. Both in Sweden and Germany I felt very welcome. I never felt any discrimination or racism. But I am aware I’m a highly qualified white man, so this is perhaps me speaking from a privileged point of view. Moreover, because of my grandparents, I have an Italian passport, so in terms of immigration permits I didn’t have any issues. And in terms of science, I felt that my Argentinian education was very strong. I didn’t feel I was behind others in terms of knowledge or skill. Of course, immigration is always difficult – in the first few months you have to sort out all the bureaucracies, social security, and so on. But I guess this is normal. And in terms of language, I also didn’t struggle. In Sweden everyone speaks English perfectly, and in Germany you can also get along very well with English. Moreover, at the Max Planck Institute, the community is very international. I know other colleagues who went perhaps to a smaller University, and found that the level of internationalization is much lower. In our lab for instance, we’re maybe 50% foreigners, and the language at work is English. Anyway, I am slowly learning German, I want to be able to communicate decently in this language.

However, I haven’t been abroad for very long. I still don’t face the issue of missing home and my family too much. Besides, we’re fortunate that we can visit one another – my parents are coming soon, and I’ll go home at the end of the year. So, let’s see what the future holds.

Who are your scientific role models (both Argentinian and foreign)?

I think I have many favourite scientists that I first knew from papers and then saw at conferences. I really admire scientists who do honest and transparent science. Those who have very solid data and explain in the clearest way possible what their findings are and how they achieved them. Those that don’t try to oversell the findings, and that really go deep in their analysis and research questions. I really like this. I also admire scientists who are good teachers – who love learning and grasp the big picture.

And then, I don’t know if I would call them role models, but I admire those who can communicate science and generate passion for science. For instance, science books that I really liked, were written by a physicist called David Griffiths. When I finished my studies, I emailed him telling him I loved his books, and he replied it was lovely to read this. These were books that strongly inspired me as a scientist.

Then in the field of microscopy, I find the work done by Jörg Enderlein extremely inspiring. All the winners of the Nobel Prize for super-resolution microscopy are also amazing- Eric Betzig, Stefan W. Hell, William E. Moerner – their research is spectacular and ground-breaking. One thing I found admirable of W. E. Moerner is that when I saw him at a conference in Berlin, I found him to be very humble: he stayed for the entire conference, he asked constructive questions in each talk, he went to every poster of every student and spoke with each student for a few minutes. I gave a 10-minute talk (my first talk at a “big” conference) and he came to talk to me afterwards to congratulate me. In his own lecture, in each slide he showed and credited the PhD students and postdocs who had done the work. When the Chair of the session introduced him, he said that his first priority are the lectures he teaches at Stanford – that he doesn’t accept invitations to give talks or conferences if they are in the middle of the semester when he has to teach. I really admire the human side of scientists. I think this is very important – sometimes just as important as the scientific achievements. When he came to speak with me, I think my legs were trembling when he told me ‘what a nice talk’. I was a young PhD student coming from Argentina and there it is this scientist who was the first to observe an individual molecule by fluorescence shaking my hand and appreciating my work. I also have to mention the work of Andrew York – he is a microscopist whose work and open source philosophy is something I admire a lot. I find his way of doing science extremely innovative and inspiring. This is just to mention some among the dozens of outstanding scientists in the field. There are a lot of scientists doing amazing microscopy, there’s a lot of innovation going on.

In Argentina, Hernán Grecco had a huge impact – he was the first to introduce me into the field of microscopy, and then of course Fernando Stefani – I learned a lot from him how to think about science, and from him personally. When I started, Hernán gave us – me and another student – a huge amount of independence. We didn’t know anything and he gave us the task of building a microscope. He draw it on a blackboard, and then sent us away to work on it. It was an intense learning experience. And then with Fernando I grew up as a scientist and learnt how to design and conduct research, from brainstorming ideas, to theoretical designs, experimental implementations and paper writing. The other person who had a huge impact on me was Ilaria Testa: not only she taught me a lot about optics and microscopy when I was in Sweden, but she also helped me acquire confidence in the work I was doing. We discussed a lot of ideas together. At some point I came up with an out-of-the-box solution for one of the projects and she said ‘let’s give it a try’. This idea wasn’t planned, it might not have worked, but we bought all the material, and we did it. I was a 1st year PhD student and she trusted me enough to do this. What I learned in Sweden was truly valuable. All in all, these three scientists really left a mark in the way I do science.

Finally, in my family there has always been the philosophy that studying hard and learning was important for progressing. My family comes from poor migrants from Spain and Italy, who progressed due to the public education of Argentina. So for my family and particularly my parents, education and knowledge has always been very valuable. This curiosity for learning new things is something I experienced since I was young, and I think this has been vital for my career as a scientist.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Argentina, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

When I compare it to what I have seen in Germany, I was surprised about the level of awareness that we have in Argentina, regarding gender (im)balance. There are many Physics full professors in Argentina (in relative terms of course). Comparatively, here in Munich you barely hear about female full professors in the field. This was shocking. In Argentina, the number of women professors is much higher, and I think this is really important – especially for young women, but also for young men – it’s important for everyone to see that this is both, possible, and totally normal- to see women in positions of power, and as respected, successful academics. I think also Argentina saw in recent years, very strong feminist movements, and so I feel awareness is much higher.

However, in Argentina then the “glass ceiling” occurs: in natural sciences PhDs, the ratio of men to women is around 50:50, but then a disaster happens as one progresses in one’s career: in positions of power it’s mostly men. This is very serious, and it’s something we must change. There’s a lot to be done to truly eliminate the glass ceiling. But it’s my impression that we’re ahead of what I’ve seen in some European countries. But I must say that this is just an impression, I haven’t done careful research on this.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

I love fluorescence microscopy. Since the first time I saw something by fluorescence, there was something aesthetic and artistic about microscopy. There’s this beautiful side to what we do on a daily basis. I believe this is actually not a minor point. Then, I always worked on super-resolution, which has a lot of Physics involved. In particular I have worked on single-molecule analysis, and this for me is amazing. Can you imagine? We are looking at one single molecule at a time! It’s fantastic. It always amazes me when I think about it. Another thing I loved is to work with living cells. Combining live cells with super-resolution as in RESOLFT is very challenging, but the insight you can gain in biological processes is incredible.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

I can think of three. In terms of Cell Biology, we were studying the spectrin rings in neurons in a neurodegenerative treatment, and we were the first to see the ring distribution in damaged neurons. This was amazing. But I think since I have focused on developing methods, my eureka moments are more related to the method working! I’ll say something very nerdy, but in Star Wars Episode I, there’s a moment when Anakin gets a spaceship to work, and he shouts ‘It’s working! It’s working!’ That’s how I feel. In Sweden, this happened. Once I was walking towards the lab, and I suddenly had a very important idea to solve a problem (the one I mentioned before) and once you see the answer you can’t stop thinking about it, I even walked faster to the lab that day, almost running. After implementing the idea into the optical system, I was fearful that my idea wouldn’t work because RESOLFT is a complicated system. Unlike STED, there are many parameters to consider regarding the photophysics of the fluorescent proteins. But the idea worked. After some frustrating moments, we saw an image of the cytoskeletal protein vimentin at 60 nm resolution, and I was super excited. Ilaria came to the lab and I could see the happiness in her face as she saw the results. He gave her approval and we started to outline the paper on this project that same week. The other eureka moment was also in my PhD – I had an idea of how to make MINFLUX, but in a much, much simpler way. I had this idea that we could try it in a conventional confocal microscope, and I told about it to my colleague and friend, Dr. Alan Szalai who was a postdoc in the lab at the time. He was excited about the idea and we both went to the lab, we changed a few things in the microscope, and we made it work! It was the first time that I experienced having an idea, quickly testing it, and it works straight away! I think these are my favourite eureka moments 🙂

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Argentinian scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

I think the first thing I would say, especially in Argentina, and perhaps in the rest of Latin America -is that it’s possible to become a scientist. I see that in Germany it’s very natural to be a scientist – it is highly respected, but it doesn’t surprise anyone. In Argentina, when I started studying, it was very uncommon to study science, especially if you come from outside the scientific pedigree. Everyone tells you you’ll starve to death, or won’t get a job. This is not true. You can live from a science job, both if you want to do academic science or go to industry. I loved every second of my education as a scientist. I have friends who studied Business Administration, or something along these lines, who say they have zero interest in the lectures they took. It is true that science is a difficult career, the salaries are low, but my opinion is that living in Latin America is more difficult than living in Europe overall, it’s not something specific of doing research. Within these difficulties, you can be a successful scientist in Argentina.

In terms of specific advice in the field of microscopy, I would say: invest the years of your PhD in understanding key concepts and your topic really well. Don’t get pressured to do 1000 experiments or publish papers fast. Dedicate years and focus in order to learn and grasp the concepts and the basics of science. I think this is vital.

In Argentina, outside basic research, I have many colleagues who studied Physics and now work at companies doing data science, or technological developments and earn 3x what a basic research scientist does, that is also always a possibility. There is plenty of options. All in all, studying science won’t give you luxury, but it’s definitely a career you can make a living from.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Argentina, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think there are many good scientists in Argentina, but the problem comes with long-term policies. They don’t exist. When it comes to government policies related to science, there is little to no certainty and a lot of ups and downs. However, the problem doesn’t lie in the human resources – these are excellent. If we had a sustained investment in science, in a manner that was constant and predictable, even if it wasn’t as big as in the USA or Europe, I think we could do amazing things in our country. In the topic of microscopy, I’m excited about what the future holds and the capacity of the country for great science. We have 3 Nobel Prize Laureates in the field of Molecular Biology in Argentina and a pioneer in fluorescence studies, Gregorio Weber – education has been and still is really good. In terms of advanced microscopy, however, we have very little. There are 3-4 groups that do significant developments in fluorescence microscopy. There is a lot of space for growth and improvement. One of my dreams, now that I am abroad, is to be able to one day come back to Argentina and do good science. In terms of microscopy, I think there’s a lot of potential. I’m not in a hurry to go back right now, but I hope to be able to go back at some point and have a good chance to contribute to science and development in Argentina. I think a stronger network between the microscopy community in Latin America would be a huge plus. I think it would help everyone progress.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Argentina a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

From a tourist point of view, we have amazing sceneries! I sometimes get asked in Germany ‘what’s the weather like in Argentina?’. This is a difficult question – Argentina is huge (especially long) and we have all sorts of climates. The Northwest is a desert, the Northeast is a jungle, the centre is cold – we have mountains, Buenos Aires is a plain, and the South of Argentina looks more like Sweden or Norway, we also have the southernmost city in the world. There are wonderful landscapes and in terms of nature and biodiversity, the country is very rich. Maybe it’s something common to all of Latin America – the landscapes and natural beauty is a highlight. And in Argentina (and perhaps common to Latin America in general) people are very kind and very friendly. You feel welcome, which is different perhaps to other cultures. In Argentina people will invite you to their home, they will make an ‘asado’ (grilled meat) and the friendship bonds are very strong. My city, Buenos Aires is perhaps a ‘quilombo’ (a chaos), but it has a vibrant cultural life (there’s theater, dance, music, it’s always getting renovated) and a unique identity that I love. And then there’s the amazing food… luckily for me I can get Argentinian meat in Munich so you can get great asado in my house as well 🙂

(3 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)

(3 votes, average: 1.00 out of 1)