An interview with Pablo J. Sáez

Posted by Mariana De Niz, on 17 January 2023

MiniBio: Dr. Pablo J. Sáez is a Professor at UniversitätsKlinikum Eppendorf (UKE), in Hamburg, Germany since 2020, where him and his lab study single and collective cell migration with a focus on immune cells. He was born in Chile and did his early career there. He did his BSc, MSc and PhD at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (UC), under the supervision of Dr. Juan Carlos Sáez where he first came into contact with the microscopic world at professional level and worked on ion channels and calcium signal during immune cell migration. He then worked with Dr. Marcelo Farías at the Centro de Investigaciones Médicas (CIM), Faculty of Medicine of UC studying ER stress responses and foetal programming during maternal obesity. Later he joined the lab of Dr. Ana Maria Lennon-Duménil at Institut Curie in France, where he focused on B cell biology. Later he went on to work with Pablo Vargas’ Motile team in the lab of Matthieu Piel –at Institut Curie, Institut Pierre-Gilles de Gennes where he integrated microfluidics to study immune cell migration. During his career, Pablo has had a long-standing interest in immune cells, and in microscopy, which he uses extensively to explore cell migration in the context of cancer and other pathophysiological phenomena.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

When I was a child I actually wanted to be a pilot because I love to fly. However, at some point due to a respiratory illness I underwent an ears and nose surgery. The doctors explained to me that as a result of this surgery I had a high susceptibility to pressure building up in the ear canal, for instance I love scuba diving, but I can’t dive very deep because of this. So my mum told me that due to all this I wouldn’t be able to become a pilot. Around the same years, at school we were doing experiments such as observing root development in carrots. My mum recalls that I had 3 carrots, which I placed in a glass with water, water + sugar, or water + salt, respectively. At that point she realized I was very curious about understanding how the world around us works. As a result of this, one of my uncles gave me as a gift, a chemistry kit, where you can see elements interacting with one another and changing colour. I only did one experiment. When my family asked me why I stopped using it, they recall that I said that “I am keeping it for my own lab when I’ll be a grownup”. Around those years (I must have been 7 years old) there was also a TV series called “Erase una vez la vida” (translated as Once upon a Time), which described how the universe of our cells works. I loved this TV show. Then, when I was around 10 years old, a cousin showed me his light microscope and we observed some ants, worms, leaves and flowers, enabling me to discover the microscopic world, and to realize that there was indeed possible to explore a world beyond what was observable by the naked eye. During high school in Chile, one has to choose an area which one will pursue in University. At the time I wanted to study Medicine so I could later become a researcher in the areas of applied physiology and human pathology. However, in my high school, the Liceo José Victorino Lastarria, there was a teacher called no other, Ana Sara Edwards Karlström. She was Chilean-German and had a very peculiar way of teaching, and for this reason many students found her classes very difficult. She had a very practical approach. Liceo Lastarria is a traditional and renowned school in Chile, which had very good equipment in comparison to other public schools at the time. We had several microscopes, and because I was always excited to use the microscopes she brought me some samples so I could practice. I liked neuroscience and the study of the mind, so I asked her for brain tissue sections, and she brought me some with classical staining. I think I almost fell asleep – I mean, I found it a beautiful, fascinating structure, but also super boring, because everything was static, nothing like a living brain. Then, to study photosynthesis, instead of learning about signalling pathways from the book, she brought some algae and we put them under water, some exposed to sunlight and others in the shadow. The idea was to have a look under the microscope to see what was going on in both conditions. When we looked at the samples exposed to sunlight we could see bubbles which indeed was linked to photosynthesis, but I was immediately distracted because I saw something moving in the sample, which turned out to be an amoeba. Since then, I became fascinated with cell motility, and still am to this day. My teacher asked me to follow the amoeba, and not lose focus, as the microscope was coupled to a TV so the rest of the class could also see it. I managed to do this despite the mixture of jokes and cheers from my other 44 classmates. I started to study, under her guidance, several samples of “dirty water” that I would keep at home for days to let microorganisms grow. She eventually asked me what I wanted to study at University level and I said Medicine and I told her the plan I had in mind to later become a researcher. She told me there was another path to do the same things, and re-directed me to think about the scientific careers like Biology or Biochemistry. That’s how I ended up studying Biology. Nowadays, what inspires me to be a scientist is my wife, children and my family, friends and the great group of young researchers that compose my lab.

You have a career-long involvement in cell biology and microscopy. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired you to choose this path?

I enrolled in a BSc in Biology at Universidad Católica. We had lots of lab practical courses including one to obtain sea urchin oocytes and sperm samples to observe fertilization. We had heard about the subject of Developmental Biology by our main professor who used to invite some guest professors. One of these was a Chilean world-renowned scientist, Roberto Mayor. The experiments were amazing as we were even able to observe several rounds of cell division in real time under the microscope. I recall talking absolutely amazed about these observations to my classmates and friends Alejandro Montenegro and Tania Timmermann, while observing these cell divisions live! This is what drove me into the field of cell biology. Although prior to this I was also interested in other macro-processes like organ physiology, it was around this time that the field of Cell Biology became my world. As a result of this interest, I started working in a lab a bit prematurely, because usually lab internships began around the 3rd or 4th year of the degree, but I started earlier at 19 years of age. I joined the laboratory of Juan Carlos Sáez (we share the same last name but we are not related! It’s just a coincidence) at the Physiology Department to work on cellular physiology, mainly using microscopy, I did my bachelor thesis there on the role of cell communication and calcium signalling of brain macrophages, microglia. Then, I did my MSc and PhD, which is combined in Chile, in the same lab, studying the role of danger signals and ion channels during immune cell migration. So, I remained in the same lab for more than 7 years and made long-lasting friendships and collaborations, including some which who I regularly talk, such as Kenji Shoji. At the time we used to do a system of peer review and so colleagues from the PhD program would ask you to review their project. That’s how I came into the organelles world, when Elisa Balboa asked me to review her project about mitochondria in a lysosomal storage disease. My first impression was that it will be a biochemistry-signalling manuscript, not my cup of tea. However, I was completely wrong and it was incredible to see the pictures of mitochondrial dynamics. Since then I got hooked by the organelles. That’s why after finishing my PhD I moved to the Faculty of Medicine in the same University – just one building down the road, to work in the team of Marcelo Farías, hosted in the lab of Luis Sobrevia. We studied foetal programming during maternal obesity, and found ER-stress measured in the umbilical cord. Marcelo is a medical doctor who had done his PhD in Biomedicine, so he was extremely knowledgeable and helpful during my immersion in this field. I contributed with my knowledge in cell biology and we started together to explore organelle function. It was a short time but had the chance to work with great scientists: Fransciso Westermeier and Roberto Villalobos. Moreover, I was in charge of the team and it was a great experience to feel what it was like to be a team leader. I even started new collaborations with people from my previous departments, such as Gareth Owen. I then went as a postdoc to the lab of Ana María Lennon-Duménil at Institut Curie in France. At this point I changed fields a little bit. I had always worked on immune cells, especially dendritic cells and T cells. During my PhD I did an internship at Ana María’s lab – thanks to an EMBO fellowship to study cell migration. When I came back as a postdoc, Ana María asked me to continue the project of a colleague of mine (also interviewed in this series – Maria Isabel Yuseff) focusing on B cell activation. At the beginning I wasn’t particularly fascinated, but eventually it was a good decision and proved to be fruitful – I learned a lot about the cytoskeleton, and organelles during cell polarization. In my PhD I had focused on cell migration, calcium signalling, and inter-cellular communication, but I had not touched on the topic of intra-cellular communication, and this project was a good chance for that.. Organelles are truly a world of their own, especially when it comes to their roles in intra-cellular communication! After my time at Institut Curie, I did a second postdoc. During my first postdoc, I met a Chilean scientist, Pablo Vargas, who started a small team within the lab of Matthieu Piel – he was a collaborator of Ana Maria and had great expertise on physical models of the cell, and microfluidics. During this time I learned a lot about physical modelling of cell migration. This lab is also at Institut Curie, at IPGG (Institut Pierre-Gilles de Gennes). IPGG is a rather interesting institute, because it brings together scientists studying microfluidics, regardless of their institute’s affiliation. I worked there until 2020 when I got my independent position as a PI, which is the position I now hold at UKE (Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf), in Hamburg, Germany. Thus, as you can see in my lab we do essentially a mixture of everything I have learned during my career [laughs].

So you established your lab in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. How was this experience?

It was a huge challenge to start a lab during a pandemic! Because this was additional to all the logistics of moving with my entire family – my wife and two children. We did it in the middle of the lockdown. The only reason why I was allowed to move during this time was that I was joining a medical institution. Otherwise we would have had to stay under lockdown in France. In terms of setting up the lab, it was extremely challenging. Because of the pandemic, we experienced major delays and shortages in all fronts. The problem is that now, 2.5 years on, the funding agencies and reviewers seem to have forgotten about the pandemic. So in the evaluations, they count these years as if they had been 100% productive, and as if these challenges and delays didn’t happen. The truth is of those 2.5 years, only the last one was more or less productive. Moreover, the way of doing science is very different in France and Germany, so one has to adapt to this – in France I was already used to a very dynamic collaborative environment. In Germany in my experience it has been slightly more difficult, also due to the situation triggered by the pandemic. Nevertheless, I received great support from my colleagues of the Department Jörg Heeren, and the chairman Andreas Guse. Both of them have been very helpful and generous. And as the pandemic-related restrictions have decreased, it has been easier to interact and collaborate with other colleagues, such as Maike Frye, Nicola Gagliani and the Virgilio Failla from the microscopy facility. Also, Hamburg is a very green city, proportional to the rain [laughs], and the quality of life is very high with a more relaxed rhythm of life than Paris, the world’s capital.

Can you tell us a bit about what you have found uniquely positive about becoming a researcher in Chile, from your education years?

I think the Chilean, and Latin, researchers are appreciated by scientific communities around the world. In South America, we are used to do a lot with very little. My PhD adviser promoted this a lot: “to squeeze the lemon to the maximum”. Since resources are limited, you have to make the most of it. We are encouraged, already as PhD students to go beyond the obvious next step, as this likely would be done faster somewhere else. At the time, we as graduate students, complained about how rigid the programme was – we had tests that lasted more than 7 hours and included lunch during the test. It was crazy! When I asked what the point of these tough tests was, my PhD adviser and director of the Physiology PhD program Juan Carlos Sáez told us the point was to learn to develop resilience and perseverance. That we should think about a later point in our careers as scientists when we would have to balance having a family, teaching classes, supervising students, doing research, and writing grants. He told us not to lose sight of this “big picture”, or underestimate the value of perseverance and resilience. That at the end of the day our scientific knowledge would be only one of the many factors to determine our success as scientists, and resilience and perseverance would become equally, if not more, decisive. There were many students who, half-way through the 7-hour test would start answering in a less detailed way due to the fatigue. The ones that stayed until the end got better marks but above all, acquired traits that I think later became useful in the scientific career. Overall, in Latin America in general – and in my case, Chile in particular, we are used to do a lot with very little, so when we do have access to more resources, we can increase our productivity and this becomes an advantage. Perhaps we don’t realize it while we are in Chile, but when we go abroad to countries where resources are more abundant, this becomes obvious. At the moment I have a visiting PhD student from Maria Isabel Yussefi’s lab, called Martina Alamo, who is experiencing this. In Chile one has to plan experiments very well, with little chances to repeat a failed experiment, abroad you have more chances.

Can you tell us a bit about your day-to-day work as a PI in Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf?

I have to teach a lot, so I have two types of routines: one routine is when I have to teach – I prepare the classes, and teach, and have little time to dedicate to the lab. When I don’t have to teach, my day starts with all the pending work including writing or reviewing papers, writing letters of recommendation, reading my student’s reports, respond to emails (and resolve as many as possible), and interact with my students. Regarding this last point, at Institut Curie I learned a supervision style of open doors, in which if any student had questions, they could ask their supervisor or other PIs at any time. I don’t know if this is the most time-efficient method, but it’s the one I implemented in my lab as PI. So my students can come to my office any time. Sometimes we go to the microscopes together – I have certainly kept my passion for doing microscopy myself, so I do this as often as I can. Then I usually have meetings with my international collaborators – this is usually later in the day because of our different time zones. Among my most important collaborators are Yamuna Krishnan and Nir Gov they are in Chicago and in Israel, respectively. After the meetings, sometimes I have to pick up my children from school, and so my day at the lab stops a bit earlier and several times resumes later at night. Otherwise, I usually spend time with my students doing planning, revisiting experimental protocols, finding out if they have experimental challenges and figuring out how we can best address those challenges, going through data and images of course. So, yes it looks like a busy day, but I love it.

Did you have many opportunities to interact with other Latin American groups, outside of Chile?

Yes, at Institut Curie in particular I was able to collaborate with many Latin American scientists. This is partly because there are a few Latin American group leaders there, like Ana María Lennon, Eliane Piaggio from Argentina, and Sebastian Amigorena who is French-Argentinian. There’s a nice Latin American community at Curie – “la banda quilombera”, including many Argentinians, but also Chileans and Brazilians in particular. There, I met many good collaborators with whom I have continued working to this day after many years. In particular I maintain collaboration with Catalina Lodillinsky, who now has a team in Argentina- her homeland. At UKE I’ve also met Latin American colleagues, like Victor Puelles, who is Peruvian-Australian and we collaborate regarding image analysis and super resolution microscopy. I think usually, when we Latin Americans live abroad, we tend to interact a lot – we share very strong cultural roots so it’s understandable. I also have a Chilean collaborator – Eliseo Eugenín, currently working in the USA. He did his PhD in the same lab where I did mine but we didn’t coincide time-wise. When I was still in Chile, I remember going to courses and workshops in Uruguay. The strongest collaborations were set with Argentinians and Uruguayans. But I have now lived abroad for over 10 years, so I have lost track of how networking in Chile is. However, I can imagine it has progressed a lot, and that initiatives such as Latin American Bioimaging will be key for networking and science progress, specifically in microscopy. It would be great to have something like EMBO in Latin America, yet the main thing missing are resources.

Have you ever faced any specific challenges as a Chilean researcher, working abroad?

I think the cultural clash at the beginning can be difficult. But this depends on where you work abroad. In cultural terms of the European countries, there are some with whom we have great cultural affinity including Italy, Portugal and Spain. Perhaps less so in France, but it’s a matter of giving it time to develop friendships. I have many good friends in France now. Languages are also a challenge of course. I now speak French but not yet German. At Institut Curie I met many Italian scientists and we bonded quickly. Another challenge for me is the weather and latitude differences! I find it very hard to live in places where it’s always dark and cold, unlike Chile’s central region. But I feel as a scientist it’s easier to become integrated with the professional community: a scientist in France is similar to a scientist in Chile or Germany in terms of the work we do. This integration is harder in other professions like Medicine or Law for example, where you need a major revalidation of your professional experience. As a scientist, a microscope in Japan works the same way as in Chile or elsewhere in the world. It feels we are in a bubble, professionally speaking However, there were some professional clashes that showed big differences between South America and Europe, for example that PhD students many times would have a contract that includes social security and health insurance, that there were strict regulations for the holidays everyone has available. This definitely needs to be improved in South America, in such a way that researchers at every level would be considered as any other worker. In terms of racism, I have witnessed it of course, but never felt it myself in a major way – except for perhaps the only time I can recall, when we were looking for a house in Paris and not being French drastically limited our chances.

Who are your scientific role models (both Chilean and foreign)?

There are a few main scientists I can think of. One is Francisco Varela, a Chilean neuroscientist who passed away back in 2001, but he proposed completely novel concepts such as autopoiesis, which has been key for the development of artificial intelligence. Then there is Ralph Steinman, a Canadian physician who discovered dendritic cells – I was lucky to see one of his presentations when he went to Chile around the time when I was a student. Then there is Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz – I find it surreal to be now colleagues and even be both members of the same editorial board. There’s also Gia Voeltz who is an expert in organelles, and Michael Berridge who was a leading expert in calcium signalling. I found great inspiration as a scientist reading the papers of these various scientists. And then someone mistakenly best known as an artist than a scientist, but whom is an all-time genius and has prevailed through the history of humanity, Leonardo da Vinci. His notebooks are a great source of inspiration to observe nature and learn from it, probably also the source of my affinity for scientific art. And of course after living in France, Louis Pasteur and Marie Sklodowska-Curie are of big inspiration.

What is your opinion on gender balance in Chile, given current initiatives in the country to address this important issue. How has this impacted your career?

I’m not really so aware of what is currently being done in Chile, but I imagine it has improved compared to how it was when I was a student. When I was there, the main differential was not at the point of recruitment – we were similar numbers of women and men in general. The problem arose in retention: the leaky pipeline whereby equal numbers of women enter the BSc degree, and similar proportions are maintained perhaps all the way to the PhD, but by the time one evaluated the gender balance in professor positions, the number of women is almost null. I think this is a serious problem. In the Department of Physiology, I never thought the gender misbalance was as extreme as in other departments or faculties perhaps. However, after reading the interview with Cristina Bertocchi I learned that the gap has increased rather than decreased – that is obviously not the right direction! Before I went abroad, I know that there were actions to promote gender balance, so it seems the system is doing something to address this. Also, a huge influence for the entire country was that we had the first woman president of Latin America, Michelle Bachelet. In terms of my own experience, the majority of staff members are women. I am trying to contribute to STEM and diversity. Out of 10 members, 2 are men, so for now recruitment is going well. But what I think of often is what to do to promote retention of this talent later on. At UKE, where I am currently at, there are very, very few women at PI level or above (less than 20%). I think there’s much to be done here now.

What is your favourite type of microscopy and why?

I love microscopy in general – both electron and optical, but perhaps the one I find most appealing right now is label-free microscopy techniques, such as holotomography. It’s my current obsession, but I have had great interest in other types of microscopy throughout my career – lattice light sheet for example. I find electron microscopy fascinating but the problem is that it’s static – and one of my biggest fascinations is cell motility, so I stick to live cell imaging.

What is the most extraordinary thing you have seen by microscopy? An eureka moment for you?

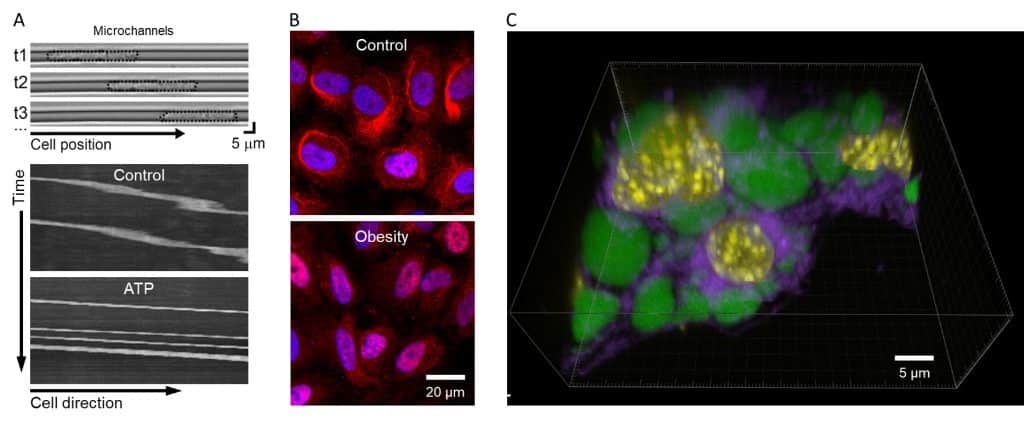

It’s difficult to pick a single moment! Perhaps I can choose three moments: one is when we observed that immune cells respond to extracellular ATP that acts as a danger signal (even in the absence of infection) by increasing their migration speed. I saw this fast migration using microchannels during my EMBO fellowship at Curie even before we could observe an increase in the speed using pathogenic signals, such as bacterial wall LPS. Then, observing this fast ATP-treated dendritic cells was an eureka moment. The second eureka moment happened two years later, when I was working with Marcelo Farías. We were investigating if endothelial cells from the umbilical cord from mothers with obesity were undergoing a cellular stress response, and we found ER-stress. I was at the confocal microscope and we observed an increased translocation of ATF6 (a main component of one of the ER stress pathways) to the nucleus, which was otherwise perinuclear in control conditions. I had an eureka moment when found that in all patients of maternal obesity, ATF6 was translocated to the nucleus. The third one was when David, a PhD of my lab, showed me a 3D visualization of adipocyte organelles including their lipid droplets. We don’t quite understand yet what is happening at a sub-cellular level, but the visualization alone is fascinating. Another two key moments related to microscopy were when Mathieu Maurin, a colleague at Curie, showed me how to write my own macros, this was certainly a breaking point. And finally when another colleague at IPGG-Curie, Mathieu Deygas managed to do chemotaxis in a hexagonal array of microchannels, the movies were so astonishing that we later acquired another ones and send it to the GFP image contest of ASCB-EMBO. We did not win the contest but when the movie was shown the whole room said “wow”, it gives me goose bumps to remember it.

What is an important piece of advice you would give to future Chilean scientists? and especially those specializing as microscopists?

My main advice would be to be bold and daring. Don’t be conservative when it comes to ideas and experimentation. Take risks – not just in terms of experiments but also going abroad, leaving the comfort zone. Science is about doing bets, and the bigger the bet, the bigger the price. There are people trying to improve the scientific community to which they will belong in a few years’ time. We’re trying to create a more ecological environment, less toxic than in previous generations. We’re working towards the goal that all genders, races, neurodiversity, and all forms of diversity, can belong. Where everyone can reach their maximum potential and can feel free to use their creativity. Here my interaction with my colleague Felicity Davis, now in Denmark has been instrumental. After talking to her many times I decided that every time I am invited to give talks at seminars I try to speak with the early career scientists to listen to them, try to answer their questions and hopefully provide advice. I have seen that many fears are shared across countries. I went to Denmark earlier this year, and also gave a virtual environment in Cordoba. You would imagine these students have almost no similarities in terms of culture, resources, and background, yet their fears were similar. So I would say, take risks. We are really working towards making the scientific community more welcoming. And I am sure once the new generations will reach positions of leadership, it will be up to them to continue the improvement, but at present, really, my advice is to dare to take steps away from the comfort zone. Another piece of advice is to not follow trends. If you follow trends you’ll join the mass in a field full of competition. There are scientific spaces which are less overwhelmed with competition. So, take the risk of finding new paths. It’s difficult to do this because communities grow together and one tends to follow the same path as others, but try not to do this and break paradigms. This is one of the reasons I love immunology. It breaks many paradigms.

Where do you see the future of science and microscopy heading over the next decade in Chile, and how do you hope to be part of this future?

I think the future of microscopy in Chile relies on networking – on forming a network that fosters collaborations and community science. I hope the Chilean community will interact more with the geographical neighbours too – and will establish much stronger networks than the ones currently existing. I hope to be able to contribute as a bridge to Chilean scientists that come abroad. To be a linker between the Chilean community and the European community where I currently belong, or the collaborators I have abroad, in Australia, Korea, Israel, and the USA. In terms of microscopy, I hope to contribute with my grain of salt to the community, exploring and developing new forms of microscopy, like label-free microscopy and image analysis.

Beyond science, what do you think makes Chile a special place to visit and go to as a scientist?

The biodiversity! There’s a Chilean scientific journalist, Andrea Obaid who called Chile a “natural lab” or in situ lab. If you like extreme weather, you can go to the north of Chile and see the desert. If you want to discover something completely new, you can go to see the flourished desert. Then there’s central Chile with the Andes, and the south, where many Chileans and Europeans love to go, to Patagonia and all the way to Antarctica. Many colleagues I know are fascinated by the natural diversity. Chile by being such a long country has a huge diversity – one can do snowboarding in the morning, take a car to cross the country across its width, and a few hours later do surfing in the evening.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)